Photographed by Barry Wetcher © Warner Bros.

By Tim Pelan

As far back as I can remember, director Martin Scorsese has been synonymous with wiseguys, mooks, goombahs, and spin-on-a-dime funny-how guys delivering a gut punch to the senses, all choreographed to a wowser wall of sound. Young pretenders like Quentin Tarantino and Edgar Wright certainly learnt how to make up a killer score not, conversely, on the streets, but at the church of St Martin. The rest is bullshit (but that’s another film). We’re here to talk about Goodfellas (1990), surely his most guilty thrill ride until The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), the white-collar larcenous flip side to the saga of Henry Hill, an initial outsider like the young, asthmatic Scorsese in Little Italy, who finds an in to the neighbourhood mobster way of life. Scorsese indulges in the seductive surface appeal of these dodgy foot soldiers, gradually peeling away the layers like finely chopped garlic to reveal the lousy, grifting, desperate and moral hollow at the centre. Critic David Thomson in The Big Screen: The Story of the Movies and What They Did to Us says, “Scorsese looks at clothes, decor and male gesture like a cobra scrutinizing a charmer. You feel he is realizing his own desires, or bringing them to life: he hungers for his own imagery as a fantasy made vivid.” The director himself reflected later to Richard Schickel that he saw the film a little differently. “I wanted to seduce everybody into the movie and into the style. And then just take them apart with it. I guess I wanted a kind of angry gesture.” A kind of magic carpet ride rug-pull too, the Seinfeld of gangster films, with “no hugging, no learning.” The only regret is in getting pinched.

Goodfellas is based on the true-life story of Henry Hill (played by Ray Liotta), a low-level gangster from boyhood to manhood stretching through the 1960s and 1970s, turned FBI informer, as related by him to crime reporter Nicholas Pileggi in his book, Wise Guy: Life in a Mafia Family. The author collaborated with Scorsese on the screenplay. The Irish American Hill’s crimes escalated from stealing cigarettes for local Italian American kingpin Paulie (Paul Sorvino) to larger scale robberies, selling stolen goods, loan sharking, hijacking, arson and eventual drug dealing, which would be his downfall. It’s funny how (!) the mob is so squeamish about drug dealing. Hill’s secrecy and sampling of his product cause severe paranoia and sloppiness, leading to his own downfall and actual salvation, although he can’t see it that way. Parallel and complicit to all this is his tumultuous life with his wife Karen (Lorraine Bracco) for whom he converts from Catholicism to Judaism. Not to mention several mistresses along the way.

Research hound Robert De Niro, who played Jimmy “The Gent” Conway, mentor and murderous friend to Hill, kept in contact with the real deal. “I would call Henry Hill every couple of days and check with him. I would just say, ‘I need to talk to Henry,’ and they would find him wherever he was. He was in a witness protection program at the time.” Goodfellas really opened the lid on the garrulous gangsters we’re familiar with today, like The Sopranos, many of that shows cast members having appeared in the film also. The Godfather was stately, secretive, a closed house. Here, it’s open house, where it’s all fun and games in wild nights out or after-hours card games until somebody loses an eye, or an arm. Or “Here’s a wing!” as Hill’s Italian-born hair-trigger friend Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci) quips, when the trio of brothers in arms are burying Billy Batts (Frank Vincent) who’s ragging of Tommy (“Now go home and get your fuckin’ shine box!”) went a little too far. An anthropological Goodlife through a lens.

Here are a couple of quotes from Scorsese that sum up both the style and the message of the film:

“I was interested in breaking up all the traditional ways of shooting the picture. A guy comes in, sits down, exposition is given. So the hell with the exposition—do it on the voiceover, if need be at all. And then just jump the scene together. Not by chance. The shots are designed so that I know where the cut’s going to be. The action is pulled out of the middle of the scene, but I know where I’m going to cut it so that it makes an interesting cut… In this film, actually the style gave me the sense of going on a ride, some sort of crazed amusement-park ride, going through the Underworld, in a way.”

And how he uses Hill “as a mirror of American Society”:

“Yeah, the lifestyle reflects the times. In the early sixties, the camera comes up on Henry and he’s waiting outside the diner and he’s got this silk suit on and he hears ‘Stardust.’ And he’s young and he’s looking like all the hope in the world ready for him and he’s going to conquer the world. And then you just take it through America—the end of the sixties, the seventies, and finally into the end of the seventies with the disillusionment and the state of the country that we’re in now. I think his journey reflects that. That wasn’t planned. But there’s something about the moment when his wife says, ‘Hide that cross,’ and the next thing you know, he’s getting married in a Jewish ceremony, and wearing a Star of David and a cross—it doesn’t make any difference. Although I didn’t want to make it heavy in the picture, the idea is that if you live for a certain kind of value, at a certain point in life you’re going to come smack up against a brick wall. Not only Henry living as a gangster: in my feeling, I guess it’s the old materialism versus a spiritual life.”

Scorsese uses several long takes, holding on the action playing in background, subtext, and written across faces. The infamous “Funny how?” exchange was first improvised, then tightly scripted, drawn from a childhood recollection of Joe Pesci’s. Scorsese said “it was really finally done in the cutting with two cameras. Very, very carefully composed. Who’s in the frame behind them. To the point where we didn’t have to compromise lighting and positions of the other actors, because it’s even more important who’s around them hearing this.”

The most astonishing long take, or sequence shot, as it conveys everything the film needs to tell you about Henry’s access and power at an early point in the movie, is his and Karen’s first real date, as he sweeps her through the side entrance, back corridors and kitchen of the Copacabana club to the dining area. Henry tips and jokes with staff, guiding Karen through the kitchen. He is focused, in control of the moment, the camera gliding along in his wake. A waiter whisks a white-clothed table in front of them and places it right in front of the stage, Henry and Karen settling back into likewise magically appearing chairs (“Hey, how come we can’t get a table?” someone is overheard off camera). At the time, this was the longest ever Steadicam shot in a film, at two minutes, 59 seconds, scored to the evocative Then He Kissed Me by The Crystals. It reflects Henry’s acceptance into that world, his seduction of the innocent too—“What do you do?” Karen wonders aloud. In actuality there were several strata to the seating arrangements—the footsoldiers like Henry sat in the lower area by the stage, the bosses up by the rail. Each family sat in their own designated areas. “The camera just glided through this world,” Scorsese reflected. “All the doors opened to him. Everything just slipped away, it was like heaven. Then to emerge like a king and queen—this is the highest he could aspire to.”

The Copa shot was blocked, lit and filmed in half a day, nailed on the eighth take. Steadicam operator Larry McConkey on the process, via Filmmaker Magazine:

“We did our first walkthrough in the late afternoon—the idea was that we would shoot it at night. Lorraine Bracco and Ray Liotta were there, and Marty said that he wanted it to start with this big close-up of the tip being given to somebody to watch Ray’s car, and then we would walk and follow them. So we walked across the street, went down the stairs (of the Copa’s back entrance), around the corner and down a long hallway. Now, Marty may have just thought that he would have voiceover overtop of the shot, but I was kind of looking at my watch and thinking, ‘This is already the worst case of shoe leather in the history of cinema. There’s no way this will ever work.’ We got to the kitchen and Michael Ballhaus said, ‘Marty, we have to go into the kitchen.’ Marty said, ‘Why would they go into the kitchen?’ And Ballhaus said, ‘Because the light is beautiful.’ ‘OK, we go in the kitchen.’ So we turned the corner and went into the kitchen and then back out the same door. Finally, we get into the club and there’s some dialogue and some action, but I’m thinking the first two minutes of this shot are going to be awful. There’s no way they’ll ever use it. They’re going to cut it to hell.

There are technical problems when you’re trying to do an uncut shot. You want the wide and you want the tight in the same shot, but how do you connect the two? Do you just wait while the camera trundles in? You can’t do that. So we essentially had to invent a way to edit it in the shot. I had to be wide to follow (Ray and Lorraine) down the stairs, because otherwise it would be a shot of the tops of their heads, but when they got to the bottom of the stairs they turned a corner and they would disappear if I didn’t catch up to them. So I said, ‘Ray, we have to figure out a way for you to stall at the bottom of the stairs so I can catch up to you.’ Joe Reidy said, ‘We have a lot of extras so we can have a doorman and Ray could talk to him.’ Then someone came up with the idea ‘You know what, Ray should give him a tip.’ Now we’re echoing a theme that’s built into the character and built into the movie. Then walking down the hallway I said, ‘Ray, I really want to see your face now. So we’ve got to figure out a reason for you to turn around.’ He said, ‘Well, I can talk to somebody else in the hall.’ So we brought in a couple who were making out and Ray would turn and say, ‘Every time, you two.’ So we structured events within the shot that covered the limitations of not being able to cut in order to give it pace and timing. What I didn’t expect, and what I only figured out later, was that all those (interactions) ended up being the heart and soul of the shot. Because Ray incorporated his character into those moments, those moments actually became what the shot was about instead of being tricks or being artifices.”

Another sequence shot shortly after this one during Henry and Karen’s courtship further illuminates Henry’s character, and her acceptance of it. She calls him in tears, after being manhandled out on a drive by the young guy from across the street. Henry picks her up and takes her home, checks if she’s okay, tells her to go inside, all the while eyeballing the preppy prick and his friends in their driveway around a red sports car. There’s no music this time, just the diegetic suburban soundscape of barking dogs, birds and sprinklers. Henry, sporting a tan leather jacket that practically screams “hood” this time around does most definitely not belong in this world, as he stalks wordlessly across the street, the camera in front of his approaching menace, then swiveling to take in what follows—he pistol-whips the arrogant kid in an unflinching intrusion of primal pummeling. He warns the guy if he ever touches her again he’s dead, then stalks back across the street, teeth still bared, and tells Karen to hide the bloodied gun. Her voice over is the kicker: “I know there are women, like my best friends, who would have gotten out of there the minute their boyfriend gave them a gun to hide. But I didn’t. I gotta admit the truth: it turned me on.”

Scorsese had invaluable collaborators on Goodfellas—stalwart editor Thelma Schoonmaker; the gorgeous cinematography of Michael Ballhaus; and the production design of Kristi Zea. Not to mention the astounding era-straddling music selection, from do-wop numbers to outstanding paranoia “day in the life” selection Jump Into The Fire by Harry Nilsson. It plays as Henry juggles a (real, flesh and blood) family dinner preparation, leaving his kid brother to stir the sauce while he tries to make a gun deal and deliver drugs, his coked-up, pasty, red-eyed visage craning through the windscreen at that friggin’ helicopter that’s right on his ass. And the Layla (Piano Exit)-scored montage as Jimmy, deep in his own paranoiac greed and security-minded ruthlessness, has everyone involved in the Lufthansa heist systematically offed, their bodies turning up as a sad ignominious refrain to the music beats—Scorsese had the number played live on set. Remember that David Thomson quote at the top of the essay? De Niro’s Jimmy, when he first contemplates this path, is “like a cobra scrutinizing a charmer,” as the camera closes in on him at the bar, ruminating. He even considers later offing Karen, leading her out the back, down to some alley to pick up some goods. Wisely, she gets the jitters and bolts. How in the hell, when the film is this deep in the filth, can it be said to glamorize crime? Mind you, Henry is initially prepared to keep schtum over Jimmy’s purge. Although he was complicit in disposing of Billy Batts, a made guy. When revenge comes knocking for Tommy, there’s not a damn thing he or Jimmy can do about it. That’s a line crossed too far.

Henry upends Jimmy’s advice (“Never rat on your friends and always keep your mouth shut”) to literally save his own skin. “I think Henry realizes the horror he’s brought upon himself, how they’re all living, and it’s way too late. The only thing to do is get out of it. And how can you get out?” Scorsese reflected. By turning everyone in and becoming another nobody “in a neighborhood full of nobodies.” That startling breaking of the fourth wall when Henry steps off the witness stand and addresses us? There’s no real remorse there, only relief (modestly perhaps, Scorsese says he couldn’t think of any other way to end it). As Nev Pierce recalls in his Empire Movie Masterpieces essay, “’We were treated like movie stars with muscle,’ he (Henry) says fondly. ‘Today, everything is different. There’s no action. I have to wait around like everyone else…’ Caught between suburbia and Satan: anonymity and gory glory. Either way, he’s lost.”

Tim Pelan was born in 1968, the year of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (possibly his favorite film), ‘Planet of the Apes,’ ‘The Night of the Living Dead’ and ‘Barbarella.’ That also made him the perfect age for when ‘Star Wars’ came out. Some would say this explains a lot. Read more »

GETTING MADE: THE MAKING OF ‘GOODFELLAS’

Getting Made: The Making of Goodfellas is a fascinating inside look at the making of a masterpiece.

A COMPLETE ORAL HISTORY

It’s hard to imagine that the obsessive and frenetic Martin Scorsese ever endured blue periods in his career, but twenty years ago, he was going through one. On the eve of the premiere of his new movie, Goodfellas, he was still recovering from the protests, denunciations, and death threats that had accompanied The Last Temptation of Christ. But Goodfellas—based on Wiseguy, a nonfiction best seller by legendary crime reporter Nicholas Pileggi—would restore Scorsese’s place in American film, and then some. To mark the film’s anniversary, GQ interviewed nearly sixty members of the cast and crew, along with some noteworthy admirers of the picture, to revisit the making of one of the most endlessly rewatchable American movies ever made.—Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas: A Complete Oral History

Martin Scorsese interviewed by Gavin Smith, Film Comment, September/October 1990.

What was it that drew you to the Goodfellas material?

I read a review of the book; basically it said, “This is really the way it must he.” So I got the book in galleys and started really enjoying it because of the free-flowing style, the way Henry Hill spoke, and the wonderful arrogance of it. And I said, oh, it would make a fascinating film if you just make it what it is—literally as close to the truth as a fiction film, a dramatization, could get. No sense to try to whitewash, [to elicit] great sympathy for the characters in a phony way. If you happen to feel something for the character Pesci plays, after all he does in the film, and if you feel something for him when he’s eliminated, then that’s interesting to me. That’s basically it. There was no sense making this film [any other way].You say dramatization and fiction. What kind of a film do you see this as being?

I was hoping it was a documentary. [Laughs]. Really, no kidding. Like a staged documentary, the spirit of a documentary. As if you had a 16mm camera with these guys for 20, 25 years; what you’d pick up. I can’t say it’s “like” any other film, but in my mind it [Has] the freedom of a documentary, where you can mention 25 people’s names at one point and 23 of them the audience will not have heard of before and won’t hear of again, but it doesn’t matter. It’s the familiarity of the way people speak. Even at the end when Ray Liotta says over the freezeframe on his face, “Jimmy never asked me to go and whack somebody before. But now lie’s asking me to go down and do a hit with Anthony in Florida.” Who’s Anthony? It’s a mosaic, a tapestry, where faces keep coming in and out. Johnny Dio, played by Frank Pellegrino, you only see in the Fifties, and then in the Sixties you don’t see him, but he shows up in the jail sequence. He may have done something else for five or six years and come back. It’s the way they live.How have your feelings about this world changed since Mean Streets?

Well, Mean Streets is much closer to home in terms of a real story, somewhat fictionalized, about events that occurred to me and some of my old friends. [Goodfellas] has really nothing to do with people I knew then. It doesn’t take place in Manhattan, it’s only in the boroughs, so it’s a very different world—although it’s all interrelated. But the spirit of it, again, the attitudes. The morality—you know, there’s none, there’s none. Completely amoral. It’s just wonderful. If you’re a young person, 8 or 9, and these people treat you a certain way because you’re living around them, and then as you get to be a teenager and you get a little older, you begin to realize what they did and what they still do—you still have those first feelings for them as people, you know. So, it kind of raises a moral question and a kind of moral friction in me. That was what I wanted to get on the screen.

How did you feel about Married to the Mob, which satirized the Mafia lifestyle?

I like Jonathan Demme’s movies. In fact, I have the same production designer, Kristi Zea. But, well, it’s a satire—it’s just too many plastic seat-covers. And yet, if you go to my mother’s apartment, you’ll see not only the plastic seatcovers on the couch but on the coffee table as well. So where’s the line of the truth? I don’t know. In the spirit of Demme’s work I enjoyed it. But as far as an Italian-American thing, it’s really like a cartoon. When he starts with “Mambo Italia no,” Rosemary Clooney, I’m already cringing because I’m Italian-American, and certain songs we’d like to forget! So I told Jonathan he had some nerve using that, I said only Italians could use “Mambo Italiano” and get away with it. There might be some knocks at his door [Laughs].Do Goodfellas and Mean Streets serve as an antidote to The Godfather’s mythic version of the Mafia?

Yes, yeah, absolutely. Mean Streets, of course, was something I was just burning to do for a number of years. [By the time I did it,] The Godfather had already come out. But I said, it doesn’t matter, because this one is really, to use the word loosely, anthropology—that idea of how people live, what they ate, how they dressed. Mean Streets has that quality—a quote “real” unquote side of it. Goodfellas more so. Especially in terms of attitude. Don’t give a damn about anything, especially when they’re having a good time and making a lot of money. They don’t care about their wives, their kids, anything.The Godfather is such an overpowering film that it shapes everybody’s perception of the Mafia—including people in the Mafia.

Oh, sure. I prefer Godfather II to Godfather I. I’ve always said it’s like epic poetry, like Morte d’Arthur. My stuff is like some guy on the street-corner talking.

In Goodfellas we see a great deal of behavior, bat yon withhold psychological insight.

Basically I was interested in what they do. And, you know, they don’t think about it a lot. They don’t sit around and ponder about [laughs]. “Gee, what are we doing here?” The answer is to eat a lot and make a lot of money and do the least amount of work as possible for it. I was trying to make it as practical and primitive as possible. Just straight ahead. Want. Take. Simple. I’m more concerned with showing a lifestyle and using Henry Hill (Ray Liotta] as basically a guide through it.You said you see this as a tragic story.

I do, but you have a lot of the guys, like [real-life U.S. attorney] Ed McDonald in the film or Ed Hayes [a real defense attorney], who plays one of the defense attorneys, they’ll say, “These guys are animals and that’s life,” and maybe not care about them. Henry took Paulie [Paul Sorvino] as sort of a second father; he just idolized these guys and wanted to be a part of it. And that’s what makes the turnaround at the end so interesting and so tragic, for me.In Scorsese on Scorsese you said that, growing up, you felt being a rat was the worst thing you could be. How do you feel about Henry and what he did?

That’s a hard one. Maybe on one level, the tragedy is in the shots of Henry on the stand: “Will you point him out to me, please?” And you see him look kind of sheepish, and he points to Bob De Niro playing Jimmy Conway. And the camera moves in on Conway. Maybe that’s the tragedy—what he had to do to survive, to enable his family to survive.

This is “Henry Hill” as opposed to Henry Hill—purely an imaginative version of this guy?

Yes. Based on what he said in the book and based on what [co-writer] Nick [Pileggi] told me. I never spoke to Henry Hill. Towards the end of the film I spoke to him on the phone once. He thanked me about something. It was just less than 30 seconds on the phone.You use him as a mirror of American society.

Yeah, the lifestyle reflects the times. In the early Sixties, the camera comes up on Henry and he’s waiting outside the diner and he’s got this silk suit on and he hears “Stardust.” And he’s young and he’s looking like all the hope in the world ready for him and he’s going to conquer the world. And then you just take it through America—the end of the Sixties, the Seventies, and finally into the end of the Seventies with the disillusionment and the state of the country that we’re in now. I think his journey reflects that. That wasn’t planned. But there’s something about the moment when his wife says, “Hide that cross,” and the next thing you know, he’s getting married in a Jewish ceremony, and wearing a Star of David and a cross—it doesn’t make any difference. Although I didn’t want to make it heavy in the picture, the idea is that if you live for a certain kind of value, at a certain point in life you’re going to come smack up against a brick wall. Not only Henry living as a gangster: in my feeling, I guess it’s the old materialism versus a spiritual life.Goodfellas is like a history of postwar American consumer culture, the evolution of cultural style. The nai vete and romanticism of the Fifties… There’s a kind of innocent mischief mid charm to the worldliness. But then at a certain point it becomes corrupt.

It corrupts and degenerates. Even to the point (that) some of the music degenerates in itself. You have “Unchained Melody” being sung in a decadent way, like the ultimate doo-wop—but not black, it’s Italian doowop. It’s on the soundtrack after Stacks gets killed and Henry comes running into the bar. Bob tells him, “Come on, let’s drink up, it’s a celebration,” and Tommy says, “Don’t worry about anything. Going to make me.” And over that you hear this incredible doo-wop going on, and it’s sort of like even the music becomes decadent in a way from the pure Drifters, Clyde McPhatter singing “Bells of St. Mary’s,” to Vito and the Salutations. And I like the Vito and the Salutations version of “Unchained Melody.” Alex North wrote it along with somebody else—it was from this movie made in the early Fifties called Unchained. And it’s unrecognizable. It’s so crazy and I enjoy it. I guess I admire the purity of the early times and… Not that I admire it, but I’m a part of the decadence of what happened in the Seventies and the Eighties.

Pop music is usually used in films, at least on one level, to cue the audience to what era it is.

Oh, no, no, forget that, no. In Mean Streets there’s a lot of stuff that comes from the Forties. The thing is, believe me, a lot of these places you had jukeboxes and, when The Beatles came in, you still had Benny Goodman, some old Italian stuff, Jerry Vale, Tony Bennett, doo-wop, early rock ‘n’ roll, black and Italian… There’s a guy who comes around and puts the latest hits in. [But] when you hang out in a place, when you are part of a group, new records come in but [people] request older ones. And they stay. If one of the guys leaves or somebody gets killed, some of his favorite music [nobody else] wants to listen to, they throw it away. But basically there are certain records that guys like and it’s there. Anything goes, anything goes.Why Sid Vicious doing “My Way” at the end?

Oh, it’s pretty obvious, it may be even too obvious. It’s period, but also it’s Paul Anka and of course Sinatra—although there’s no Sinatra in the film. But “My Way” is an anthem. I like Sid Vicious’ version because it twists it, and his whole life and death was a kind of slap in the face of the whole system, the whole point of existence in a way. And that’s what fascinating to me—because eventually, yeah, they all did it their way. [Laughs] Because we did it our way, you know.Goodfellas’ vision of rock ‘n’ roll style colliding with a fetishized gangster attitude made me think of Nic Roeg’s Performance, which was about the dark side of the Sixties too.

Oh I like Performance, yeah. I never quite understood it, because I didn’t understand any of the drug culture at that time. But I liked the picture. I love the music and I love Jagger in it and James Fox—terrific. That’s one of the reasons I used the Ry Cooder [song] “Memo to Turner”—the part where Jimmy says, “Now, stop taking those fucking drugs, they’re making your mind into mush.” He slams the door. He puts the guns in the trunk and all of a sudden you hear the beginning of this incredible slide guitar coming in. It’s Ry Cooder. And I couldn’t use the rest of it because the scene goes too quick. The Seventies drug thing was important because I wanted to get the impression of that craziness. Especially that last day, he starts at six in the morning. The first thing he does is gets the guns, takes a hit of coke, gets in the car. I mean, you’re already wired, you’re wired for the day. And his day is like crazy. Everything is at the same importance. The sauce is just as important as the guns, is as important as Jimmy, the drugs, the helicopter. The idea was to stylistically try to give the impression—people watching the film who have taken drugs will recognize it—of the anxiety and the thought processes. And the way the mind races when you’re taking drugs, really doing it as a lifestyle.

The film’s first section presents a kind of idealized underworld with its own warmth and honor-among-thieves code. This gradually falls away, reflected in the characters of Tommy and Jimmy.

True, true. But Jimmy Conway was not Mafia. The idea was, you signed on for that life, you may have to exit that life in an unnatural way, and they knew that. I’m not saying, oh, those were the good old days. In a funny way [laughs]—not that funny—but in a way there’s a breakdown of discipline, of whatever moral code those guys had in the Fifties and Sixties. I think now with drugs being the big money and gangsters killing people in the government in Colombia, the Mafia is nothing. They’ll always be around, there’ll always be the organized-crime idea. But in terms of the old, almost romantic image of it typified by the Godfather films, that’s gone.The Seventies sequence is about losing control, about disintegration.

Totally. Henry disintegrates with drugs. With Jimmy Conway, the disintegration is on a more lethal level, the elimination of [everybody else]. Earlier there’s so many shots of people playing cards and at christenings and weddings, all at the same table. If you look at the wedding, the camera goes around the table and all the people at that table are killed by Jimmy later on.Unlike all your other protagonists, Henry seems secure in his identity. What is his journey, from your point of view?

You know, I don’t know. I don’t mean to be silly; I guess I should have an answer for that. Maybe in the way he feels through his voiceover in the beginning of the film about being respected. I think it’s really more about Henry not having to wait in line to get bread for his mother. It’s that simple. And to be a confidante of people so powerful, who, to a child’s mind, didn’t have to worry about parking by a hydrant. It’s the American Dream.

Once he has this status lifestyle, what’s at stake for him?

Things happen so fast, so quick and heavy in their lifestyle, they don’t think of that. Joe Pesci pointed out that you have literally a life expectancy—the idea of a cycle that it takes for a guy to be in the prime of being of wiseguy—the prime period is like maybe eight or nine years, at the end of which, just by the law of averages, you’re either going to get killed or most likely go to jail. And then you begin the long thing with going back and forth from jail to home, jail to home. It begins to wear you down until only the strongest survive. I think Henry realizes the horror he’s brought upon himself, how they’re all living, and it’s way too late. The only thing to do is get out of it. And how can you get out?He remains an enigma—untainted by what he’s done and at the end achieving a kind of grace as just a regular guy like everybody else. What were you trying to do with the ending?

It’s just very simply that’s the way the book ended and I liked what he said, I liked his attitude: “Gee, there’s no more fun.” [Laughs] Now, you can take that any way you want. I think the audience should get angry with him. I would hope they would be. And maybe angry with the system that allows it —this is so complex. Everything is worked out together with these guys and with the law and with the Justice Department. It’ll be phony if he felt badly about what he did. The irony of it at the end I kind of think is very funny.Why do you have him addressing the camera at the end?

Couldn’t think of any other thing to do, really. Just, you know, got to end the picture. Seriously.

How did you conceptualize the film stylistically? Did you break the film down into sequences?

Yeah, as much as possible. Everything was pretty much storyboarded, if not on paper, in notes. These days I don’t actually draw each picture. But I usually put notes on the sides of the script, how the camera should move. I wanted lots of movement and I wanted it to be throughout the whole picture, and I wanted the style to kind of break down by the end, so that by his last day as a wiseguy, it’s as if the whole picture would be out of control, give the impression he’s just going to spin off the edge and fly out. And then stop for the last reel and a half. The idea was to get as much movement as possible—even more than usual. And a very speeded, frenetic quality to most of it in terms of getting as much information to the audience—overwhelming them, I had hoped—with images and information. There’s a lot of stuff in the frames. Because it’s so rich. The lifestyle is so rich—I have a love-hate thing with that lifestyle.I don’t think I’ve ever seen freeze frames used in such a dramatic way—freezing a moment and bringing the narrative to a halt.

That comes from documentaries. Images would stop; a point was being made in his life. Everybody has to take a beating sometime, BANG: freeze and then go back with the whipping. What are you dealing with there? Are you dealing with the father abusing Henry—you know, the usual story of, My father beat me, that’s why I’m bad. Not necessarily. You’re just saying, “Listen, I take a beating, that’s all, fine.” The next thing, the explosion and the freezeframe, Henry frozen against it—it’s hellish, a person in flames, in hell. And he says, “They did it out of respect.” It’s very important where the freezeframes are in that opening sequence. Certain things are embedded in the skull when you’re a kid. The freezeframes are basically all Truffaut. [The style] comes from the first two or three minutes of Jules and Jim. The Truffaut and Godard techniques from the early Sixties that have stayed in my mind—what I loved about them was that narrative was not that important: “Listen, this is what we’re going to do right now and I’ll he right back. Oh, that guy, by the way, he got killed. We’ll see you later.” Ernie Kovacs was that way in the Fifties in TV. I learned a lot from watching him destroy beautifully the form of what you were used to thinking was the television comedy show. He would stop and talk to the camera and do strange things; it was totally surreal. Maybe if I were of a different generation I would say Keaton. But I didn’t grow up with Keaton, I grew up with early TV.Or if you’re my generation it would be Pee Wee’s Playhouse.

Yeah, again, breaking up a narrative—just opens up a refrigerator, there’s a whole show inside, and closes the door. That’s great. I love Pee Wee Herman. I tape the show. We had them sent to Morocco when we were doing Last Temptation; on Sundays we’d watch it on PAL system. Yeah. [Laughs]

Goodfellas uses time deletions during many scenes: you see someone standing by the door, then they’re suddenly in the chair, then—

It’s the way things go. They’ve got to move fast. I was interested in breaking up all the traditional ways of shooting the picture. A guy comes in, sits down, exposition is given. So the hell with the exposition—do it on the voiceover, if need be at all. And then just jump the scene together. Not by chance. The shots are designed so that I know where the cut’s going to be. The action is pulled out of the middle of the scene, but I know where I’m going to cut it so that it makes an interesting cut. And I always loved those jump cuts in the early French films, in Bertolucci’s Before the Revolution. Compressing time. I get very bored shooting scenes that are traditional scenes. In this film, actually the style gave me the sense of going on a ride, some sort of crazed amusement-park ride, going through the Underworld, in a way. Take a look at this, and you pan over real fast and, you know, it kind of lends itself to the impression of it not being perfect—which is really what I wanted. That scene near the end, Ed McDonald talking to [the Hills]—I like that, [it’s as if the movie] kind of stops, it gets cold and they’re in this terrifying office. He’s wearing a terrifying tie—it’s the law and you’re stuck. And they’re on the couch and he’s in a chair and that’s the end of the road. That’s scary.When you’re shooting and editing, how do you determine how much the audience can take in terms of information, shot length, number of cuts, etc.? Over the past decade our nervous systems have developed a much greater tolerance of sensory overload.

I guess the main thing that’s happened in the past ten years is that the scenes have to be quicker and shorter. Something like The Last Emperor, they accept in terms of an epic style. But this is sort of my version of MTV, this picture. But even that’s old-fashioned.Is there a line you won’t cross in terms of editing speed, how fast to play scenes?

The last picture I made was Life Lessons in New York Stories. And that’s pretty much the right level. Goodfellas lends itself to a very fast-paced treatment. But I think where I’m at is really more the New York Stories section. Not Last Temptation. Last Temptation, things were longer and slower there because, well, of a certain affection for the story and for the things that make up that story. And the sense of being almost stoned by the desert in a way, being there and making things go slower; a whole different, centuries-earlier way of living. New York Stories had, I think, maybe a balance between the two. The scenes went pretty crisp, pretty quickly. There were some montage sequences. But still I’d like to sustain [the moments]. In Goodfellas, that whole sequence I really developed with the actors, Joe Pesci’s story and Ray responding to him, it’s a very long sequence. We let everything play out. And I kept adding setups to let the whole moment play out. But if what the actors were doing was truthful or enjoyable enough, you can get away with it.

The “What’s so funny about me?” scene in the restaurant between Liotta and Pesci was improvised?

Totally improv—yeah. It’s based on something that happened to Joe. He got out of it the same way—by taking the chance and saying, “Oh, come on, knock it off.” The gentleman who was threatening him was a friend, (but) a dangerous person. And Joe’s in a bad state either way. If he doesn’t try laughing about it, he’s going to be killed; if he tries laughing about it and the guy doesn’t think it’s funny, he’s going to be killed. Either way he’s got nothing to lose. You see, things like that, they could turn on a dime, those situations. And it’s just really scary. Joe said, “Could I please do that?” I said, “Absolutely, let’s have some fun.” And we improvised, wrote it down, and they memorized the lines. But it was really finally done in the cutting with two cameras. Very, very carefully composed. Who’s in the frame behind them. To the point where we didn’t have to compromise lighting and positions of the other actors, because it’s even more important who’s around them hearing this.What about the continuation of the scene with the restaurant owner asking for the money?

Oh, that’s all playing around, yeah. That kind of dialogue you can’t really write. And the addition of breaking the bottle over Tony Harrow’s head was thought of by Joe at lunchtime. I got mad at him. I said, “How could you—why now, at lunch? Now we’ve got to stop the shooting. We’ve got to go down and get fake bottles.” He said, “Well, couldn’t we maybe do it with a real bottle?” “No.” “Well, maybe we could throw it at him.” “No, no, that’s not as good.” “How about a lamp? Let’s hit him with a lamp.” So we tried hitting him with different things. It was actually one of the funniest days we ever had. Everybody came to visit that day. And I don’t like visitors on the set, but that was a perfect time to have them visit because most of the laughter on the tracks that you hear is people from behind the camera, me and a lot of Warners executives who showed up. The real improvs were done with Joe and Frank Severa, who played Carbone, who kept mumbling in Sicilian all the time. And they kept arguing with each other. Like the coffee pot: “That’s a joke. Put it down. What, are you going to take the pot?”—he was walking out with the pot. It’s more like telling him, even as an actor, “Are you out of your mind? Where are you going with the coffee? We don’t do that.” Another killing, Joe says, “Come on, we have to go chop him up.” And Frank starts to get out of the car. And Joe says, “Where are you going, you dizzy motherfucker? What’s the matter with you? We’re going to go chop him up here.” Frank’s impulse was to get out of the car. So Joe just grabbed him and said, “What are you doing?” They improvised.Did you ever get feedback from the underworld after Mean Streets?

From my old friends. A lot of the people that the film is about are not Mafia. Nick mentioned that the real-life Paulie Cicero never went to the movies, never went out, didn’t have telephones, you know. So one night the guys wanted to see this one particular movie, and they just grabbed him and threw him in the car and took him to see the film. It was Mean Streets. They loved it. So that was like the highest compliment, because I really try to be accurate about attitude and about way of life.

THE ‘GOODFELLAS’ COPACABANA TRACKING SHOT

The legendary Steadicam shot in Goodfellas through the nightclub kitchen was a happy accident—Scorsese had been denied permission to go in the front way and had to improvise an alternative. Here’s a commentary by D.P. Michael Ballhaus, co-screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi and Scorsese himself. Goodfellas is what makes cinema so great—the ABCs of adept filmmaking, the sheer power of storytelling, the unique magic that makes you fall in love with characters that are far from deserving such affection.

“We did our first walkthrough in the late afternoon—the idea was that we would shoot it at night. Lorraine Bracco and Ray Liotta were there, and Marty said that he wanted it to start with this big close-up of the tip being given to somebody to watch Ray’s car, and then we would walk and follow them. So we walked across the street, went down the stairs (of the Copa’s back entrance), around the corner and down a long hallway. Now, Marty may have just thought that he would have voiceover overtop of the shot, but I was kind of looking at my watch and thinking, ‘This is already the worst case of shoe leather in the history of cinema. There’s no way this will ever work.’ We got to the kitchen and Michael Ballhaus said, ‘Marty, we have to go into the kitchen.’ Marty said, ‘Why would they go into the kitchen?’ And Ballhaus said, ‘Because the light is beautiful.’ ‘OK, we go in the kitchen.’ So we turned the corner and went into the kitchen and then back out the same door. Finally, we get into the club and there’s some dialogue and some action, but I’m thinking the first two minutes of this shot are going to be awful. There’s no way they’ll ever use it. They’re going to cut it to hell. Marty looked at me (for my reaction to the rehearsal) and I said, ‘Yeah sure.’ And he said, ‘Okay, I’ll be back in a couple of hours.’ Ray saw the panic in my eyes and asked if I wanted him to stay and help me work the shot out. So Ray and the First Assistant Director Joe Reidy stayed and we started to walk through the shot again.” —Steadicam operator Larry McConkey on filming the Goodfellas Copacabana tracking shot and the early days of Steadicam

MICHAEL BALLHAUS, ASC, BVK (1935-2017)

“How many filmmakers can say that they helped revive a young Martin Scorsese’s career? German cinematographer, Michael Ballhaus, was among those few; his talents helped inject Scorsese’s early work with the vigor and energy we’ve come to know so well. But even before working with Scorsese on films like Goodfellas and After Hours, Ballhaus had already established himself as a gifted and well-respected director of photography through his many collaborations with the renowned German director, Rainer Werner Fassbinder. But what is it about Ballhaus’s style that’s so iconic? Perhaps the biggest common denominator is that he defied definition. He adapted his vision to each film’s unique circumstances, generating one-of-a-kind imagery each time. One touch he is particularly known for is his camera movement: Ballhaus’s camera was always in motion, and each movement told its own story. In the newest installment of our series, Language of the Image, we honor those stories and remember the work of the late Michael Ballhaus, a cinematic presence who will be sorely missed.” —Fandor

THELMA SCHOONMAKER

“And, you know, the wonderful thing is that my husband got that movie made, because Marty couldn’t get it made. All the studios kept saying to him, ‘Take out the drugs.’ And he said ‘The drugs are the story of the movie, we can’t take it out.’ He tried three times to sell it, and he was in despair. I came home to my husband and I said ‘Marty’s really having trouble,’ and he said, ‘read me the script’—because my husband, he could see, but his eyes had degenerated which meant he was not able to read. So I read him the script. He said, ‘Get Marty on the phone,’ and I did—it was a Sunday, the one day I got off!—and he said, ‘Marty, you have to make this movie. This is the most brilliant script I’ve read in 20 years, you have to make this movie.’ Marty went in one more time and he got it made. My husband died before he saw it, but he got it made, and it saved me. Because when my husband died, I didn’t want to live anymore, and I had to come back to Goodfellas. Marty shut the movie down, because he loved Michael so much, to let me take him back to England. I didn’t want him to die in America. He waited two months, until Michael died, and he shut the movie down, the editing, and then when I came back, I knew if I didn’t go back and help Marty, my husband would kill me. So, I went back and it pulled me out of my grief, and so it’s a film that has much resonance, you know? It’s just a shame that Michael never saw it, he would have loved it.” —Thelma Schoonmaker

Martin Scorsese and Thelma Schoonmaker editing Goodfellas.

Thelma Schoonmaker, in a remarkable 17-minute interview from 1993.

“IT IS ONE OF THE BEST CONSTRUCTED

SCRIPTS THAT I HAVE EVER READ”

“It was in 1975 that Martin Scorsese finally met his idol, Michael Powell, and embarked upon a fifteen year friendship that would see Powell—one half of The Archers and the renowned British filmmaker behind such movies as The Red Shoes, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, and, most controversially, Peeping Tom—repeatedly offering invaluable advice and feedback to the American director. A perfect example: In 1988, after reading a new script of Scorsese’s entitled Wise Guys, Powell sent his friend the following enthusiastic letter and declared it ‘one of the best constructed scripts [he had] ever read.’ That movie’s eventual title was Goodfellas. Powell sadly passed away in February of 1990, just months before the completed film’s theatrical release.” —Shaun Usher, Letters of Note

Screenwriter must-read: Nicholas Pileggi & Martin Scorsese’s screenplay for Goodfellas [PDF1, PDF2]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

According to the real Henry Hill, whose life was the basis for the book and film, Joe Pesci’s portrayal of Tommy DeVito was 90% to 99% accurate, with one notable exception; the real Tommy DeVito was a massively built, strapping man. In a documentary entitled The Real Goodfella, which aired in the UK, Henry Hill claimed that Robert De Niro would phone him seven to eight times a day to discuss certain things about Jimmy’s character, such as how Jimmy would hold his cigarette, etc. After the premiere, Henry Hill went around and revealed his true identity. In response, the government kicked him out of the Federal Witness Protection Program.

Nev Pierce’s fascinating 2010 interview with this controversial and charismatic figure.

Join host Sean O’Connell for a double feature of behind the scenes Goodfellas documentaries: Getting Made: The Making of Goodfellas and Made Men: The Goodfellas Legacy.

“I guess the film I experimented on the most was probably Goodfellas. But then again, I’m not sure I would call that experimenting, as the style was mainly based on Citizen Kane’s ‘March of Time’ sequence and the first few minutes of Truffaut’s Jules and Jim. In the latter film, every frame is just filled with information, beautiful information, and there’s a narration which tells you one thing when, in fact, the image shows you something else… It’s very, very rich, and that sort of richness of detail is what I played with in Goodfellas. So it was nothing new, really. But what was new, I felt, was the exhilaration of the narration juxtaposed to the images to create the emotion of that lifestyle, of being a young gangster.” —Martin Scorsese, Moviemakers’ Master Class: Private Lessons from the World’s Foremost Directors

How the helicopter chase in Goodfellas was made, by Luís Azevedo.

Rare behind the scenes footage of Goodfellas—shot by filming location homeowner, George Sikat, and interview with Joe Pesci.

“MORRIE’S WIGS ARE TESTED AGAINST HURRICANE WINDS”

The ads for Morrie’s Wigs in Goodfellas weren’t directed by Scorsese. In fact, the director tapped Stephen R. Pacca, the owner of a replacement window company, who had created his own line of kitschy ads on a shoestring budget, and had him direct the commercials himself.

“What we all agreed on was that Steve would not only direct it, but he would put everything together. The only things we would provide would be the camera and our Director Of Photography, Michael Ballhaus, to shoot it, but he’d take direction from Steve Pacca. Michael had two assistants, and a sound mixer and boom operator, but again only under Steve’s direction. All of the special effects, all the prop work, all the make-up and wardrobe would be done by Steve Pacca’s group, which were really people who worked in his office or installed the windows. Someone operating a fan? His guy, with a fan that they brought. A normal house fan.” —Morrie’s Wigs: Behind The Curtain

Martin Scorsese delivers the prestigious David Lean film lecture and shares insights into his illustrious career.

MADE MEN: THE STORY OF GOODFELLAS

by Glenn Kenny

Glenn Kenny’s Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas is available in stores and online. Absolutely essential reading! Read an excerpt here. Get your copy here.

Martin Scorsese shares his cinematic inspirations when making his iconic film Goodfellas. Watch the entire interview as part of the 12th annual TCM Classic Film Festival exclusively on HBO Max.

In loving memory of Ray Liotta (December 18, 1954 – May 26, 2022) and Paul Sorvino (April 13, 1939 – July 25, 2022)

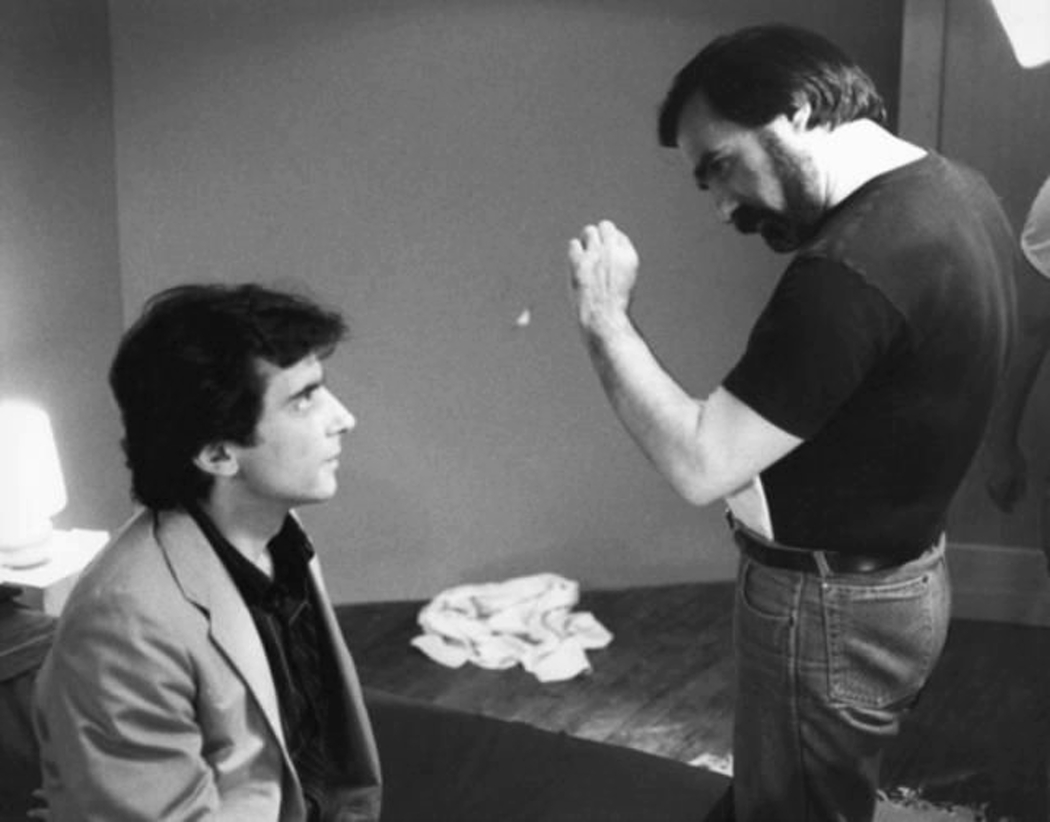

Here are several photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas. Photographed by Barry Wetcher © Warner Bros. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or donate directly below: