By Sven Mikulec

After making Rashomon in 1950, Akira Kurosawa set his eyes on making a film based on William Shakespeare’s ‘Macbeth.’ Since Orson Welles’ version was announced somewhere around that time, he decided to put it on hold, switched his attention to other projects and returned to the idea in the second half of the decade. In 1957, he finally made Throne of Blood, a film mostly ignored by the Western audiences at the time, but a marvelous piece of filmmaking that would soon acquire the reputation of one of the all-time best film adaptations of the world’s most celebrated poet’s work. Interestingly enough, Kurosawa wrote the screenplay with the intention of hiring another director to actually make the film, while he would take on the producer’s role.

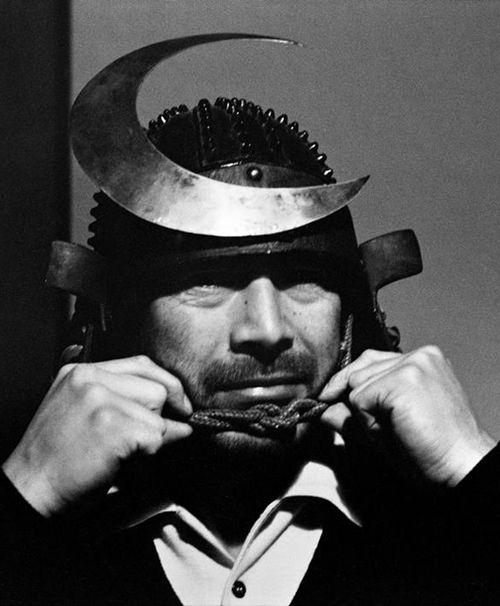

When Toho Studios realized the potential expenses of making such a film, they asked Kurosawa to shoot it himself. Keeping the same core of the original play, which is sometimes simply called The Scottish Play due to the superstition surrounding its cursed status, Kurosawa took a lot of liberties with the material, and this turned out to be one of the film’s greatest assets. By transferring Shakespeare’s work to 16th century Japan, Kurosawa created a unique and mesmerizing mix of Western and Japanese cultures. To be more precise, Throne of Blood could be called the mixture of two distinct aesthetics: the aesthetics of the Western and that of the traditional Japanese Noh Theatre. Noh or Nogaku is a form of classical Japanese musical drama performed since the 14th century and is considered the oldest major theater art still performed these days, and is distinguished by the use of stylized masks functioning as the primary visual means for conveying emotions.

The same approach was used by Kurosawa, as the faces of his characters heavily echo this practice. While in ‘Macbeth’ it’s open to interpretation to what degree free will influences the course of an individual’s life, as opposed to some kind of divine will, Kurosawa settled for a less ambiguous interpretation. Describing himself as an ordinary man observing both the history of Japan and the contemporary society he was a part of, Kurosawa chose to explore the theme of greed, corruption and ambition, the never-ceasing and ultimately self-destructing hunger for power he felt functioned in a cyclical form, constantly repeating itself along with all of it destructive consequences over and over again. He finds the fault not in the sky: his protagonist isn’t just an actor, a pawn performing the lines written in the stars.

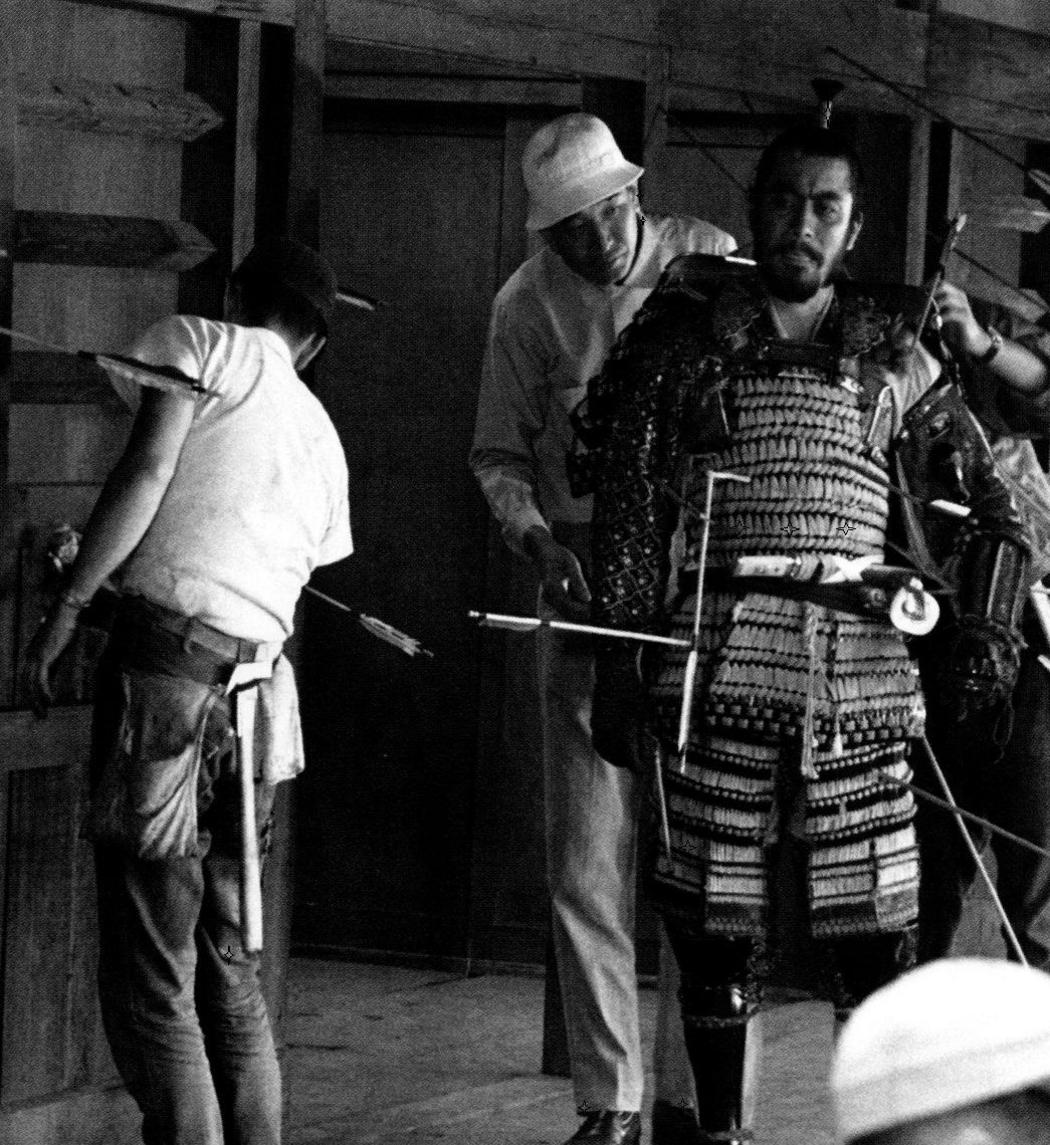

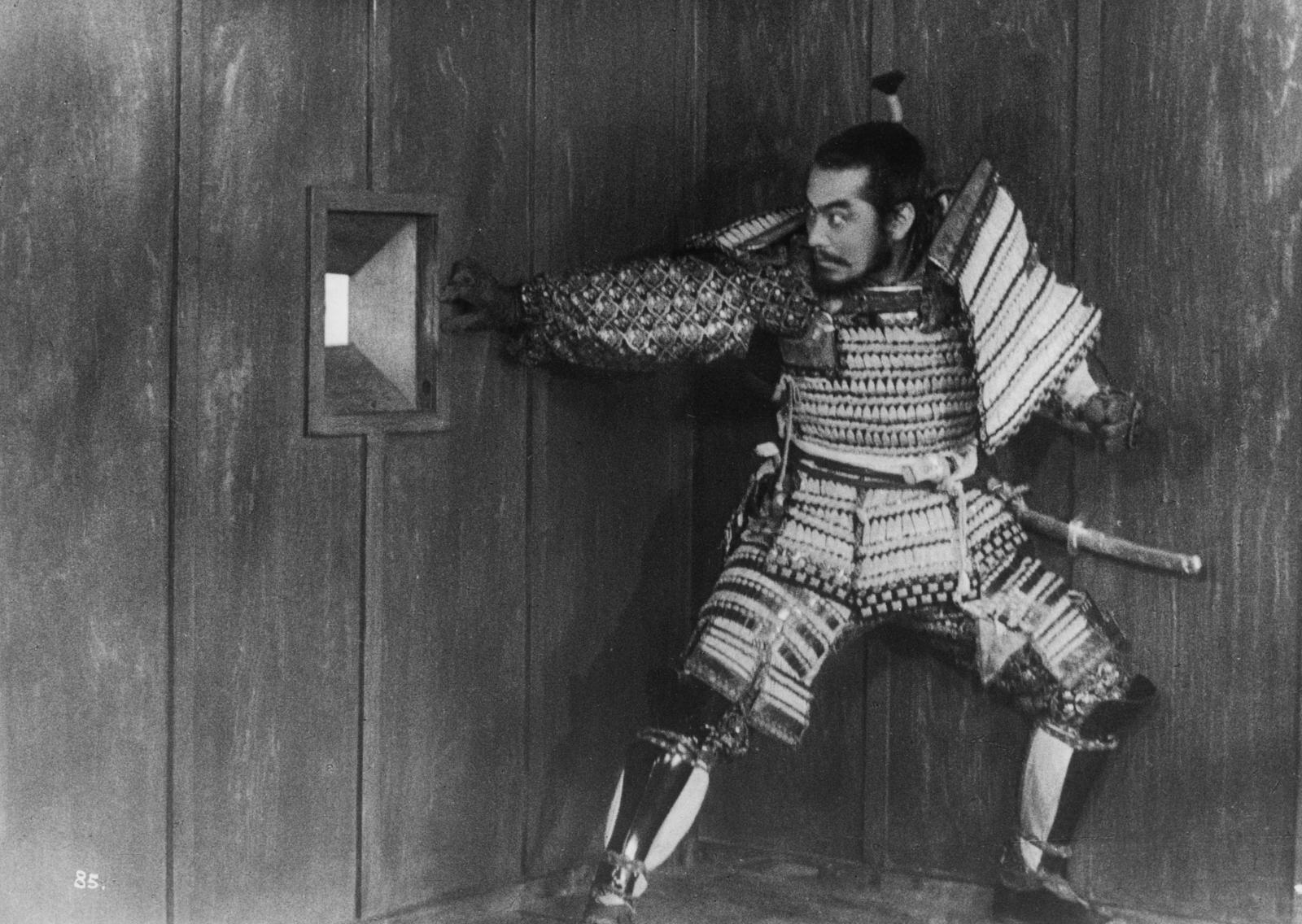

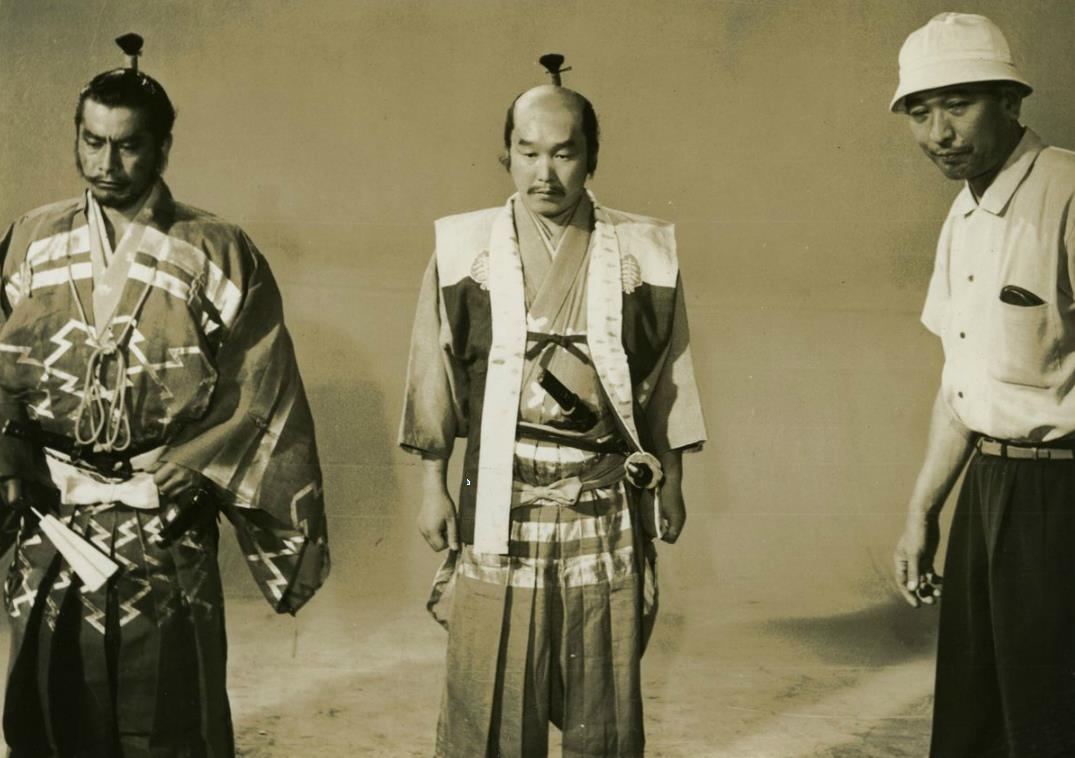

His ultimate demise is the direct consequence of his inner self, his nature and the classic cautionary tale of the ancient wisdom that says that when we strive to prevent something from happening with all our energy and power, it’s our actions that usually make the wretched thing happen. Kurosawa’s Macbeth is called Taketoki Washizu (played by the brilliant Toshirô Mifune, the filmmaker’s greatest and most reliable acting collaborator), a skilled general who starts believing in a prophecy he would become the ruler and following his ambitious, manipulative wife Asaji’s (the great Isuzu Yamada) advice and urging. Both Washizu and Asaji slowly get consumed by the psychological consequences of their gruesome actions, with her descent into madness and his inevitable demise in one of the best death scenes in the history of film.

Throne of Blood seems cold, distant, presenting characters we’re not supposed to sympathize with. Kurosawa shot the film as something the audience should look at and absorb a lesson, not become a part of the story by entering the minds of the persons whose life paths they witness. Because of this, it’s easy to say Throne of Blood is a cautionary tale, but such a classification is used without any ounce of intention of belittling its quality and greatness. It’s a visual spectacle, with the castle exteriors built high up on the slopes of Mount Fuji, where heavy fog and black volcanic dirt were practically regular inhabitants.

The film was shot by cinematographer Asakazu Nakai, with whom Kurosawa worked on Seven Samurai and would later reunite for Ran, another one of his great Shakespeare adaptations. Throne of Blood was shot in black-and-white, with the contrasts, omnipresent fog, expressionless faces and visual symbolism creating the feeling that what you’re actually watching is someone’s own personal nightmare. Yoshiro Muraki, the production designer, explained the design of the castle was based on ancient Japanese scrolls, with the color black chosen for the walls and armor added to complement the general visual style of the film. The screenplay was co-written by Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto, Hideo Oguni and Ryûzô Kikushima, with Toho Studios regular and Kurosawa’s favorite composer Masaru Satô delivering the score, while the director himself edited the picture.

Kurosawa’s film was hailed by a number of prominent film and literary critics from all corners of the world. The American literary critic Harold Bloom called it the most successful film version of ‘Macbeth,’ the poet T. S. Elliot stated it was his favorite film, Time magazine cited it as the most brilliant and original attempt ever made to put Shakespeare in pictures, while the critics universally appreciated its values. Throne of Blood is definitely one of the most haunting, beautiful and original adaptations we’ve seen, and even if Orson Welles, Roman Polanski or Justin Kurzel’s variants of this story are closer to what you believe to be a perfect version of ‘Macbeth’ on film, it’s impossible to shake off the value of Kurosawa’s grandiose effort. Throne of Blood is a moody, intense, poetically shot movie that history will remember as one of the Japanese master’s best.

The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available from the Criterion Collection and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

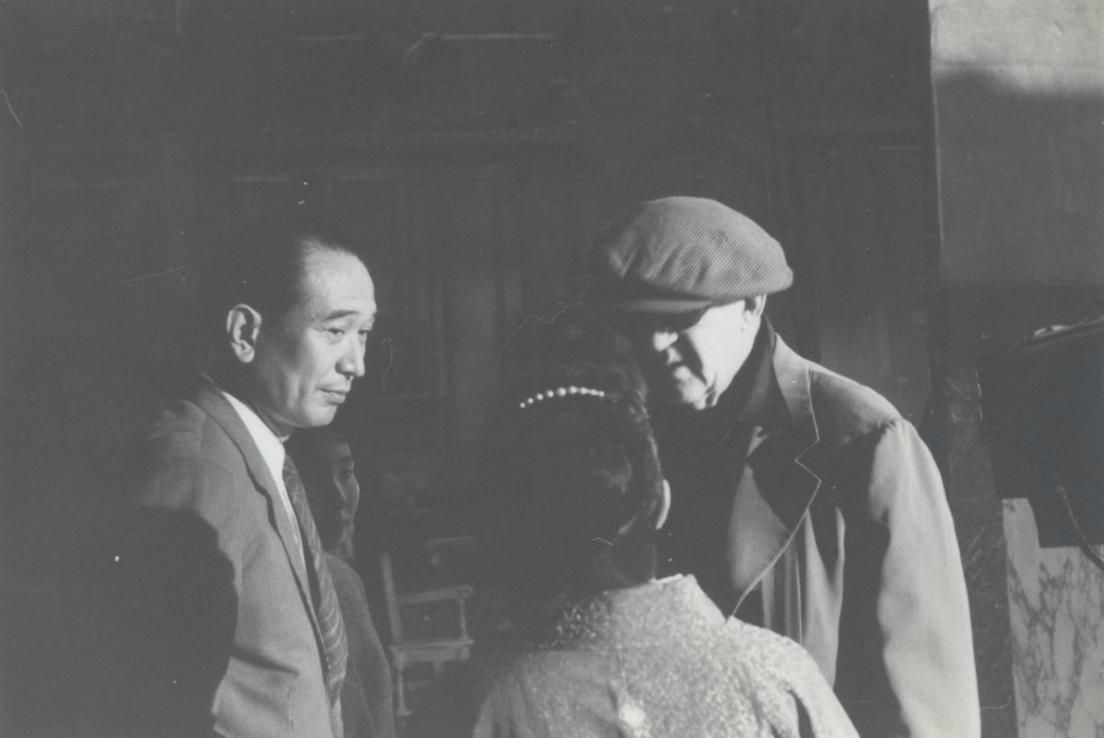

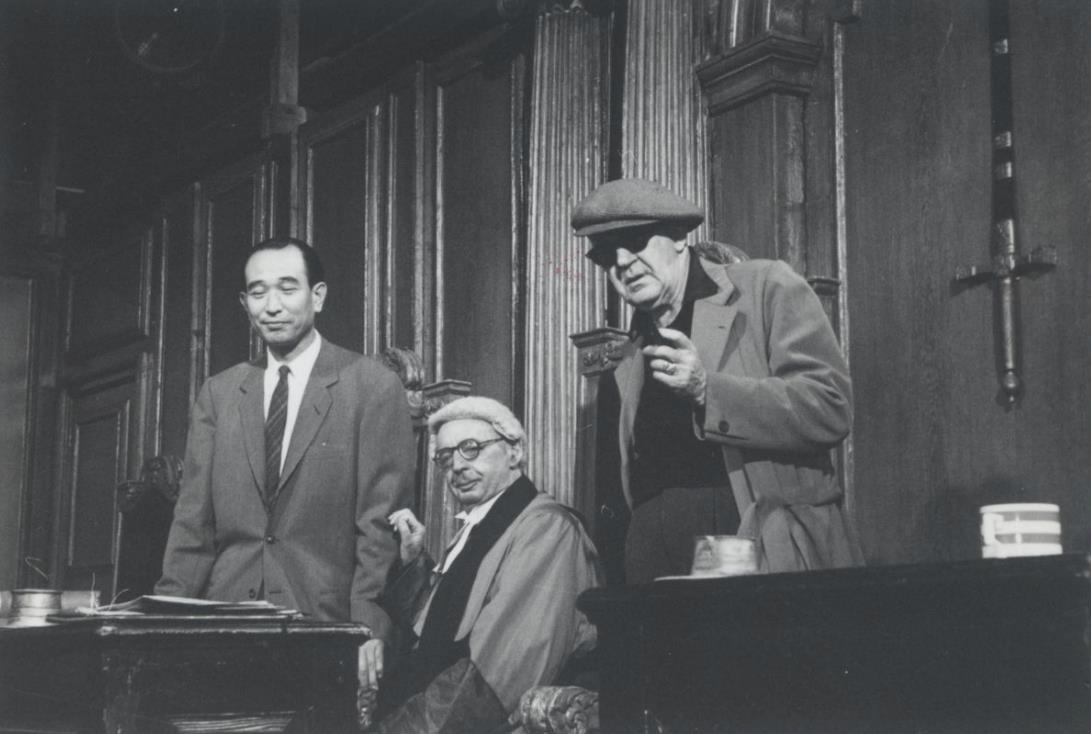

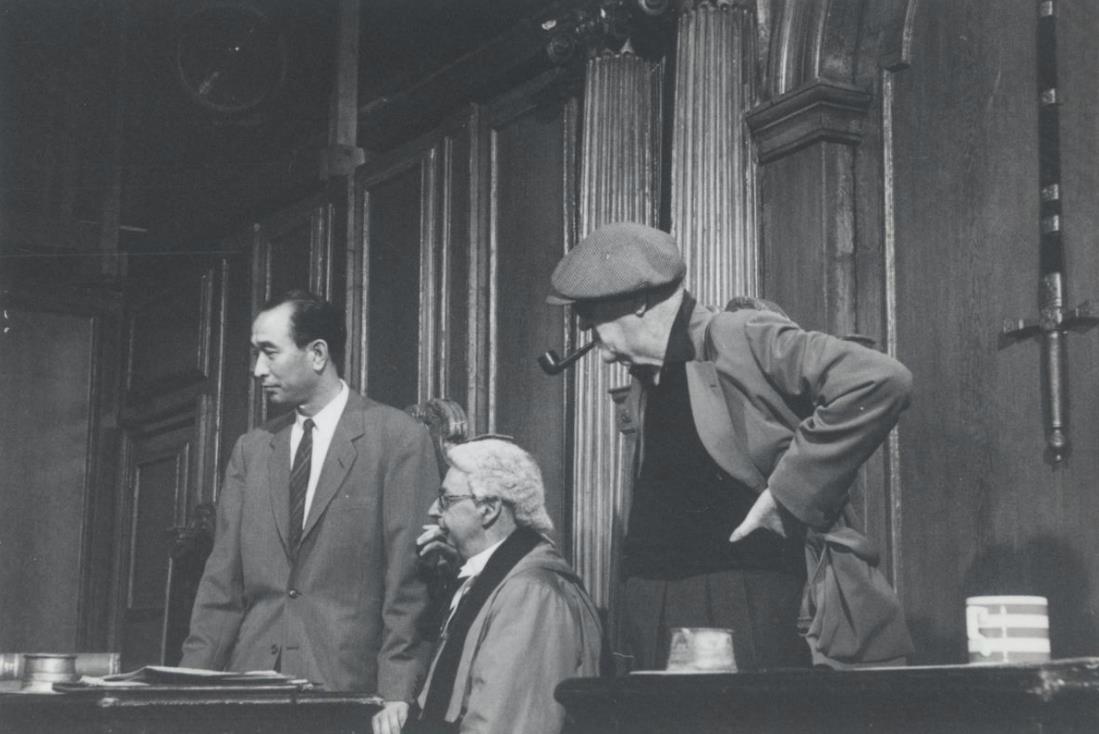

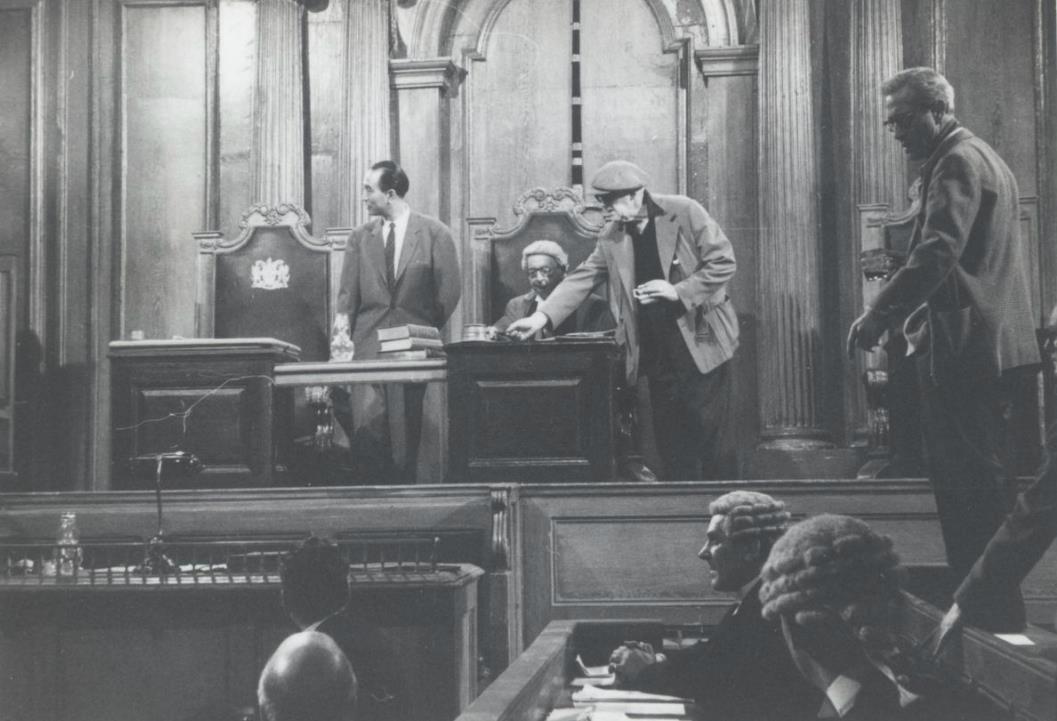

In October 1957, Akira Kurosawa made his first trip abroad for a screening of Throne of Blood at the opening of London’s National Film Theatre (NFT, now BFI Southbank). There he met the likes of René Clair, Vittorio De Sica, Laurence Olivier, Gina Lollobrigida, and one of his greatest inspirations as a filmmaker, John Ford. Kurosawa’s longtime assistant and collaborator, Teruyo Nogami, describes the event as recounted to her many times by Kurosawa.

It was the day of the award presentation at NFT. In his anteroom, Kurosawa waited nervously. One reason for his nervousness was his getup—for the first time in his life he was wearing formal Japanese attire: crested kimono, baggy pleated trousers known as hakama, zori sandals. What added to his nervousness was that no interpreters were allowed in the room… John Ford came up, thumped him on the back, said, “John Ford,” and shook hands, then jerked his thumb as if to say, come this way. In broken Japanese, Ford invited Kurosawa to have a drink. Before the award ceremony, Ford made gestures to indicate his heart was pounding with nervousness, and then did warm-up stretches until De Sica teasingly threw a handkerchief at him from the side. Thanks to Ford, Kurosawa was able to relax a bit even though he knew no English… The following day he went to call on Ford, who was then filming Gideon’s Day in the MGM studios. On stage, Ford seated Kurosawa in a chair that he had brought out and placed next to the camera. When the take was finished, he told Kurosawa “Arigato” (Thank You) and bowed. Then he turned to the cast and crew and introduced Kurosawa in a loud voice. Everyone saw him off with thunderous applause. Kurosawa told us that the tribute had moved him to tears.

Kurosawa himself recalled the meeting in a 1991 interview.

Ford treated me with affection; he used to call me Akira. I first met him decades ago when I was in Britain to receive an award for Throne of Blood at the London International Film Festival. Ford was in England shooting a picture, and I went to see him on location. He saw me, and straight off he said, in heavily accented Japanese, ‘I need a drink!’ Ford could speak a little Japanese… Once when I was having a quiet drink, he came up to me and asked what the heck I was drinking. ‘Wine,’ I told him, to which he said, ‘No, no! You’ve got to drink scotch!’ and brought me a bottle. Seriously, though, he was really good to me.

Newsreel footage from the evening can be seen here courtesy of British Pathé. Courtesy of Akira Kurosawa.

“Kurosawa does not like to talk about his films, nor is he fond of discussing film theory. Once, when I ask him about the meaning of one of his pictures, he said: ‘If I could have said it in words, I would have—than I wouldn’t have needed to make the picture.’ Recently, however, Kurosawa expressed an interest in looking back over the body of his work, and these are the results. I have deleted nothing and have only added to the material when it seemed relevant.” —Donald Richie, Kurosawa on Kurosawa, Sight and Sound

PRODUCTION

Kurosawa did not intend this film for himself. “Originally, I wanted merely to produce the picture and let someone younger direct it. But when the script was finished and Toho saw how expensive it would be, they asked me to direct it. So I did. My contract expired after these next three films anyway.” Perhaps if he had written the script with himself in mind he might have written it differently. He has said that the scripts he does for others are usually much richer in visuals than those he does for himself—and The Throne of Blood is visually extremely rich. But what occurred, he says, is that he often visualized scenes differently from the way he had written them. Not that he improvised, or invented on the set. “I never do that. I tried it once. Never again. I had to throw out all of the impromptu stuff.” What he did do, once he knew he was to direct the picture, was to begin a study of the traditional Japanese tnusha^e—those early picture scrolls of battle scenes. At the same time he asked Kohei Esaki—famous for continuing this genre—to be the art consultant. The designer, Yoshiro Muraki, remembers: “We studied old castle layouts, the really old ones, not those white castles we still have around. And we decided to use black and armored walls since they would go well with the suiboku’ga (ink^painting) effect we planned with lots of mist and fog. That also is the reason we decided that the locations should be high on Mount Fuji, because of the fog and the black volcanic soil. But… we created something which never came from any single historical period. To emphasize the psychology of the hero, driven by compulsion, we made the interiors wide with low ceilings and squat pillars to create the effect of oppression.”

Kurosawa remembers that “first, we built an open set at the base of Fuji with a flat castle rather than a real three-dimensional one. When it was ready, it just didn’t look right. For one thing, the roof tiles were too thin and this would not do. I insisted and held out, saying I could not possibly work with such limitations, that I wanted to get the feeling of the real thing from wherever I chose to shoot.” Consequently, Toho having learned from Seven Samurai onward that Kurosawa would somehow get his way, the entire open set was dismantled. “About sets,” Kurosawa has admitted: “I’m on the severe side. This is from Ikiru onward. Until then we had to make do with false-fronts. We didn’t have the material. But you cannot expect to get a feeling of realism if you use, for example, cheap new wood in a set which is supposed to be an old farm-house. I feel very strongly about this. After all, the real life of any film lies just in its being as true as possible to appearances.”

After a further argument with Ezaki, who wanted a high and towering castle while Kurosawa wanted a low and squat one, the set eventually used was built—to Kurosawa’s specifications (which were extreme: even the lacquer-ware had to be especially made, from models which he found in museums). “It was a very hard film to make. I decided that the main castle set had to be built high up on Fuji and we didn’t have enough people and the location was miles from Tokyo. Fortunately there was a U.S. Marine Corps base nearby and they helped a lot. We all worked very hard, clearing the ground, building the set, and doing the whole thing on this steep, fog-bound slope. An entire MP battalion helped most of the time. I remember it absolutely exhausted all of us—we almost got sick.” Actually, only the castle exteriors were shot here. The castle courtyard (with volcanic soil brought all the way from Fuji so that the ground would match) was constructed at Toho’s Tamagawa studios in the suburbs, and the interiors were shot in a smaller Tokyo studio. In addition, the forest scenes were a combination of actual Fuji forest and studio in Tokyo, and Washizu’s mansion was miles away from anywhere, in the Izu peninsula.

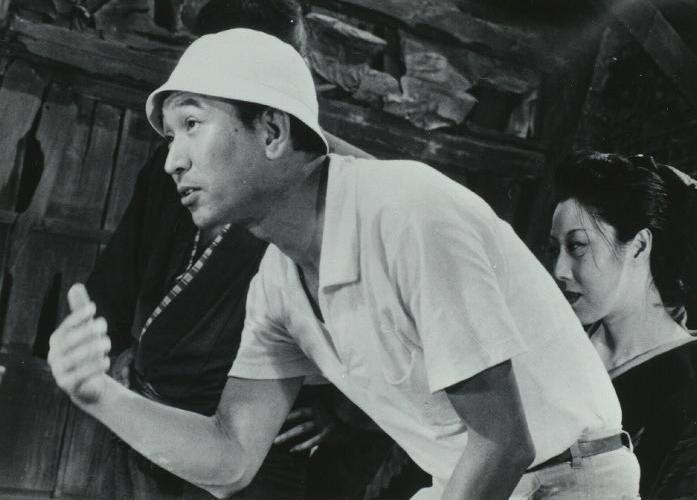

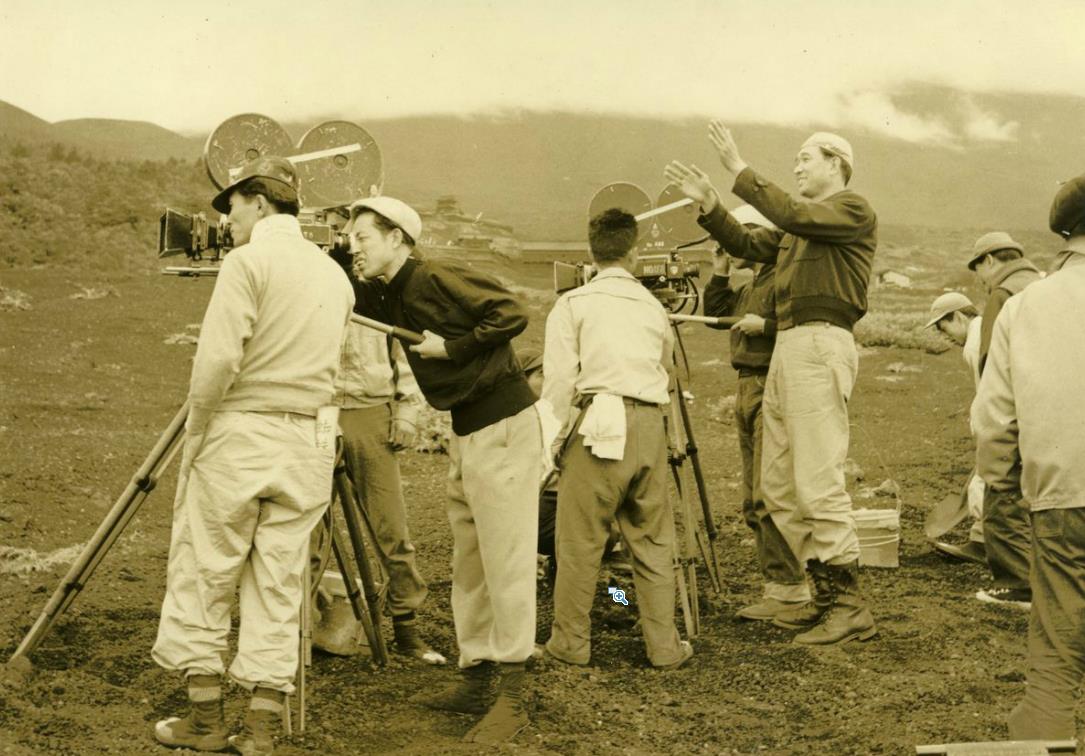

I remember this set particularly. Like all the others it was completely three dimensional and was, in effect, a real mansion set in the midst of rice paddies in an almost inaccessible valley. I remember it particularly because I was there when Kurosawa visualized a scene. Though it was in the script, there had been little indication as to how it would be seen and, after some thought the night before, Kurosawa had decided. The scenes included those where a messenger comes announcing the arrival of the lord and his hunting party. Washizu, already thinking of murder, rushes out of his mansion, astonished that fortune should at this time direct that the lord appear for the night. The first camera was on a platform inside the mansion gates, and the second was located in the rice-field outside, the two cameras hidden from each other by an angle in the wall. Kurosawa was on the platform, looking through the finder, and selecting the angle he thought best. There was one rehearsal and then the take. From the far distance, the messenger galloped up on horseback and announced the lord. The castle retainers rushed out of the gate and the scene was stopped because one of them slipped and fell down. “A little too much atmosphere,” said Kurosawa, everyone laughed, and the scene was re-shot.

The main camera was taking this scene from inside the gates, while the auxiliary camera was taking it from the side. The next scene, a continuation of the first, shot the messenger giving his message and the main camera was equipped with long-distance lenses. After this was shot, the two cameras, both with long-distance lenses, shot the distant hunting party (complete with deer and boar, an enormous procession) advancing. The next shot in this small sequence was to show Mifune rushing out as the distraught Washizu. Mifune practiced running back and forth to get himself properly winded, and the take was made, with both cameras panning with him, one with long-distance lenses. Then more scenes were taken of the advancing hunting party, its number now swelled by all the neighborhood farmers that the production chief could find costumes for. Particularly fine were those rushes of the advancing hunting party, both the long silhouette shots and, later, the advance, taken with long-distance lenses which flattened the figures out and looked like a medieval tapestry. After they were taken Kurosawa said he was pleased. “I have about ten times more than I need.”

In the finished film this morning’s work takes ten seconds. Gone are the living tapestries (“they only held up the action”) ; the wonderful turning shots of the messenger (“I don’t know—they looked confused to me”) ; a splendid entrance of Mifune skidding to a stop (“you know, Washizu wasn’t that upset”); and a lovely framing shot of the procession seen through the gate (“too pretty”). I still think of Kurosawa that morning, up on his platform, directing everything, always quiet, suggesting rather than commanding, looking through the view-finders, getting down to run through the mud to the other camera, making jokes, getting just what he wanted. And then—having the courage, the discipline to choose from that morning’s richness just these few frames which contained what would best benefit the film. And, all the time, making the definitive statement on man’s solitude, his ambition, his self’betrayal. —The films of Akira Kurosawa by Donald Richie

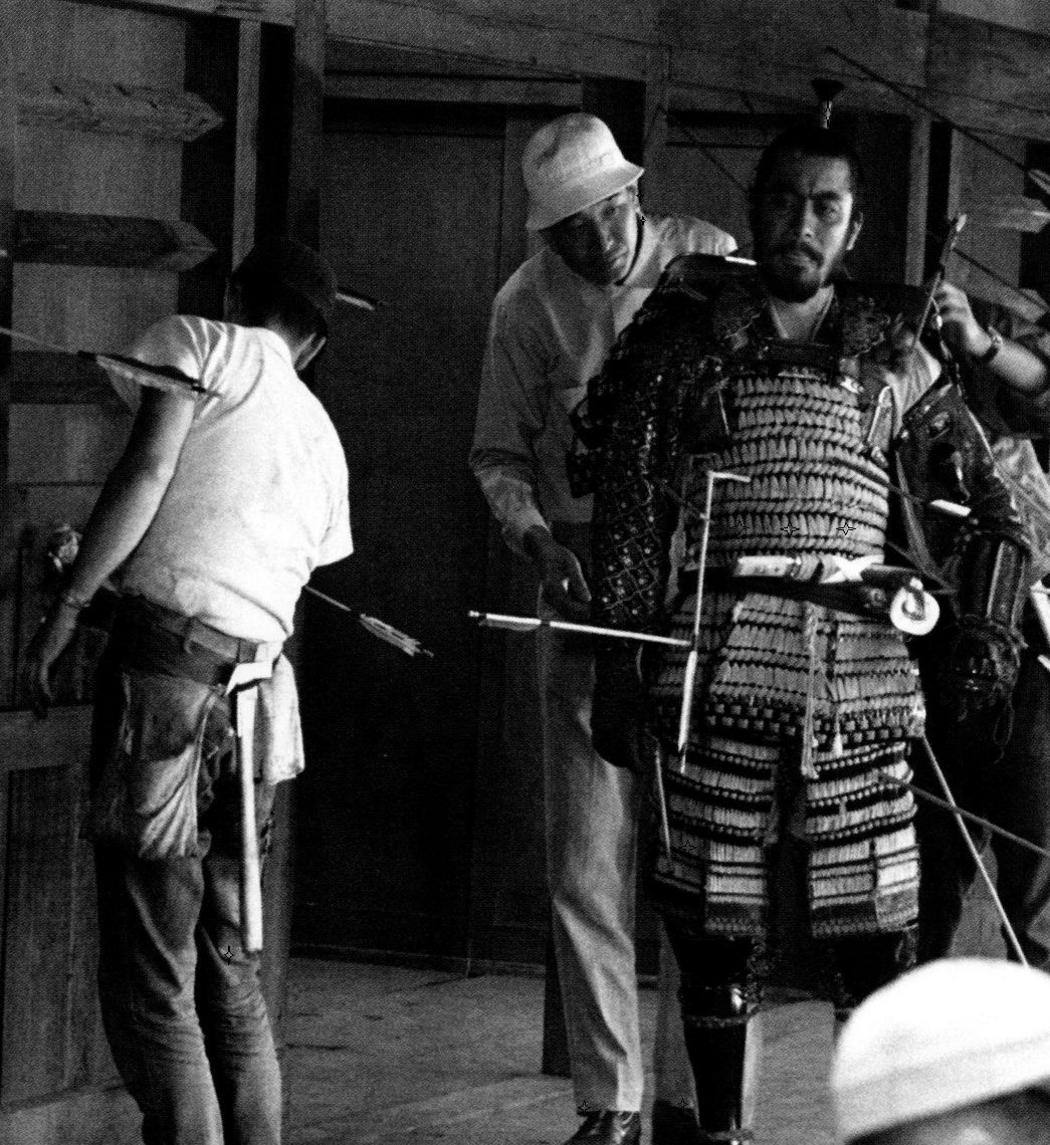

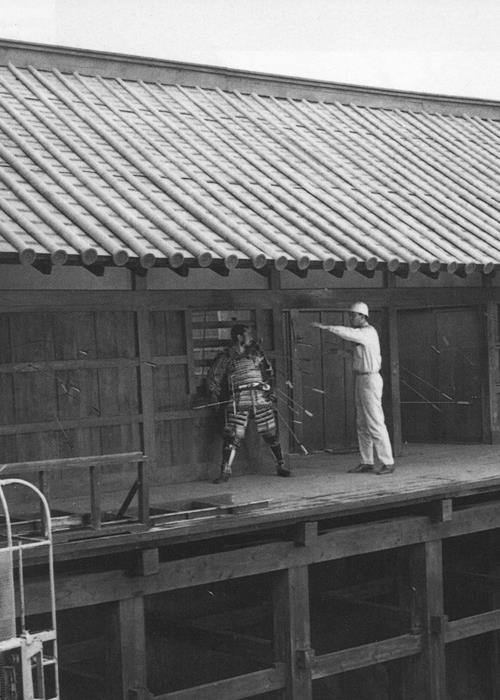

It’s impossible to watch the unforgettable climax of Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood and not wonder, How’d they do that? Spoilers ahead: In the scene, Toshiro Mifune’s ruthless warrior, modeled on Shakespeare’s Macbeth, finally gets his comeuppance in the form of a shower of arrows. Some narrowly miss him, others, well, do not. To get some insight into how Kurosawa, his crew, and, of course, Mifune, accomplished this, check out this short clip from a supplement on Criterion’s new edition of the film, taken from the Toho Masterworks series Akira Kurosawa: It Is Wonderful to Create. In it, the film’s set decorator and prop master Koichi Hamamura fills us in some of the tricks of the trade (yes, those were real arrows), as well as the suitably terrified star’s response to having acted out this ambitious, violent denouement.

In October 1990, Gabriel García Márquez visited Tokyo during the shooting of Akira Kurosawa’s penultimate feature, Rhapsody in August. García Márquez, who spent some years in Bogota as a film critic before penning landmark novels such as ‘One Hundred Years of Solitude’ and ‘Love in the Time of Cholera,’ spoke with Kurosawa for over six hours on a number of subjects. Below is a partial transcription of the conversation, first published by the Los Angeles Times in 1991.

I don’t want this conversation between friends to seem like a press interview, but I just have this great curiosity to know a great many other things about you and your work. To begin with, I am interested to know how you write your scripts. First, because I am myself a scriptwriter. And second, because you have made stupendous adaptations of great literary works, and I have many doubts about the adaptations that have been made or could be made of mine.

When I conceive an original idea that I wish to turn into a script, I lock myself up in a hotel with paper and pencil. At that point I have a general idea of the plot, and I know more or less how it is going to end. If I don’t know what scene to begin with, I follow the stream of the ideas that spring up naturally.Is the first thing that comes to your mind an idea or an image?

I can’t explain it very well, but I think it all begins with several scattered images. By contrast, I know that scriptwriters here in Japan first create an overall view of the script, organizing it by scenes, and after systematizing the plot they begin to write. But I don’t think that is the right way to do it, since we are not God.Has your method also been that intuitive when you have adapted Shakespeare or Gorky or Dostoevsky?

Directors who make films halfway may not realize that it is very difficult to convey literary images to the audience through cinematic images. For instance, in adapting a detective novel in which a body was found next to the railroad tracks, a young director insisted that a certain spot corresponded perfectly with the one in the book. “You are wrong,” I said. “The problem is that you have already read the novel and you know that a body was found next to the tracks. But for the people who have not read it there is nothing special about the place.” That young director was captivated by the magical power of literature without realizing that cinematic images must be expressed in a different way.Can you remember any image from real life that you consider impossible to express on film?

Yes. That of a mining town named Ilidachi, where I worked as an assistant director when I was very young. The director had declared at first glance that the atmosphere was magnificent and strange, and that’s the reason we filmed it. But the images showed only a run-of-the-mill town, for they were missing something that was known to us: that the working conditions in (the town) are very dangerous, and that the women and children of the miners live in eternal fear for their safety. When one looks at the village one confuses the landscape with that feeling, and one perceives it as stranger than it actually is. But the camera does not see it with the same eyes.The truth is that I know very few novelists who have been satisfied with the adaptation of their books for the screen. What experience have you had with your adaptations?

Allow me, first, a question: Did you see my film Red Beard?I have seen it six times in 20 years and I talked about it to my children almost every day until they were able to see it. So not only is it the one among your films best liked by my family and me, but also one of my favorites in the whole history of cinema.

Red Beard constitutes a point of reference in my evolution. All of my films which precede it are different from the succeeding ones. It was the end of one stage and the beginning of another.That is obvious. Furthermore, within the same film there are two scenes that are extreme in relation to the totality of your work, and they are both unforgettable; one is the praying mantis episode, and the other is the karate fight in the hospital courtyard.

Yes, but what I wanted to tell you is that the author of the book, Shuguro Yamamoto, had always opposed having his novels made into films. He made an exception with Red Beard because I persisted with merciless obstinacy until I succeeded. Yet, when he had finished viewing the film he turned to look at me and said: “Well it’s more interesting than my novel.”

Why did he like it so much, I wonder?

Because he had a clear awareness of the inherent characteristics of cinema. The only thing he requested of me was that I be very careful with the protagonist, a complete failure of a woman, as he saw her. But the curious thing is that the idea of a failed woman was not explicit in his novel.Perhaps he thought it was. It is something that often happens to us novelists.

So it is. In fact, upon seeing the films based on their books, some writers say: “That part of my novel is well portrayed.” But they are actually referring to something that was added by the director. I understand what they are saying, because they may see clearly expressed on the screen, by sheer intuition on the part of the director, something they had meant to write but had not been able to.It is a known fact: “Poets are mixers of poisons.” But, to come back to your current film, will the typhoon be the most difficult thing to film?

No. The most difficult thing was to work with the animals. Water serpents, rose-eating ants. Domesticated snakes are too accustomed to people, they don’t flee instinctively, and they behave like eels. The solution was to capture a huge wild snake, which kept trying with all its might to escape and was truly frightening. So it played its role very well. As for the ants, it was a question of getting them to climb up a rosebush in single file until they reached a rose. They were reluctant for a long time, until we made a trail of honey on the stem, and the ants climbed up. Actually, we had many difficulties, but it was worth it, because I learned a great deal about them.Yes, so I’ve noticed. But what kind of film is this that is as likely to have problems with ants as with typhoons? What is the plot?

It is very difficult to summarize in a few words.Does somebody kill somebody?

No. It’s simply about an old woman from Nagasaki who survived the atomic bomb and whose grandchildren went to visit her last summer. I have not filmed shockingly realistic scenes which would prove to be unbearable and yet would not explain in and of themselves the horror of the drama. What I would like to convey is the type of wounds the atomic bomb left in the heart of our people, and how they gradually began to heal. I remember the day of the bombing clearly, and even now I still can’t believe that it could have happened in the real world. But the worst part is that the Japanese have already cast it into oblivion.What does that historical amnesia mean for the future of Japan, for the identity of the Japanese people?

The Japanese don’t talk about it explicitly. Our politicians in particular are silent for fear of the United States. They may have accepted Truman’s explanation that he resorted to the atomic bomb only to hasten the end of the World War. Still, for us, the war goes on. The full death toll for Hiroshima and Nagasaki has been officially published at 230,000. But in actual fact there were over half a million dead. And even now there are still 2,700 patients at the Atomic Bomb Hospital waiting to die from the after-effects of the radiation after 45 years of agony. In other words, the atomic bomb is still killing Japanese.The most rational explanation seems to be that the U.S. rushed in to end it with the bomb for fear that the Soviets would take Japan before they did.

Yes, but why did they do it in a city inhabited only by civilians who had nothing to do with the war? There were military concentrations that were in fact waging war.

Nor did they drop it on the Imperial Palace, which must have been a very vulnerable spot in the heart of Tokyo. And I think that this is all explained by the fact that they wanted to leave the political power and the military power intact in order to carry out a speedy negotiation without having to share the booty with their allies. It’s something no other country has ever experienced in all of human history. Now then: Had Japan surrendered without the atomic bomb, would it be the same Japan it is today?

It’s hard to say. The people who survived Nagasaki don’t want to remember their experience because the majority of them, in order to survive, had to abandon their parents, their children, their brothers and sisters. They still can’t stop feeling guilty. Afterwards, the U.S. forces that occupied the country for six years influenced by various means the acceleration of forgetfulness, and the Japanese government collaborated with them. I would even be willing to understand all this as part of the inevitable tragedy generated by war. But I think that, at the very least, the country that dropped the bomb should apologize to the Japanese people. Until that happens this drama will not be over.That far? Couldn’t the misfortune be compensated for by a long era of happiness?

The atomic bomb constituted the starting point of the Cold War and of the arms race, and it marked the beginning of the process of creation and utilization of nuclear energy. Happiness will never be possible given such origins.I see. Nuclear energy was born as a cursed force, and a force born under a curse is a perfect theme for Kurosawa. But what concerns me is that you are not condemning nuclear energy itself, but the way it was misused from the beginning. Electricity is still a good thing in spite of the electric chair.

It is not the same thing. I think nuclear energy is beyond the possibilities of control that can be established by human beings. In the event of a mistake in the management of nuclear energy, the immediate disaster would be immense and the radioactivity would remain for hundreds of generations. On the other hand, when water is boiling, it suffices to let it cool for it to no longer be dangerous. Let’s stop using elements which continue to boil for hundreds of thousands of years.I owe a large measure of my own faith in humanity to Kurosawa’s films. But I also understand your position in view of the terrible injustice of using the atomic bomb only against civilians and of the Americans and Japanese colluding to make Japan forget. But it seems to me equally unjust for nuclear energy to be deemed forever accursed without considering that it could perform a great non-military service for humanity. There is in that a confusion of feelings which is due to the irritation you feel because you know Japan has forgotten, and because the guilty, which is to say, the United States, has not in the end come to acknowledge its guilt and to render unto the Japanese people the apologies due to them.

Human beings will be more human when they realize there are aspects of reality they may not manipulate. I don’t think we have the right to generate children without anuses, or eight-legged horses, such as is happening at Chernobyl. But now I think this conversation has become too serious, and that wasn’t my intention.We’ve done the right thing. When a topic is as serious as this, one can’t help but discuss it seriously. Does the film you are in the process of finishing cast any light on your thoughts in this matter?

Not directly. I was a young journalist when the bomb was dropped, and I wanted to write articles about what had happened, but it was absolutely forbidden until the end of the occupation. Now, to make this film, I began to research and study the subject and I know much more than I did then. But if I had expressed my thoughts directly in the film, it could not have been shown in today’s Japan, or anywhere else.Do you think it might be possible to publish the transcript of this dialogue?

I have no objection. On the contrary. This is a matter on which many people in the world should give their opinion without restrictions of any sort.Thank you very much. All things considered, I think that if I were Japanese I would be as unyielding as you on this subject. And at any rate, I understand you. No war is good for anybody.

That is so. The trouble is that when the shooting starts, even Christ and the angels turn into military chiefs of staff.

A Message from Akira Kurosawa: For Beautiful Movies (2000)—a 90-minute documentary that includes ten thematically separated interviews with Akira Kurosawa, filmed towards the end of his life. The director discusses his filmmaking and his quest for making the perfect, or “beautiful,” movie: “The documentary explores in-depth Akira Kurosawa’s approach to filmmaking. Divided into 10 chapters, the viewer journeys through the many stages of filmmaking—from ‘Cinematic Material’ to ‘Scripts,’ ‘Storyboards,’ ‘Shooting a Movie,’ and ‘Lighting,’ to ‘Art Direction,’ ‘Costumes,’ ‘Editing,’ ‘Music,’ and ‘Directing’—as Kurosawa discusses the insight he has gathered during his career. An idea for a film, he believed, was like a plant that forms naturally. He also placed much attention to his collaborators, listening to them while allowing them to see edits of the film in production in order to encourage their spirits. All that Kurosawa experienced was to lead him closer to his ideal of film, a realization of a “beautiful movie” founded in pure cinema, in which themes and messages were subordinate to the specific and artistic qualities of cinema. Dive into the depths of filmmaking with A Message from A Message from Akira Kurosawa: For Beautiful Movies, a masterclass in the art of cinema from one of its greatest artists.” —A-BitterSweet-Life

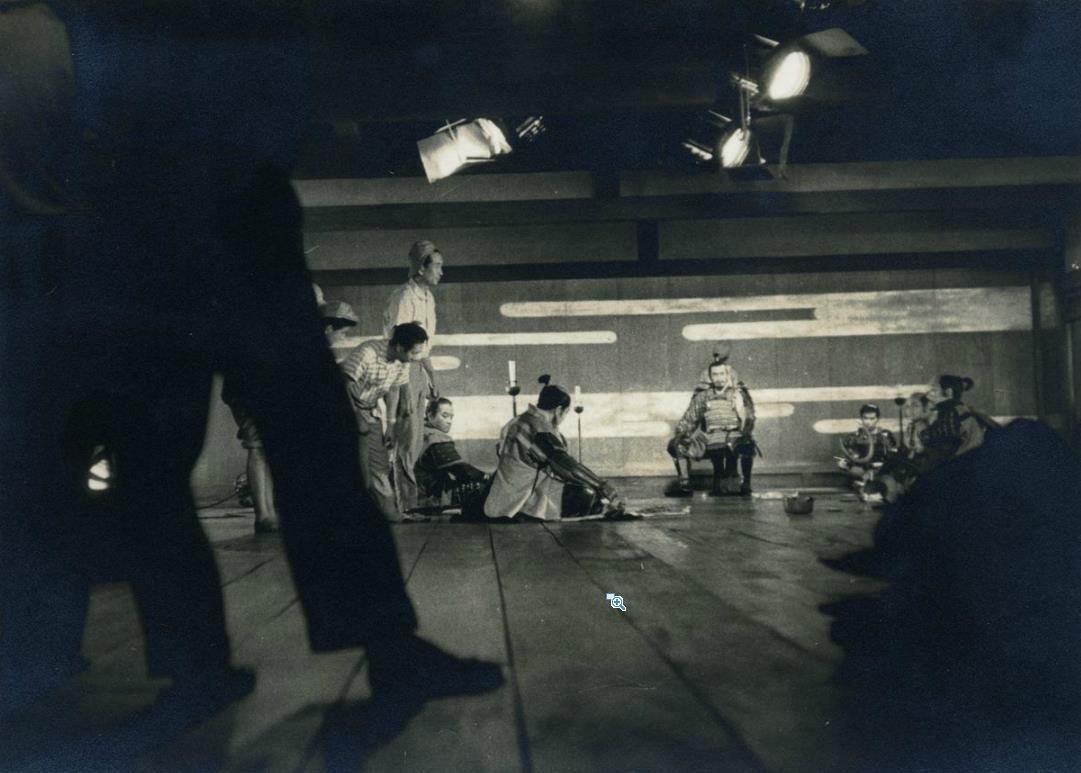

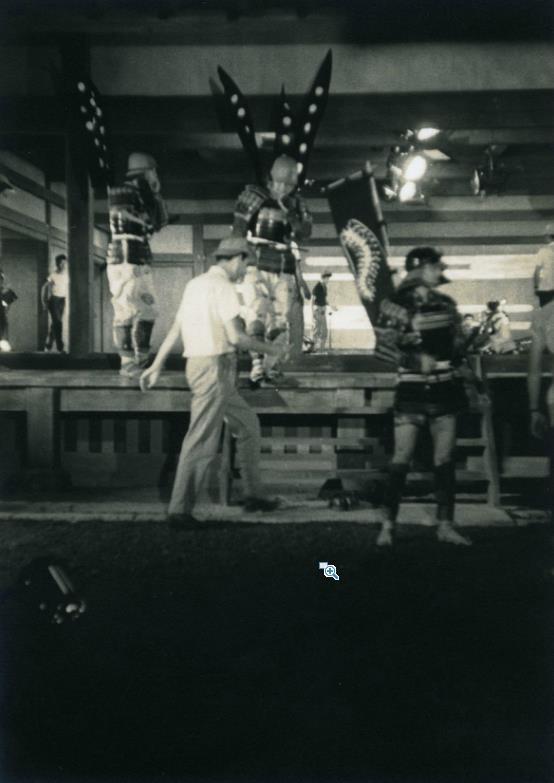

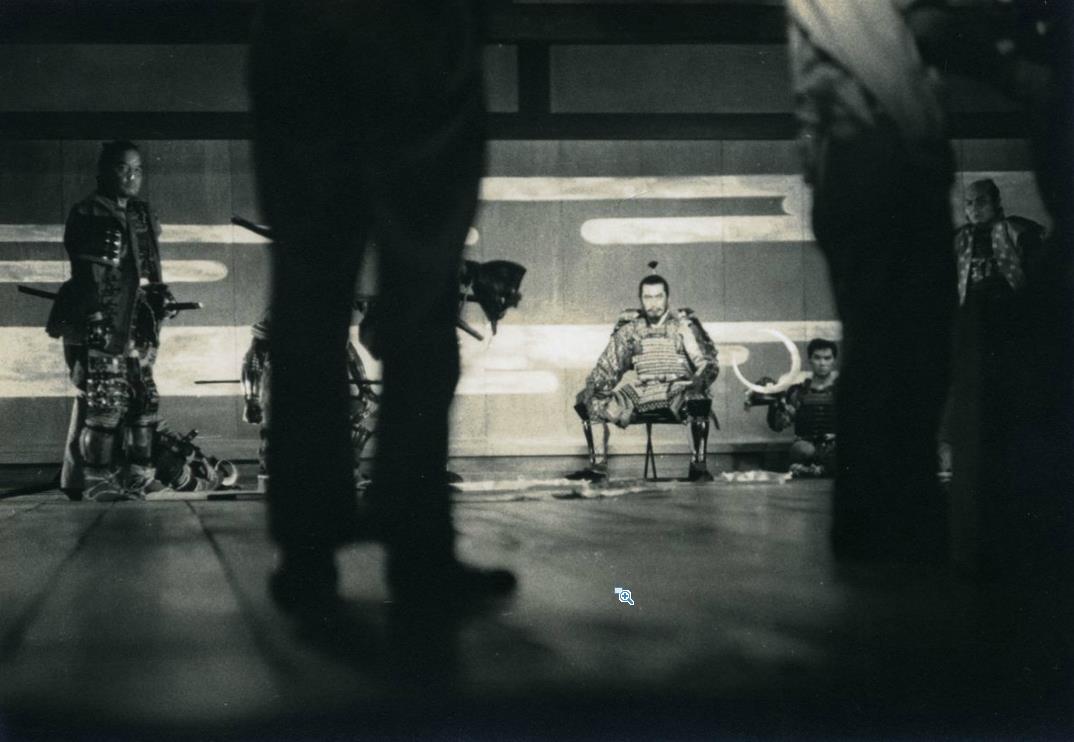

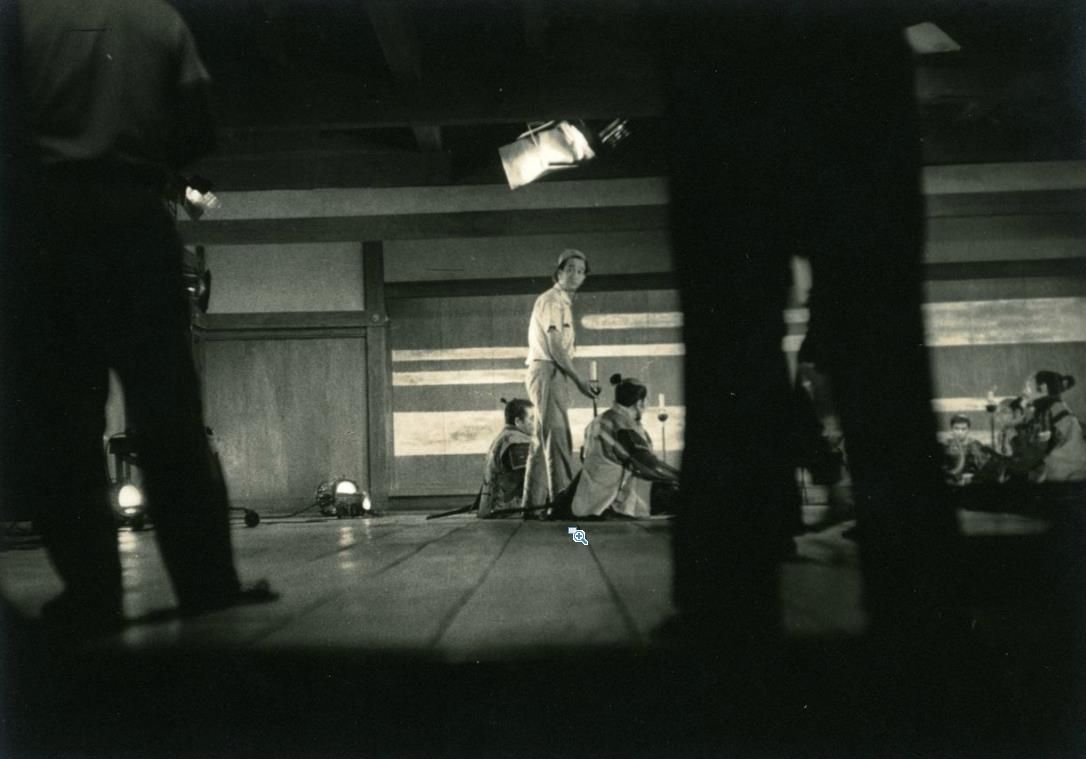

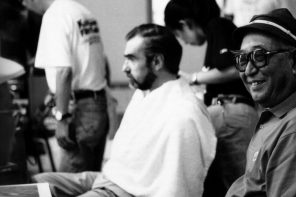

Here are several photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of Akira Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood. Production still photographer: Masao Fukuda © Toho Company, Kurosawa Production Co., Akira Kurosawa Digital Archive. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

We’re running out of money and patience with being underfunded. If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or donate directly below:

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in

[newsletter]