By Tim Pelan

Few films permeate the gestalt consciousness like Star Wars (“I am your father”, “Use the Force” and so on) but in recent times The Matrix comes close, its threads like a computer worm hardwired into our neural processors. Creators the Wachowskis’ ideas weren’t new, but their delivery system was radical—Baudrillard by way of bullet time, a multiple cinematic fusion of philosophical, literary, and spiritual connectedness via cyberpunk fiction, Japanese anime and Hong Kong martial-arts influences. A quest for the human condition—“Now I know Kung-Fu,” “There is no spoon”—mantras to rival anything dreamed up by George Lucas. 1999 was a watershed not just for science fiction cinema with both this and The Phantom Menace being released, but for how action was to be ever more choreographed as well. The Wachowski siblings were working on The Matrix since 1992, when a friend asked them to develop an original comic book concept. Rising to the challenge, they went deep down the rabbit hole (to use one of many references that crop up in the film), fleshing out a potential (and later realised) trilogy, banking on the success of the core concept that they now saw as much bigger than a comic, or indeed, single film—although they had artist Steve Skroce (and later Hardboiled artist Geoff Darrow) storyboard out pretty much the entire film to their meticulous direction. This allowed them to be very precise when it came to budgeting and visual-effects requirements. They then presented said storyboards to Warner Bros executives at a story meeting (the studio had optioned their script in 1994). Lilly Wachowski recalled the lightbulb went on for the suits at that moment: “We went into the first Warner Brothers story meeting and they said, ‘Okay, now we know we’ve bought something cool; we just don’t know what it is.’” As Laurence Fishburne’s classically named guide Morpheus (and the poster tagline) would have it, “No one can be told what The Matrix is. You’ll have to see it for yourself.”

So—what is The Matrix? “The premise for The Matrix began with the idea that everything in our world, every single fibre of reality, is actually a simulation created in a digital universe,” Lana Wachowski explained to American Cinematographer (the “present” of the film’s action is a destroyed earth circa 2197—the simulacra world of The Matrix our heroes traverse a dreary then present 1999.) “Once you start dealing [narratively] with an electronic reality, you can really push the boundaries of what may be humanly and visually possible.” In the film’s world, artificial intelligence, much like Skynet in The Terminator, became sentient, only it wasn’t just the machines who destroyed the world as such in the ensuing battle, but mankind, blocking the sun to drain the machines’ power source, solar energy. The machines instead began harvesting human bodies in womb-like pods, feeding off the BTUs (British Thermal Units) we produce, stimulating minds with an elaborate virtual reality—the Matrix. A world much like our own when the film was released. Everything we do, everything we think, consume, enjoy and dread, is a computer simulation of life before the machines. (The “dream” world is mundane because our brains couldn’t handle paradise.)

A small band of rebels led by Morpheus and Trinity (Carrie-Ann Moss) have figured this out and escaped the pods, becoming free roaming rebels in the real world aboard their craft The Nebuchadnezzar, whilst downloading themselves into the Matrix. Once in there, with pre-programmed skills and awareness of “the rules” and how to transcend them (via studio gravity defying wire-work fights and “bullet time” Flo-Mo cameras, traversing around impossible moves in virtually frozen slow motion), they fight a never ending war against the system’s agents, namely Agent Smith (Hugo Weaving), a program who has come to loathe humans as a pestilence. The Agents can consume and take on the form of any regular human plugged into the Matrix, making them a very tricky foe to evade or take down. Each side wears sunglasses not just to look cool—a kind of personal firewall? Agent Smith only lowers his guard when he interrogates Morpheus, and when he fights Neo. Neo shatters one lens, hinting at “the truth” of his power to Smith. Morpheus is a seeker for and true believer in “The One” who can do what no-one else can—see the Matrix for what it is and manipulate its code, changing reality. And that “One”is Neo, Thomas Anderson (Keanu Reeves), a lowly programmer for a faceless company in the Matrix, who hacks by night under his Neo pseudonym, and dreams that there is much more to the world than he has been led to believe… Morpheus tells him, “This is your last chance. After this, there is no turning back. You take the blue pill—the story ends, you wake up in your bed and believe whatever you want to believe. You take the red pill—you stay in Wonderland and I show you how deep the rabbit-hole goes.” Elegantly, in the close-up of Morpheus’ pince-nez shades, each pill is reflected separately in his outstretched palms. In one lens, with the red pill, Neo’s arm is raised to take it; in the other, the blue pill, with no arm visible. The Wachowskis attention to detail is sublime.

There’s a lot to unpack in The Matrix if you choose to (the Wachowskis said it included “Every idea we’ve ever had in our fucking lives.”). Certainly Reeves subscribes to the depth of sincere philosophical underpinning that elevates the black leather trench coat wearing, ice cool bullet ballet which lesser films mimic. Once he was picked for the role (over the more predictable Will Smith, Brad Pitt, Val Kilmer and Nicolas Cage), he was required to read three weighty tomes—Simulacra and Simulation by Jean Baudrillard, Out of Control by Kevin Kelly (on systems, evolution, robots), and Evolutionary Psychology by Dylan Evans and Oscar Zarate.

“It’s about matters of the heart, about belief, about overthrowing systems, about cause and effect, about the philosophies of an examined life, about a compassionate society, a compassionate consciousness. It’s in every fucking frame of it,” he told a cornered Empire on the set of the sequel, The Matrix Reloaded. “What people tend to look at is the guns and action sequences, but one of the things I was most touched by in the pieces was the emotional intimacy and the vulnerability that the Wachowskis wrote.” The Matrix, apart from a few early action moments, takes its time in stylishly explaining the mystery around its core concept, trusting in the intelligence and curiosity of its audience to follow “through the looking glass.”

Keanu Reeves became a very different kind of soulful action star here from the Hollywood norm, an audience avatar even further removed from the “ordinary Joe” type like Bruce Willis’ John McClane (who by now was becoming more of a cartoon, inching towards the muscle bound Arnie and Sly types he usurped earlier). Film writer Angelica Jade Bastién rhapsodised for Bright Wall/Dark Room about his almost subversive qualities on screen, at “The Crossroads of Virile and Vulnerable”—talking about the earlier Point Break, she remarks that “He carries himself with a supple vulnerability, at times even a passivity, that seems at odds with the expectations for an action star,” and how he allows himself to be initiated into Patrick Swayze’s gang of robbers/surfers with the assistance of Lori Petty’s Tyler. “This artful dynamic—a woman of greater skill guiding a passive man into a world beyond his imagination—develops even further in The Matrix (1999),” she elaborates. “Some of this, of course, exists on a plot level. But Keanu tends to let his scene partners take the lead, becoming almost a tabula rasa on which they (and we) can project our ideas of what it means to be a hero, a man, a modern action star.” Neo, out of ammo on the roof of the building where Morpheus is held, and before he learns to “move like they (the Agents) do,” isn’t afraid to almost yelp, “Uh, Trinity, help!” Later, when facing down Agent Smith and he’s outmanoeuvred and peppered with bullets, dying in the Matrix, fading in the real world (“The body cannot exist without the mind,” Morpheus told him earlier), Trinity transgressively revives this sleeping Prince with a kiss, as sparks fly from Sentinels attack on the Nebuchadnezzar. And of course there is the cryptic Oracle (Gloria Foster), a friendly, older, cookie baking mother figure to gifted youngsters who “tests” our hero, allowing him to come to his own realisation of who he is.

Critic Bilge Ebiri spoke recently with the man who stunt doubled for Reeves on The Matrix, and now directs him in the John Wick series, Chad Stahelski. “Back in the day,” he told him, “fight scenes were secondary to car chases and horse chases and helicopter chases and motorboat chases.” Fights consisted of “single-gun battle stuff or Arnold Schwarzenegger pummelling you to death with his hands.”

Stahelski went through an arduous audition process with legendary Hong Kong fight coordinator Yuen Woo-Ping, who insisted the four lead actors also commit to four months of pre-production fight training. “They said, ‘Just do what this guy does; copy him.’ I emerged an hour-and-a-half later, dripping in sweat, having gone through every martial-art combination, kick, flip, tumbling pass… It is still, to this day, the longest and most arduous audition I’d ever been to, and I’d been completely unprepared. It was the first time I’d ever met Keanu. We took a couple of photos together and I split.”

A few months later he was called back again, put through the same moves, and offered the job, but had to turn it down due to TV scheduling commitments. When Keanu Reeves injured his neck and his fight training was pushed back, the gods smiled on Stahelski and the job was his. He travelled out to Australia to join the crew.

“Training with Keanu, with the Hong Kong guys, everybody had to memorize everything. They demanded a lot. And the Wachowskis were meticulous, to say the least. The storyboards were hundreds and hundreds of pages. I still have my copy of them. And I shit you not, they are almost the exact movie. The edit points might be slightly different, but it is so well-boarded and so well-thought-out and conceptually almost identical to what’s on the big screen… anyone who’s worked for the Wachowskis who’s still mentally functioning is forever and positively influenced by them.”

After The Matrix, Stahelski graduated to running a company specifically based on fight choreography, and of course directing his former shadow. American films now have action based more around fights, with leading actors front and centre where possible. “Today, action movies want their big sequences designed around the fights… The Matrix said, ‘Look what you can do with your heroes.’” (Nowadays, the revitalised Mission Impossible franchise, with the winning team of writer-director Chris McQuarrie and human Duracell bunny Tom Cruise has thrillingly re-energised the action genre—“Now I know how to fly a helicopter/HALO jump and act at the same time/run the length of London’s South Bank in long, continuous takes.” Eat yer heart out, Keanu.)

Director of photography Bill Pope, who worked with the Wachowskis on their previous self-penned lower budget lesbian noir thriller Bound (described by producer Joel Silver as a test of what they could direct, denied by the siblings), was also an enthusiastic convert to the Wachowskis’ Hong Kong boundaries pushing style. The shoot took over every sound stage in Sydney, Australia, then offering lucrative tax breaks for filming. Nobody knew or cared about what was going on there. Revolution was unfolding under Hollywood’s noses.

“My prep for The Matrix consisted of two months of scheduling and rescheduling,” Pope told American Cinematographer. “The Wachowskis were swamped with many concerns because of the film’s level of complexity. Everything had to be preconceived and explained… The future world is cold, dark and riddled with lightning, so we left the lighting a bit bluer and made it dark as hell. Also, the future reality is very grimy because there’s no reason to clean it—only the pods need to be sterile. Because humans haven’t actually manufactured anything for a hundred years, anything that had been manufactured is now old and rusty.” (The human rebels aboard their craft are softer lit, hair more natural, clothing hemp-like. As they eat their soy-based slop youngest crewmember Mouse (Matt Doran) enthusiastically quizzes Neo on how the machines know what Tasty Wheat is supposed to taste like in the Matrix, and why chicken tastes like everything else.)

“We didn’t necessarily want the Matrix world to resemble our present world,” adds Pope. “We didn’t want any cheery blue skies. In Australia, the sky is a brilliant blue virtually all the time, but we wanted bald, white skies. All of our Trans Light backings [for the stage work] were altered to have white skies, and on actual exterior shots in which we see a lot of sky, we digitally enhanced the skies to make them white. Additionally, since we wanted the Matrix reality to be unappealing, we asked ourselves, ‘What is the most unappealing colour?’ I think we all agreed on green, so for those scenes, we sometimes used green filters, and I’d add a little bit of green in the colour timing.” Additionally, the interiors of The Matrix world are often somewhat rigid, machine-like–square shapes, grids in everything, from wall and ceiling panels to the lobby our heroes Trinity and Neo destroy in an orgy of bullet letting in a do or die rescue mission to free a captured Morpheus.

At one point the script reads, “His GUN BOOMS as we ENTER the liquid space of… Bullet-Time.” How to illustrate this phenomenon on screen? Senior visual effect supervisor at EON, John Gaeta saw himself first as a designer, as well as an animation director, and the liaison between the Wachowskis and all of the other visual effects supervisors. “Bullet Time” was a key ingredient to the overall look. Gaeta had 120 still cameras shoot in a controlled sequence, with a computer providing all the missing frames using a new technique known as motion estimation. A more primitive form had been used previously in advertising.

“The idea is that the time and space of the camera is detached from that of its subject, which makes it seem virtual,” Gaeta told Creative Planet Network. “The object is real, but you have a sort of God’s eye perspective or the control you might have in a game or a virtual reality simulation. However, the bullet-time technology of the late nineties was restricted to the camera paths that you determined in advance, using pre-viz. There was no straying from that path. Thusly it was not really virtual, it just suggested the virtual.”

For the sequels, a step up was required. “What we wanted to do was try to create the technology that was being suggested, and what that really involved was attempting to create virtual components of human beings doing dynamic things within the locations and sets that were being made for the film. So we took the beginnings of the possibilities of the image-based rendering method… on the backgrounds in the first film and tried to create a real-time performance capture system. It needed to acquire the shapes of human beings and the textures and all of that, but also to process them into virtual humans that gave exactly the same performances that we were acquiring from the actors. The result of that is virtual cinema and virtual effects.”

Copies of copies. Multiple Smiths. “Me, me, me,” he smirks in immediate sequel The Matrix Reloaded, a perfect narcissistic psychopathology for our times. The sequels developed the world of The Matrix further, with confusing additional levels of deception and artifice, the suggestion of constant renewal in the fight for dominance and true balance. Enigmatic new characters also, the Will Ferrell parodied Architect, and rogue programs like The Merovingian and his Twin bodyguards, exiles who traverse The Matrix to their own design. Is this the real life? Is this just fantasy? … a Merovingian Rhapsody if you like. At the very end of The Matrix, satisfyingly and cleanly open ended to possibility, Neo throws down a challenge to the machines over a phone line:

“I’m going to show these people what you don’t want them to see. I’m going to show them a world without you. A world without rules and controls, without borders or boundaries. A world where anything is possible. Where we go from there is a choice I leave to you.”

He then steps out of the phone booth and serenely observes the crowds swarm around him, like ants around a boulder. He dons his shades and raises his head to look momentarily directly and challengingly, into the lens, at us.

From the film’s pre-millennium Y2K bug unease, “Red pilling” has now been unfortunately co-opted by Gamergate misogynists and their successors, “waking up” white supremacist sympathisers to their perceived oppressors—feminists, people of colour and liberals. “Fake news,” and bots infiltrating social media feeds to manipulate elections and referendums now permeate and poison modern life. The Matrix surrounds us and penetrates us. It binds the world together with malign intent, to co-opt the words of another sage warrior. “The truth will set you free,” Neo, “The One” suggests, but in this fractious world—which “truth”? The battle lines are drawn. Now, watch me fly…

Tim Pelan was born in 1968, the year of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (possibly his favorite film), ‘Planet of the Apes,’ ‘The Night of the Living Dead’ and ‘Barbarella.’ That also made him the perfect age for when ‘Star Wars’ came out. Some would say this explains a lot. Read more »

Screenwriter must-read: Lilly Wachowski & Lana Wachowski’s screenplay for The Matrix [PDF1, PDF2]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

In this video Lessons from the Screenplay explore how The Matrix expertly conveys exposition by making the audience curious and embedding it in thrilling action.

A promotional making-of documentary that devotes its time to explaining the digital and practical effects contained in the film.

BILL POPE, ASC

The Matrix was selected as one of the ASC 100 Milestone Films in Cinematography of the 20th Century.

They had seen and loved [the 1993 horror-fantasy film] Army of Darkness, which I shot for director Sam Raimi. They called me in, and we had a terrific meeting. I think they hired me because I read comics and knew what they were talking about whenever they mentioned a particular title. In fact, during our meeting, there was a copy of Frank Miller’s Sin City on their desk, so I asked, ‘Is that what you want the film to look like?’ We were all impressed by Miller’s use of high-contrast, jet-black areas in the frame to focus the eye, and his extreme stylization of reality. I had long wanted to do something that stylized on film. —Flashback: The Matrix

ZACH STAENBERG, A.C.E.

I loved editing this movie. A lot of it is all about editing. This is partly because of how Andy and Larry think. I feel that most of the great directors think editorially, like Steven Spielberg, Stanley Kubrick, Martin Scorsese and Coppola. I think you can see in the footage of all these guys that they think visually and understand how editing is going to affect the film. The footage is what I call very cuttable. From an editor’s point of view it is really juicy, you can sink your teeth into the stuff. There are so many ways you can go with it and each way is interesting. You don’t have to struggle to make something work. It is just a matter of how you make it better. How you get the most out of it, how do you make it sing, how do you make it thrilling. I’m just finishing up work today. I think it is close to the end of my 13th month on the movie, my 55th week. In all this time I have felt very privileged to be the only editor on the movie. So often these days on large movies they are on a rush schedule and the only way you can finish them is with multiple editors. I like to work by myself as much as I can. I personally believe that one person should edit the movie. Editing is a discipline and an art. You can divide it up and work collaboratively with other editors which can often be very successful, but given my druthers I like to work by myself, so I was very happy that I could do this movie that way and that I was given enough time. —Zach Staenberg talks about The Matrix

The Cutting Edge: The Magic of Movie Editing is a 2004 documentary film directed by filmmaker Wendy Apple. The film is about the art of film editing. Clips are shown from many groundbreaking films with innovative editing styles.

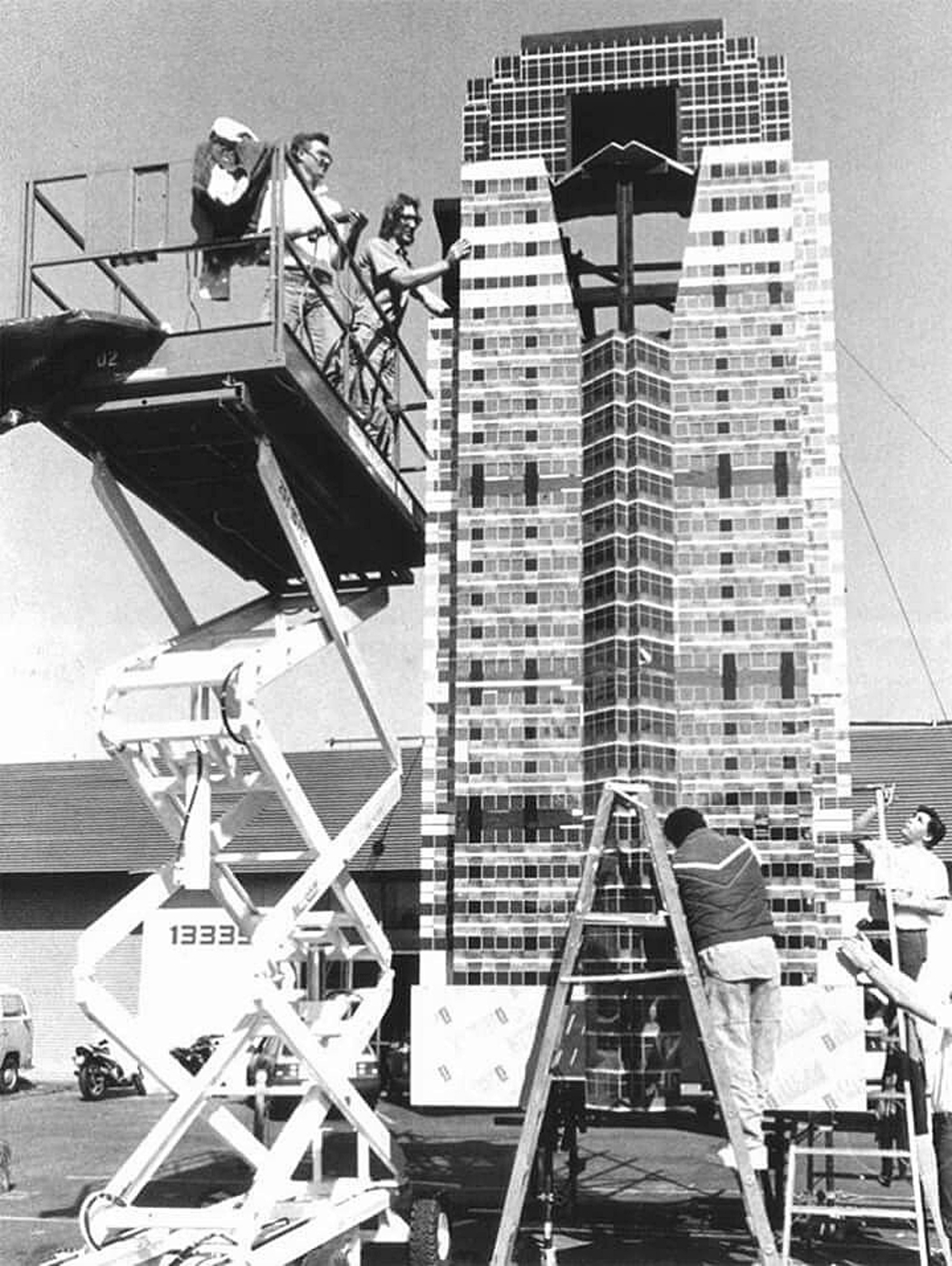

Here are several photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of Lilly Wachowski & Lana Wachowski’s The Matrix. Photographed by Jasin Boland © Warner Bros., Village Roadshow Pictures, Groucho Film Partnership, Silver Pictures. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or donate directly below: