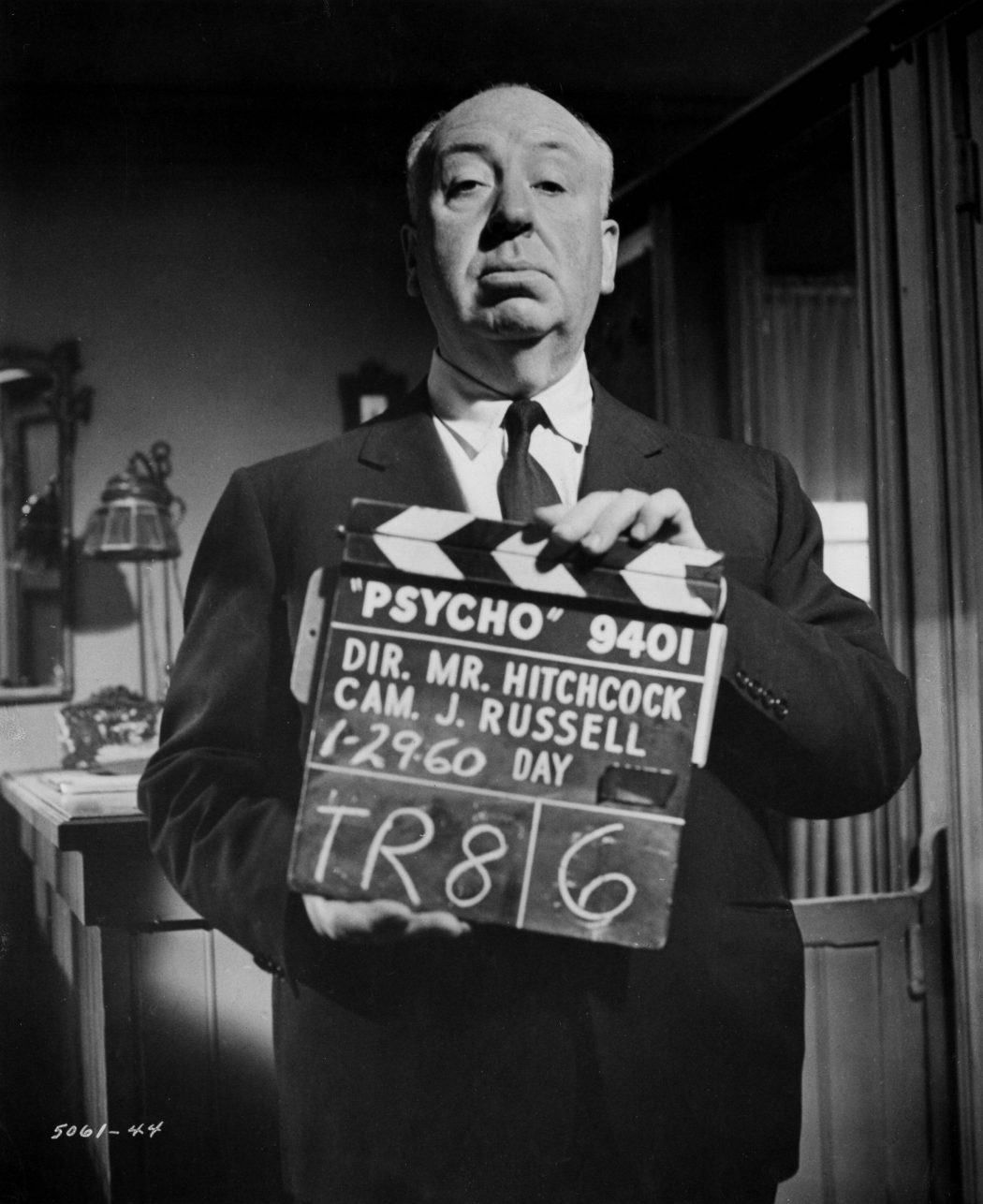

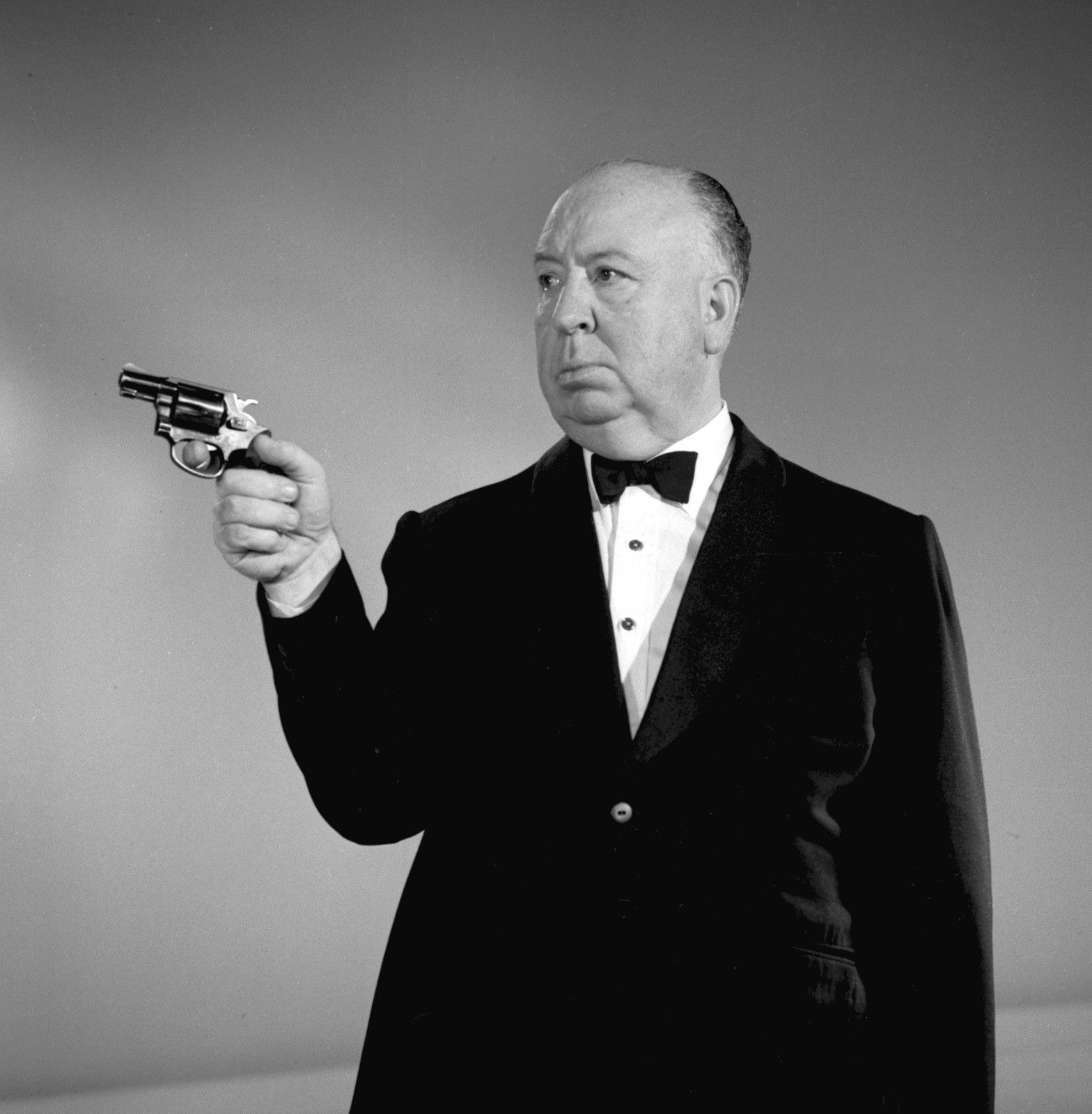

Desert Island Discs is a biographical and factual radio programme, broadcast on BBC Radio 4. It was first broadcast on 29 January 1942 and celebrated its 70th anniversary in early 2012. Each week a distinguished guest (“castaway”) is asked to choose eight pieces of music, a book and a luxury item that they would take if they were to be cast away on a desert island, whilst discussing their lives and the reasons for their choices. It was devised and originally presented by Roy Plomley. Alfred Hitchcock was the guest in October 1959. The following is the only surviving extract in the BBC Archive.

Transcription courtesy of The Hitchcock Zone.

I’m a very good listener. From an early age I was a devotee of symphonic music—the Albert Hall on Sunday, the Queens Hall, and so forth. You know, I’m a Londoner and I was quite a devotee of the theatre from a very early age, a “first nighter” I think, probably, at the age of 16 or 17, maybe earlier.

Were films an ambition from your school days or, like most of us, did you just happen to get into the job you like?

I would say that, apart from being a devotee of the theatre and the concert, of course, films also had an important part in ones amusements. But my interest became a little more deep—beyond shall we say the “fan magazine” stage—I think my reading at that time, where films were concerned, was the trade magazine. So I really got deeply interested in pictures.Were films your first job?

No, no—my first job was a technical engineering job, actually. I had studied engineering and I was in the estimating department of a cable company and eventually then I gravitated to the advertising department where, having taken a course of art at the University of London, I was able express myself there. Through that, I went into the designing of what were, in those days of silent films, the art title. They were rather naïve affairs, when I look back on them. The title would say “John was leading a very fast life” and I would draw a candle with a flame at both ends underneath. From there, into script writing—writing scripts—and then art direction and eventually into direction.What was the first picture you directed?

The very first picture I directed was called The Pleasure Garden—it was a melodrama—and it was made in Munich, Germany, and I had to direct it in German.Was that difficult? Was your German pretty good?

I’d say it was enough to order a good meal, you know! But it was silent pictures, so that one wasn’t involved in the finer points of dialogue.Well then a few years latter you directed the very first British sound film…

That’s right—that was called Blackmail, yes.You were to make quite a number of varied films before you settled down to specialise in suspense pictures. Which film was the turning point? Which one made you say “this is what I can and is what I want to do”?

Well, I really think the film The Lady Vanishes pretty well set the pattern. I would say this—I think it’s more since one’s been in American that one’s been, what is called, “typed.” There, much more than in England, standardisation, as you well realise, is a very important part of the national life.When you when went to work in Hollywood, did you find any major adjustment necessary? Your films had always been very British in background and character.

No, not at all, because, you see, the first film I ever made in America was an English film,—it was called Rebecca. And I have made many English films since… the second film I made as called Foreign Correspondent and that was all made in London and Holland. No, the thing that I began to learn was the fact that an audience is the same world over and not to make films for one audience, but to make them for a world audience.You work as a freelance, don’t you so that you have complete freedom from interference, to work just the way you want to from the first idea right up to the final film.

Yes.Which has been your favourite film, which has given you the most satisfaction?

Well, I actually make many types of films—in other words, the adventure story or the psychological thriller. I think my favourite is called Shadow of a Doubt, because this film combined many elements—the element of suspense, the element of the local atmosphere of a small town, and quite an amount of character… and also the enjoyment of having worked with Thornton Wilder.I remember it well. The pattern of the film industry is changing very fast—audiences, they say, are losing the cinema habit and there are fewer films. What do you think will be the future pattern?

I think that audiences now have become selective and the assembly line has gone. I think each film stands on its own merits. I think one has to tackle it in terms of making a film that will attract audiences for its special virtues, not just “another movie.” As you say, the habit has gone. The nearest I could compare it would be the publishing of a new book or a play. Now, if it’s successful, it has a good run. If it isn’t successful, then it’s gone.Yes, to cut out this present, rather ridiculous release system where every film, whether it’s a masterpiece or a piece of tripe, always plays one week.

Well, that’s ridiculous. As you know, why shouldn’t a film have its run, if there are people who are willing to pay to see it, other a period of weeks, just as the States play?Yes, you’ve moved into the television field as well, haven’t you?

A little sideline, yes. Of course, that doesn’t compare at all with the making of pictures, anyway.You’ve told us about the last film you’ve been making. Are you planning another one?

I’m planning a psychological film, it’s called Psycho and it’s in the nature of, shall we say, a rather gentle horror picture.Splendid! And, as usual, are you going to be in it yourself, for just a brief appearance?

Oh, I always make the brief appearance but now, of course, especially in America, ones visage is so familiar now that I have to get into the picture and out as quickly as possible, so as not to spoil the story.You have the reputation in the studios for being a practical joker. Would you say that’s justified?

Not today. As a matter of fact, the practical jokes that I used to enjoy were always benevolent ones—they were never burning the seat of another person’s pants. Not that kind of thing! As a matter of fact, I gave it up because they were rather too generous—they were expensive and costly, so I don’t do it anymore.

Listen now or download to keep:

- Alfred Hitchcock

- Mel Brooks

- Deborah Kerr

- Arthur C. Clarke

- Alan Bates

- James Stewart

- John Huston

- Judi Dench

- Marlene Dietrich

- Ian Fleming

- Dirk Bogarde

- Jack Lemmon

- Bob Hoskins

- Ken Russell

- Alan Parker

- Anthony Hopkins

- James Ivory

- Helen Mirren

- James Mason

- Frank Oz

- Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger

- Otto Preminger

- Mike Leigh

- Michael Caine

- Stephen Frears

- John Malkovich

- Terry Gilliam

- Elia Kazan

This is quite priceless. 1966 interview with Alfred Hitchcock on filmmaking, simplification of identification, visual clarity, actors and improvisation, humour of the macabre, being a traditionalist, making television, suspense and more.

Documentary about Hitchcock’s influence on other directors and films.

Transcript courtesy of The Hitchcock Zone.

Once you’ve sort of mined the classics and they become like logos that you see everywhere, the beauty of Hitchcock’s work is that the more subtle moments are even more powerful and more lasting, I think, ultimately, in the less bravura scenes in pictures like Psycho. In Psycho we have two or three very strong bravura moments which, of course, are the shower scene, the killing of Martin Balsam, the shocking ending… But the sequences that continually give me inspiration are the sequences in which she’s driving. The camera is very, very dead center on her, it’s very precise. And when you see her point of view, it’s dead center. It isn’t slightly off, that’s a big difference. These are very specific shots and they exist in almost an abstract way. You know, here it’s stripped down black and white. It’s like a dream, and yet you’re still awake. And you know with that music, too, that something terrible is going to happen to her. But it can’t because she’s the lead of the film. Come on, she stole 40,000 dollars, she’s on the lam, she’s running away, that’s the plot of the picture, let’s see what happens. So I was one of the ones who bought that completely. We were up there that night at the Mayfair Theater, it was called. And that was one of the first films I ever saw that said, Please do not reveal the ending. We were yelling at people as they were coming out of the theater, saying, What happens, what happens? Don’t ask, don’t ask, we’re not saying. We were all laughing and running. It was like a circus… a circus. —Martin Scorsese

Attention, dear readers: If you find this place worth visiting, and would be glad to continue to have your breath taken away by these pearls of the world’s cinematic history, consider supporting us and helping this site stay afloat. Cinephilia & Beyond has never been about profit: it’s a labor of love that gets us through the day. Small gifts from the heart, however, as signs of your much needed support and always welcome appreciation, will help us build an online archive that film buffs like you truly deserve. Our current goals: We DESPERATELY need a new scanning/preservation equipment—this will enable us to publish rare and usually comercially unavailable material that filmlovers will get a chance to read and advance through them on their way of becoming better filmmakers. Please make a donation today