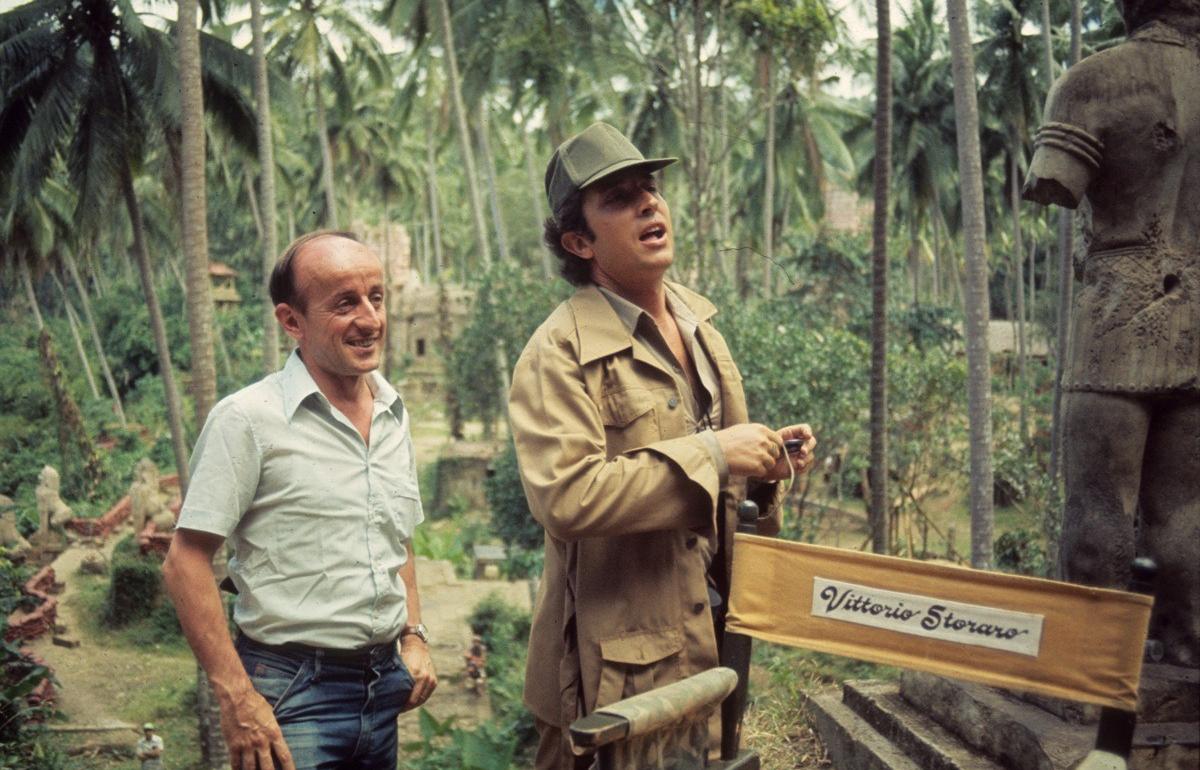

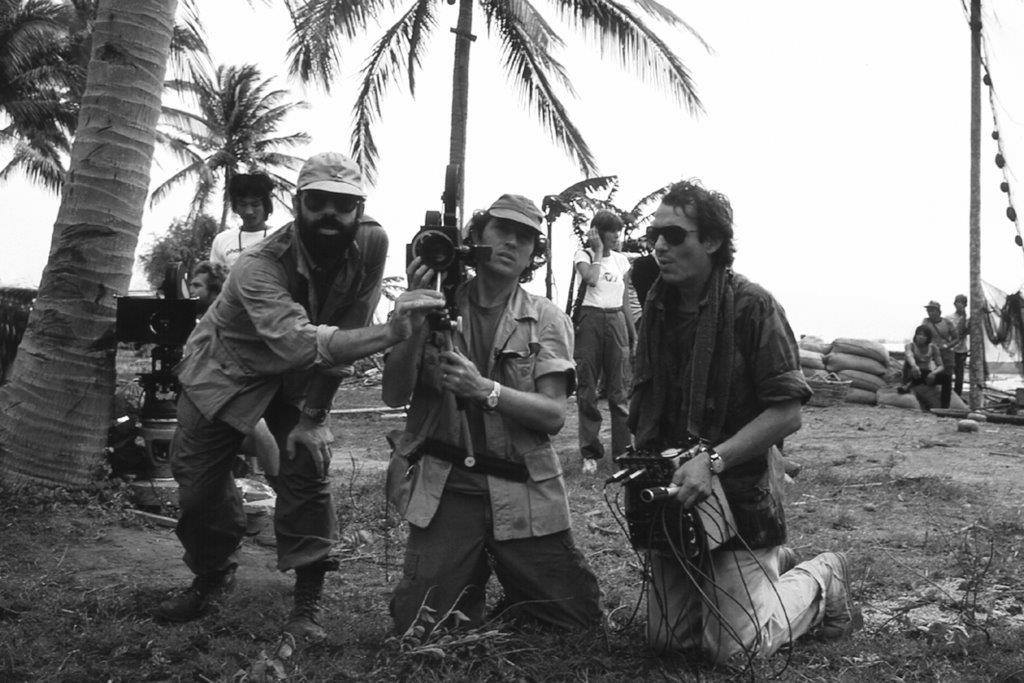

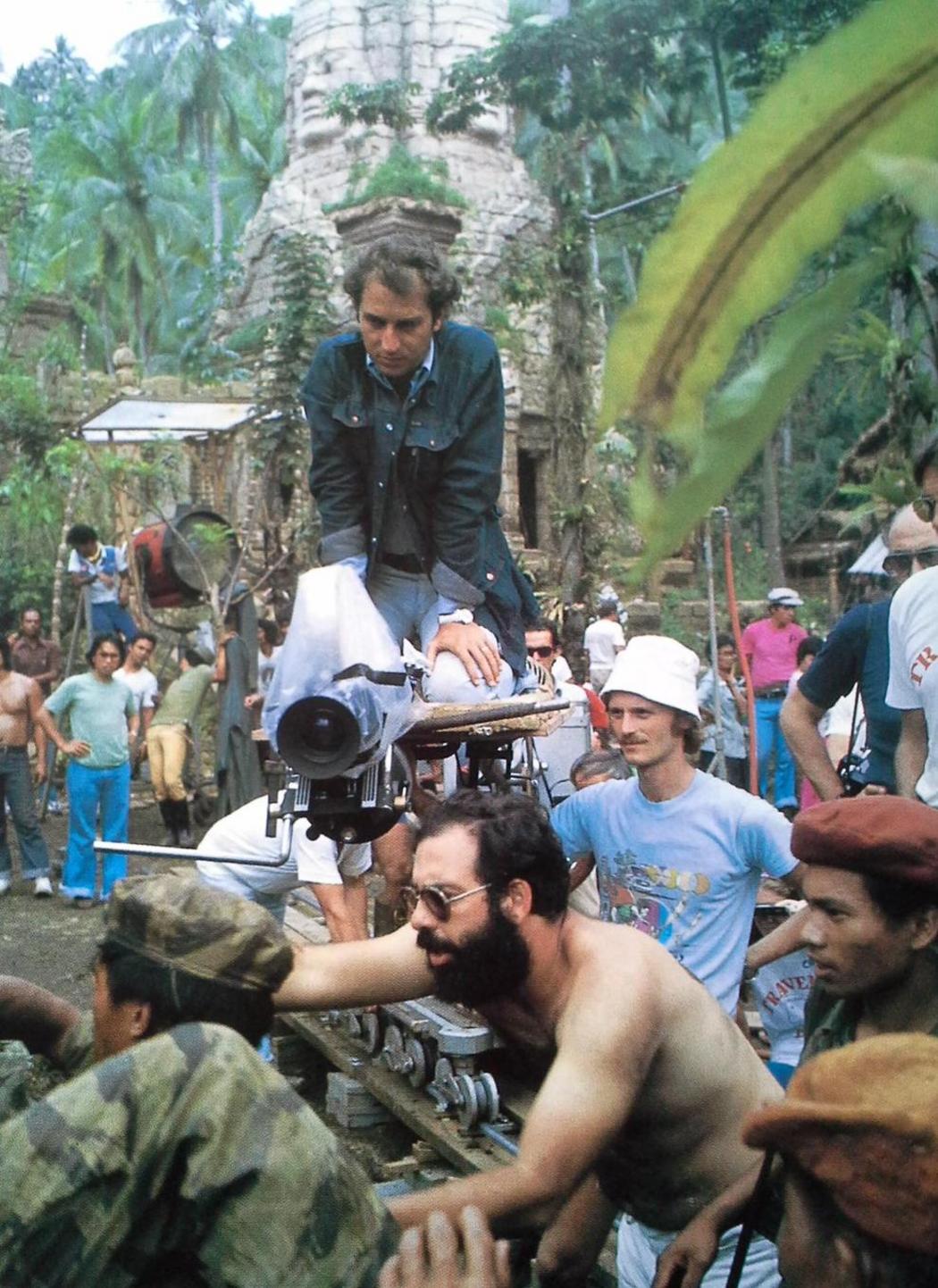

There are only a handful of cinematographers in the world whom we could even place in the same sentence as Vittorio Storaro. The legendary Italian director of photography is one of the most respected artists in his line of work: a three-time Oscar Winner (Apocalypse Now, Reds, The Last Emperor), Bernardo Bertolucci’s close collaborator (Last Tango in Paris, The Conformist, 1900, Luna, Little Budha), the receiver of ASC’s Lifetime Achievement award, a man who continues to work and transfer his knowledge to the next generation, as he was doing at the Camerimage International Film Festival this year, when we sat down to discuss his career and recent preoccupations. It goes without saying what kind of an honor it was to have a conversation with this giant of the filmmaking world, whose masterful work on Coppola’s classic Apocalypse Now, where he used colors to portray the psychological states of the characters, made us start paying closer attention and appropriate respect to the art and craft of cinematography. Mr. Storaro turned out to be a friendly and kind interviewee, patiently and gracefully tackling all of my questions, as I tried to get to know a thing or two about his beginnings and all the things that make him so good at what he does.

In your work you advocate the idea that color and light could and should be used to add emotional subtext to the story.

It’s not only my idea, it’s something that happens anyhow. Even if you don’t know. Wherever you put the camera, wherever you put your canvas to make a painting, the moment you use this kind of light, for example, you say something very specific. It is happening whether we know it or not, because of its energy. The main problem is if you know it or don’t. If you know the meaning, if you know the fact that natural light is energy, and what is energy? It’s a frequency of waves. Those waves arriving to us. Not only through eyes, but through our entire body. It’s scientifically proven that our blood pressure, our metabolism is changing according to the kind of vibration it receives. When you’re making a photograph, a painting or a film, and you use some kind of light or some kind of color, you’re sending a message. If you don’t know it, you’re doing it according to how you feel is right. But if you’re aware of it, if you studied the symbology, physiology, dramaturgy of light or color, you can use them like a musician using do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do. You’re using red, orange, yellow, blue, violet. That’s the point.

You stated many filmmakers today fail to use this.

Not that they’re failing, but they’re using it subconsciously. When you see in a film “cinematography by” or “director of photography,” whichever they were using, it’s that person responsible. In both the good and the bad ways. Sometimes I know what I’m doing, but I’m not necessarily able to express myself properly in order to reach the kind of emotion that I think would be correct for an audience to feel. That’s the way art is moving.

What’s your view on cinematography today?

Cinema is being called the tenth muse. Plato recognized the creative inspiration can arrive to us from different sources. Cleo, Melpomene, Urania, and so on. Modern visual art didn’t exist back then, obviously. Photography or cinematography or television, whatever. In modern times, cinema became the tenth muse. Why? Because it’s nourishing itself from literature, from architecture, music, philosophy… What that means is that even if you don’t know it, you have to deal with those elements. New technology brought to us the consciousness of making images. Today you have any still camera, any video camera, you push a button, things happen automatically. Today film students don’t know anymore how to realize an image. At the beginning, the so-called photographers had to practice, they had to study how to do it. The same thing was for cinematography. You grow up in learning how it’s possible to use a piece of mechanic and some chemistry to turn an idea into a realized image. Today, nobody knows. You don’t need to know. You push a button and get an image. What’s happening today is that people aren’t aware of how it was before.

With new technology today you can achieve an image in a very fast simple way, so you don’t even know how it’s being formed, what kind of meaning is in it. Video cameras today are very sensitive, they have 1000, 2000 ASA, which is a number that tells you their speed. At the beginning, the number was 16 or 25. So you had to know the use of light to make the image visible. Today they don’t know. Wherever they put the camera, you see an image. That’s it. They don’t interpret it. You need one kind of a scene, one kind of a visual concept, and in order to achieve those you have to use different kinds of light. That’s the problem today. There was a great poet, who was the father of Bernardo Bertolucci. His name was Attilio Bertolucci. One of the best poets in Italy. Being a poet, one day he said cinema lost its poetry the moment it got sound. Why? Because at the beginning, where there was no sound in films, in order to tell the story you had to be very conscious and ask questions like “should we do it like this or maybe like this,” which is the best way to tell the story. Today films become radio plays, theater plays, not cinema plays. They put some little soft light and you can record an image. That’s the tragedy of modern technology.

Bernardo Bertolucci influenced you greatly in the first phase of your career, as you said, in the times “before you lost your innocence.” What kind of an innocence are we talking about?

In the days before I first worked with an electronic camera. In the beginning I was lucky that my father was a projectionist in a theater and he was screening many, many films, many images. And in dreaming for me to become a part of those images, he pushed me to study photography and cinematography. I came out after studying photography for five years and studied cinematography for further four years. I thought I was very knowledgeable. But I was knowledgeable only in technology. Photography and cinematography schools mainly taught me about technology, they never taught me anything about the art. When I discovered this while watching a painting by Caravaggio, I realized I know nothing about this. That wasn’t only innocence. I was very arrogant, thinking I know everything. I realize now that I was very ignorant, and I tried to put together these two areas of knowledge. I started to read books, look at paintings, listen to music… to make some kind of a balance between these two. When we make movies and read the script, we visualize in our minds how it is possible to portray this verbal concept in the script into a visual concept on the screen. You try to think in terms of painting, photography or even philosophy to come up with the best way to represent it, and you present this idea to the director, and if he accepts, you perform it.

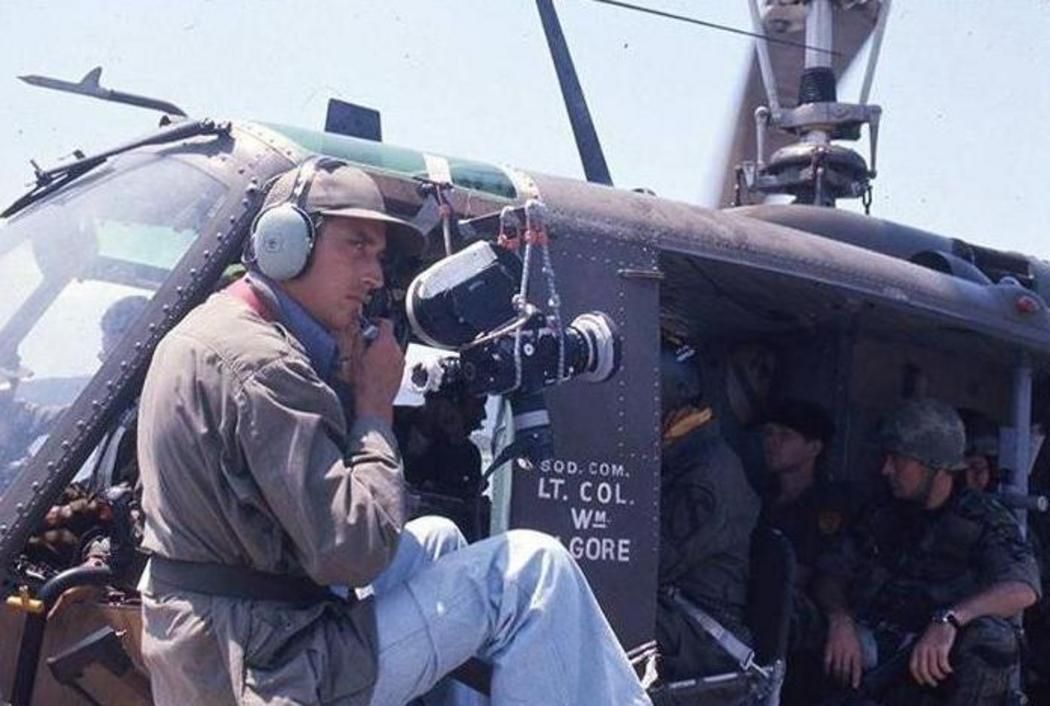

But you don’t know if you can reach that level, so you do whatever you can. When the laboratory gives you back the image, that’s when you see if you’ve succeeded. When I was working in the Philippines on Apocalypse Now, I sent the negatives all the way to Rome. They receive it, develop it, print it and send it back after two weeks. So the image I was thinking about two weeks before comes back to me two weeks later. I knew a lot in theory, in experience, in philosophy, but you’re never completely sure. Only when you finally see it can you say, okay, this is the image. Not only that, but the film needs to be edited, needs to be printed perfectly at the end, and only when you play it in the theater in front of the audience, and when the audience reacts to that image, only then do you know if your idea was conveyed to them. When I used one video camera from Sony in 1983 that came for experiment, the chance to use high definition compared to the normal definition that was used at the time, I turned on the camera, I look at the monitor and I see an image in color, in high definition, perfect. And I say, oh my God, now I know what I’m doing the moment I’m doing it. Now I can see what I’m thinking. If I see the image is no good, I move it a little, adjust it. You see what you are thinking. There I lost my innocence. Now I’m conscious, now I know perfectly what I’m doing in this moment.

With the rise of digital technology, to what degree has the working relationship between the cinematographer and the director changed?

Change depends on your level, on your relationship with the director. The cinematographer used to pretend to be the only person on the set who knew what the image looked like after it was developed at the laboratory. Not always true, because each one of us according to his experience, his knowledge, each one of us could imagine what the image looked like. But there were many elements in between, the kind of registration through the lens, the film, the laboratory, the interpretation of the technician, quality of the projector… From the moment new technology came out, from the moment you see the image at the same time, you lost this kind of pretence that nobody knows what the image is like but you. Everybody can see. So what is the major difference today? It’s not that you have to prepare yourself so much for the technology, because somebody can always help you with it, like a digital technician. The knowledge of the meaning of the visual art. If you know how to cause a certain emotion or reaction with the use of light, you are able to convey the message of the meaning of the shot according to the script, in the proper way. More than anybody else. Even if the director sees the image and tells you, “ah, Vittorio, I don’t think it’s appropriate, maybe I need this kind of neutral light between this part and this part,” you can discuss it with him, explain it, talk about how you can change it according to the image. So you need to know not only technology, but also the meaning of visual art, so you could use this knowledge. You have to study the philosophy to be good in practice.

What initially attracted you to the world of film? Was there a specific film you watched as a child?

Without any doubt, it was my father. The first movie I saw was when I was seven or eight years old. Not that it necessarily moved me in the direction of cinema, but the first image I remember was the image of City Lights from Charlie Chaplin. But after that I went to work with my father several times, and as a child I was watching what he was screening, and in this way I saw many, many films. Italian films, in particular. Through the projectionist booth. There’s no doubt it was then I started to become influence by the moving images, and later I went on to study it.

When your father pushed you in this direction, you didn’t mind?

I didn’t have any other thoughts about what to do. I was very young, I was eleven years old when he sent me to the photography school. But step by step it also became my own dream.

You’re still incredibly productive. Has the passion for visual storytelling remained the same?

Without doubt you become more aware. I lost my innocence, I’m much more conscious, much more mature. But in every movie I start, even if I have much more experience and knowledge of theory, more solid ground, but you never know what door you are opening with this new story, the kind of journey you are about to undertake. It doesn’t matter how prepared you are, the only thing you know is where you start, but never where you’re going to finish. That’s fantastic because it’s always exciting to discover where you’re heading. You have to recognize, when you first meet with a director, if the kind of journey he wants to do is similar to the kind of journey you want to go. That’s why I actually made films with very few directors.

A marvelous documentary about legendary cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, one of history’s ten most influential cinematographers. Storaro talks about his work, along with collaborators like Warren Beatty, Francis Ford Coppola, Bernardo Bertolucci and peers like Néstor Almendros. On-set footage from Dick Tracy and Apocalypse Now. Storaro explains his theories about light and colour, and gives a potted history of lighting in the cinema.

An interview conducted by Sven Mikulec. Still photographers (Apocalypse Now): Chas Gerretsen, Josh Weiner, David Jones, and Dick White © Zoetrope Studios, United Artists. Featuring highlights from the Margaret Herrick Library and the Academy Film Archive.

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or click on the icon below:

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in

[newsletter]