April 17, 2023

By Tim Pelan

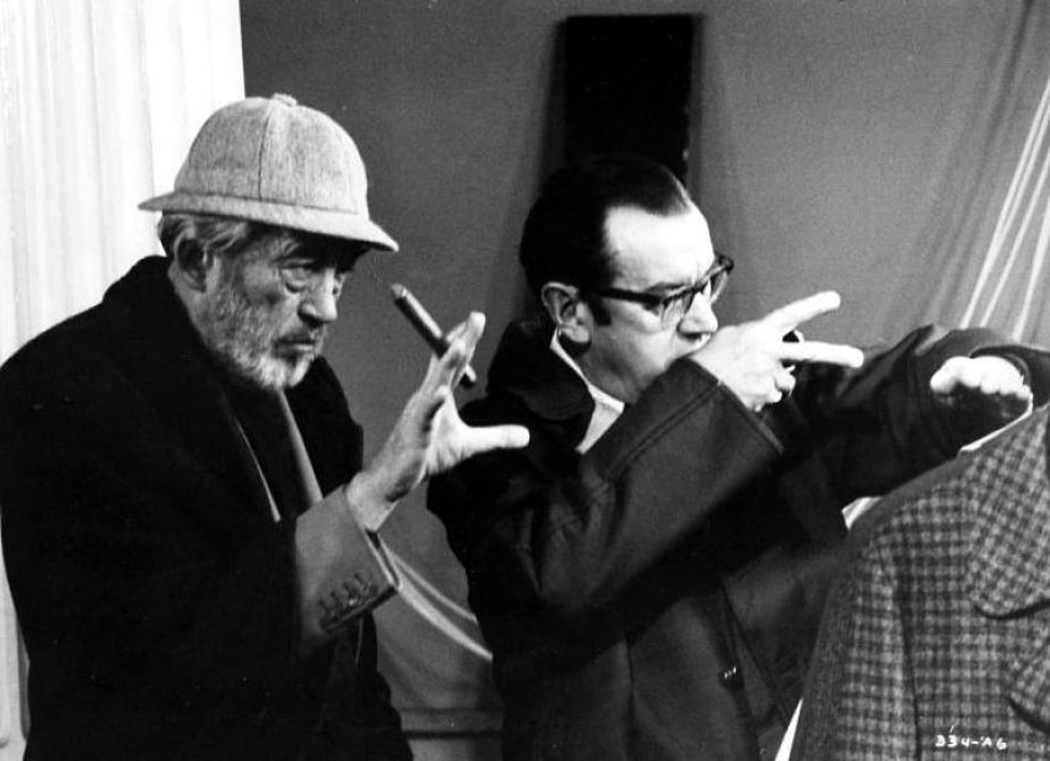

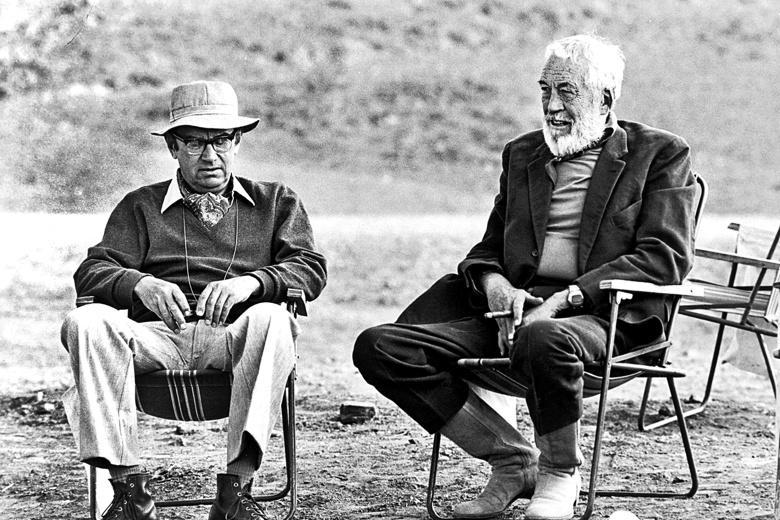

I think one of the reasons we immediately got close was the first thing he felt from me was enormous respect for him as an actor. When you look at the Bond characterization, everybody says, ‘Oh, well he’s just charming.’ Well shit, that’s like saying Cary Grant was just charming. There is more acting skill in playing that kind of character. What he’s doing, stylistically, is playing high comedy. And that is extremely difficult to do, which is why there are so few of those actors, so few Cary Grants and Sean Connerys. But it’s acting, don’t kid yourself. And right away on The Hill, the very fact that I cast him in it meant something. And he was so thrilled to be taken that seriously for that kind of a drama. —Sidney Lumet

When Sir Sean Connery passed away on 31 October 2020, it became known that he had sadly struggled for some time with dementia. Yet as old friends and family rallied around, he would have flashes of insight to his illustrious, iconic career on screen. Fellow Scot and long-time pal Sir Jackie Stewart, a legend himself in the world of motor racing, recalled in Connery’s obituary that it was one of the actor’s favourite yet least-known films that he desired to watch again with his pal. “He told me that he wanted to watch Sidney Lumet’s The Hill, his favourite film in which he’d acted. That role meant more to him than all the Bonds. The next day, he asked me again if I’d like to see it as if he’d never asked me before. And so, we did.” The Hill has long been a critic’s darling, but neglected on streaming services and so far ignored by boutique physical media formats, available only sporadically on vanilla DVD releases. In Woody Allen’s 2007 biography written by Eric Lax titled: Conversations with Woody Allen: His Films, the Movies, and Moviemaking the director says of The Hill: “For some reason, American audiences do not really know the film The Hill. In a filmography like Sidney Lumet’s, which includes many remarkable works, The Hill is perhaps the most successful. I certainly consider it one of the greatest American films. The making of this captivating story is perfect, from the actors’ impeccable performances to the inspired camera movements. It’s an immediate and total experience. Every time I see it I am surprised that such a wonderful film can pass unnoticed and fall into oblivion, which is what has happened.”

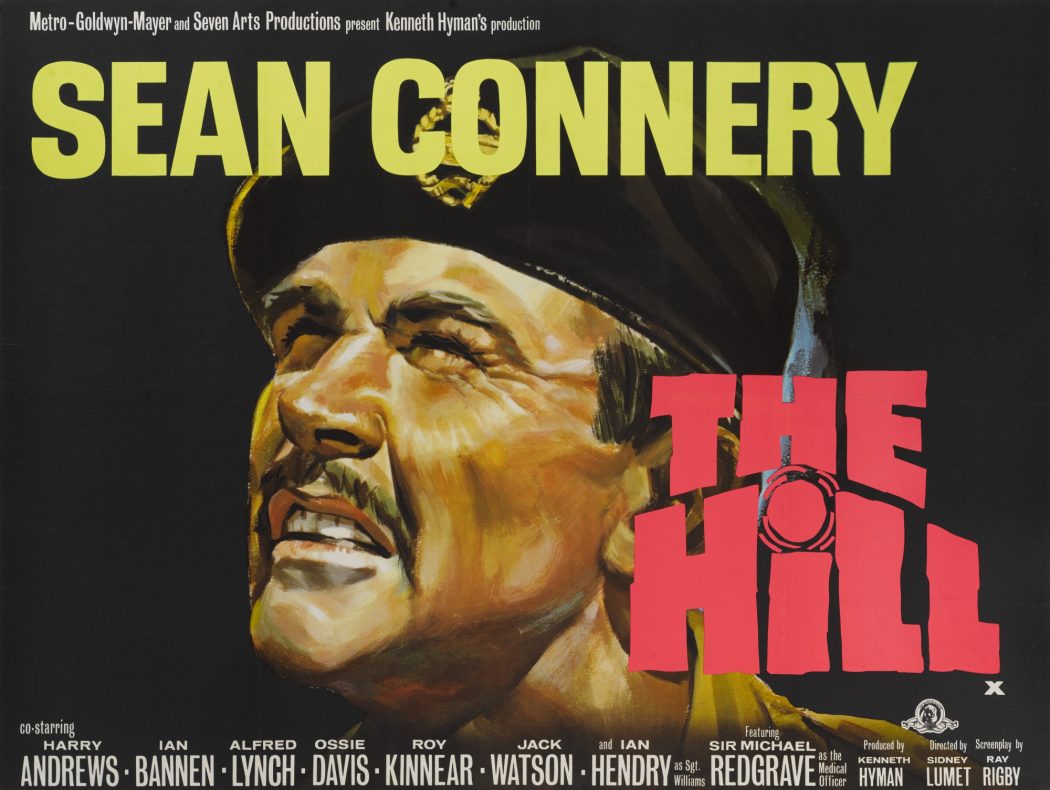

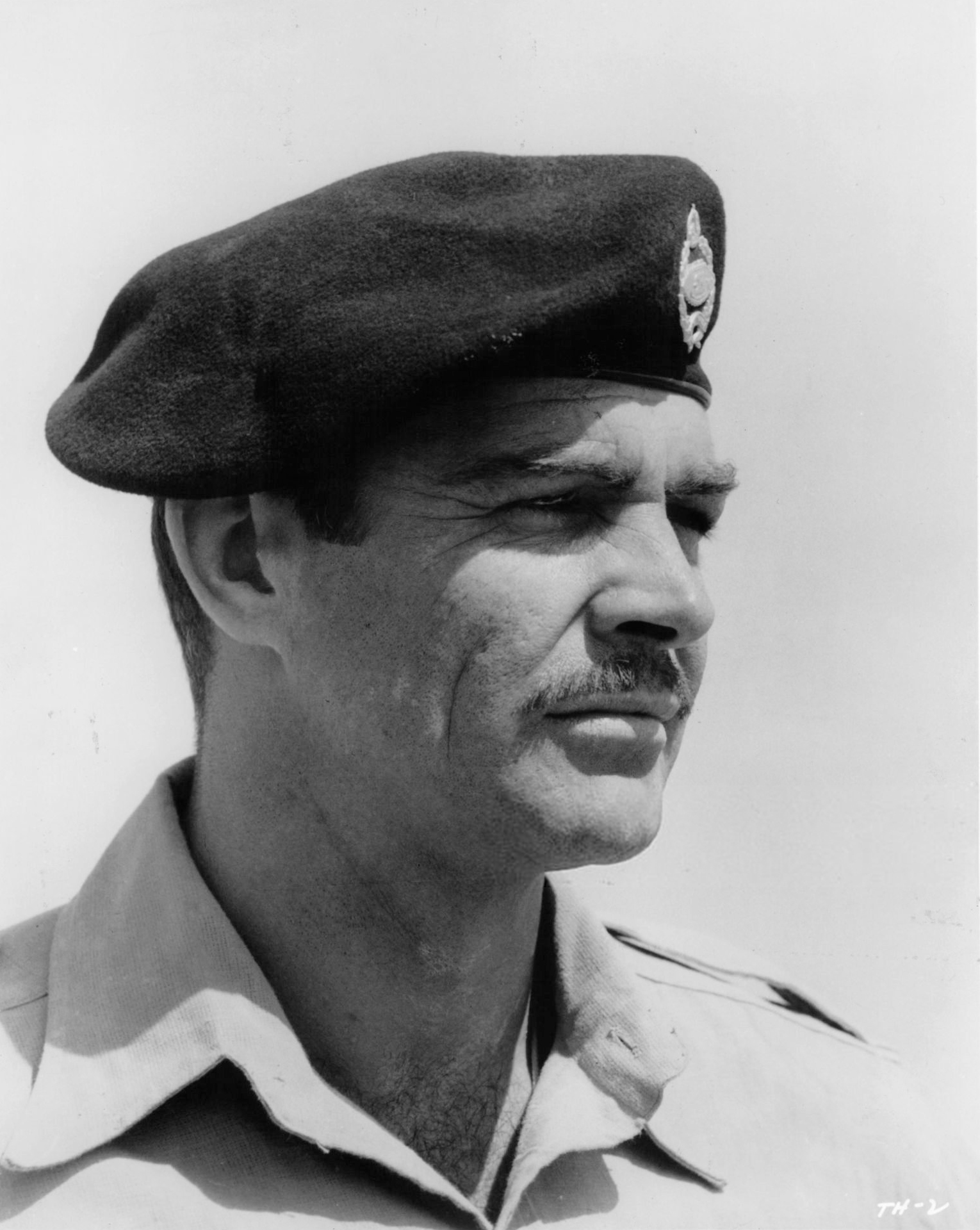

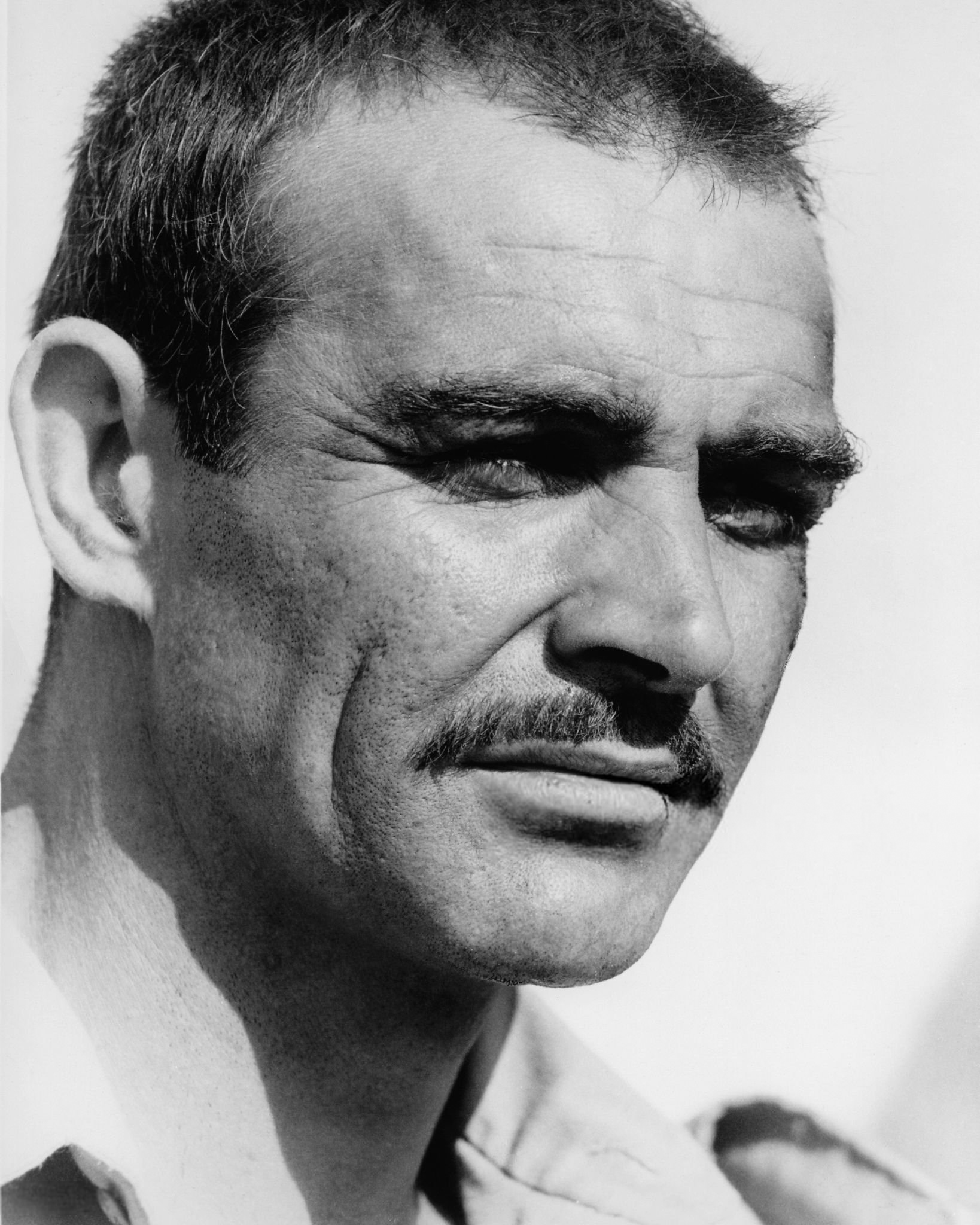

In this favourite film of Connery’s, written by Ray Rigby and based on a play by R. S. Allen, British army prisoners in WWII North Africa are, for a range of King’s Regulations infractions, subjected to the pitiless trials of Sisyphus on the eponymous “Hill,” the punishing, punishment centre piece of the prison, or “glasshouse,” in informal military parlance. Filmed in 1965 in the midst of his James Bondage, Connery knew a breakout role when he saw one. He ostensibly plays the lead, or, at least catalyst for the struggle that will erupt here, as blind devotion to the breaking and building up of men for the front threatens to tip into sadism and abuse of the unbending system. He plays Trooper Joe Roberts, a Sgt. Major broken down the ranks for refusing a suicidal order to take his men forward into near-certain death. This sets him apart as a special case when he arrives with four others to the glasshouse. RSM Wilson (Harry Andrews, brilliant) entrusts newly arrived Staff Sgt. Williams (a nasty, sly performance from Ian Hendry) to discipline and drill them. Between them, appealing vainly to Wilson’s better nature is humanitarian time server, Staff Sgt. Harris (Ian Bannen).

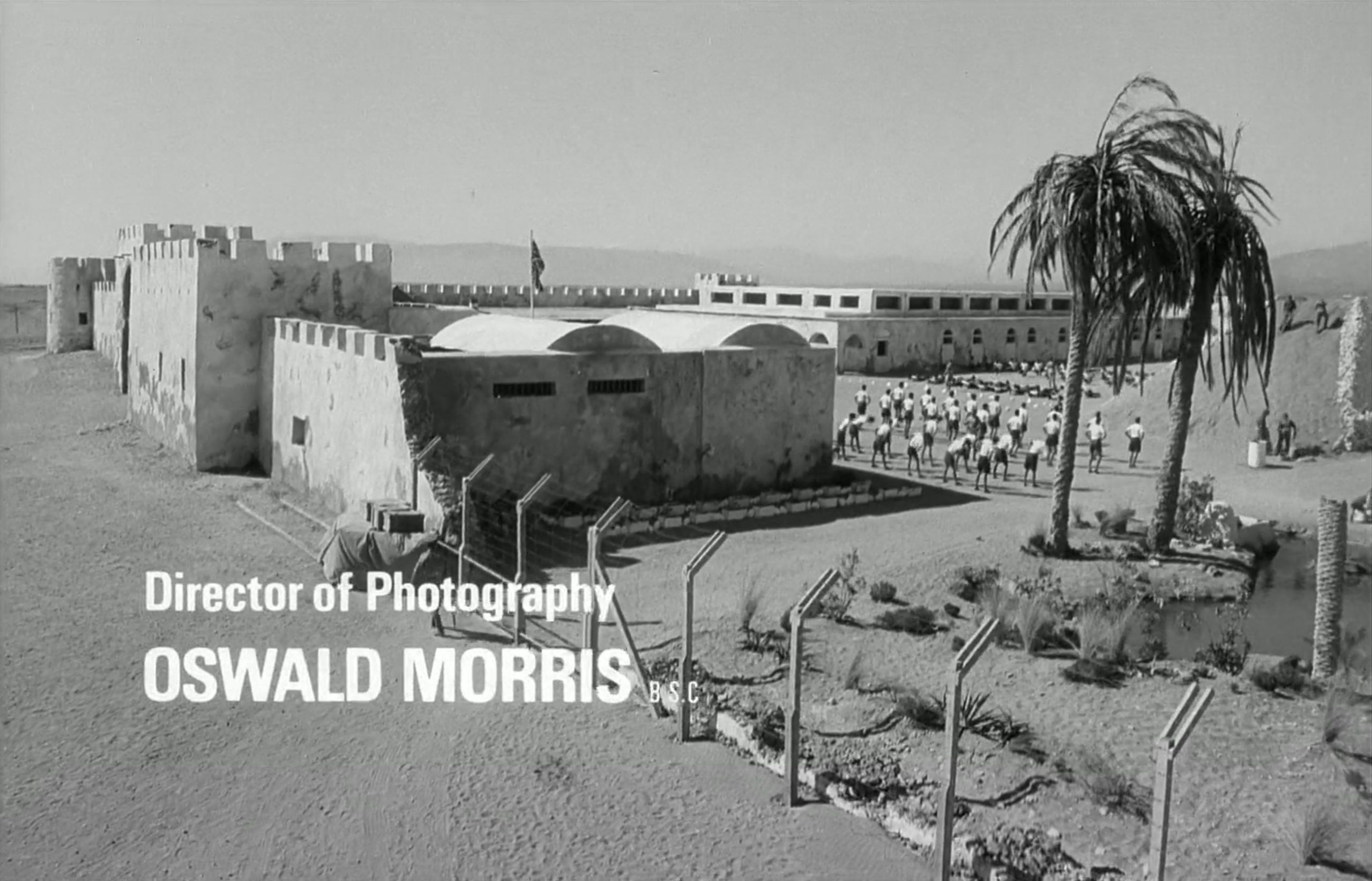

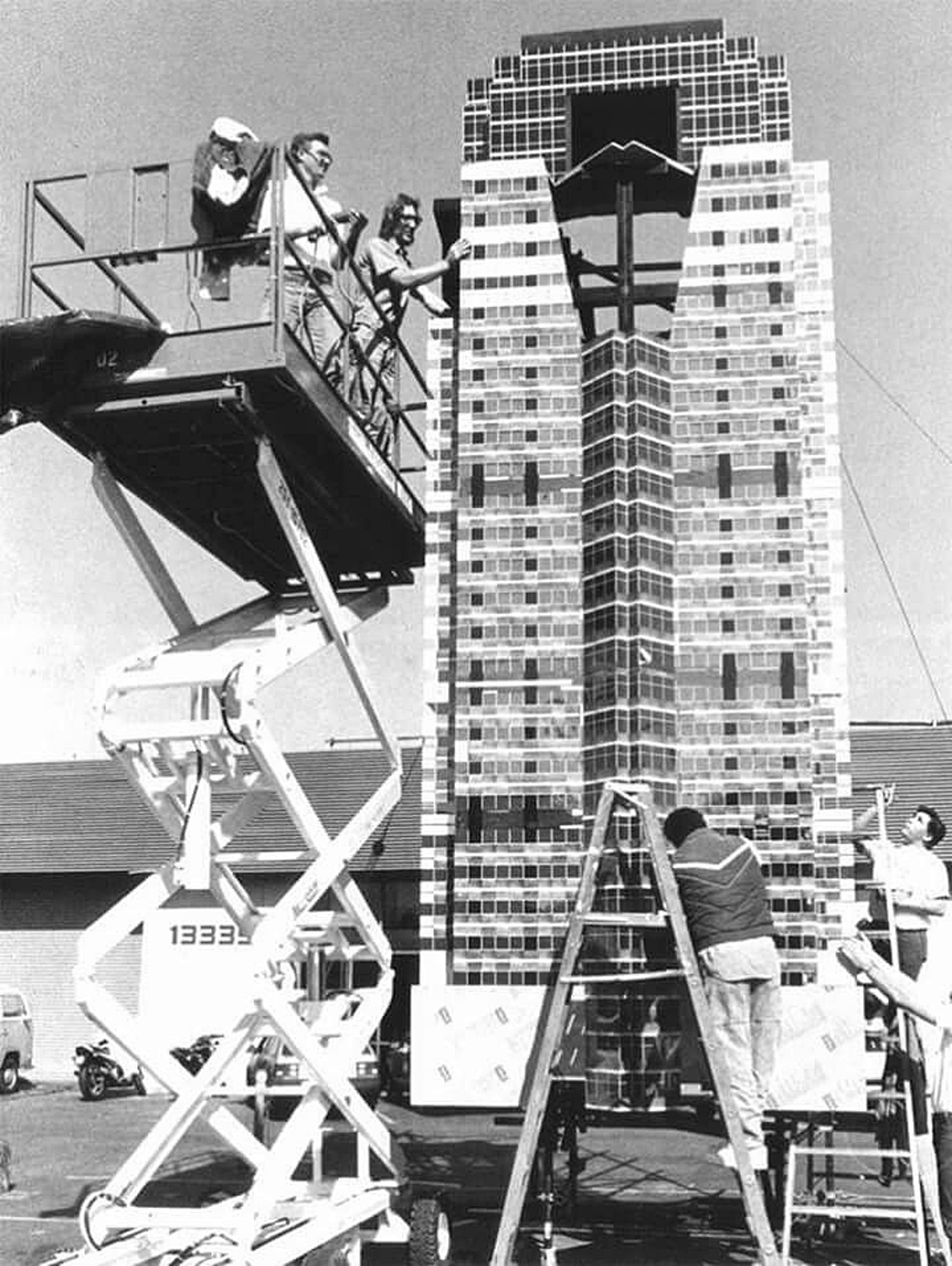

Shot in stark black and white, in a neorealist fashion, the viewer can almost feel the sweat pour off the prisoners in the harsh, blinding sun. The film opens with bravura high crane shot that sets the tone straight off, and rivals the brilliant opening tracking shot of Touch of Evil. We are voyeurs here, as at the summit of the hill, a man-made structure of sand flanked by white-washed rocks, a poor sod comes tumbling down backwards after being sweated up it. The camera then pulls back and proceeds to prowl around the camp parade ground, a bedlam of prisoners being drilled, harsh commands merging incoherently with the endless stamp of feet on sand and rock. As Roberts and co. arrive, two freed men are doubled out the gates, before collapsing on their backs outside and throwing their heads back in laughter—clearly the front line is a welcome relief after this.

Even when in the open and not in the cell block, the film feels claustrophobic and tensely nerve-shredding; many shots are close-ups, the camera angled up at guards looming forward, barking at the prisoners from beneath their slash peaks, harsh light creating unbending shadows. It takes a while to notice there is no music score, as if we’ve been parachuted into a waking nightmare. Lumet had been stationed in Oran for a while during the war, next to a G.I prison, and drew on his experience there of unusual punishment—the camp commander had a Moroccan band play all day on top of a hill in the middle of the camp. “I’m not sure how the guys in the band stood it, never mind the guys in the camp,” he told the BBC’s Omnibus. Wilson is the de facto King of the hill, brow beating the medical officer and the largely absent camp commandant. “Nobody’s gonna put a medal on us. But get this straight—one job’s as important as the next.”

The entire camp melts for 30 minutes at morning parade, the flag limp in the still air, waiting for the Commandant to return from an assignation in town with his favoured prostitute. “We’re all doing time, even the screws,” murmurs Roberts. Wilson is unduly proud of his little kingdom, and the hill, his personally created and favoured method of discipline, stating how hot it is up there. “I fancied I saw snow on top of it as I came in,” Roberts replies, doing himself no favours despite his initial intention to create no waves.

Author A. J. Black, in his book The Cinematic Connery: The Films of Sir Sean Connery, reflects rightly that:

“Lumet’s picture is the first film in Connery’s resume which truly distinguishes him from the role of Bond. Despite how intense, loud and expressly colonial it frequently becomes, Lumet’s picture is an exercise in contained tension, repression, fury and failure. Just three years after the release of The Longest Day (in which Connery cameoed) The Hill displays the kind of cynicism inherent in military conflict and the psychological trauma of conscription that later films, grappling with Vietnam and the broader cost of the Second World War and warfare generally, would have built into the DNA. It is hard to imagine the existence of films such as Platoon or Full Metal Jacket without The Hill, which serves to typify the natural rejection of authority that was becoming apparent in Connery’s own career choices and general conduct.”

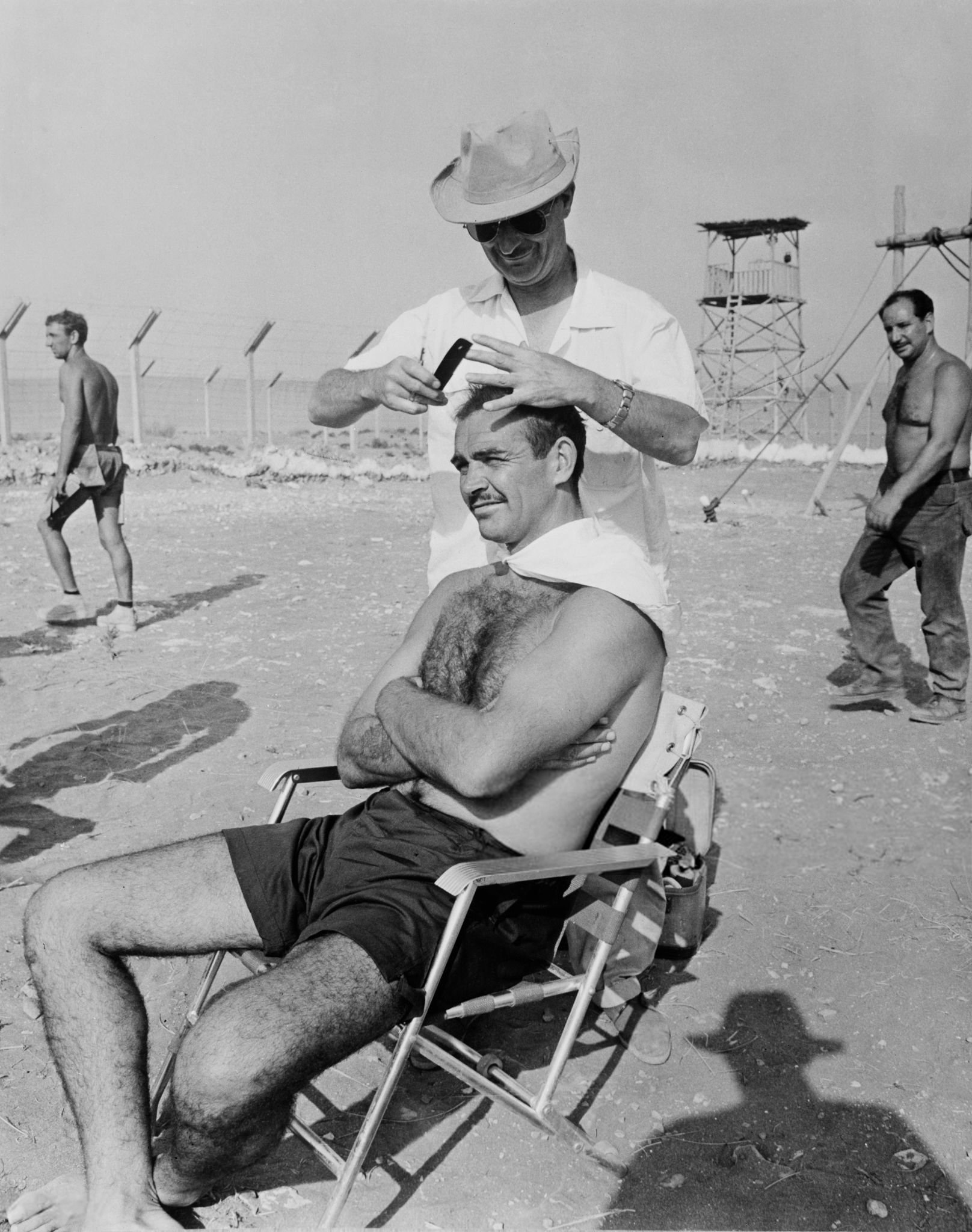

Connery told Playboy in a 1965 interview conducted over drinks in a nearby pub to his London home and later in the Bahamas during filming for Thunderball, that to him, The Hill was “the first time, truly, since the Bond films that I’ve had any time to prepare, to get all the ins and outs of what I was going to do worked out with the director and producer in advance, to find out if we were all on the same track. Then we went off like Gang Busters and shot the film under time, and it was exciting all the way down the line. Even before being shown, The Hill has succeeded for me, because I was concerned and fully involved in the making of it. The next stage is how it is exploited and received, and that I have absolutely no control over; by the time The Hill is out, I shall be involved in Thunderball. You get detached; a film is like a young bird that has flown from its nest; once out, it’s up to the bird to fly around or to fall on its arse. When Woman of Straw was shot down, I wasn’t entirely surprised. But whatever happens to The Hill, it will not detract from what I think about it.”

“As a matter of fact, it might not have been made at all except for Bond. It’s a marvellous movie with lots of good actors in it, but it’s the sort of film that might have been considered a non-commercial art-house property without my name on it. This gave the producers financial freedom, a rein to make it. Thanks to Bond, I find myself now in a bracket with just a few other actors and actresses who, if they put their names to a contract, it means the finances will come in.”

“The only thing that grows on that hill is soldiers,” sneers Williams. He’s a sadist and a coward, a bad combination, a terrifying little shit given free rein to unwittingly set the walls come tumbling down. “The court martial broke you, but I’m gonna finish the job,” he growls at Roberts. “I’m gonna bust you wide open.” Roberts is unmoved: “I’ve got your number. You’d work as a dustman if they gave you a uniform and a couple of men to yell at.”

Unable therefore to break Roberts, he sets his sights on the weakest of the new intake, Stevens (Alfred Lynch). He shouldn’t even be there; he just wants to be back home with his wife. When he’s caught out cleaning his kit with whitewash (at Roberts’ suggestion) Williams sends him over the hill in a gas mask. Lumet takes us with him, the mask over the camera lens, disorienting laboured breathing on the soundtrack. He dies of sunstroke, as diagnosed by the weak M.O (Sir Michael Redgrave), putting Roberts and Williams at each other’s throats.

Lumet cast his antagonists brilliantly, and the prisoners, who could have been bland stereotypes, are mostly played by stalwart British character actors. Roy Kinnear is super as the venal, slothful spiv Bartlett; Ossie Davis, the sole American, is the Colonial soldier who backs Roberts; and Alfred Lynch as Stevens makes you feel for the poor sod—Roberts feels guilty for laughing at him marching deliriously up and down their cell beneath the “Gestapo light,” sand happy, before collapsing. Jack Watson as McGrath is a tough equal to Roberts, but without his backbone. Both Connery and Lumet know when the “star” should stand out, and when to let the others breathe. The film overall is a great collaborative exercise, from the powerful acting, to the superb bleached-out cinematography by Oswald Morris (who worked later with Connery on the excellent The Man Who Would Be King), and editing from Thelma Connell.

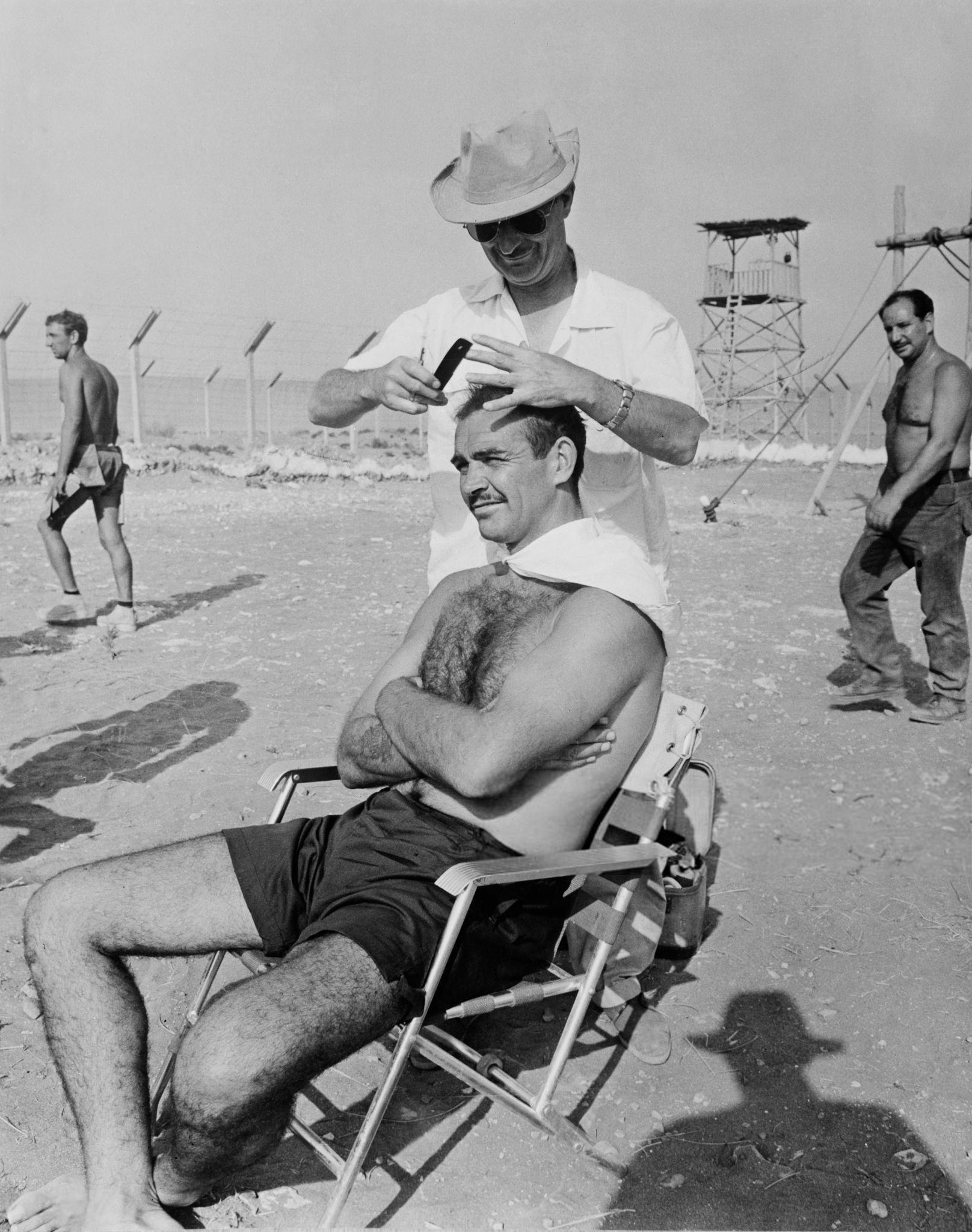

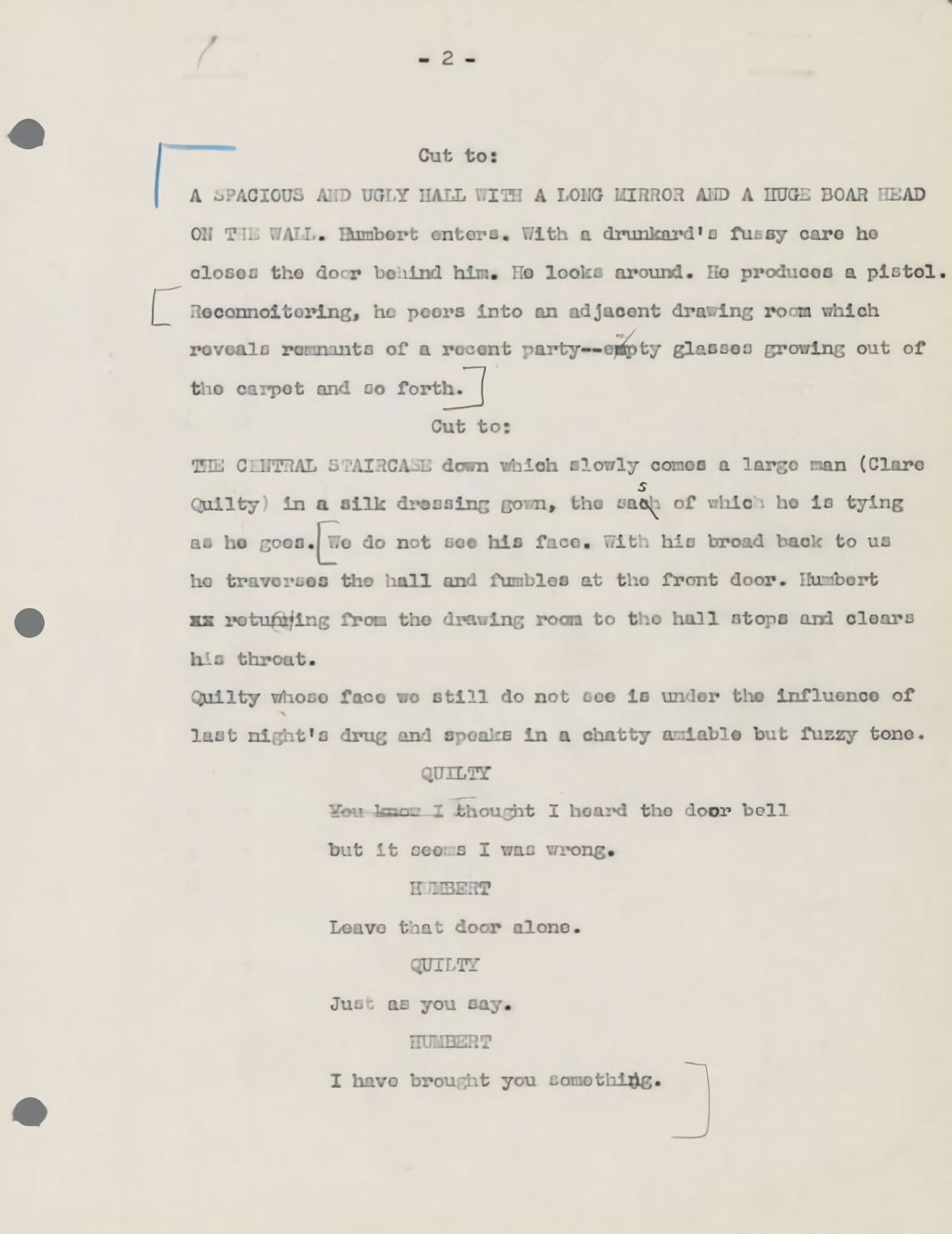

The shoot included five weeks on location in Almeria, Spain, and two weeks for interiors at the Metro Studios in Borehamwood. The outdoor set was constructed in the Dunas de las Amoladeras—near Cortijo Hoya Altica—in the Almeria region of Spain, later famously used for a number of Spaghetti westerns. At the centre of the compound stood the hill, actually constructed from 10,000 feet of imported tubular steel and more than 60 tons of stone and timber. The temperatures rarely fell below 115 degrees and despite the 2,000 gallons of pure water that were shipped in for the crew, almost everyone succumbed to dysentery during the shoot. “The physical hardship of the actual shooting is something that coincides with the physical hardship that’s necessary for the film,” Lumet told an interviewer on the set, “and through it all–the caked sands, the windstorms going on while we were shooting, the cracks in the lips–those were all for real.”

Lumet chose specific lenses so that everything in the foreground becomes more distorted, and everything in the background seems to recede further “and become less important. Even though the focus is clear, it’s much further away,” Lumet recalled. For the first third, a 24mm lens was used. For the middle third, 21mm, and for the final, 12mm—“and that was everything—close-ups, the works. To give a sense of greater and greater human distortion and background receding and receding, losing its significance in relation to what was going on up front.”

A superb set piece where Harry Andrews’ Wilson talks down a near insurrection in the cell block is a master class in long takes, editing and performance, filmed from wide angles, mostly above the hair-trigger crowd. Andrews is magnificent here, turning the prisoner’s complaints and William’s rejoinders into a cabaret act, defusing and twisting the situation. He cherry-picks a prisoner to examine Steven’s body for “any marks, bullet holes or abrasions,” knowing he’ll find none.

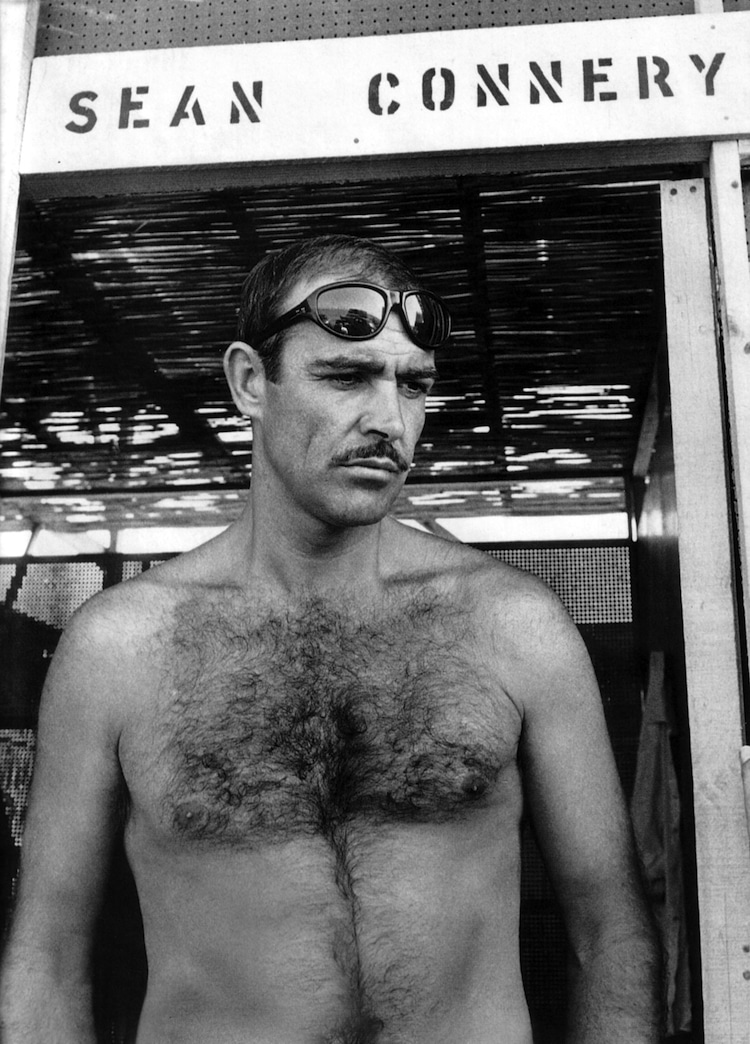

Appearing for the first time moustachioed and non-bewigged, Connery subtly weighs up the conflicts of his character—a believer in rules even though he broke them, a proud man who allows himself to be humbled, he walks a difficult line. At one point, he tells Wilson like it is: “I’m a regular soldier because I couldn’t get a bloody job in civvy street! But I was a good toy clockwork soldier—just like you are!”

Connery had served as a cadet in the Royal Navy in 1947, struggling with the strictures of rote rules and ineffectual officers. “I don’t like anyone telling me what to do. Put it another way, I don’t so much mind being told what to do provided I have respect for the person who is telling me, but there is nothing more boring, more annoying, more maddening than being told to do something by someone who is incompetent.”

He believed The Hill was one of his better roles and films, and it led to several fruitful collaborations with the sympathetic Lumet—The Anderson Tapes, The Offence, Murder on the Orient Express, and Family Business. However, The Hill’s downbeat ending and difficult, challenging subject matter and expression were commercial anathema. It must have been galling after the film was nominated for six BAFTAs and he was courted at Cannes where the film played and won for Rigby’s screenplay, to see Thunderball easily outstrip it at the box office. For Connery, a few more years of “doing time” as Bond would test his mettle.

Tim Pelan was born in 1968, the year of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (possibly his favorite film), ‘Planet of the Apes,’ ‘The Night of the Living Dead’ and ‘Barbarella.’ That also made him the perfect age for when ‘Star Wars’ came out. Some would say this explains a lot. Read more »

This original featurette shows the movie’s enthusiastic reception at Cannes and the grueling challenges of filming it in the Spanish desert.

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY OSWALD MORRIS

The following is an excerpt from Making Movies, by Sidney Lumet. Needless to say, this book is a must-read for any filmmaker.

Well, film is limited in many ways. It’s a chemical process, and one of its limitations is the amount of contrast it can take. It can adjust to a lot of light or a little bit of light. But it can’t take a lot of light and a little bit of light in the same frame. It’s a poorer version of your own eyesight. I’m sure you’ve seen a person standing against a window with a bright, sunny day outside. The person becomes silhouetted against the sky. We can’t make out his features. Those arc lamps correct the “balance” between the light on the actor’s face and the bright sky. If we didn’t use them, his face would go completely black. And an arc does cause squinting. (I’ll bet you thought all those Western heroes had that squint naturally.)

A perfect illustration of the use of contrast is: The Hill, Oswald Morris, photographer. The Hill is the story of a British Army prison in North Africa during World War II. Only the camp is for British soldiers, sent there for discipline problems or criminal behavior. It’s a brutal place, filled with sadistic punishments that are meant to break the spirit of anyone unlucky enough to be there. Wanting a very contrasty negative, we used Ilford stock, which was rarely used because photographers found it too contrasty. We decided to shoot the entire picture on three wide lenses: the first third on a 24 mm, the second on a 21 mm, the last on an 18 mm. I mean everything, close-ups included. Of course, the faces became distorted. A nose looked twice as big, the forehead sloped backward. At the end, even on a close-up with the camera no more than a foot from the actors’ faces, you could see the whole jail or enormous vistas of the desert behind them.

That’s why I used those lenses. I never wanted to lose the critical element in plot and emotion: these men were never going to be free of the jail or of themselves. That was the theme of the picture. I wanted their surroundings powerfully present at all times. To get back to contrast, the exteriors were shot in the desert. The light was blinding, the heat so horrendous that during the day we dehydrated completely. After a few days I asked Sean Connery if he was peeing at all. “Only in the morning,” he said. When we came to a close-up and the actor wasn’t facing the sun, Ossie would ask if I wanted to see the actor’s face. If I said yes, the electricians would roll up the brute. If I said no, Ossie would say, “How about eyes?” If yes, he’d tear off a white piece of cardboard—or, if the camera was close enough to the actor, take his handkerchief—and use it as a reflector, to bounce the hot light from the sky into the actor’s eyes.

In fact, in the early days of movies, before they had portable generators, cameramen used what were called reflectors—huge boards papered with silver foil, which would reflect the sun wherever the cameraman wanted. They are still used today when the budget is tight. —Sidney Lumet, Making Movies

Oswald Morris interview (2005).

403-minute interview with legendary cinematographer Oswald Morris.

EDITOR THELMA CONNELL

I have a warm spot in my heart for Margaret Booth. When I was shooting The Hill in England in 1964, she was still chief editor for MGM. By then she was in her late sixties or even older. MGM was being raided constantly by takeover groups and was, if my memory is correct, in its third change of ownership in two years. Margaret was the only person who ever knew what pictures Metro was shooting and what condition they were in. The studio sent her over to England to see the three Metro pictures being shot there. The Hill was in rough-cut form, and the other two were still shooting. She ordered whatever cut copy existed of all three pictures to be screened for her, starting at eight the following morning. Mind you, she had just arrived from California. She was an old woman, and eight in the morning was twelve midnight California time. She didn’t ask me or Thelma Connell, the editor of The Hill, to her screening but said she’d see us at one o’clock that afternoon. At one sharp, she marched into the cutting room. She said, “You’re running 2:02”—the running time of the movie. “I want the picture under two hours.” I didn’t have final cut in those days. I asked her, nicely, did she feel it was long in any particular place? “No!” she said. “It’s a fine picture and a good tight cut. But get two minutes out, or I will.”

And with that, she marched out. I was panicked. Once the studio puts its hands on a picture, there’s no way of knowing what will finally emerge. It may start with “two minutes” but wind up unrecognizable. Thelma and I sat at the Moviola (a cutting and viewing machine) and ran through the movie again. We found one thirty-five-second cut, and that was all. The next morning at ten-thirty, Margaret was back in the cutting room. I told her what we’d cut, adding that I thought any further cuts would hurt the picture. “What about…?” and she mentioned a shot. I gave her my counterargument. “What about on the shot where…,” and she mentioned another shot. Her film memory was phenomenal. She named seven or eight moments, always perfect on where the shot occurred, what took place in the shot, how its beginning or end might be trimmed—and she’d seen the picture only once. At each suggestion, I gave my reasons for keeping the shot as it was. Finally, she said, “Run it for me.” We ran the picture on the Moviola. You have to sit on a high stool because of the height of the screen, which is only eight inches wide. She sat there on the hard, high stool, watching with complete concentration. When it was over, she said, “You’re right. Keep it. It’s a good picture.” We all left the cutting room together, going in opposite directions. Thelma and I headed for the commissary. We were ecstatic, knowing the studio would now leave the picture alone. Arms around each other’s waists, we talked animatedly about what a phenomenal film person Margaret Booth was.

That night, around ten-thirty, Thelma called. In a shaky voice, she reported that Miss Booth had called and wanted to see the picture again at eight in the morning. My heart sank. Movies are full of battles you think you’ve won, only to have to fight them over and over again. She saw the picture again. Grumpily, she said, “Leave it,” and asked me to walk her to her car. We went into the hall. I asked her why she’d run the movie again. She said, “Yesterday, when you and Thelma were walking down the hall, I thought you were laughing at me.” I stopped. I couldn’t believe what I’d just heard. I said, “Margaret, I’ll argue with you. But there’s no way I’d try to con you.” She started to cry. “I know,” she said. “You’re not one of them. I’m so tired. All those people”—she may have said “bastards”—’fighting over the bones of this studio. None of them know anything or care about pictures. And I’m the only one who knows what’s being shot and what will be ready for release at Easter or Christmas. And everybody lies to me while dumping more and more decisions on me. And I have no help. And I’ve got to go on to India now. We’ve got a picture there and it’s in trouble and I’m the one who may have to pull the plug on them. Last night I felt so tired. And I thought you and Thelma were conning me also.” I opened her car door. I kissed her cheek. She told the driver, “Heathrow Airport.” It’s the last time I saw her.

Like everything else in movies, editing is a technical job with important artistic ramifications. While it’s absurd to believe that pictures are “made” in the cutting room, they sure as hell can be ruined there. So many misconceptions exist about editing, particularly among critics. I’ve read that a certain picture was “beautifully edited.” There’s no way they could know how well or poorly it was edited. It might look badly edited, but because of how poorly it was shot, it may in fact be a miracle of editing that the story even makes sense. Conversely, the movie may look well edited, but who knows what was left on the cutting room floor. In my view, only three people know how good or bad the editing was: the editor, the director, and the cameraman. They’re the only ones who know everything that was shot in the first place. —Sidney Lumet, Making Movies

VISUAL HISTORY WITH SIDNEY LUMET

Sidney Lumet discusses his directing style developed over 50 years of filmmaking including such noteworthy films as 12 Angry Men (1957), Long Day’s Journey Into Night (1962), Dog Day Afternoon (1975) and Network (1976). Interviewed by Marc Levin.

In his three-hour Archive interview, Sidney Lumet (1924-2011) speaks of his work as an actor on the stage before he became a director in television. He recalls his work on the television series Danger (1950-55) and You Are There (1953-57), both “live” dramatic shows of the time. He discusses the use of blacklisted writers on these shows and how the material they wrote often reflected the era of McCarthyism. He also discusses other television dramatic anthology series he directed, including Omnibus, Goodyear Playhouse, The Alcoa Hour, Studio One and Kraft Television Theatre. He describes his direction of the well-known television special The Sacco-Vanzetti Story and The Play of the Week: The Iceman Cometh, both of which aired in 1960. He speaks of his transition to a feature film director with 12 Angry Men in 1957 and his work on such other feature films as the Paddy Chayefsky’s satire, Network (1976). Dr. Ralph Engleman conducted the interview on October 28, 1999 in New York, NY.

This is a compilation of interviews conducted with Sidney Lumet throughout his carrer, where he talks about the art of directing, his beginnings and films.

The Hill © Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Seven Art Productions. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or donate directly below: