Total Recall poster by Kyle Lambert

April 2, 2023

By Tim Pelan

I made the movie in a way that it would be true on both levels, and I spent a lot of time to get that. If you want a scientific explanation, you know, of course, in quantum mechanics there is a very interesting principle, the principle of uncertainty, Heisenberg’s principle. If you have a moving object and if you try to measure the place of the object and the velocity of the object at the same time, the more precisely you measure velocity the less precise place gets. So that’s the principle. That means, of course, that there are different realities possible at the same moment. What I wanted to do in Total Recall is to do a movie where both levels are true. I mean for me, of course, the film anyhow has to do with two realities, one being the reality of going as a secret agent to Mars and discovering that there is a problem, and solving the problem, which is starting the nuclear reactor and helping the guerrillas and destroying Cohaagen. The second level of the movie, of course, is that from the moment that he goes into the Rekall chair till the end it’s a dream, and I tried to make that second level work throughout the whole movie. So there’s the dream level which starts when he gets into the chair and the thing is in his neck, and that would go throughout the whole movie, so in the next scene where they say, “Oh, there’s a problem, there’s a big glitch here,” that would be already the dream, of course. That’s where the dream starts. And the next scene where they are fighting and stuff would be part of his dream, convincing him that it is real, because there is a glitch, but that would be part of the program. It would be built into the program to make him accept the fact that it’s real, but it’s a dream. If you look at the movie, if you haven’t seen it, or for the second time, you’ll see that the whole program that’s set up at the beginning when he goes to the Rekall office and he talks to this guy who sells him the program on Mars, you’ll see that he gets everything that he wants: he gets the trip to Mars, he gets the girl, the exotic girl, he kills the bad guys, and he saves the entire planet. That’s what he does. And that’s basically the dream. Even halfway through the movie, you may remember, this other guy comes in, Dr. Edgemar, and tells him that he’s in a dream, that he’s still in the Rekall chair, and then Arnold says, “If I’m there, I can kill you.” And he puts a gun to his head and the guy says, “Sure, no problem for me, big problem for you, because you will be psychotic from now on because the walls of reality will fall apart. One moment you will be the savior of the rebel cause, the next moment you’ll be Cohaagen’s bosom buddy, but in the end—you will even have these strange fantasies about alien civilizations—but at the end you will be lobotomized.” And then if you see the movie, you realize that all these things happen. I mean he is lobotomized at the end. That’s why at the last shot, when they are so happy and kissing each other, it slowly fades to white, which for me meant, “OK, there he goes. That’s the end—that’s the dream—they lobotomized him.” And all the other things happened—he finds the alien civilization, he rescues the planet, he finds the good girl, he kills the bad guys—but it’s a dream. Now, of course you can see it as a reality, too. So at the end of the movie, going to white means either it’s a happy ending or he loses his brains, which is a probably also a happy ending, I don’t know. That was basically what I wanted: that at the end there would be two possibilities, and they would be both true. For me they are both true—it’s not either one or the other. It’s not that either it’s a dream or it is a reality. It is a dream and it is a reality. And I think they’re both there. —Paul Verhoeven

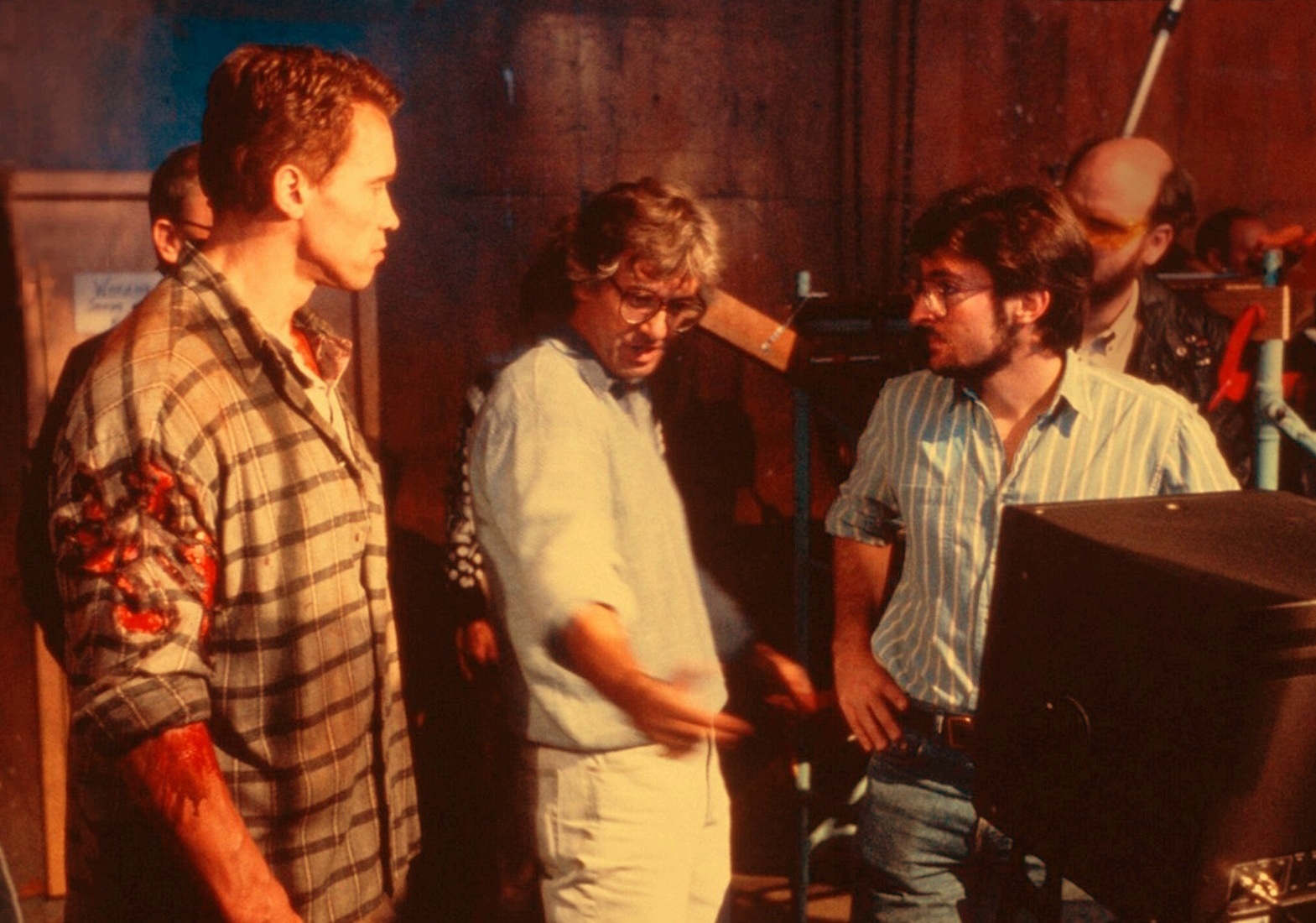

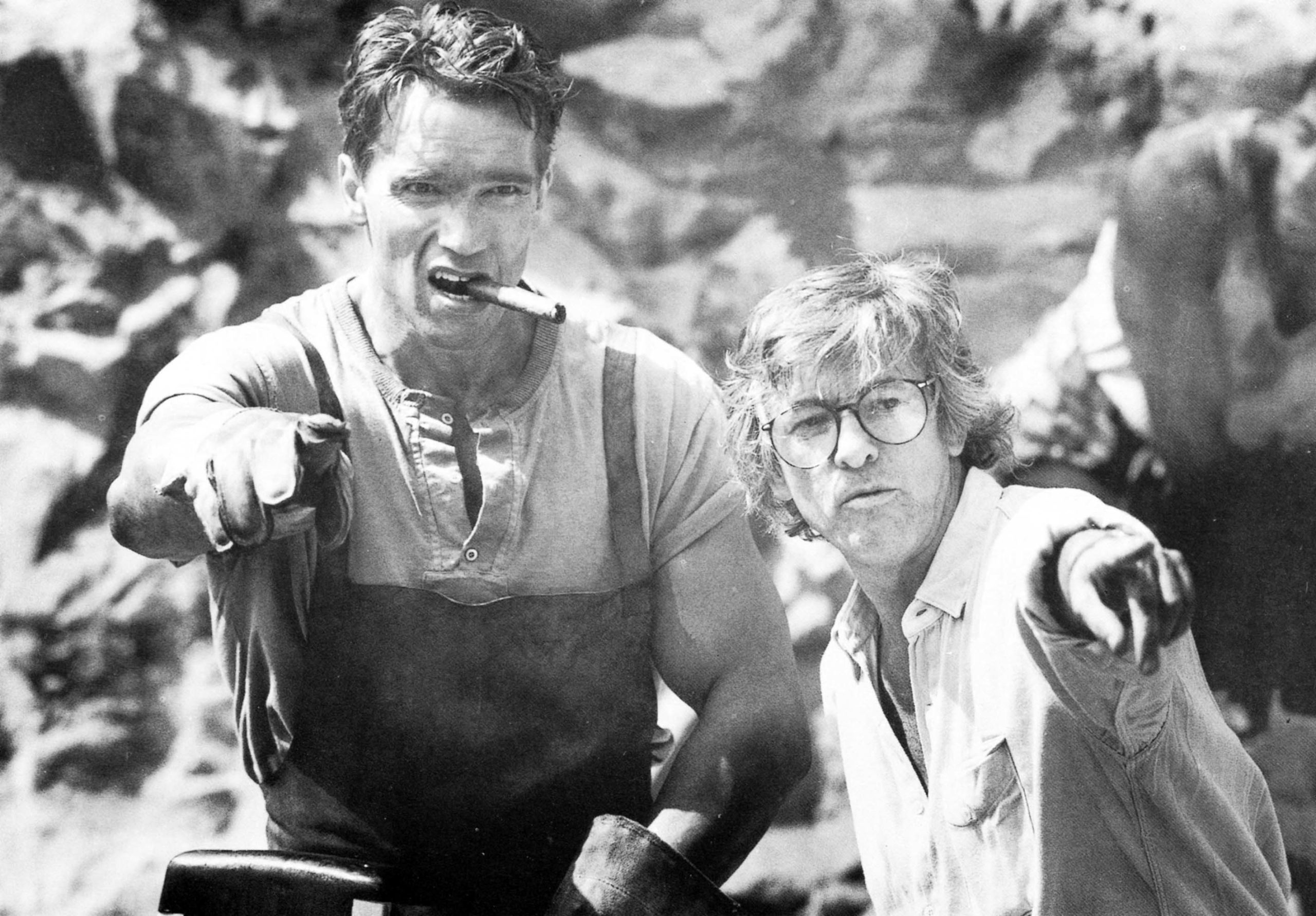

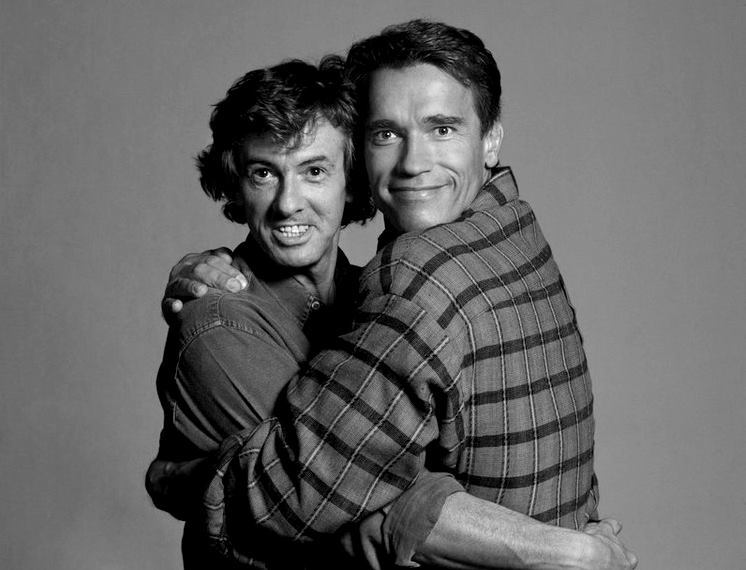

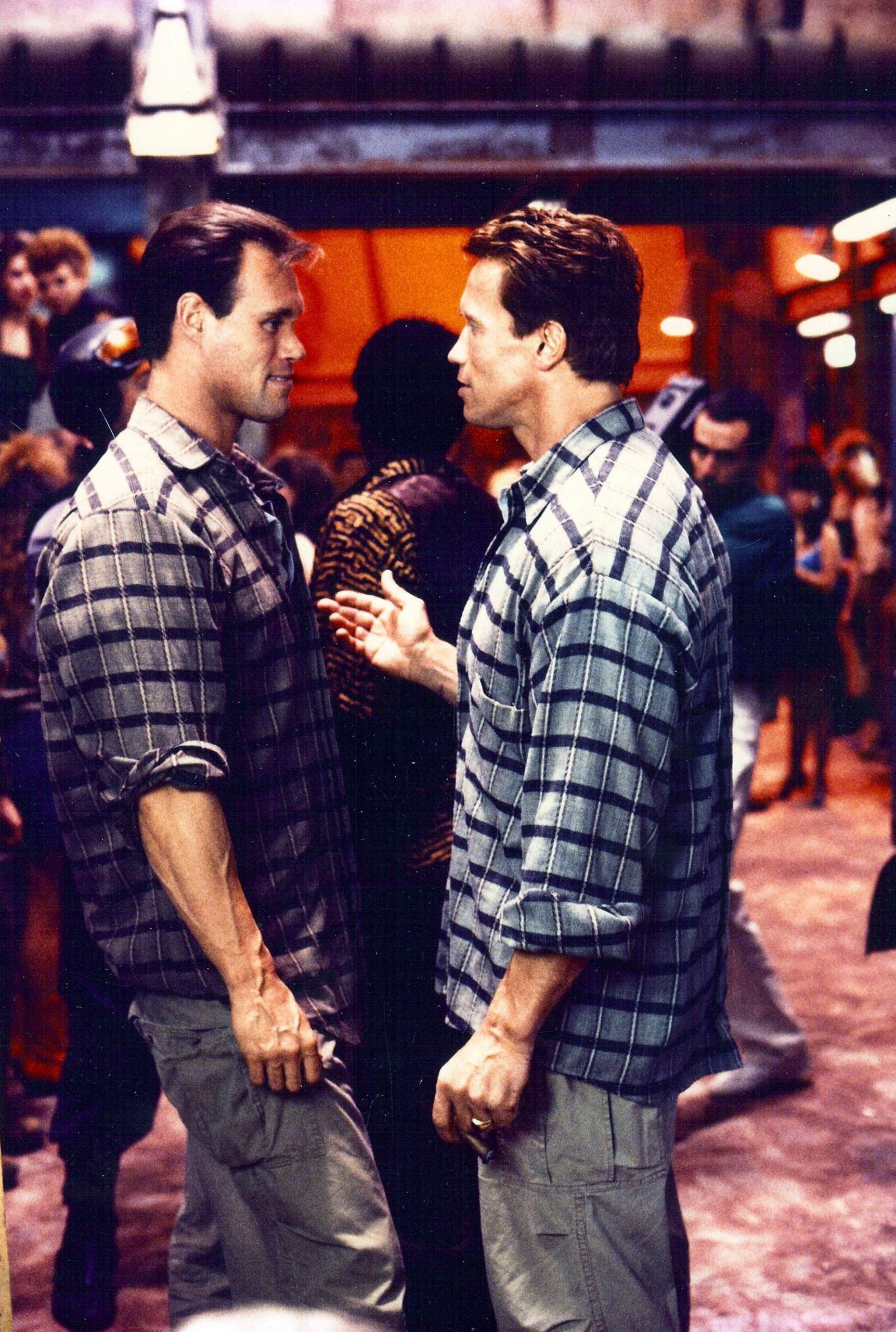

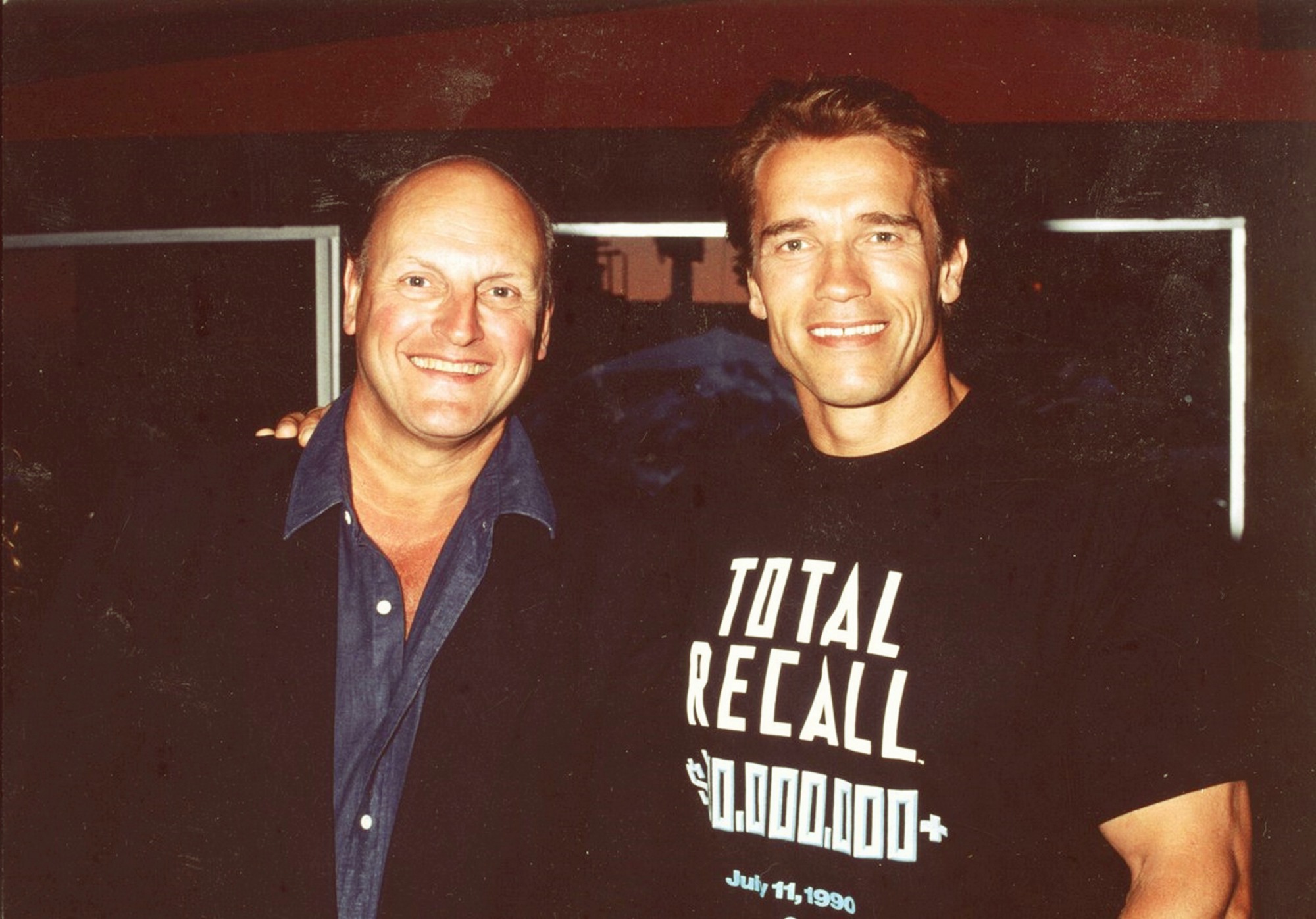

It’s hard to believe that action star Arnold Schwarzenegger and violently gleeful Dutch subversive auteur Paul Verhoeven made only the one film together, 1990’s Total Recall. In this “total mindfuck” of a tale, a humble schmo turns out to be a mind-wiped secret agent who may or may not be imagining a past life on revolution-torn Mars, and may or may not actually be the good guy, being constantly chased almost cartoon-style in a Tom and Jerry switchback psy-op by a permanently pissed-off Michael Ironside. Like mutant resistance leader Kuato and his human symbiont host, the two’s synergy leaped off the screen. Adapted from a Philip K. Dick short story, We Can Remember It for You Wholesale, the duo’s ultraviolent, blackly comedic weird take saved it from the initial “art house” appreciation of the only previous cinematic Dick adaptation, Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep). Total Recall also foreshadows ambiguous reality films that pop up every now and then—The Matrix, Minority Report, Inception—even SPECTRE, if you enjoy Darren Franich’s entertaining take on the final act. The film went through at least 45 drafts of 5000 pages before Verhoeven tossed them and commissioned another screenplay from Ronald Shusett, Dan O’Bannon (both famously worked on Alien) and Gary Goldman. But Arnold was there from the beginning. He had secured the rights long before and aggressively pursued the role of the protagonist Doug Quaid/Hauser, feeling that it was more interesting to see a physically powerful character have the rug pulled from under his reality than a “Dagwood Bumstead” dweeb as originally envisioned. Taking on Verhoeven meant that Arnold was a lock-in condition of the deal. You could say he’d always dreamed of going to Mars…

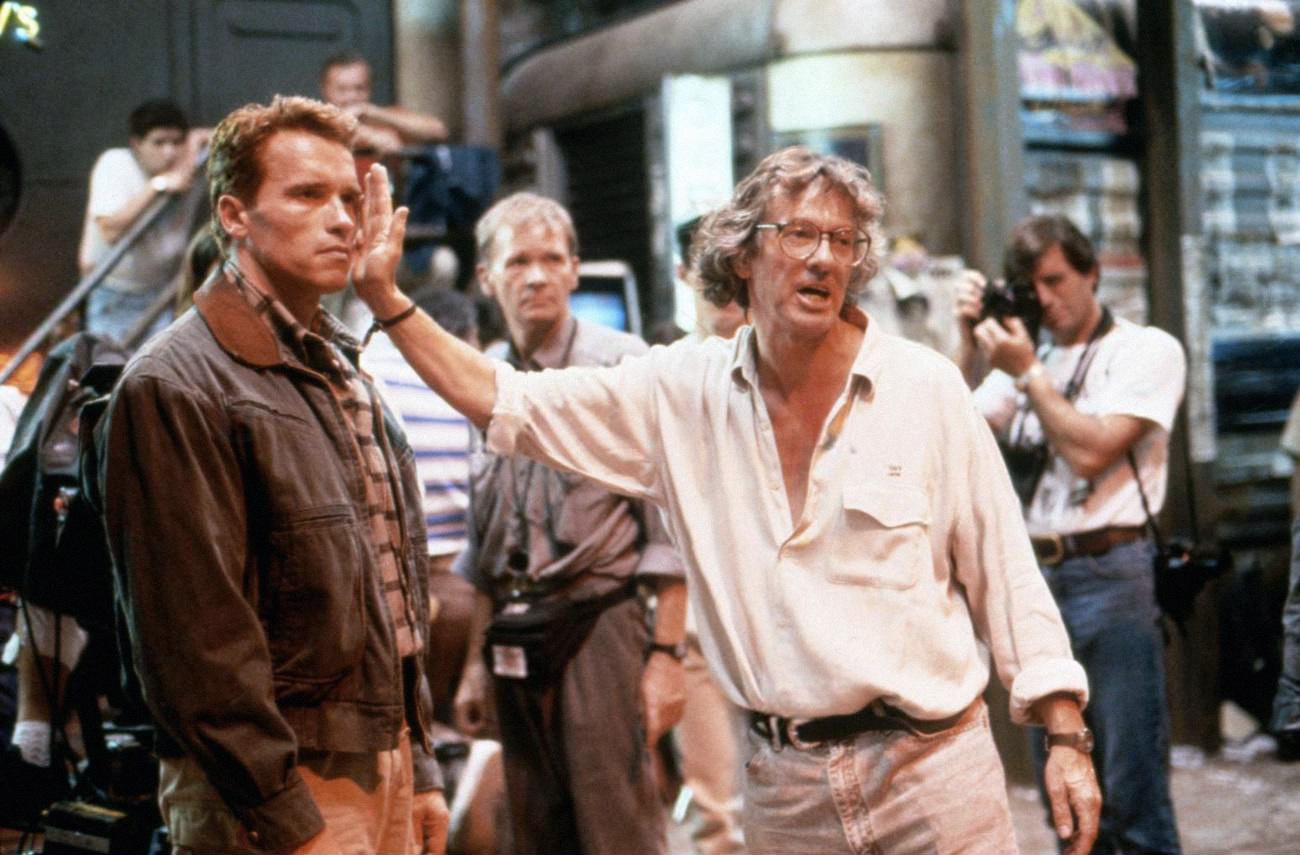

By chance in the late 1980s, Arnold Schwarzenegger went out to lunch to Osteria Romana Orsini on Pico Boulevard in Beverly Hills, and there saw Verhoeven dining. He came over to enthuse about the recently released Robocop, and later kicked himself for not suggesting they collaborate on Total Recall, which had by now fallen out of Dino De Laurentiis’ clutches into those of production company Carolco, who Schwarzenegger had persuaded to snap up the rights. Fortunately the director’s wife believed Arnie and he would make a good match, so it was soon a done deal.

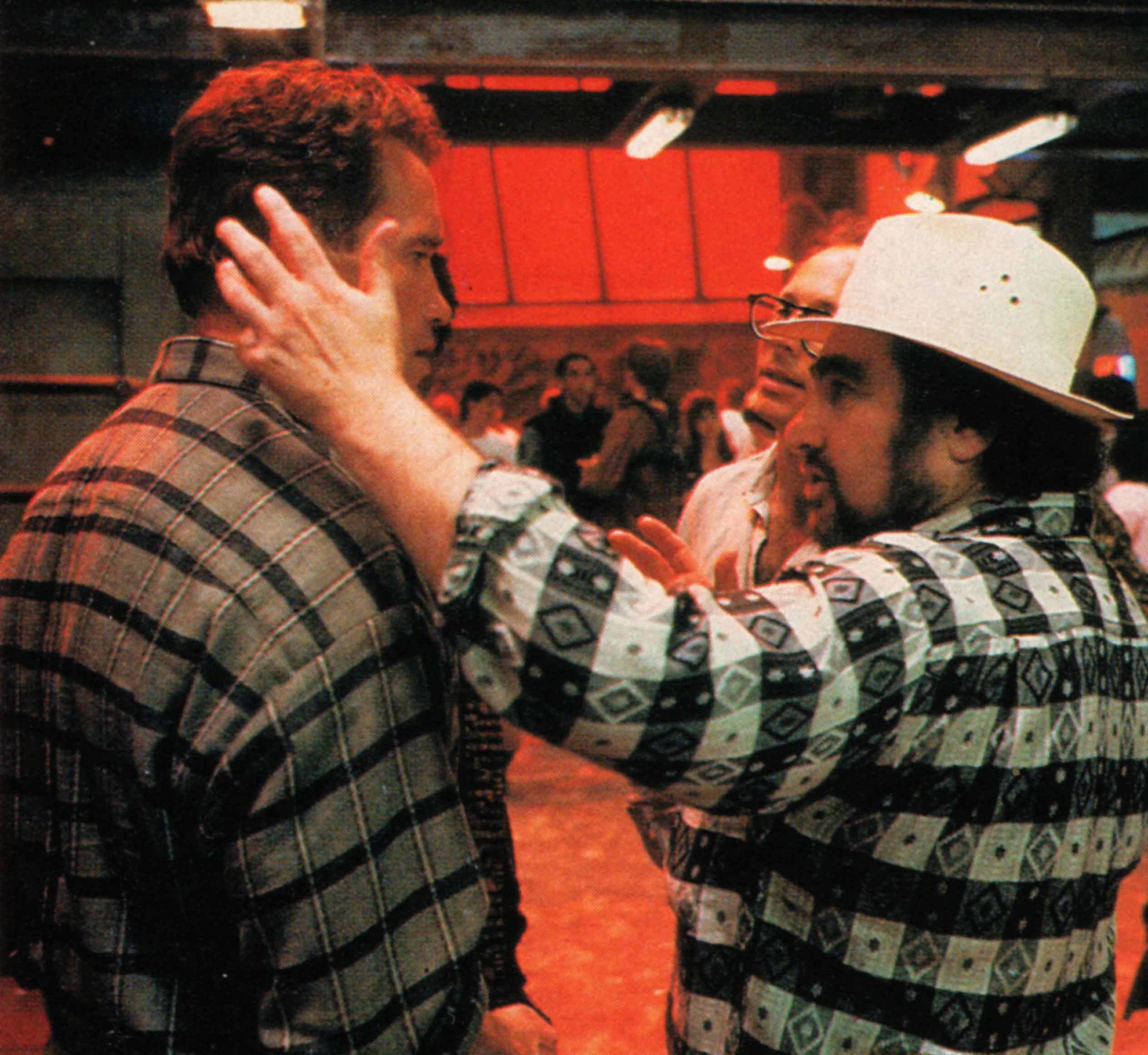

“We shook hands, Arnold and I, and said, ‘We’re going to do this,’” Verhoeven said to The Ringer. “And that was it. No talk about money or anything. It was just looking at each other and believing that Mario (Carolco’s joint founder) could finance it and that Arnold and I were a good team.”

“He was European, so I understood his character,” Schwarzenegger recalled. “And the outrageousness and everything he had done. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen Flesh and Blood. He just has a very great eye and it was very violent. And I thought that’s the way the movie could be.”

The star, according to Verhoeven, “had no ego.” Like with Jim Cameron, Arnold would put himself in the hands of a trusted director for take after take to get the right results. “I’m a big believer in good directors, because if they are really on, then the movie’s going to be on.”

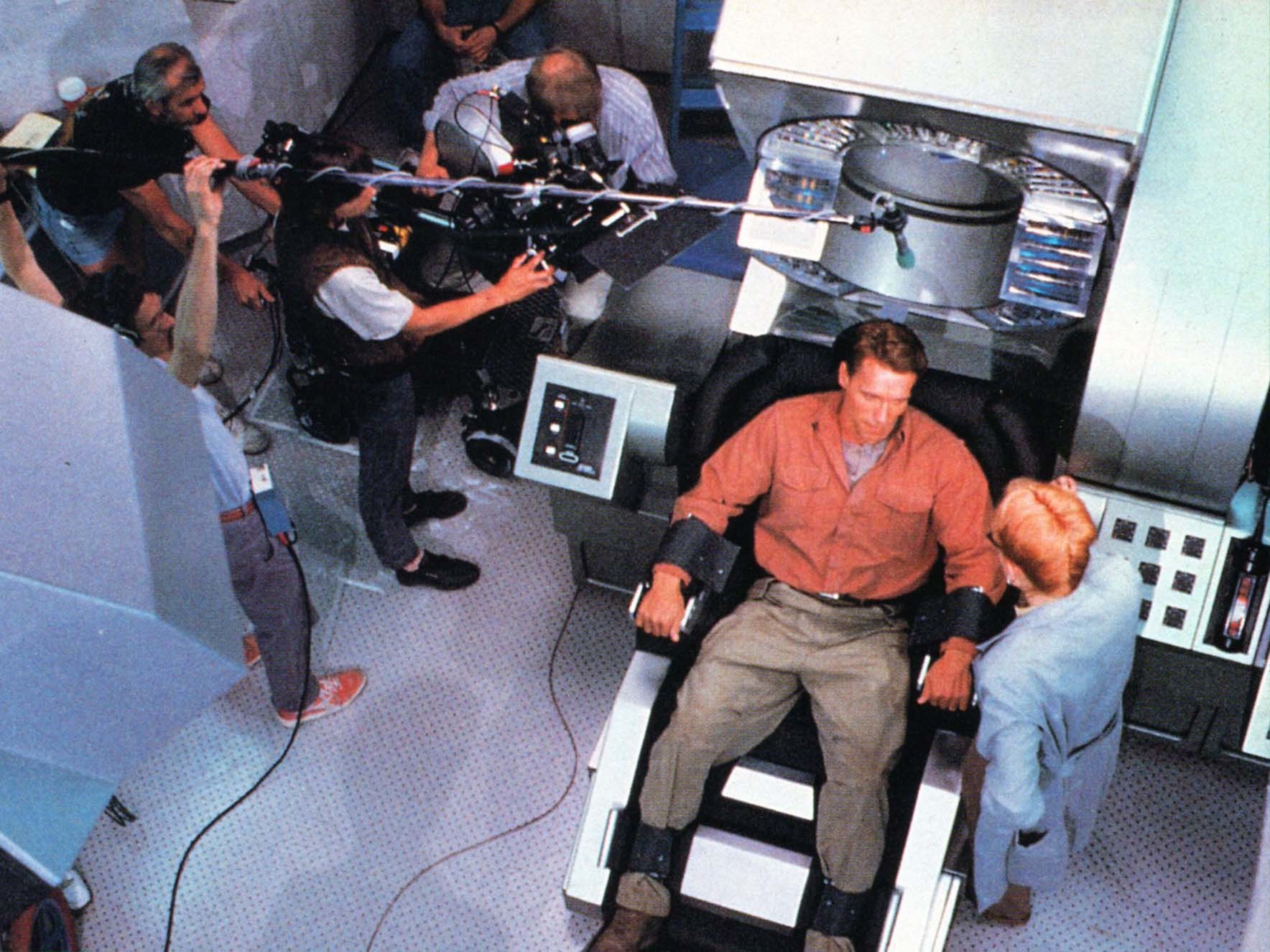

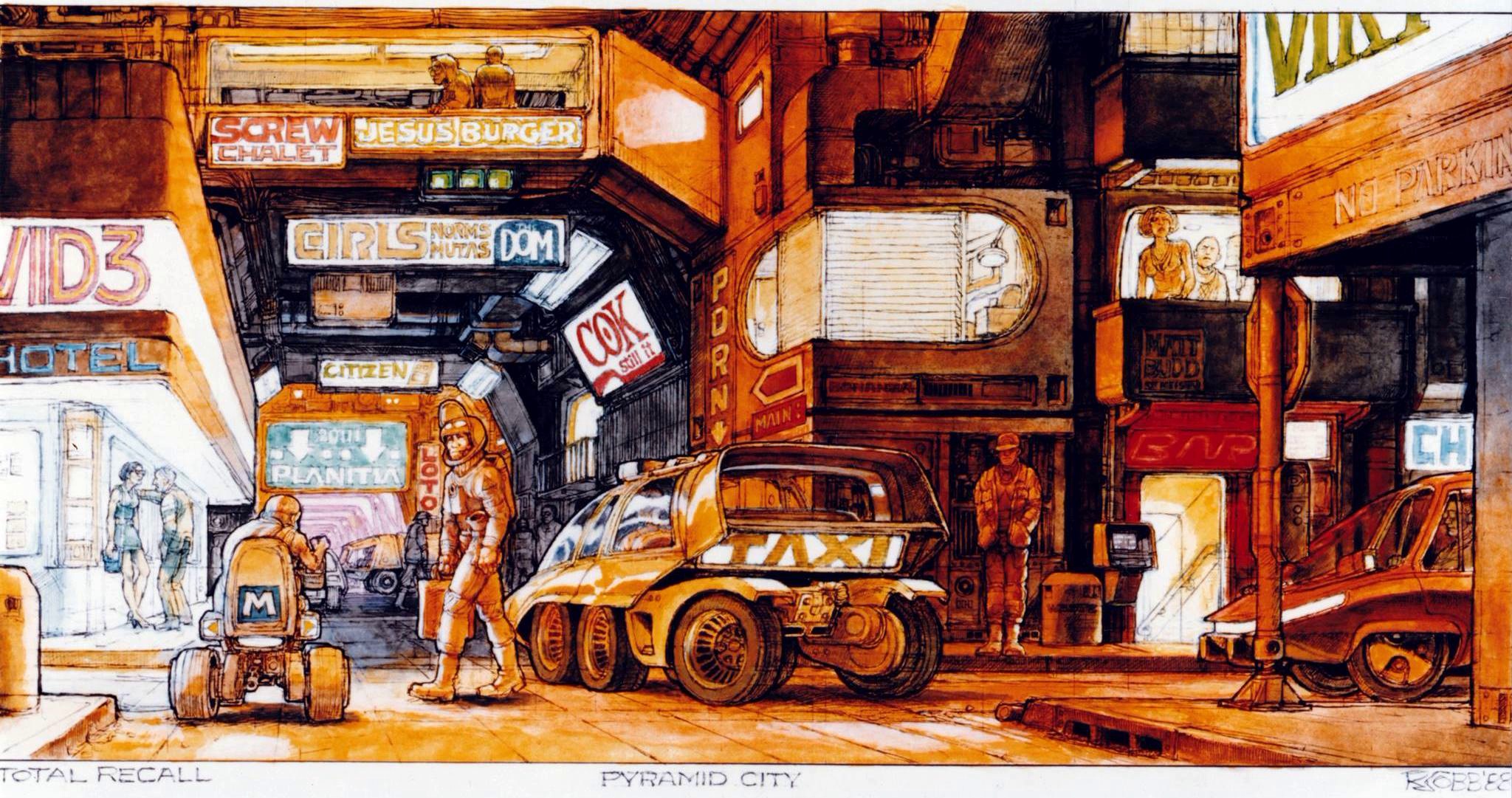

In the duo’s hands, it was definitely on. Arnold performs a multi-layered role. Quaid is alternately a blue-collar construction worker; a charming mind-wiped secret agent named Hauser with unforeseen kick-ass-ness, but like Jason Bourne of the books and later films a hole in his mind; or a dream vacation identity induced by “Rekall” (“For the memory of a lifetime”) being experienced by the recipient of an accidentally induced schizoid embolism. Quaid’s day job with a jackhammer suggests “drilling down” into his subconscious. Interestingly, although it probably had more to do with Arnie’s image, neither Quaid nor Harry (his undercover spy “minder”) wear ear protection or hard hats on site, suggesting an imperfect dream state. Otherwise, the Earth-bound segment is stiflingly solid, grey, brutalist, conformist, its clean lines at odds with Quaid’s dreams of a dirtier, rougher life as a spy amongst the miners of Mars with a mystery diametric opposite rebel girlfriend Melina (Rachel Ticotin) to his perfect blonde, blue-eyed wife Lori (Sharon Stone). Mars is where corrupt colony boss Vilos Cohaagen (Ronny Cox) controls the air supply and suppresses knowledge of an alien artifact that may help terraform the red planet, instead keeping the tourists, miners and mutants (affected by leaking domes) under his thumb, backed up by enforcer Richter (Michael Ironside). Cohaagen’s plot with Hauser/Quaid involves uncovering the mutants’ hideaway and boss, Kuato/George (Marshall Bell).

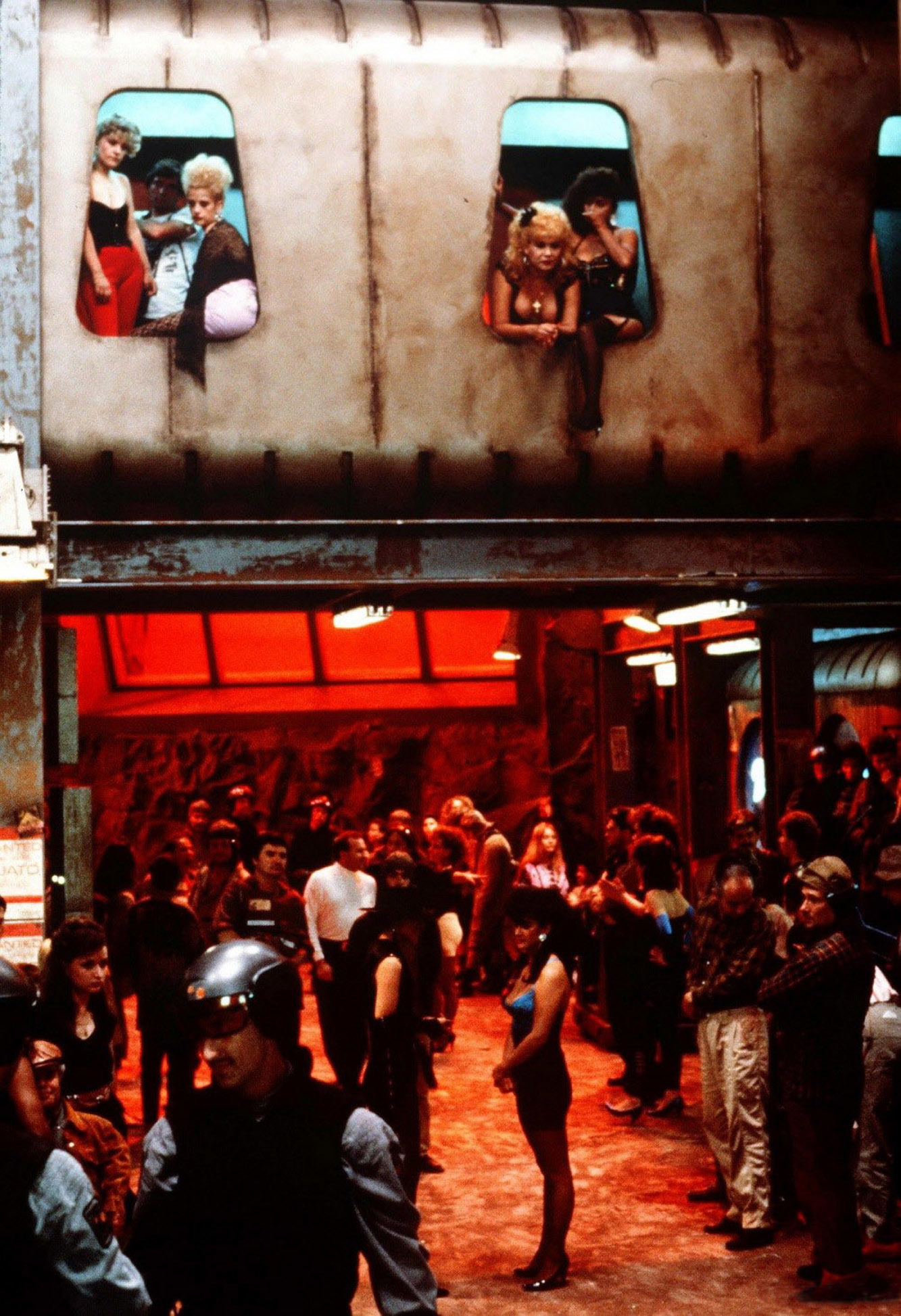

Mars, therefore, by contrast with Earth, is wilder, freakier, and relentless. Red permeates almost every scene set there (handy for the bloodbaths to follow). Cohaagen is bathed in it as he gloats and plots. Red conveys seediness, moral decay, and heightened reality (or abnormality): triple-breasted sex workers that make Benny the cabbie wish he had three hands; an alien leader that emerges from its host’s stomach; children with psychic abilities. So much so that when Dr Edgemar (Roy Brocksmith) turns up at Quaid’s Martian hotel room to tell him he’s in a “free form delusion” and urges him to take the red pill and “wake up” from his “schizoid embolism,” Quaid and the audience almost buy it. By curious happenstance, in one shot where Quaid has his gun on the Dr in front of a full-length mirror, only Quaid can be fully seen in reflection (unless you forensically check), further suggesting that Quaid isn’t really there. Then a close-up reveals a bead of sweat roll down the Doctor’s pallid profile and Quaid blows both him and the treacherous Lori away (“Consider that a divorce” is a killer kiss-off). “The face of Sharon Stone goes from diabolical evil to the most sweet and lovely expression as possible,” Verhoeven said. “That transition for me was so notable. The evil in her eyes changes into the love of her life in a couple seconds.” Thus, he cast her in Basic Instinct.

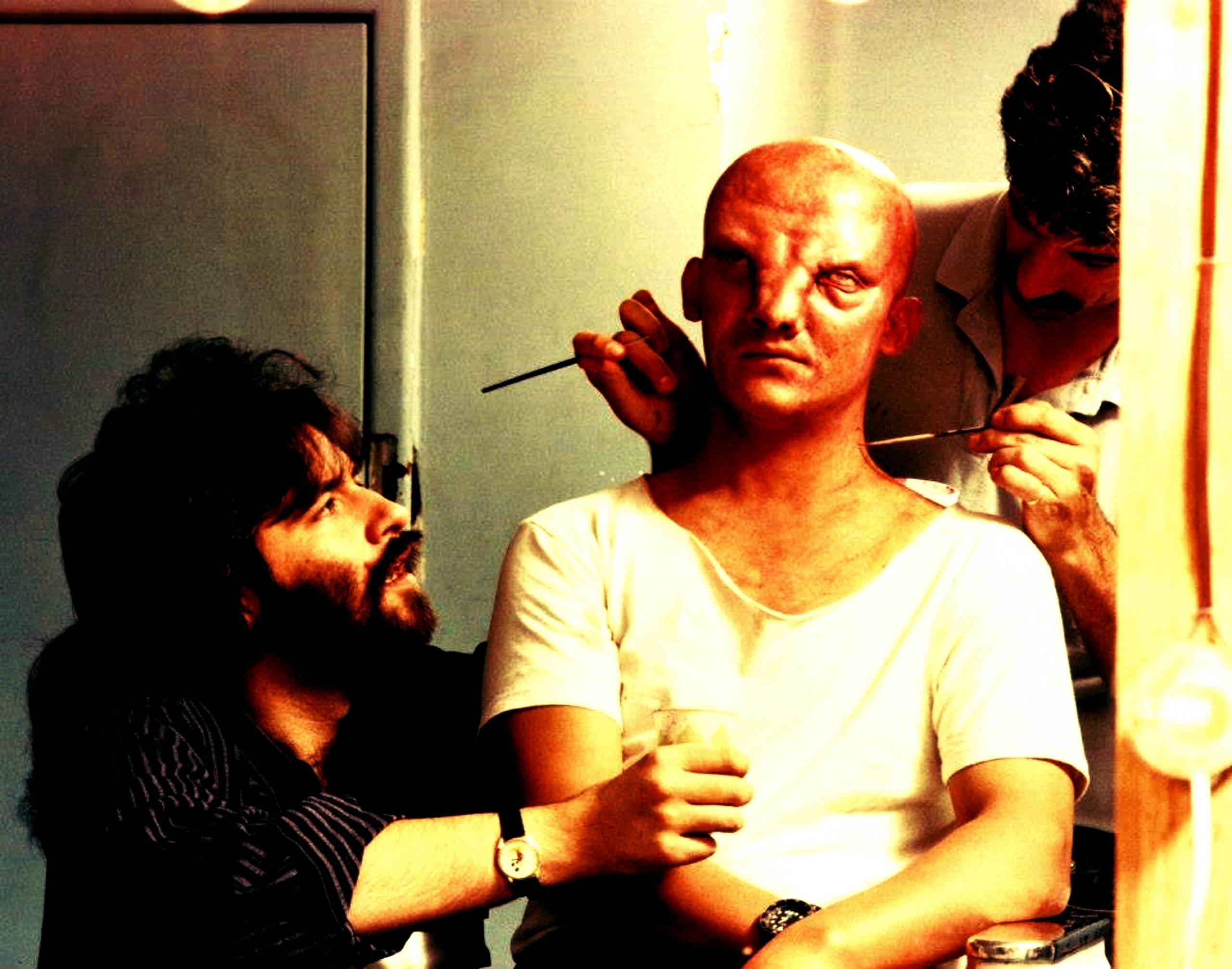

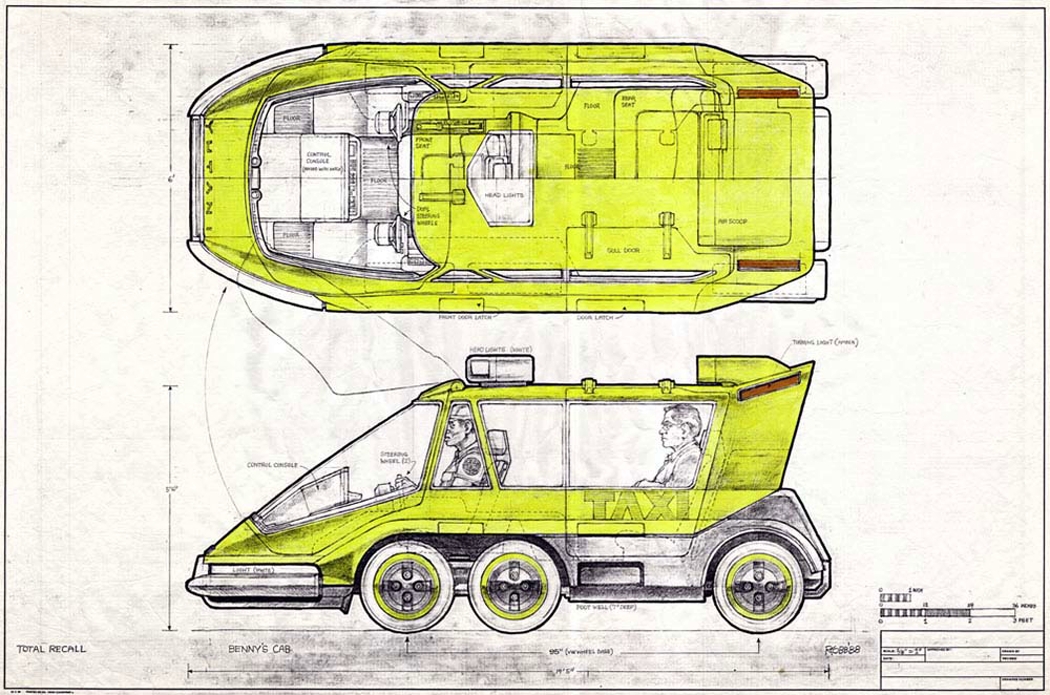

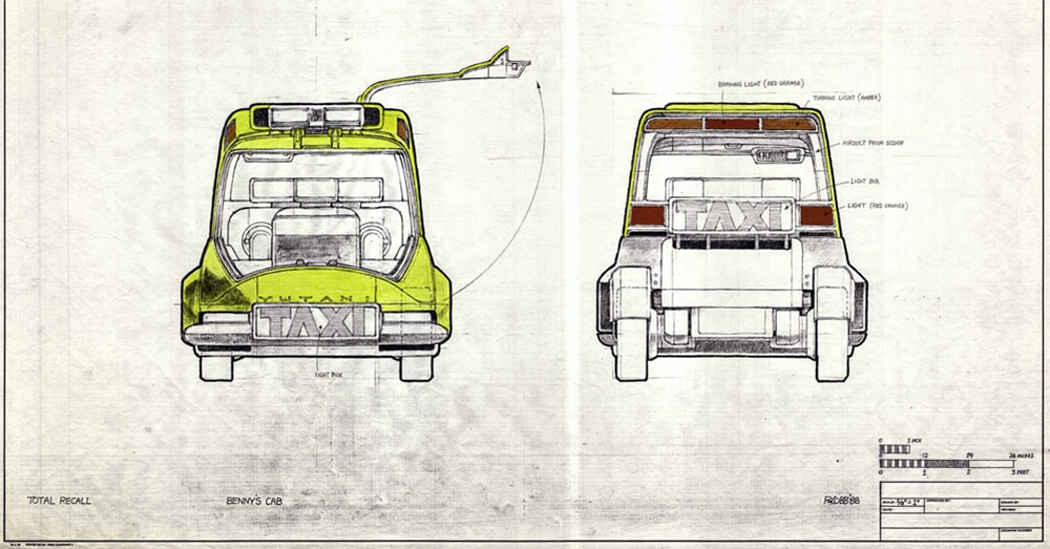

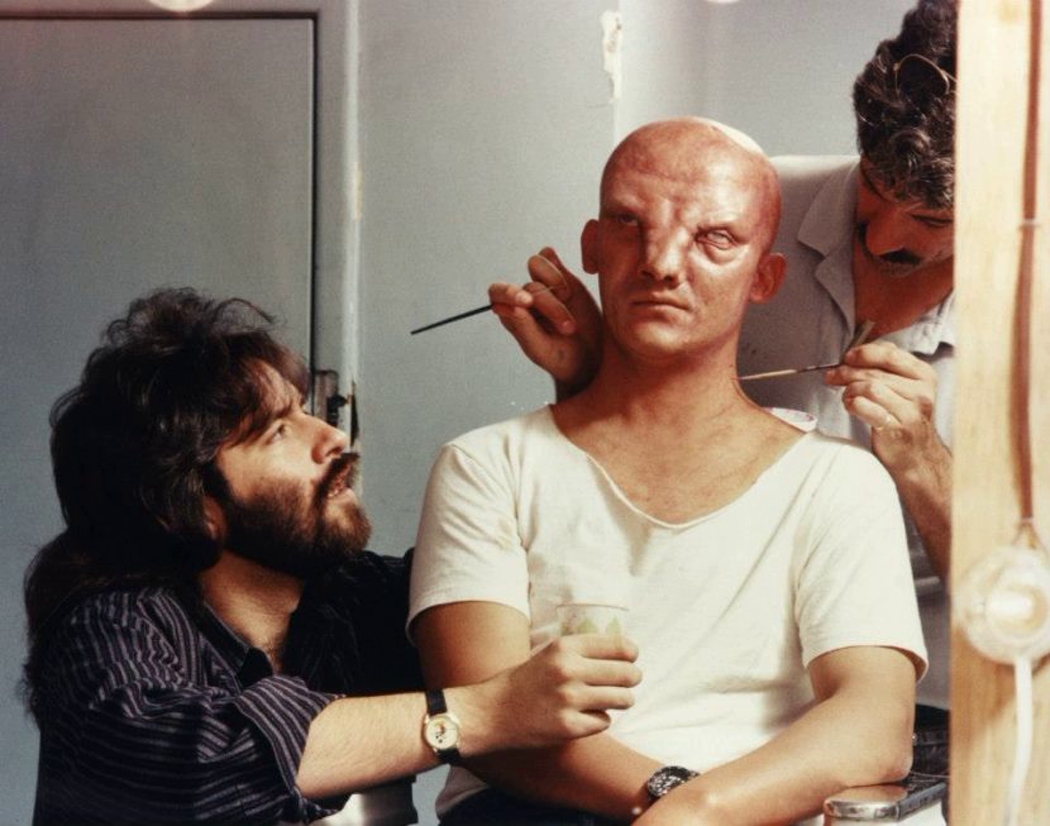

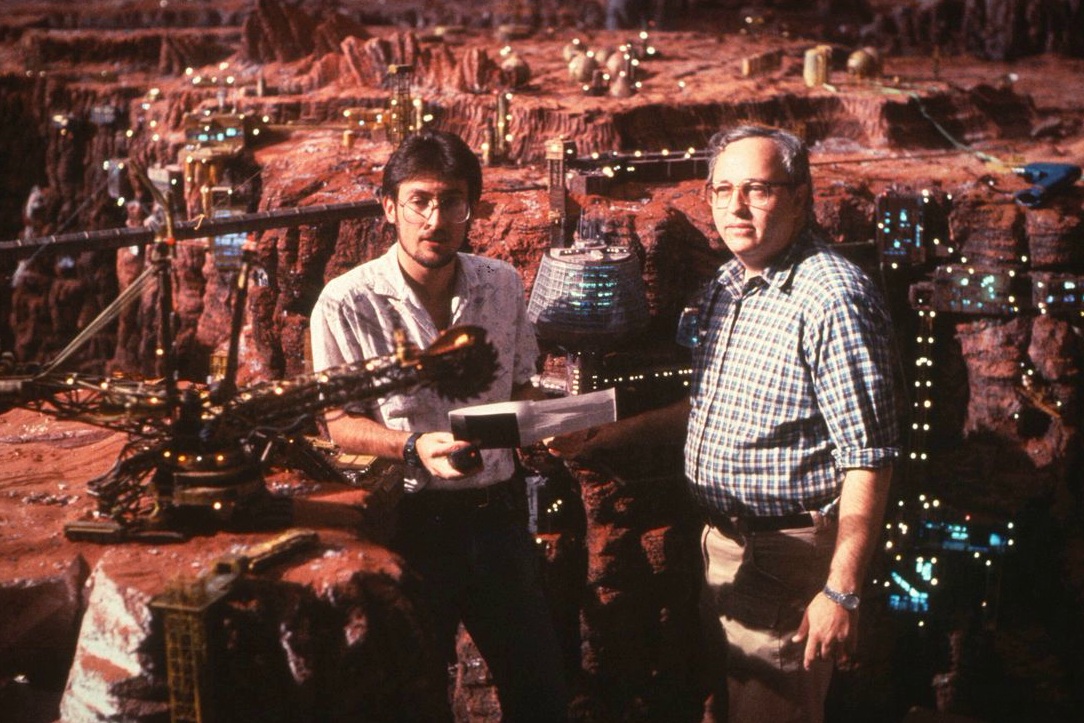

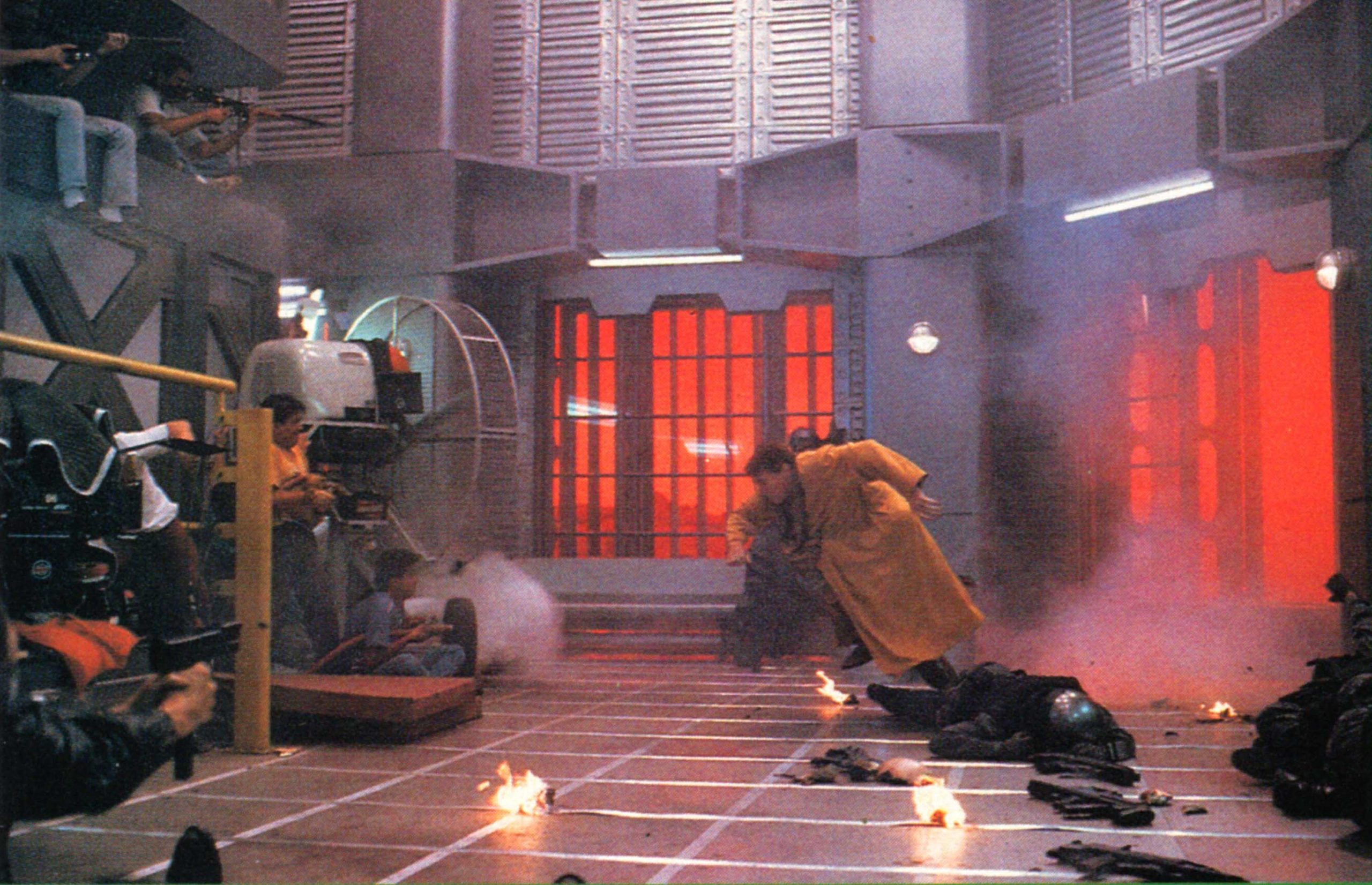

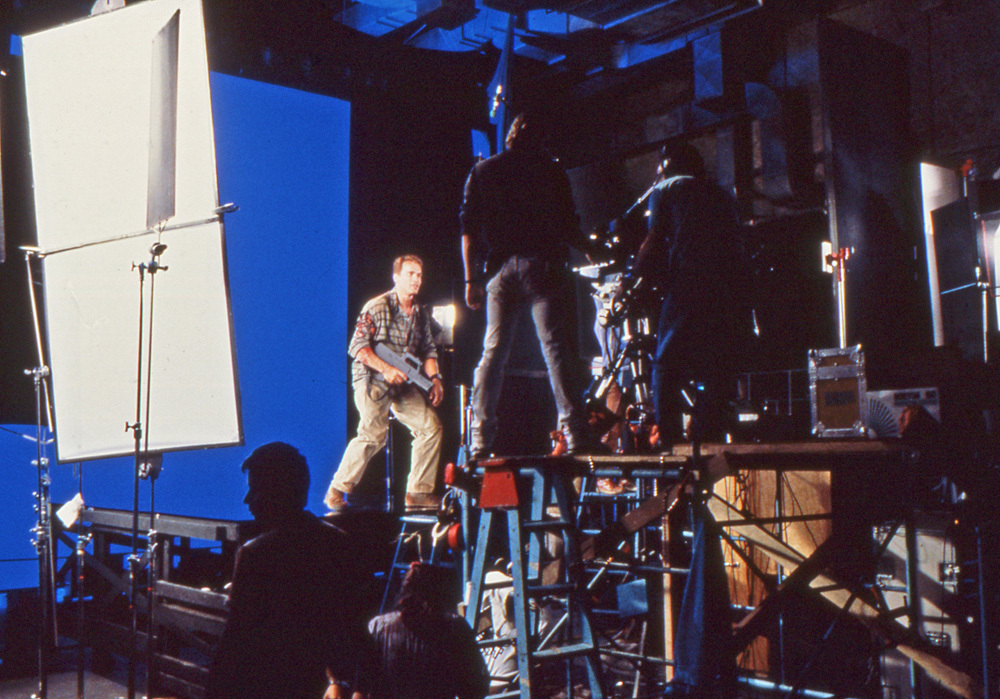

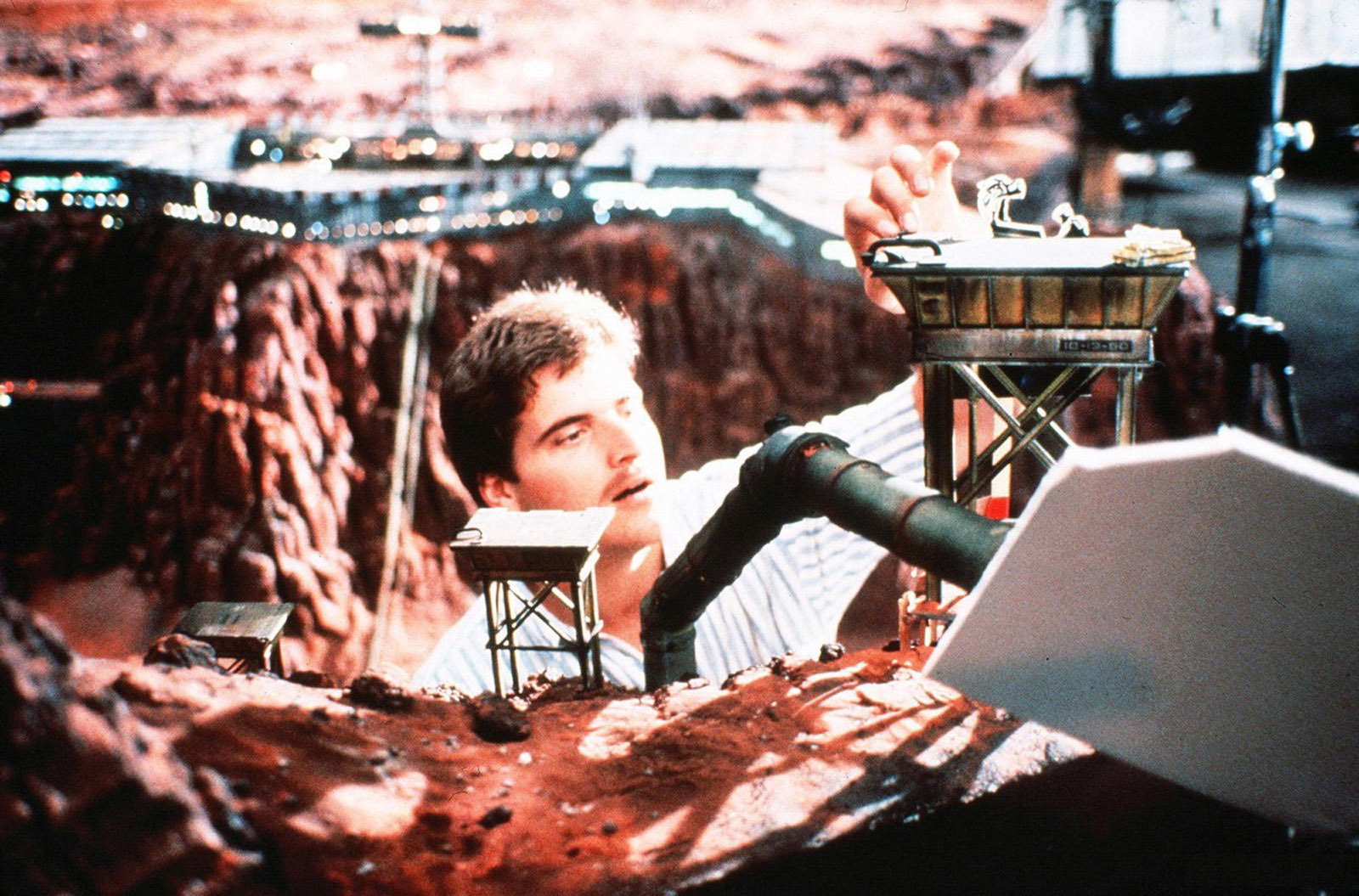

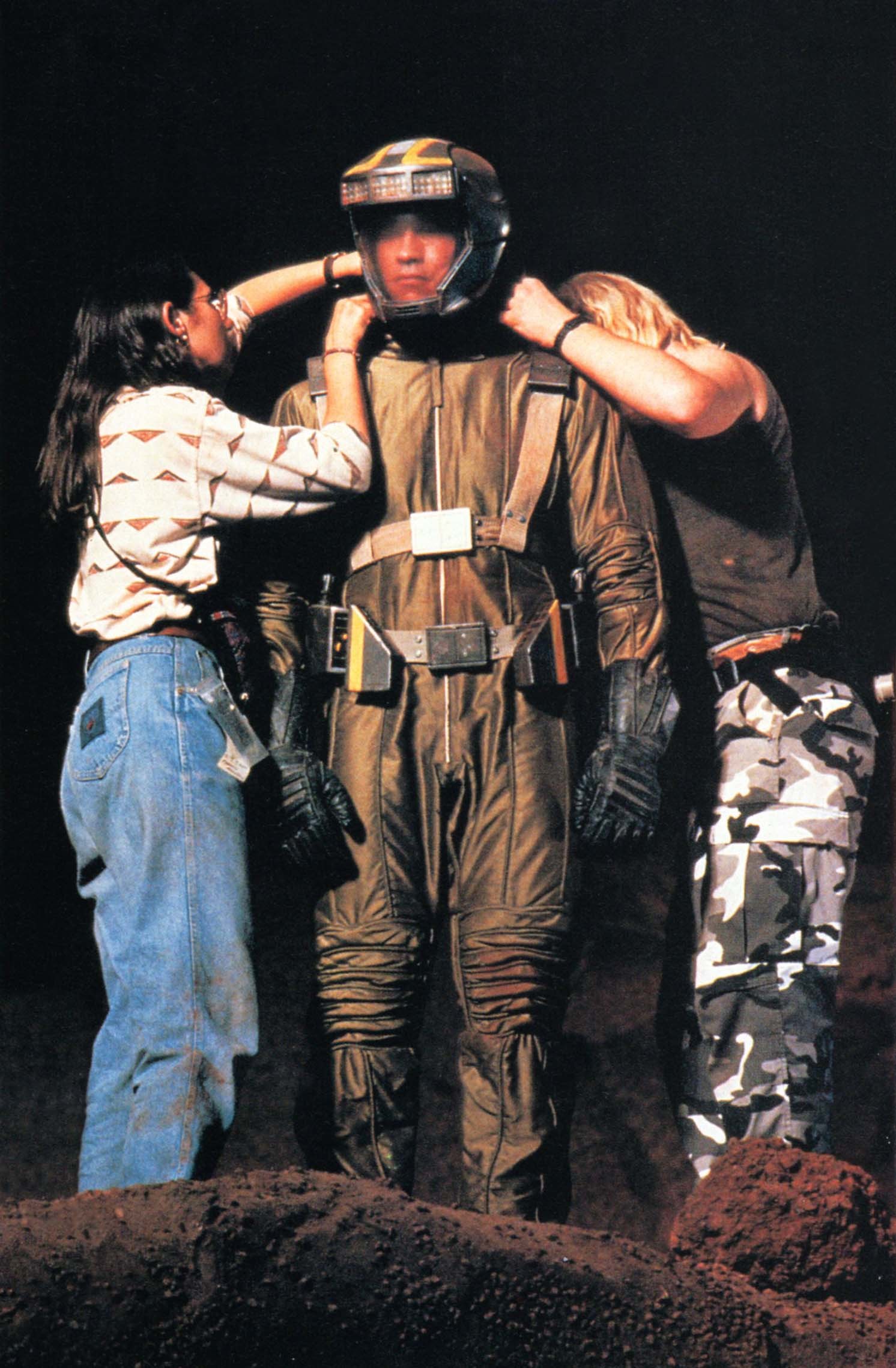

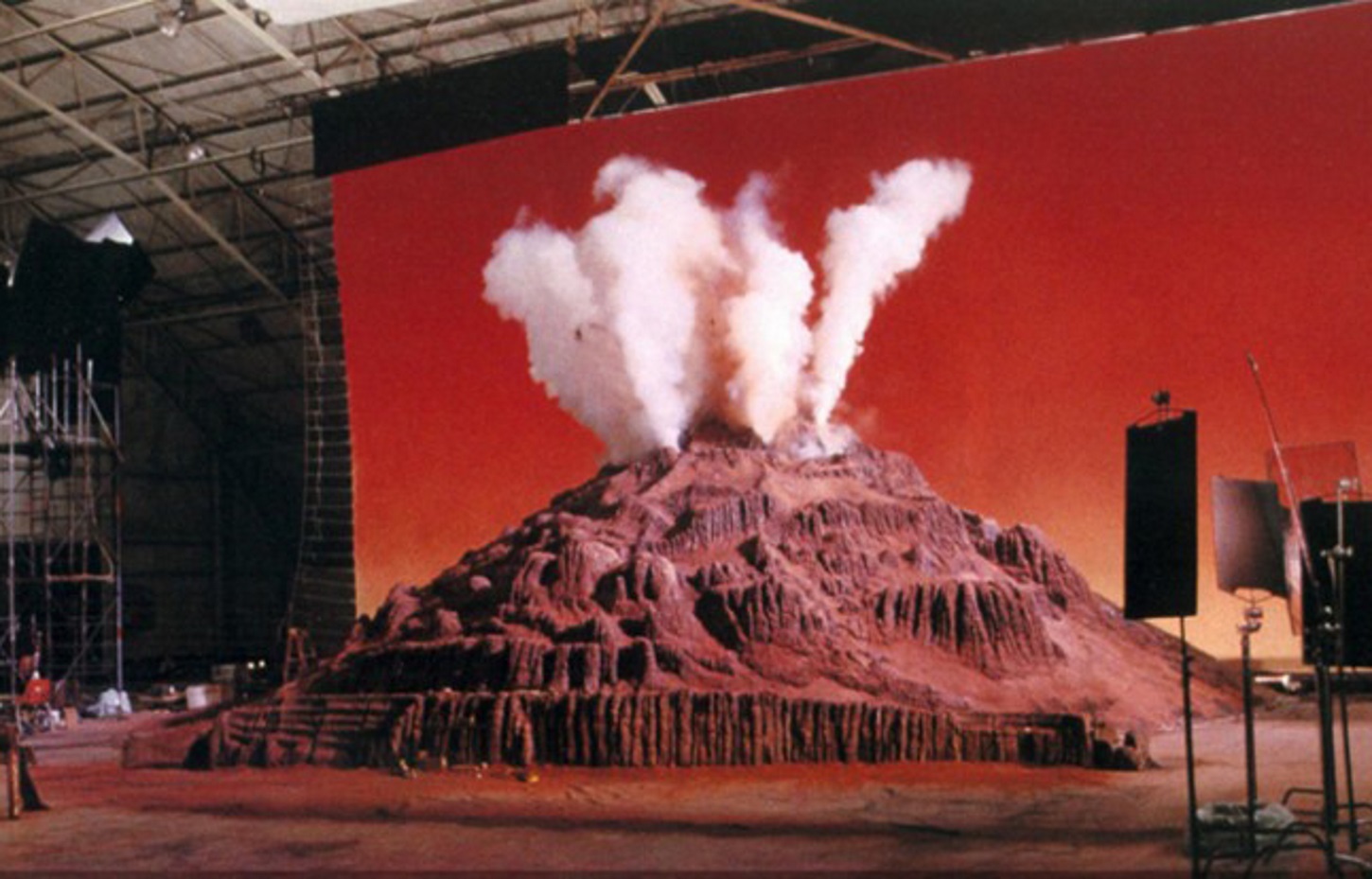

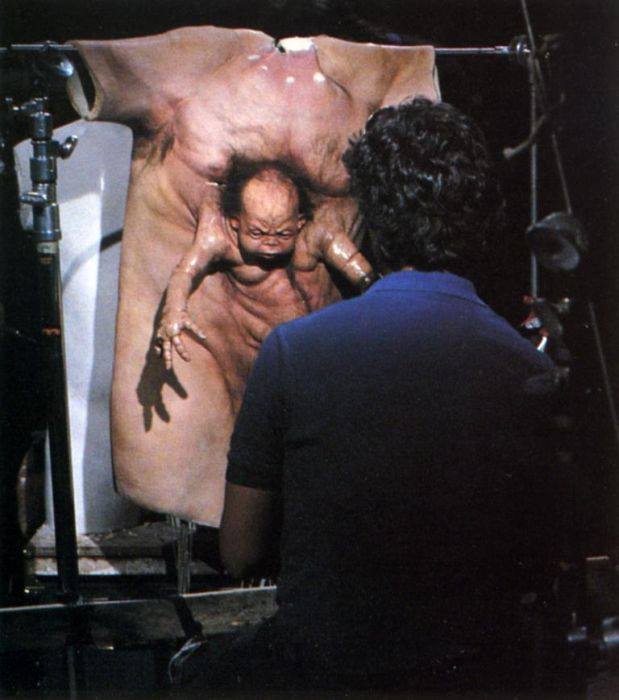

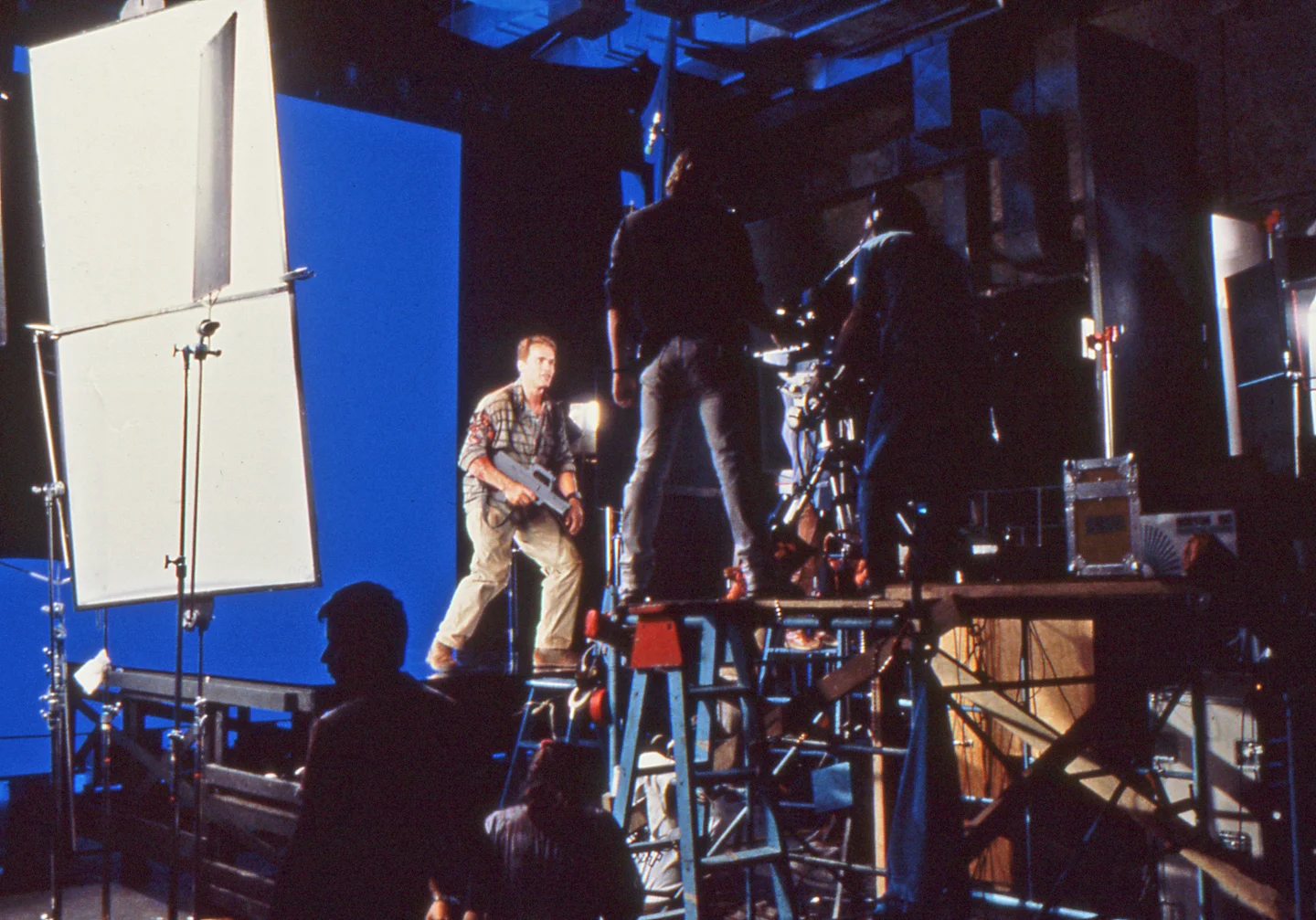

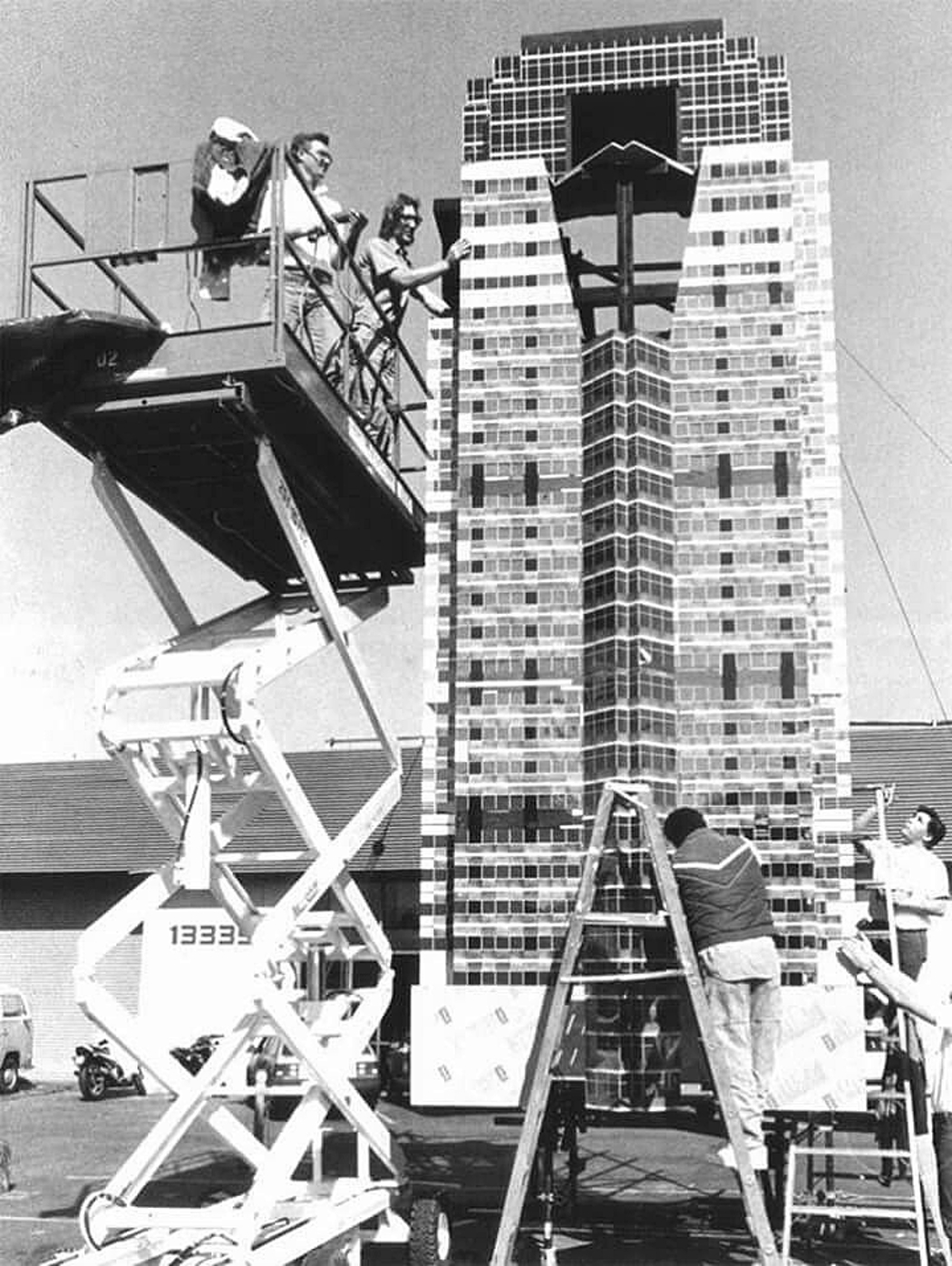

Total Recall cost $63 million, at the time the most expensive movie ever made. Verhoeven corralled a lot of his Robocop crew to work on it. The film successfully meshed practical stunts, special effects make-up, miniatures, optical compositing and CG rendering. At the Oscars, it won the visual effects Special Achievement Academy Award for Eric Brevig (visual effects supervisor), Alex Funke (director of miniature photography), Tim McGovern (x-ray skeleton sequence) and Rob Bottin (character visual effects). Effects such as miniature Mars sets combined with live-action inserts of Arnie on the mine train pulling out from the window and back to a stunning wide shot as the train zooms on. Or the unforgettable and unusual for its day X-ray scanner back on earth, where Quaid is revealed to be carrying a gun and bursts through the glass (the dog in an earlier shot had amusingly stopped and relieved itself in rehearsal). Quaid and Melina use holographic projections of themselves to fox the Martian goons. And of course the self-driving Johnny Cabs. Rob Bottin, who created the Hieronymus Bosch-esque alien transformations for John Carpenter’s The Thing, delivered yet more freaky firsts. Who can forget the site of Arnold extracting a tracking bug the size of a golf ball from his nose? Or the woman’s head malfunctioning disguise Quaid removes at customs before tossing to a bemused guard? Or when he slips and falls in the airless Martian dust, and his eyes and tongue balloon and threaten to pop out of his head? That shot was achieved by employing an air-inflated model of Schwarzenegger’s face.

And then there are the multiple squibs for bullet hits. Never have so many innocent bystanders bought the farm. When Quaid uses a dead civilian as a shield on the Earth escalator, it had to be toned down, although it is still shocking and comic. Verhoeven: “I always had trouble with the MPAA. The censors do not understand, though, that when you cut, it actually becomes more violent. When you cut it down it loses the over-the-topness and the comic book element. If you shorten it, it becomes more realistic.”

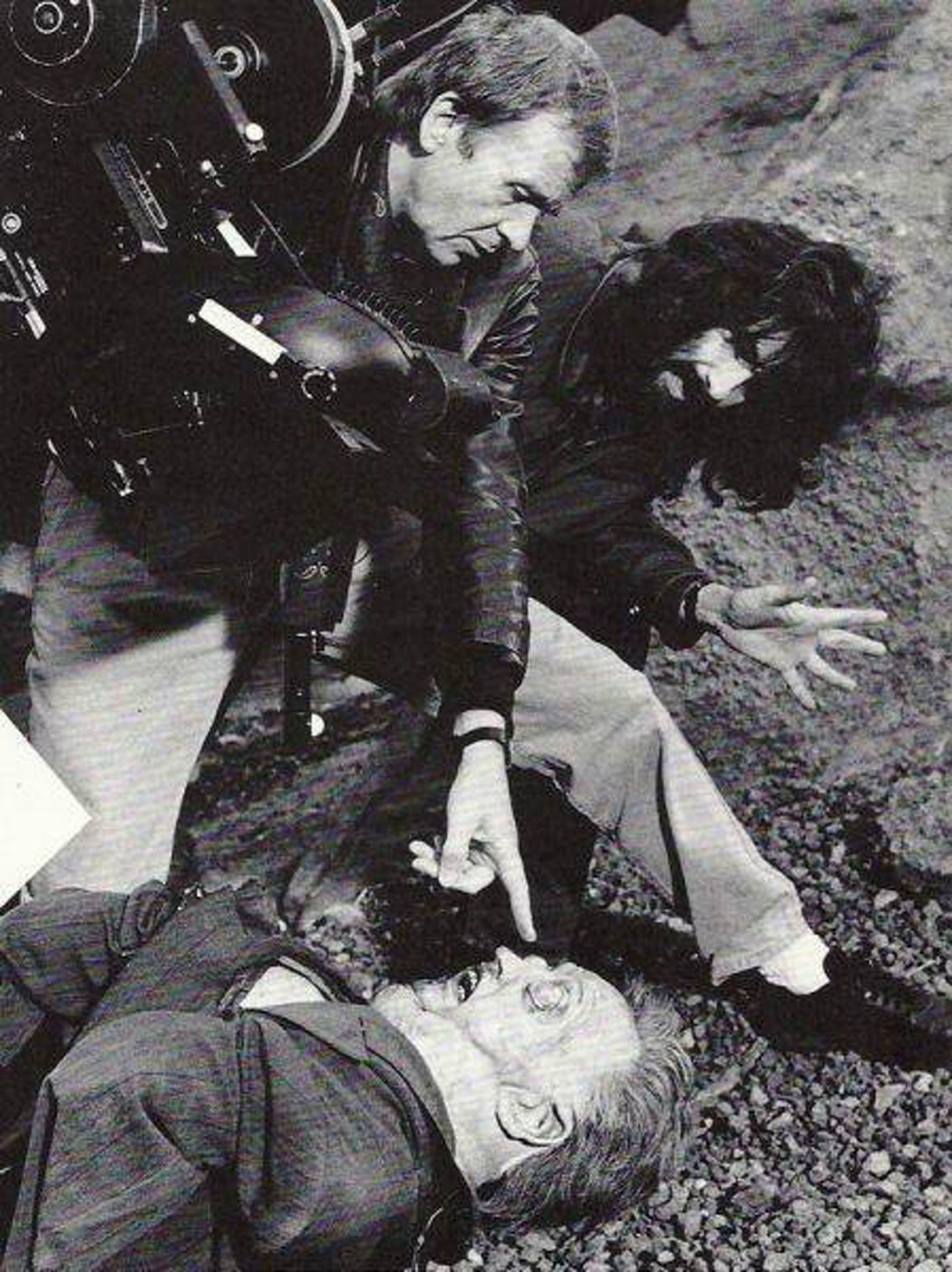

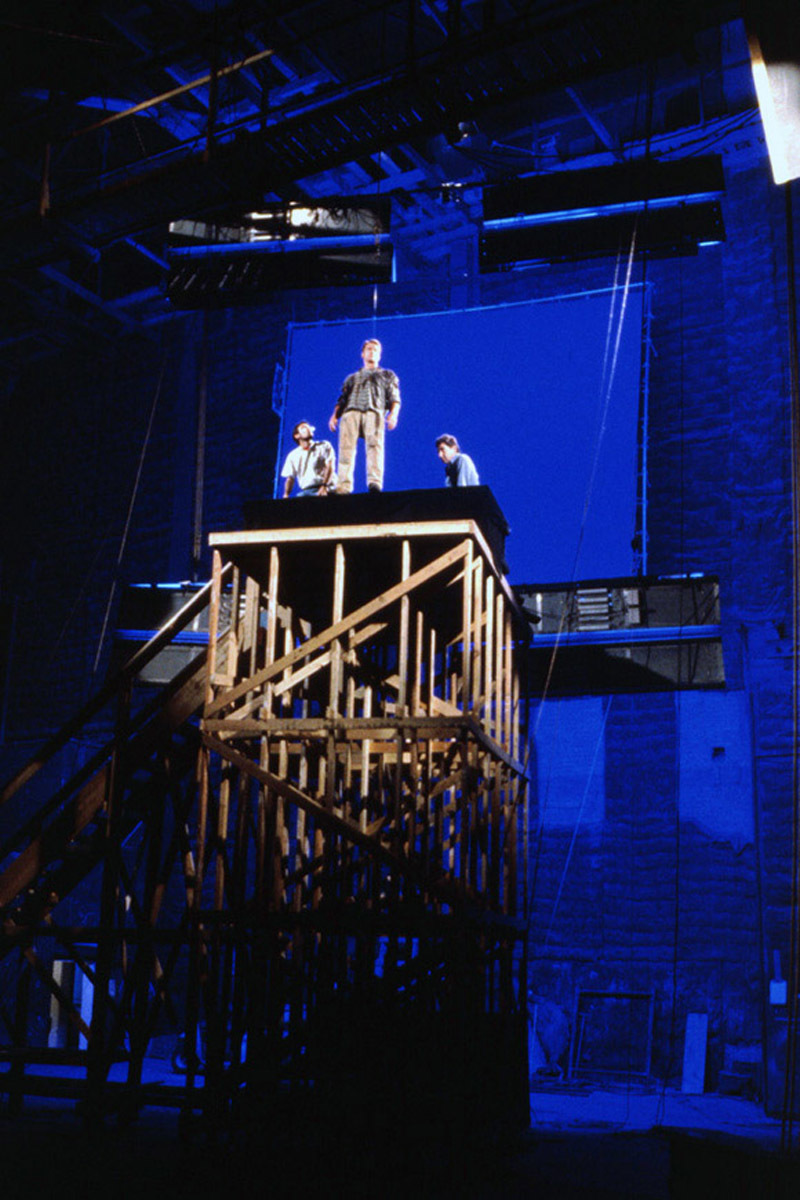

The production took over Mexico’s massive Churubusco Studio in Mexico City, where David Lynch filmed Dune in 1984. That may have been a hold-over from when De Laurentiis held the rights, as he had previously availed of tax breaks for Dune there. The producers insisted because of the scale Verhoeven take on a second unit director, and stunt co-ordinator Vic Armstrong was the man for the job. The director took a while to delegate—Armstrong’s first shot was the close-up of Arnie’s drill tip on the building site. Five months later, he had four cameras, working on multiple scenes. Although he didn’t shoot the scene where the Martian windows blow out and Arnie and others seem to be pulled toward the decompression, he planned it methodically. Back then, it was very expensive to do wire removal digitally. His solution was to pull the actors and stunt performers along the ground by wires. Then, when they were being dragged up and out, they’d be connected by wire harnesses attached to their waists, but shot from the waist upwards. And finally, for wider shots, a vertical set was built and the camera put on its side so it looked like they were literally suspended in mid-air, pulled by the enormous drag of the atmosphere leaking out.

Months later, Verhoeven was shooting it and getting more and more pissed off that the wires were visible. Turns out the producers had skimped on the cost of the vertical set segment. In the end, they backed down. “It was a trick I learnt from Alf Joint,” Armstrong recalled in his memoir, The True Adventures of the World’s Greatest Stuntman. “They did those sorts of things on old movies like The Thief of Baghdad back in silent movie days. But people don’t use techniques like that nowadays.”

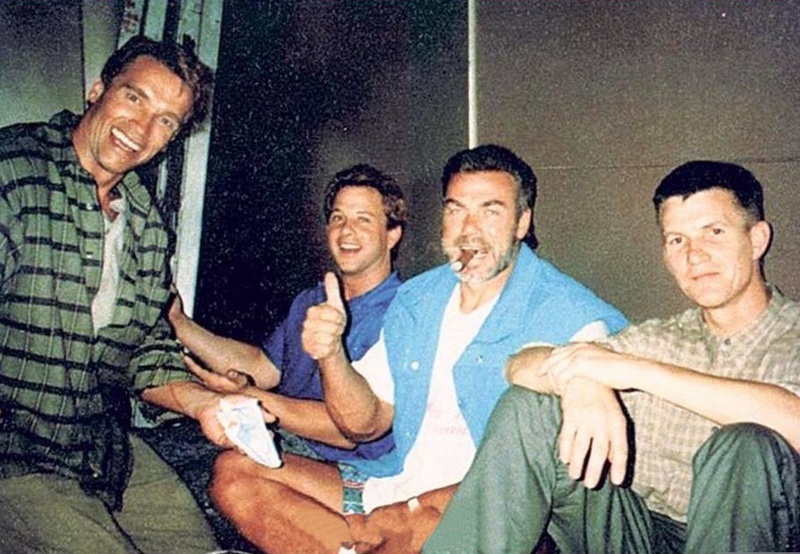

Arnie worked hard and played hard on set and after each day, to keep spirits up. Many of the crew suffered from “Montezuma’s revenge” in the heat. Verhoeven at times directed from a stretcher on top of a minivan, attached to a saline drip, to avoid insurance penalties. At the wrap party Arnie had water pistols for everybody at their tables. After the speeches Arnie led the mayhem and soon vodka and red wine was replacing the water in the pistols.

Of course, post-production includes one of the most important elements of Total Recall’s success—the fabulous score by maestro Jerry Goldsmith. When Dino Di Laurentiis held the rights the film was to be scored by Basil Poledouris, and the deep Brass intro to the main score does suggest his signature style, perhaps in tribute. Initially the producers sent Goldsmith to work with musicians in Munich, to save money. However, after a few disappointing days, Goldsmith insisted on working in London with the superior National Philharmonic Orchestra, whose musicians had worked with Goldsmith before and knew what he was after. Although the score permeates the action of the film, it isn’t very lengthy, being mostly composed of percussive-driven cues. Goldsmith also delighted in composing the background music of elevator muzak and the Rekall inc advert that plays on the subway as Quaid makes an early escape.

The relentless chases upon chases and fight scenes in the film required Goldsmith to produce a large canvas of dynamic, fully orchestral material. As well as traditional touches, he supplemented the music and plot developments with electronics, suitable for the “is this all a dream?” surrealism. In “The Mutant,” this is shown off to its best effect with the visuals as a dream-like sequence of free-flowing flight and quick cut wisps of zooming, surging movement reveals the massive alien device hidden within the pyramid mine.

At the end as Quaid and Melina activate that device which improbably produces enough air for all of Mars to breathe and save their lives in double-quick time as they struggle to breathe, we—and they—are still faced with the question of whether this is all real, or, as Quaid asks, “I just had a terrible thought. What if this is a dream?”

“Well, then,” Melina replies, “kiss me quick before you wake up.”

The ending is ambiguous, as Verhoeven and the writers intended, also setting a template for the likes of risky endings like Memento, Inception, even the cut to black “Don’t Stop” much-debated fate of Tony Soprano on television. What is not in doubt is that Total Recall remains an action tour de force R-rated violent trip that became the fifth highest earner for 1990. As Johnny Cab might say, “We h-hope you enjoyed the riiiide!”

Tim Pelan was born in 1968, the year of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (possibly his favorite film), ‘Planet of the Apes,’ ‘The Night of the Living Dead’ and ‘Barbarella.’ That also made him the perfect age for when ‘Star Wars’ came out. Some would say this explains a lot. Read more »

“There’s a long story to ‘Total Recall.’ The first script was written in ’79 by Ron Shusett and Dan O’Bannon, the writers of the first ‘Alien,’ and then in the ten years that passed between the first draft and when I started to work on the movie, which was ’88 or something, they wrote together with some other writers twenty-five drafts of the same screenplay. There were seven directors involved, and I think several producers and coproducers, and they started the movie several times, and it always fell apart. And so when I got the script I had twenty-five drafts to go through and to select from. Then filming you found out that first of all you have to select out what you’ve got for Arnold. There was never an Arnold Schwarzenegger role in the movie—it was about a very normal guy, physically, I mean. Arnold is very normal, but he has this kind of physique that is bigger than life, isn’t it? But this was written for somebody who looked like Woody Allen, somebody like that, and so we had to rewrite the script completely, and alter the third act completely. I think in both movies the structure and essential elements of the script were pretty much given to me, and mostly what I did was to build the building based on the blueprints, and with the European movies I think I was more part of the blueprints.” —Paul Verhoeven

Screenwriter must-read: Ronald Shusett, Dan O’Bannon & Gary Goldman’s screenplay for Total Recall [PDF1, PDF2]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

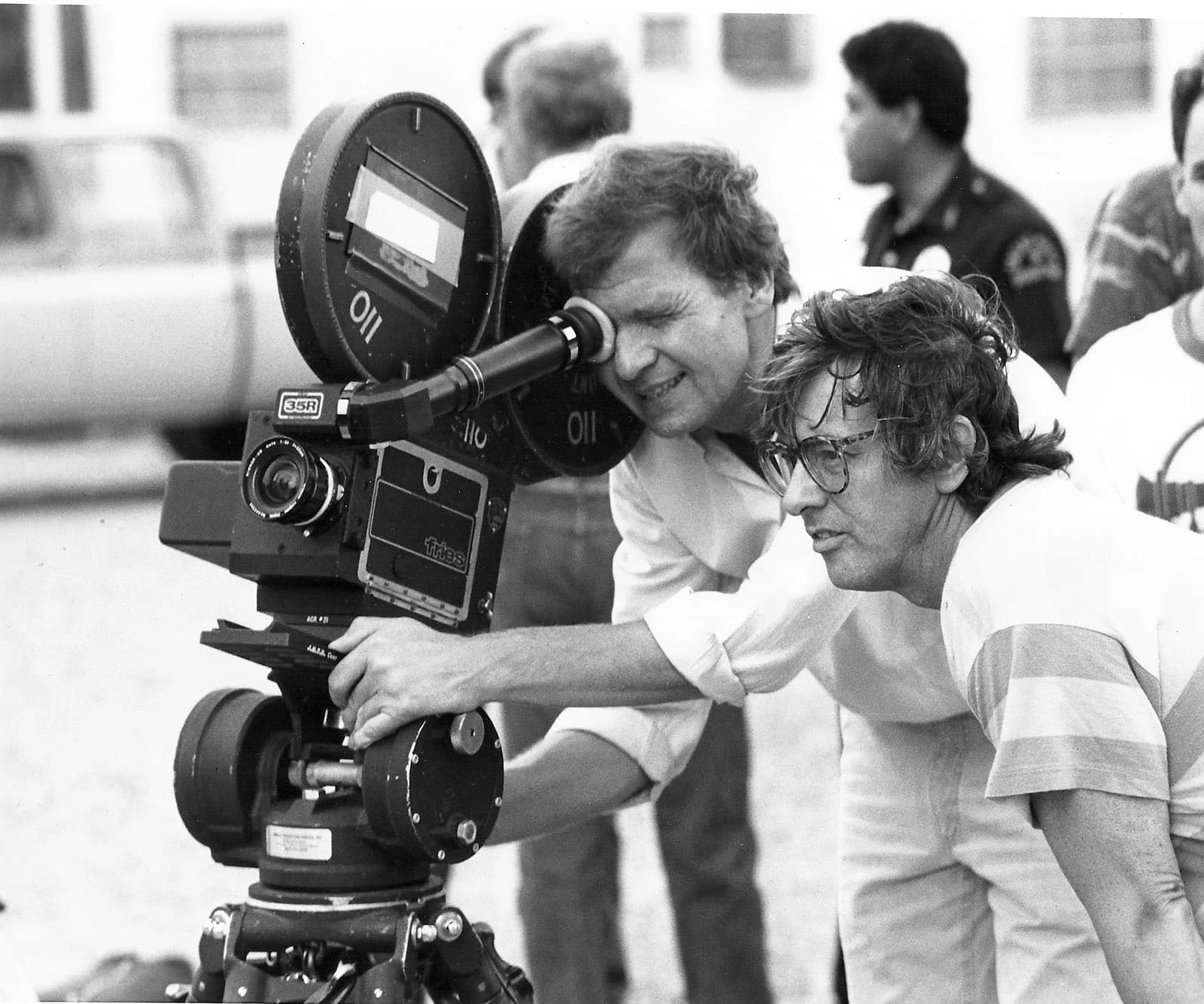

Director Paul Verhoeven on effects and the hell of filming Mars down in Mexico, writer Dan O’Bannon on why it failed. Cinefantastique magazine (April 1991).

Interviews from Post Script: Paul Verhoeven by Chris Shea and Wade Jennings. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York and Post Script, Inc.

~ ~ ~

What was your childhood like?

I was born in ’38 in Amsterdam and, as you know, the Germans occupied Holland in ’40. So from when I was three until seven or eight, until ’45, I was living in an occupied country. The first couple of years of the occupation were pretty mild, but the last couple of years were very violent, and I was living in The Hague, which was the center of the German government and also, even more important, the launching pads of the rockets, the V1s and V2s, which were invented by Werner von Braun, who later was head of the NASA program here. He’d invented these armed rockets which were being made in Peenemünde, in Germany, then sent over to The Hague, and the launching pads were about one mile from our house. So these rockets were always sent to London. And, because of that, the English and the Americans were continuously bombing the area. That was in fact the area around our house, because they wanted to get rid of these rockets and these launching pads to prevent the rockets from going to London. So when I was living there, especially the last couple of years—it was ’44 when they started sending these rockets around—it was an extremely violent situation because of the bombs that were falling down. And as a child I think I saw so much violence there, so many dead bodies. There was a lot of blood, and, strangely enough, the whole area around our house was completely bombed out because the English squadron leader at a certain moment reversed the map in his cockpit and so they bombed the wrong area, which was a civilian area, and twenty to thirty thousand people were killed. And that was just, let’s say, one hundred yards from my house. The whole area beyond the back of the house was completely destroyed, and so that part of The Hague was completely in flames.

Did this help shape your view of violence?

It’s very astonishing when you are a child and your perception of the daily routine is dead people, violence, bombing, fire, day in, day out. I think that gives you a very strong depression which probably sinks into the subconscious later when it’s all over and the war is over and peace starts. For me, to be honest, the war was a great time. I mean I was a child and I loved it. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen the movie by John Boorman, Hope and Glory [1987]; it was exactly like that but worse. I mean that was not so violent because there was not that much happening in London. There was bombing, but not like in The Hague, which was absolutely, extremely violent. But for a child it was kind of fun. It’s amazing to say so, but that’s what I felt. It was like every day was a big adventure. Of course, if your brothers and sisters or parents are killed, that’s a different situation, but in my family nobody was killed. So as a child you don’t look much further around you—you’re not aware of the one hundred thousand Jewish people who are sent away and never come back—you realize all of that after the war, but during the war I never realized it. For me, it was like the most fantastic special effects you’ve ever seen. Every night when you look up at the sky you would see burning planes coming down. And the next day my father would bring me for a walk, about half a mile, and we would look at the plane that came down. I remember, for example, that the Germans were picking up pieces of meat, which was the English pilot, and putting them in a little box. These things are so strange, in fact, but so normal for me at the time that I think that’s responsible for a lot of the violence in my movies, my feeling that violence is normal, and that peace is anormal, that war is the natural state, and that peace is an anatural state—which of course is not true, and of course I’m not making propaganda for war—to the contrary.

Has your attitude changed?

When you get older and you have your own kids, it’s the worse thing that can happen to you. But there are things which can be learned in an intellectual way from bad or good, moral or not moral—you are a child and you are open to everything and you accept it as it is. And I think that’s basically why my defense system against violence is very limited. When I make a violent scene in a movie, all these images of the war or similar images come to my mind, and I portray them as I saw them when I was a child, without any moral standards probably, because as a child you don’t have them. You just look and see and think, “Oh, this is it.” Well, you see a hand here, and a leg there. So I think in images like those in Soldier of Orange [1979], when they’re walking in the military complex and they see part of a leg on the ground. That’s basically based on those images that I saw when this English pilot was downed. And so that’s what I feel is the ultimate background of the violence that’s in my movies. Now it’s a wonderful theory, and certainly what I’m telling you is true. I don’t know whether it’s the ultimate truth, or that I’m basically bad that I like violence in the first place. That I don’t know. But I have a little bit the feeling that to a certain degree violence is anyhow a very human situation, and that part of our brains, I would even say part of our genetic structure, part of our DNA chain, as it is genetically related to sharks and to certain apes, is probably violent in the first place. We are always trying to deny that; we always are pointing out that violence and evil are in our neighbors and not in ourselves, but basically I feel it’s in ourselves probably more than in our neighbors.

How did you get interested in film?

After the war, of course, we were liberated by the Americans, the Canadians, and the English, and the only films that were available, and the only amusement, entertainment we could get were American movies. So when I was a child of seven, eight, nine, I saw a lot of American movies, and these were probably not what you would call A-movies, they probably were B-movies. So, a lot of Westerns, action, science fiction. And as a child I thought that was great and when I got older I wanted to be a film director; very badly I wanted to be that. And I tried to get into the Institute for Cinematographic Studies in Paris, but, unfortunately, I was a month too late, so that didn’t work out. And then my father told me that I was foolish anyhow to pursue a career in filmmaking because there was no film industry in Holland in the first place. I think at that time, which was in the fifties, sixties, they made one or two movies a year, which was not extremely promising for a career. So he said I’d be much better off to go to university, and as I was pretty good in mathematics, I just took mathematics, because I thought it was interesting and elegant and that I could do it. So for six, seven years I studied mathematics, but I always felt that emotionally I was kind of warped. I think that mathematics… it’s really an aesthetic situation, a challenge to your intelligence, and even your creativity, but emotionally it’s difficult, of course, there’s not much emotion around, and also I felt that although I could do all my exams I would never be really creative at mathematics. I thought that my brains were not really prepared to defend any new interesting theories, that I would not be able to do that, that my creativity stopped after my exams. And so, during my study I started as a hobby to do filmmaking and then I got very lucky. After defending my doctorate, I was drafted into the military and they wanted to send me to the air force, to the rocket bases in Germany. I talked to the government, to the state secretarial office, and I asked to be allowed to get into the film department of the navy, and for some reason that was possible. And so for two years, I was making documentaries about the marines—pretty boring, in fact. When I came out—this was after two years, because I was drafted—I decided not to pursue any mathematics anymore, but to try to make a career in filmmaking. And so I did.

Based on the work I had done in the navy, it was not difficult to get a job in television, and from television—this was at the end of the sixties, beginning of the seventies—I moved over to feature filmmaking. At that time, between ’70 and ’80, with a lot of subsidy of the government it was not so difficult. The movies that I made together with the same producer, that was Rob Houwer, and the same screenwriter, Gerard Soeteman, and whoever has seen Soldier of Orange or The Fourth Man [1983] can see that these are the same people who are throughout all my movies. There was a group of three people who always worked together for twelve, thirteen years, and we made seven movies together, which were all, by Dutch standards, extremely successful. In fact there was no reason at all to leave Holland until the beginning of the eighties. I mean, after I made a movie in ’73 or ’74 which was called Turkish Delight and which got an Oscar nomination in Los Angeles, I was invited several times to come to the United States. Especially after I did Soldier of Orange. I got a lot of calls, even from Spielberg, who said, “I saw your movie. What are you doing in Holland? Come to the United States because it’s much better here.” And I doubted that in fact. I thought, “Well, I’m very happy in my country, why should I leave Holland? I can make the movies that I want to make, and I’m happy doing so, and there’s a lot of talent there, especially really good actors and actresses.” And it was only at the beginning of the eighties that it started to change and something very strange happened in Holland.

You have to understand the system in Holland. Films are made for 50, 60 percent with government subsidy. There are only fourteen million Dutch people, and to make a film successful, to recuperate the money you’ve put into the movie, there’s this kind of language barrier, of course, which limits your audience pretty much to these fourteen million in Holland, and a couple million in Belgium who also speak Dutch, and perhaps some people in South Africa, but that’s really limited. But altogether movies are so expensive that if you don’t have this government money, it’s impossible to make a movie. Now, in fact, this applies to the whole European Community. All European movies are made with government subsidy, because otherwise the European film industry would be completely dead. Now it’s already pretty dead, but there’s still something going on. But, without that money, it wouldn’t work any more. So the situation we have to face is to get that money. Of course you have to submit your script to a committee, and in the seventies this was a committee that was kind of right-wing, I would even say, but, being kind of right-wing, it was extremely liberal and accepted everything, more or less. If you did a good job, if you worked hard, if your films were more or less successful, you got the money for the next movie. You could go on. And at the end of the seventies, beginning of the eighties, this committee became switched politically, I would say, to the left. And strangely enough, or perhaps not strangely, this left-wing committee, like a lot of left-wing organizations, was extremely, I would say, dictatorial or another word, would be probably close to fascistic—“dogmatic” probably is a better word, not so mean—but dogmatic in the way that they wanted a movie to be relevant.

Now just entertainment was not enough, it had to be politically or sociologically or culturally relevant. And in the eyes of the committee the pictures I made in the seventies were not relevant; they were considered to be decadent and amoral, and they also thought that my pictures, especially Spetters made in 1980, were not presenting Dutch society in a good way. It was cynical, negative and downbeat. And they felt that I should not get any money any more. So at the beginning of the eighties it got very difficult to finance my movies. The last one I got financed, after a lot of rejections, was The Fourth Man, which was also, of course, considered extremely decadent because of the homosexual items that are in the movie. And that was the moment that I started to think that probably I should not stay longer in Holland. Then in the fall of ’85, I got a script from the American studio Orion called RoboCop [1987], which I did not like in the first place—I thought it was a silly American movie, and I thought that the movies I had done in Holland were on a much higher level. But my wife read it and she said, “You should reconsider this because I think you can do a nice job with it, and you want anyhow to get out of Holland, so why not take this and get out?” And so she convinced me to take the project, and in the fall of ’85 I came over to the United States and in ’86 made RoboCop, and then after that Total Recall [1990]. I’m also preparing a movie called Christ the Man which is about the last couple of years of the life of Jesus.

Which of your European films do you like the least?

I think that would be probably a film I made just before I came, before Soldier of Orange, it’s called Keetje Tippel [1975]. This is a movie that was situated at the end of the nineteenth century in Holland and Brussels—and I felt that we never were able to solve the problems of the middle part of the movie. So dramatically it fell apart halfway. I think it’s an interesting movie, with nice production design and nice parts—Rutger Hauer plays one of the parts—but basically it’s the only movie that I would like to redo, because I felt that we never got to the level that we should have got to in the first place. I still feel that the first English movie I did—in Europe, for an American company, just before RoboCop; was called Flesh + Blood, and it’s a medieval movie that is very American because it has adventure and action and was kind of romantic. Of course, it was very cynical and downbeat, but I didn’t realize that, so for the American audience it didn’t work at all—it worked OK in France, but here it didn’t work at all. I have the feeling that after that movie I would like to do another medieval movie, and try to do Flesh + Blood in a kind of an American way. In fact, we are just developing a project for Arnold Schwarzenegger which is a movie that is situated in the Crusades. So, it’s the twelfth century, 1115 or something like that. So that’s kind of a plan of mine to improve on Flesh + Blood. So these are the two movies, Keetje Tippel and Flesh + Blood, that I don’t like.

Who’s the best actor you’ve ever worked with?

The best actor would probably be Jeroen Krabbé who was the second part in Soldier of Orange and the lead in The Fourth Man. Most charismatic actor would undoubtedly be Rutger Hauer. I think Rutger has an enormous charisma and could really be a star, and, unfortunately, I think in the last couple of years he made some bad decisions in doing movies that are not worth his talent, kind of B-movies, and I think that is not improving his career very much in the United States. So, it’s really a pity because I think he’s a really interesting film actor. Jeroen Krabbé is the most talented real actor—he’s a real actor, actor—Rutger is more a film star actor.

When you approach a movie, how much does your view affect the project?

Well, that depends of course on what stage you get the script. On a lot of the scripts I did in Europe for movies like Soldier of Orange and The Fourth Man, I worked very closely with the scriptwriter [Gerard Soeteman]. Soldier of Orange is based on a book, it’s an autobiography by a Dutch war hero; in fact he is the main guy of the movie. When we bought the book, I worked through the book with my scriptwriter to find out what were the most interesting scenes and to put them together and structure them; so that would be something that I would do in very close collaboration with my scriptwriter. And then he would write a first draft, I would write a second one, he would write a third draft. So we would work very closely together. And on the movie he’d be the writer, I’d be the cowriter. In the United States the two movies that I got were finished scripts. RoboCop was around for one or two years, and nobody wanted to make it. I mean I think they approached fifteen or twenty American directors who all thought it was too silly to do. And it was not made. I thought it was too silly to do when I got the script. And it took me a long time to realize—in fact it was my wife who put me to work on it—that I could make an interesting movie out of it. So in that case the script was more or less finished. I mean, I think I improved a little bit on it, and I colored it. It’s like a black and white painting, and then you start to bring in the colors.

So that’s probably what I did in RoboCop. I pushed into the movie what I always call the “soul issue,” like Murphy looking for his lost life, or I call it his “lost paradise,” his wife and kids that are still there, that he cannot reach anymore. And you feel this kind of loss that is kind of an emotional issue in the movie I think a little bit. I pushed that, I pushed the flashback, I pushed also the spiritual levels of the movie, but basically all these possibilities were given in the script as a blueprint. There’s a long story to Total Recall. The first script was written in ’79 by Ron Shusett and Dan O’Bannon, the writers of the first Alien, and then in the ten years that passed between the first draft and when I started to work on the movie, which was ’88 or something, they wrote together with some other writers twenty-five drafts of the same screenplay. There were seven directors involved, and I think several producers and coproducers, and they started the movie several times, and it always fell apart. And so when I got the script I had twenty- five drafts to go through and to select from. Then filming you found out that first of all you have to select out what you’ve got for Arnold. There was never an Arnold Schwarzenegger role in the movie—it was about a very normal guy, physically, I mean. Arnold is very normal, but he has this kind of physique that is bigger than life, isn’t it? But this was written for somebody who looked like Woody Allen, somebody like that, and so we had to rewrite the script completely, and alter the third act completely. I think in both movies the structure and essential elements of the script were pretty much given to me, and mostly what I did was to build the building based on the blueprints, and with the European movies I think I was more part of the blueprints.

The Dutch film industry gives filmmakers about 50 percent of the money to fund the films. One might think this is helpful because you don’t have to go looking for funds, but you’ve conveyed a negative feeling that it may be otherwise. Why such hard feelings?

Well, the problem with the system like that is that it is a precensorship situation. The censorship is not after the movie is done; the censorship starts before the movie is done. You have to give your scripts to a committee, and they judge if they want to give you the money or not. And so a certain genre of scripts is not admitted, for certain reasons, and these reasons are kind of film-political, I would say. And in my case the problem was that they felt that the scripts that I was giving to them, that I wanted to be financed, they thought were too… let’s use the words “decadent” and “immoral,” and that they were portraying that society in the wrong way. And so it got to be very difficult to convince them to give me money, and every year it got more difficult. And so, what is bad about the system is that you start to censor yourself. You think, OK, I want to do this, but I won’t get that through, so let’s do this. And so, it’s really a bad situation, for a creative person, that you start to change your scripts even, to get them through this committee. And when I felt that I was close to starting to do that, then I thought it was better to get out and go to the United States. I mean, I think there are a lot of advantages to a subsidy system. This is one of the big disadvantages. If the people that are in the committee—and you’re always talking about two, three people—there’s a committee of, probably, ten people or something, but you know as well as I do, that there are always two or three people who decide what’s happening in the committee, isn’t it? Always the strong people. Now if these people dislike your work, you’re in problems. And that’s what happened to me. In ’80 or ’81, the presidency of the Dutch committee was given to a film critic who had hated my work ever since I started to do short movies in I think, ’62, when he was a critic for a newspaper—it was a short film of twenty minutes. He started already to write extremely negative things about me, and throughout the years he has done so. So when he became the president of the committee, it got very difficult, and instead of compromising I felt it was better to change gears and move to the United States.

What do you think can be done in this situation for other Dutch filmmakers?

Well, change the committee. He will get out. I mean I think this year or next year he’ll be out, and somebody else will come in, and hopefully that will be a bit more fair person. This is an unfair situation, of course. I mean, the strangest thing, of course, was that the movies that I made in Holland were all very successful. So it was not that I was spending… I mean, we got the money from the government, but we always paid the money back. Because that’s how the system works. If your film is successful, with the money that you make from the grosses you have to pay the government back, but with an additional 20 percent interest. So, if your movie is successful, the government gets more money out of you than they have put into you—because the 20 percent is in fact higher than the normal rate [of interest]. And that’s what happened to all my movies. So in fact they always got more money than they spent, and that’s why I felt it was extremely unfair that they didn’t consider that as an advantage, but that they judged it only on moral qualities and said, “Well, we won’t give you any money unless you change moods.” And so… it will change at a certain moment. I mean I feel that the situation in Holland… I mean now after so many years, when I came back with Total Recall this year I felt that the whole situation in Holland had really changed a lot. There were always a lot of problems with my work in Holland and a lot of controversy, but with Total Recall they all seemed to… be very positive. So Total Recall somehow changed the perception of my work in Holland again. Made it… Strange, but it happened—especially when you consider that Total Recall is [a] pretty violent movie—it was still strange that there was a very positive reaction from all the reviewers. When I did Spetters in 1980, one of the four last movies I did in Holland, it had the worst reviews, the most negative reviews as I can imagine, all over the country, in every paper, in every television, every radio program, it was really… I mean it was the worst. And really there was a perception that my work was perverted, decadent, and should not be subsidized anymore. This was generally in the papers, and now—this is ’80—so ten years later now with Total Recall there was a real change, that people suddenly thought, “Oh, it’s not so bad… it’s interesting,” or whatever. So… when I came there it was like [a] prophet coming back to his own country a little bit, or the lost son or like that… It was a very positive atmosphere. So I think things are changing, but it took ten years.

What similarities do you see between the films you made in Holland and the ones you made in the U. S.?

I think my movies are mostly well thought out, and I spend a lot of time in preproduction to make the movies as compressed and as fast as possible. Of course, the themes of the movies that I did in Europe are so different from the themes that I did here that it’s difficult—even for a lot of people probably amazing—after seeing the American movies to go back to the Dutch ones and look at them. It’s kind of amazing that the same person did them. I think there is always some things that will stay personal like some feeling for humor, if it’s normal humor or a kind of black humor, and interest in people, but… it’s very difficult for the person himself who makes these movies to see the similarities really. I mean, basically I think there’s a big difference between RoboCop and Total Recall on one side and the Dutch ones on the other side. I see more dissimilarity, in the way that I think all my European work was based on reality. I mean, Soldier of Orange was an autobiographical book, Keetje Tippel was autobiographical, Turkish Delight was, Spetters was based on newspaper articles and all taken from magazines—all real things. Even The Fourth Man, even though it looks like a fantasy, was 80 percent an autobiographical novel. And so everything was based on reality, and when I went to the United States RoboCop and Total Recall, of course, are based on nonreality. There is nothing real there—it’s all fantasy. Nobody like RoboCop ever lived and certainly the situation in saving the planet of Mars is fantasy. So I think there’s a big difference in approach. I feel a little bit like… when I went to the United States and started to do these movies, for certain reasons, that I was going back to my childhood.

I always liked special-effect movies when I was a kid. The War of the Worlds [1953], produced by George Pal, was one of my favorite movies when I was twelve or something like that. And I even, when I was younger, I started to make a comic book based on that. I mean I loved that stuff, but then I started to work in Europe as a film director myself and I went much more to a realistic approach. And it’s like I forgot about comic books and science fiction and all these childhood dreams that I had. And, strangely enough, when I came to the United States, that came back. It was offered to me, and I jumped at the occasion because probably I had repressed it for twelve or fifteen years. I mean, I’ve always been working with the same scriptwriter in Holland, Gerard Soeteman, and he’s an historian and an extremely realistic person. And he dislikes fantasy, he dislikes science fiction; he thinks it’s all nonsense, and he doesn’t want to deal with it. Now, if you work together with somebody like that, then what you do are the things that you have in common; you don’t do the things that are different. So what was activated when I was working with him was my sense of reality and realism, and I think when I lost that connection with him, when I went to the United States and started to work with other people, other scriptwriters, then these other things came up. And I think at a certain moment probably I’ll switch back to reality, and I think—hopefully when I can continue to work here and everything goes well—I’m sure that in the next five years I’ll be more into realism, back to realism, than I’m now. I think even Basic Instinct [1992] is now already a much more normal movie than Total Recall.

Why did Orion pick you to direct RoboCop? What do you have over other directors?

I didn’t have anything over other directors. It was just that nobody else wanted to do it. It’s absolutely true, and I’m not making a joke. I know there were about ten or twelve directors invited by Orion to do RoboCop before they asked me, and some really well-known directors like Jonathan Kaplan, who did, for example, The Accused [1988]. And Jonathan worked on the movie for five, six months, and then… by coincidence he got the script of Project X [1968] and he preferred that to RoboCop, so he dropped RoboCop and went into another movie. And it happened several times during one and a half, two years that they started with a director and then the director just dropped out. When I came to the movie, when they sent me the script, the project was really dead. It was just that Jon Davison, the producer, who knew my European work, thought, “Well, perhaps this Dutch director wants to do it, because we cannot find an American one.” That was basically the whole idea. And it was not that I was a favorite person there, it was just the last chance, probably.

How would you compare RoboCop and Total Recall to your earlier work?

Deliberately, I think, these two movies are pretty far away from the work I did in Holland. They are action oriented, they’re very much science fiction, there’s not that much dialogue, and they’re probably less personal. I realized that so many European directors have failed in the United States, they have tried for one or two years to do personal movies in the United States, and then of course when they are not so successful, they have to go back. I felt that it would take me about five, six years to learn about the United States, to learn the language better, to learn the cultural situation, to find out what American audiences are like, not only what they prefer, but what their perception of movies really is. And so I set out to do two movies, RoboCop and Total Recall, that would not have too much dialogue. I just tried to avoid any script that was based on dialogue, because, you can guess, I mean, it was certainly not my favorite thing, dialogue. It cannot be your favorite thing when you go to a country where you know the language only partially. And so I avoided that and concentrated on films that have strong visual impact. And because I was interested in science fiction and special effects, with my background in mathematics and physics, I thought it was interesting to learn how to do special-effect movies. And so that’s what I did for the last five years, and it’s only now in ’90–’91 that I’m slowly starting out to go in different directions and trying to make movies that are more based on normal things than on special effects. In fact, Basic Instinct, with Michael Douglas, I would say is a kind of erotic thriller and is much more based on dialogue than anything I’ve ever done before.

Why didn’t you direct RoboCop 2?

Because I thought it was boring to do a sequel. That’s basically all it was about. It’s very difficult to make a sequel better than the first one. If there’s a concept for several sequels before you do the first one, like Star Wars has a concept of Numbers 4, 5, and 6, I think you can make a good sequel, but if you just base the sequel on the fact that the first one was successful, I think it’s pretty bad. And anyhow I just was afraid that I would be bored when I was shooting it. So I felt that it would be more interesting to do something not completely different, but really different, like Total Recall, and so that’s why I didn’t do it. It’s very difficult to improve on a sequel; I think the best sequels are done by Lucas and Spielberg, and as you know, Spielberg, for example, is clever enough not to do one sequel after the other. After Indiana Jones, he did other movies in between and then he did Indiana Jones 2. And when they asked me to do RoboCop 2, that was immediately after RoboCop, so it was like only one movie. I think that’s killing all your creativity, isn’t it? And anyway, these movies are so difficult, and you’re so exhausted after you do a movie like that with all these special effects and all the action, that I think it’s really bad to do one after the other. It’s like selling cookies. The cookies go very well and everybody likes these cookies, so why shouldn’t you go on for the next ten years selling these cookies? It makes sense economically, but artistically, from the creative point of view, it doesn’t make any sense at all. So basically I would say, “No, I wouldn’t do a sequel” and I have never done so. I rejected RoboCop 2, and the plans for Total Recall 2, which basically are there and I will certainly not follow up on it unless I’m in big problems probably. Sometimes it’s a good way to resurge your career.

How important is the score in your movies?

Very. I spend a lot of time with the composer to go through all the different cues and find the most effective music. Now of course I’m not writing the music, but you can help the composer a lot by saying, “OK, I want a rhythmic situation here, then I want to be changing the rhythm to a different mood.” When you work very closely with the composer, I think you can really improve the score. And especially with movies like RoboCop and Total Recall, which are all action, I think a good score helps to make it more pleasant for the audience to look at the movie. So I think it’s very important. And I like music. I like it, basically because when I read a novel or look at films or whatever I always have the feeling that I have to see if I can do something with it.

What are the technical aspects of your directing style?

Well, that’s difficult, because that would involve probably a couple of days to tell you. But with movies like Total Recall and RoboCop, these movies are very technical, and so you have to prepare them very carefully. And every shot of a movie like that is storyboarded, and all these storyboards go to the different departments, and everybody studies them, comes up with their own solutions, comes back to me, and so basically what you are, much more I say than a painter, you’re much more a general in the middle of a very complex logistics system. And of course the problem is that you could lose any real creativity, because it’s more logistics sometimes than filmmaking. And the challenge always with these big movies is to be aware of all the technical problems, but not to think that they are the most important. And I think that’s basically what I tried to do in both movies, which was a little bit easier in RoboCop, because it was technically an easier movie than Total Recall. After doing these two movies I wanted to do something with actors again. I mean, not that these aren’t with actors, but there’s so much more emphasis on other things than on the acting in Total Recall or RoboCop that I thought that I should go back to more normal situations, where the actors are more important than the special effects or the action. So, Basic Instinct at least will be a movie where the actors are important, and the plot is important, but the action is really minor, and there are no special effects.

You’ve done two movies, and they’ve had to be cut because of the ratings system in America. How do you feel about that and about your artistic expression and how that affects your use of film?

Well, in both cases, especially in the case of RoboCop, but also with Total Recall, when we gave the film to the MPAA, the ratings system board, we got an X rating. And, in fact, after cutting RoboCop seven times, we got seven times an X rating. And it was only the eighth time that we got the R. It was easier on Total Recall. I think we had to go there twice to get an R rating. The committee was much more appreciative. They liked it much more than RoboCop. They said that they liked the movie, even that they were pleased, but that they felt it was little bit too strong, and please could I soften or tone down a couple of scenes. Then they said, “This scene, this scene, and that scene.” And so we did and then we presented the changes and they said, “Oh, it’s fine.” It was very easy. It’s kind of disturbing, I think. I would say that every form of censorship is wrong and that people should always be able to see whatever they want, and, if the rating leads to a kind of censorship, then it’s a problem. Now, there are two kinds of censorship. There is a real censorship, like they still probably have in Russia, and there’s a kind of hidden censorship, like we have in the United States. If the censor board gives you an X, that is called a “rating,” but in fact it’s a censorship situation, because they know that with the X rating you cannot release the movie.

So, in fact, they prevent you from releasing the movie by giving you an X, which is a hidden censorship situation. And I found it extremely unpleasant, when I was doing especially RoboCop, that I had to change it too many times and reduce the impact of the movie. Now, I don’t know about what’s wrong or right there by making it so violent in the first place that I had to tone it down. I felt that the movie as I cut it the first time was more of a comic book, had more of the comic-book, over-the-top violence feelings than what I ended up with after all the editing. With the editing it felt more real and more violent to me than the original—which was so completely over-the-top that it was just funny. Well, I thought funny. But the rating board thought differently. Now I think adding NC-17 to the rating is probably a step forward, unless there are so many minority groups that start to protest—mostly from churches, of course—against the NC-17 that the NC-17 becomes like an X rating, and then nothing’s improved, really. I think there’s a clear difference between a pornographic movie and a nonpornographic movie. I don’t think that Henry & June [1990] is a pornographic movie. It’s what you would call an erotic movie, whether you like it or not. And it’s very clear what a pornographic movie is. But if people start to see NC-17 as a disguised X rating, then the networks won’t give you the opportunity anymore to show your spots because they will say it’s a disguised X. It’s moving a little bit in that direction now. The NC-17 opened it up, but now, of course, the people that make porno movies are trying to get into the NC-17. And if they get in, then NC-17 becomes the same as the original X, and then television and newspapers will say, “We won’t accept the spots or the ads anymore.” So that’s basically what’s happening now. And it will be interesting to see if NC-17 will be accepted by the majority of the media or not.

How do you feel about the large amounts of violence that have been in a lot of the films lately?

I like it.

Do you feel that it affects the audience in a negative way… the children who see it?

Naw.

Or the youth who see it?

No. No, I don’t think so. I’ve never felt that. I mean I’ve seen a lot of violent movies, and I never came out of a movie thinking that I should do something violent, really. Basically I don’t think that people are violent because they see a movie; I think people are violent in the first place. I think people have a violent genetic structure, and I think that if you look at the bad things that happened in the world, with or without movies, the bad things that happened, the evil things that happened in Europe in the thirties, forties, I don’t think that any movie pushed Hitler to do the things he did. I don’t think that bad things come out of movies. I think movies are just a reflection of what society is about. There are two theories, of course, and what you’re saying is the first theory, that violence in movies adds violence to society. The other theory is, of course, that violence in movies reduces violence in society, that people get enough violence in the theater that they are not violent anymore when they get out. I don’t believe both theories, in fact. I think it doesn’t affect society at all, I think society is violent and it always will be. But there was an interesting article in the paper a couple of weeks ago, where they did an experiment in a Miami prison where they showed for some time very extremely violent movies like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre [1974], and other violent movies. And what they could measure indicated that the violence among the prisoners after seeing the movie was reduced. It’s a nice example in favor of saying, “Oh, the more violent the movie is, the better.” But basically I would stick to what I said before—I don’t believe both theories and that I think violence in movies has nothing to do with violence in society.

What was the total budget or cost on Total Recall?

Well, we started out with a budget of $43 million, and then I went over bud- get, so it added up to $57 or $58 million, I think—which is an enormous amount of money, especially when you realize that then we have to add about $20 million for publicity, for spots on television and other promotional items, and there’s another $5 million for prints to send to the theaters, of course, and there’s probably another $8–$10 million for losing the interest during the couple of years the film is in production. Altogether the real costs are around $90 million, I would say. It’s amazing, but it still works, you know. Because besides what the film will make in the United States, around the world it will earn another $120–$130 million, so altogether the grosses of the movie will be around $240–250 million. And half of that, a little bit less than that, let’s say, would be coming back to the studio, which is around, say, $110–120 million. So basically you make such small profits on the theatrical release here and overseas that, of course, it’s not worth doing, because that’s too small a profit, isn’t it?—about $10–20 million, which is an enormous risk on a movie of $90 million. But where they really make the profits nowadays is in the video sales and on television, and that’s basically why you can do a movie like that, because then there is an additional $40 million coming back to the company, immediately, after, let’s say, one or two years, and then for the next ten years, there’s every year $5 or $10 million dribbling in.

So, although it seems to be outrageous to make a movie for $60 million, and ultimately for $90 million, from an economic point of view, it’s still a healthy situation. Whether it’s healthy from an artistic point of view, that’s probably up to you to decide. But commercially, economically, it’s “Oh—if the film works well, of course. If the film doesn’t work, then…” Somebody asked me how I felt about Ghost [1990] doing better than Total Recall. The grosses of Ghost will end up close to $290–300 million, which is about $60–$70 million more than Total Recall. Now when you realize that the movie Ghost was made probably for—say, $25–$30 million—half the price of Total Recall, of course it’s clear that a movie like Ghost is to the people that make it, still talking economically, more interesting than Total Recall. On the other hand, nobody in Hollywood realized when Ghost was finished that it would do something like that. They released it in a limited number of prints—about 700 or 800—which is an indication of the belief in the movie. If you compare that with movies like Total Recall or others like 48 Hours 2, which are released in 2,300 prints, that’s where you see what the industry is really expecting was going to happen. And then they found out that Ghost was doing extremely well and they added prints and then more prints. But then it’s difficult to foresee a success like Ghost or Pretty Woman [1990], even. It’s easier to foresee and to structure a film like Total Recall. And that’s why we still make these movies, and if a movie does well, like Die Hard 2 [1990] or like Total Recall, then it’s a good investment. It’s not the sensational investment that you get out of Ghost or Pretty Woman, but Pretty Woman and Ghost are really things that nobody could foresee.

What’s it like to work with a star like Arnold Schwarzenegger?

Extremely pleasant. He’s a very charming man, in fact, and he’s very supportive to the director. So, for example, when I went over budget, and I had the studio then fly over (we were shooting in Mexico City), and they come over and they start to be mean to you, because they want you not to go over budget. I was already over budget probably by five or six million by then, and this was halfway into production, so they were certainly foreseeing that there would be another five million, and that’s what happened, of course. And so, they wanted to eliminate scenes. If you don’t fire the director, then the first thing you’re going to do is to try to cut the script and take pages out that are expensive. And what happened, when they wanted me to do so? My power is not the power of Arnold Schwarzenegger—and that’s not only physically. In a film-political way, Arnold’s wish will normally be fulfilled in Los Angeles. And Arnold wished that the pages would not be taken out of the script. In fact he had such in his contract, and he used his influence—you could also say his power—to “convince,” if you want to use that euphemism, the studio that we should do the movie as it was written. So we immediately shot the movie as it was done by the scriptwriters. I think if Arnold really likes the director and he feels that the movie is moving in a good direction, that it’s a strong movie, then he is extremely supportive, and then he’s a nice fellow to have around. I’m always pretty neurotic when I’m shooting a movie—I’m normal now. In preproduction and postproduction, I’m kind of normal, but when I’m shooting a movie, I get very tense because it’s so difficult. And Arnold is a very easygoing, confident man, and, when he gets to the set, it gets really very pleasant. So it was absolutely fantastic to work with Arnold and I would any time do it again.

Can you see any new concepts coming out of Recall that would make you want to do a sequel to that?

Well, I wouldn’t do it, but they are vaguely thinking about it. It will be very difficult to achieve, I think, because it’s such a special theme, and I think if you copy it then it will be kind of peculiar and repetitive. Then you might be dreaming that you’re dreaming that you’re dreaming, or something like that, and now it’s only dreaming that you’re dreaming. So, I think it will be tough to do a sequel, and I hope they don’t. I mean it wouldn’t make sense to me to base a sequel on that. Better to do something original.

Within the past couple of years there has been a tendency in the science fiction-action-adventure genre, with movies like Star Trek V [1989] and RoboCop 2, to lose total control of the film’s ending. I understand that there were a lot of problems with the third act of Total Recall.

There were problems with the third act in all twenty-five drafts, and we tried to solve the problem as much as we could. Basically the problem of the film always was that you have a very interesting mental theme: a man finds out that he has lost his identity, that he has, let’s say, the wrong memory. And there are a lot of interesting flipping-around things in the movie. The last good one in the original script is probably when this man [Edgemar], his doctor, comes into the room and tells him that he is not there, that he’s still dreaming, and he’s trying to prove to him that he’s dreaming. And then from there on in all these drafts what always happened was that for the last forty minutes of the movie it was just one long action stuff—it was just Arnold trying to get to the nuclear reactor, or whatever it was in all these drafts, and pushing a button, and making a lot of noise. And it was very difficult to solve that problem, because basically it was difficult to find another mind-flip to add to the third act so that in the third act you at least also have the mind stuff. And what we added—it was added by scriptwriter Gary Goldman—was the situation where in the third act you find out that the person that you thought was a good guy, Hauser, who gives him all the instructions and who was his former personality, is bad, and that’s the last thing that we added as a mind-flip. After that there was still another fifteen to twenty minutes to go which is then full action. If a film has a lot of good twists, then it’s difficult to do without them for the last fifteen to twenty minutes and only to base yourself on action or adventure, whatever. So that was basically what I would say was the problem, and we tried to solve it as well as possible.

How does your background in math and physics help your filmmaking?

Well, not really very much. I think every university study prepares you very well for anything in life but then being a taxi driver in New York would prepare you very well for a career as a director. Probably better, because you would know more about life. I think what university study does is prepare your brains; it programs your brains. It’s like computing your brains to analyze problems and to solve them, and whether you do mathematics or psychology or whatever, I think that basically it’s always the same. I think the only advantage I have from my math or physics, probably, because I did the mathematics of physics, … is that when I do special effects I can understand what a mirror image is, or something like that. But every film director without any mathematical knowledge can be an expert in visual effects if he takes the time. Spielberg or Lucas do not have a degree in mathematics at all and they are probably the best at special effects I have ever seen, better than I am, even more inventive there than I am. I think what I did in Total Recall was not so much going into new ways. I think Lucas, when he did Star Wars [1977], invented a lot of things which were new, especially the cameras that are moved by computer. What you normally have in special effects is that the scene is shot several times: it’s one shot for the background, it’s one shot for the foreground, and for the middle ground, then there are the starfields that have to be brought in, some other spaceships have to be brought in, and they do that in several passes, so that every time you shoot only one element.

What Lucas invented, in fact, that was the big invention, was that they did that of course before in a lot of movies, but they never did it with a moving camera. So if you look at Lucas’s film you see [that] when the starships are going into the frame and things are happening, you always see the camera moving, the ships go to the side and the ships come around from the side. This is definite camera movement, and to do that if you have several passes means of course that that camera has to do that movement exactly the same every time. And the big invention that Lucas brought to filmmaking is that he established that computer system which is regulating the camera movement. So you see that there is a registration of the camera movement by the computer and then if that’s in the computer, then you press the button and the computer repeats the movement always the same. And I think that’s probably the only big change in special effect movies in the last twenty years. And I think I have not produced anything new like that in Total Recall. Total Recall is really using all the techniques that were available that were invented by Spielberg and Lucas and other people and using those probably in extremes, but it’s still the same technique. So, I don’t know, my mathematics seems to be lost.

Why did you use Dream Quest special effects instead of ILM in Total Recall?

Money. That’s what they said. What you normally do—there are four or five of these factories, production houses, that do these special effects. There are three or four in Los Angeles and one big one, the Lucas one, in San Francisco. So you give them the script and you ask them what their budget is on the special effects. And apparently the ILM budget was a couple of hundred thousand dollars more expensive than the Dream Quest one. And that’s why my producers decided to go to Dream Quest. Ultimately, of course, the budget for the special effects was supposed to be $4.2 million. And Dream Quest was 4.32 and ILM was 4.5. I wanted to go to ILM, I pushed everybody to do that but I was overruled and the producers decided to go to Dream Quest. Of course when the film was finished we had to pay 8 million—so it was probably not the best decision of the world. I would have preferred to go to ILM because they are the best, they have the best people, the most experienced; also when I got there I felt very supported by them. Not that the results of Dream Quest were bad; the results were great, but the money was also great. It was very expensive.

Is Total Recall real or a dream?

Both. To be honest, that’s what I want. I made the movie in a way that it would be true on both levels, and I spent a lot of time to get that. If you want a scientific explanation, you know, of course, in quantum mechanics there is a very interesting principle, the principle of uncertainty, Heisenberg’s principle. If you have a moving object and if you try to measure the place of the object and the velocity of the object at the same time, the more precisely you measure velocity the less precise place gets. So that’s the principle. That means, of course, that there are different realities possible at the same moment. What I wanted to do in Total Recall is to do a movie where both levels are true. I mean for me, of course, the film anyhow has to do with two realities, one being the reality of going as a secret agent to Mars and discovering that there is a problem, and solving the problem, which is starting the nuclear reactor and helping the guerrillas and destroying Cohaagen. The second level of the movie, of course, is that from the moment that he goes into the Rekall chair till the end it’s a dream, and I tried to make that second level work throughout the whole movie. So there’s the dream level which starts when he gets into the chair and the thing is in his neck, and that would go throughout the whole movie, so in the next scene where they say, “Oh, there’s a problem, there’s a big glitch here,” that would be already the dream, of course. That’s where the dream starts. And the next scene where they are fighting and stuff would be part of his dream, convincing him that it is real, because there is a glitch, but that would be part of the program. It would be built into the program to make him accept the fact that it’s real, but it’s a dream.

If you look at the movie, if you haven’t seen it, or for the second time, you’ll see that the whole program that’s set up at the beginning when he goes to the Rekall office and he talks to this guy who sells him the program on Mars, you’ll see that he gets everything that he wants: he gets the trip to Mars, he gets the girl, the exotic girl, he kills the bad guys, and he saves the entire planet. That’s what he does. And that’s basically the dream. Even halfway through the movie, you may remember, this other guy comes in, Dr. Edgemar, and tells him that he’s in a dream, that he’s still in the Rekall chair, and then Arnold says, “If I’m there, I can kill you.” And he puts a gun to his head and the guy says, “Sure, no problem for me, big problem for you, because you will be psychotic from now on because the walls of reality will fall apart. One moment you will be the savior of the rebel cause, the next moment you’ll be Cohaagen’s bosom buddy, but in the end—you will even have these strange fantasies about alien civilizations—but at the end you will be lobotomized.” And then if you see the movie, you realize that all these things happen. I mean he is lobotomized at the end. That’s why at the last shot, when they are so happy and kissing each other, it slowly fades to white, which for me meant, “OK, there he goes. That’s the end—that’s the dream—they lobotomized him.” And all the other things happened—he finds the alien civilization, he rescues the planet, he finds the good girl, he kills the bad guys—but it’s a dream. Now, of course you can see it as a reality, too. So at the end of the movie, going to white means either it’s a happy ending or he loses his brains, which is a probably also a happy ending, I don’t know. That was basically what I wanted: that at the end there would be two possibilities, and they would be both true. For me they are both true—it’s not either one or the other. It’s not that either it’s a dream or it is a reality. It is a dream and it is a reality. And I think they’re both there.

What made you choose Basic Instinct?

Well, first of all, I wanted to do something different. I wanted to move away from the action-science fiction genre, because you get so typecast. Everybody thinks that the only thing you can do is science fiction-action stuff. And I think I can do something different, and I did a lot of different things in Europe, but then in Los Angeles after doing RoboCop all the scripts I got were kind of about robots and action and all that. Total Recall was a little bit in the same line, but I did it because it was the best script that I could really find after reading 150 to 200 other scripts. I wanted to do something light and something normal without science fiction, without special effects. I couldn’t find it. And then Total Recall was the best thing I could get in my hands, and so, after half a year of looking, I said, “OK, I don’t want to do special effects, but in this case I like the script so much. Let’s do it again.” So now, after Total Recall, I really want to move away from science fiction-action, and Basic Instinct is much more a Hitchcockian thriller. It’s much more about people, in a kind of a tense situation, where a couple of murders are committed, and there are two or three possible suspects—they are all women, in fact. And the story is about Michael Douglas, who is the main character, a cop, a homicide cop, and he’s investigating this murder stuff, and in the meantime he falls in love with a woman who could be the murderess. So that’s the story a little bit.

Who are some of your favorite directors?

The directors I really studied the most to learn from were Hitchcock and David Lean. I think David Lean is probably one of my favorite directors. I think movies like Lawrence of Arabia [1962] and even Dr. Zhivago [1965] or The Bridge on the River Kwai [1957] are some of the most interesting examples of what film could be, and seldom is anymore. That it is at least touching something which we called some time ago “art.” And I don’t think it happens very often anymore that films make you feel that film could be a form of art. I mean it has been so much reduced to entertainment alone, that it’s difficult to find films of the richness and the inventivity and strengths of Lawrence of Arabia. David Lean I think is one of the real masters of filmmaking, like Kurosawa is, and some others. And I think Hitchcock was extremely important for me because he is such a professional. I think every movie of Hitchcock you can study forever and you will always find new things that you can use yourself. I mean, if you know the work of Hitchcock very well, and you look at Total Recall, you will see that some of the, let’s say, normal scenes in Total Recall—not the action stuff, but the scenes where Dr. Edgemar’s coming into the room, where he’s telling him that he is living in a dream—are shot copying more or less—well, not copying, hopefully not copying—but are at least heavily influenced by the work of Hitchcock, by the way he staged his scenes, by the way he works his cameras and that stuff. And even nowadays I’m still studying a lot of contemporary directors, mostly for technical elements. When I was preparing RoboCop, I studied The Terminator [1984] over and over again to see how Cameron was doing his shots. And when I did Total Recall, I studied his movie Aliens [1986], the second one, which has a lot of elements that are kind of identical with sucking air and all that stuff, so I studied the movie shot-pro-shot in slow motion to see what tricks he did and to copy them.

When are you going to make a comedy?