By Sven Mikulec

One of the very few filmmakers we deeply cherish above almost all others and whose work we hold in the greatest esteem is Jean-Pierre Melville, the highly influential French filmmaker who reached his peak in the sixties, and succumbed to a heart attack at the age of only fifty-five. Even though intense gangster films probably first come to mind when one considers Melville’s career, the truth is he showed a wide range and diverse interests throughout his filmmaking life. Being of Alsatian Jewish descent, Jean-Pierre Grumbach had to flee Nazi-occupied France and, having joined the French Resistance, took the pseudonym Melville, to honor the American novelist dear to him. Once the war finished, Melville kept his new name and went on to make movies, many of which visibly affected by his war-time experiences. The sheer scope of the influence that his work still wields over filmmakers around the globe is unbelievable, as he not only captured the attention and imagination of millions of filmlovers, but also stimulated filmmakers, swayed them into perfecting their craft.

John Woo, for instance, said Melville was God to him, praising the French filmmaker’s fresh, unprecedented approach to old American gangster films they both admired. Melville, Woo continues, approached this subject intelligently and like a gentleman, with lots of self-control, which enabled him to make movies that seemed cold and distanced, but are bound to make an emotional impact on the viewer. We use Woo’s words because they describe Melville’s technique perfectly. Le Samourai remains one of his most famous works—and with very, very good reason—but who can forget some of the other masterpieces, the breathtaking and uncompromising efforts such as Army of Shadows, Le deuxième soufflé or Bob le flambeur? Had Melville’s health been a better friend to him, we would have probably had the chance to enjoy far more splendid films from his workshop. Betrayed by his heart practically at his professional prime, Melville still made an immeasurable impact on the world of film, for which this filmmaking poet will forever have our neverending admiration and most profound gratitude.

In 2008, the first feature documentary about this great artist saw the light of day. Code Name Melville, directed by Olivier Bohler, offers seventy-six minutes dedicated to illuminating Melville’s time in the French Resistance and the influence it had on his work. First shown in Taiwan, followed by French and Belgian television in 2010, Code Name Melville gives us precious insight into the life of a true artist and one of cinema’s greatest. This film is also available as extra material on the European Blu-ray Le Cercle Rouge produced by Studio Canal Collection, as well as Blu-ray/DVD Le silence de la mer from the Criterion Collection. Our highest recommendation is to acquire this as soon as possible!

The following article originally appeared on Edwin Adrian Nieves’ A-BitterSweet-Life.

(In 1996, the French journal Cahiers du cinéma dedicated its November issue to director Jean-Pierre Melville. Included in the special edition was a version of this tribute essay by director John Woo, which was dictated to Nicolas Saada in English.)

In Melville’s films, like in mine, characters are caught between good and evil; and sometimes, even the worst gangsters can behave in the noblest fashion…

Melville is God to me.

Le Samourai was the first of his films that I saw. It was released commercially in Hong Kong in the early seventies and immediately turned Alain Delon into a major star in Asia. We had seen Delon in Rocco and His Brothers and Purple Noon, but Le Samourai made him popular among the general audience.

In fact, it changed a whole generation of filmgoers. Before that movie, younger audiences in Hong Kong just enjoyed Cliff Richard, Elvis Presley, and the martial arts films; life seemed simple and easy. When Le Samourai was released, however, it was such a huge hit among the young that their whole lifestyle began to change. The film had an impact on fashion, too. Take myself, for instance: I was almost a hippie, wearing long hair… Right after I saw Le Samourai, I decided to cut my hair like Delon and started wearing white shirts and black ties.

Le Samourai was also our introduction to Jean-Pierre Melville. When I first saw the film, it was a shock to me: Melville’s technique and his cool narrative style were incredibly fresh. I felt like I was watching a gangster film made by a gentleman. I was already working in the Hong Kong film industry at the time. I had been shooting experimental films, but I was primarily an assistant director to Chang Cheh. French cinema had already made a strong impression on my generation, especially the new wave films of Truffaut, Godard, Chabrol, and Demy. Before Le Samourai’s release, we could see these French films only through the art house circuit. I remember Jacques Demy’s Umbrellas of Cherbourg, René Clément’s Purple Noon, and Jules and Jim by Truffaut…

Then came Melvillle.

What Melville and I have in common is a love for old American gangster films. Although Melville was basically doing gangster films, the big difference between his work and the American films of that period was in his almost intellectual approach to the genre. Although they’re shot in a very cold way, Melville’s films always make us react emotionally. Melville is very self-controlled when he tells a story, and I find this fascinating. In my films, when I want to convey an emotion, I always use a lot of shots, extreme close-ups sometimes combined with dollies. On the contrary, Melville shoots in an almost static way, letting the actors deliver their performance, and thus allowing the audience to fully experience what is going on in each scene. As a result, his films are both psychologically and intellectually extremely involving.

I love how Melville managed to combine his own culture with Eastern philosophy. And that’s why the Hong Kong audience was so responsive to his movies. Melville often used Eastern proverbs in the opening titles of his films. He understood Chinese philosophy even more than our own people. I think that I relate to his movies because his vision of humanity is so rooted in the Eastern tradition. His characters are not heroes; they are human beings. In the gang world, they have to stick to the rules, but they remain faithful to a code of honor that is reminiscent of ancient chivalry. In Melville’s films, there’s always a thin line between good and evil. His characters are unpredictable. You never know what they’re going to do next, but it’s always bigger than life. You cannot use any formula, any moral standards, to sum up his heroes.

Jef Costello (Delon), in Le Samourai, reminds me of a classic Chinese medieval character: he was a very famous assassin, poor and wild and ruthless, who was hired to kill the king. This assassin would do anything for his friends, and even for his foes. In this particular story, the assassin fails to murder the king, in order to save a friend, and is killed in the end, just like in Le Samourai.

I believe that this connection I have with Melville also has to do with the fact that I was influenced by existentialism in the fifties and sixties. To me, Melville’s movies are existentialist, as you find in the loneliness of the characters played by Yves Montand in Le Cercle Rouge and Alain Delon in Le Samourai. Nobody cares for them, nobody knows who they are; they are loners, doomed tragic figures, lost on their inner journey.

His other influence is, of course, Greek tragedy, which had a strong impact on my films as well. My characters, like Melville’s, are sad and lonely, almost disconnected from reality; they always die in the end. But despite his heroes’ tragic fate, I don’t think that Melville was a pessimist. Although they look cool and self-contained, his characters are passionate and care about each other. The great thing about friendship is that you can really love someone without feeling the need to let him know; you just do what you can do for him. Even if you die in loneliness, and no one knows about it, it doesn’t matter–you have done what you had to do. Melville’s characters behave like that, and I believe that he was a man who always cared for others.

Technically, I love the way Melville builds the tension before the action. I’m thinking of that scene on the bridge in Le Samourai, where Delon has a meeting with a man who is supposed to give him money, but the whole thing is a trap. They both wait on the bridge. They’re walking toward each other, and nothing really happens, but there’s this dangerous feel throughout the scene, which is terrific. Suddenly, Melville cuts to a wide shot, you hear a gunshot, and he cuts back to Alain Delon, who is already wounded. In classic genre scenes of this type, you’d usually have a different setup, with a huge gunfight at the end. Melville prefers to play this in a very subdued, almost poetic, way.

I’ve always tried to imitate Melville. Even in my first film, The Young Dragon, a kung fu piece, I tried to use Melville’s approach to characters, by injecting a sense of dark romanticism that was seldom found in the kung fu genre. After that film, I wanted to direct more films in the Melville style, but the studios kept asking me to do comedies.

It was when I got a chance to do A Better Tomorrow, in 1986, that I was really able to use Melville’s style and technique, since it fit with the film’s genre, a contemporary urban thriller. I based Chow Yun-fat’s performance, his style, his look, even the way he walked, on Delon in Le Samourai. In Hong Kong, you never saw people wearing raincoats, so it was a surprise to see Chow Yun-fat in this kind of outfit. It was all part of the Melville allusions throughout the film.

In A Better Tomorrow, there is a long scene where Chow Yun-fat goes into a restaurant to do a hit. He first conceals a gun in the corridor, then walks into the room, kills a man, and, as he leaves, uses the gun he had first planted to cover himself. The whole feeling of this scene was inspired by Le Samourai; in particular, the moment right before Delon gets killed, in the nightclub, as he attempts to “shoot” the singer, carrying a gun that actually has no bullets.

The closest films I did to Melville’s in my career are without a doubt The Killer, Hard Boiled, and Bullet in the Head. I would say that The Killer is the one that stands out as the most “Melvillian.” I of course used a whole segment from Le Samourai in the opening sequence: it was inspired by the scene where Delon arrives in the nightclub and looks at the singer while entering the room.

In 1988-89, during the promotion of The Killer, I remember talking to the press and saying that the film was a tribute to Melville, and I was shocked to find that almost nobody had heard about him or Le Samourai. To my great surprise, the young generation did not know about him.

Now, Melville is the new big thing, maybe because people like Quentin Tarantino and me often talk about him. Whenever I am at a film festival, I always mention Melville’s name, and I guess that has aroused some interest in him. When I toured the United States with The Killer, I was amazed to see that the American film buffs knew so much about Melville.

Whoever watches Melville’s movies will realize how different he is from American filmmakers. He was a very spiritual director, with a unique vision.

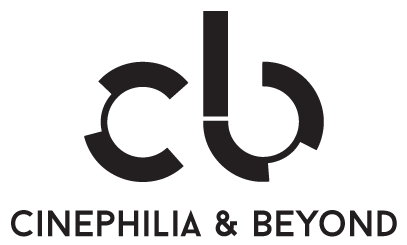

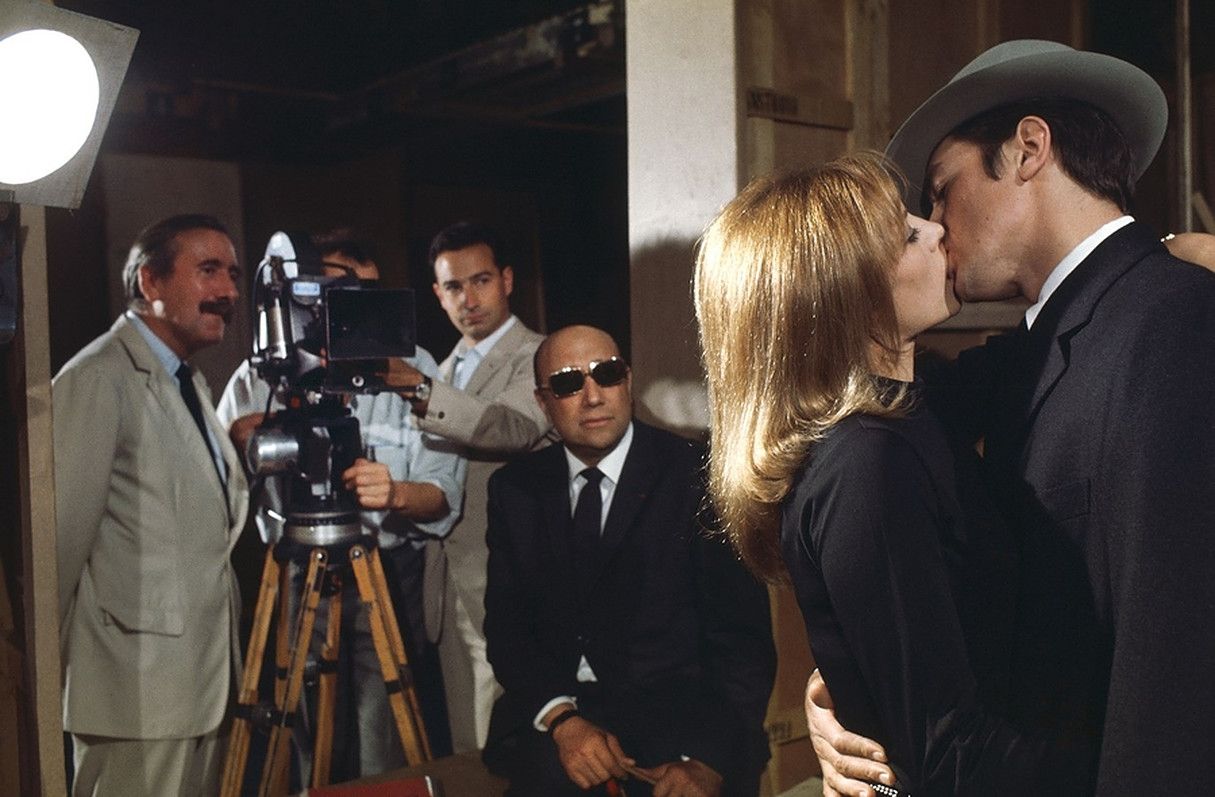

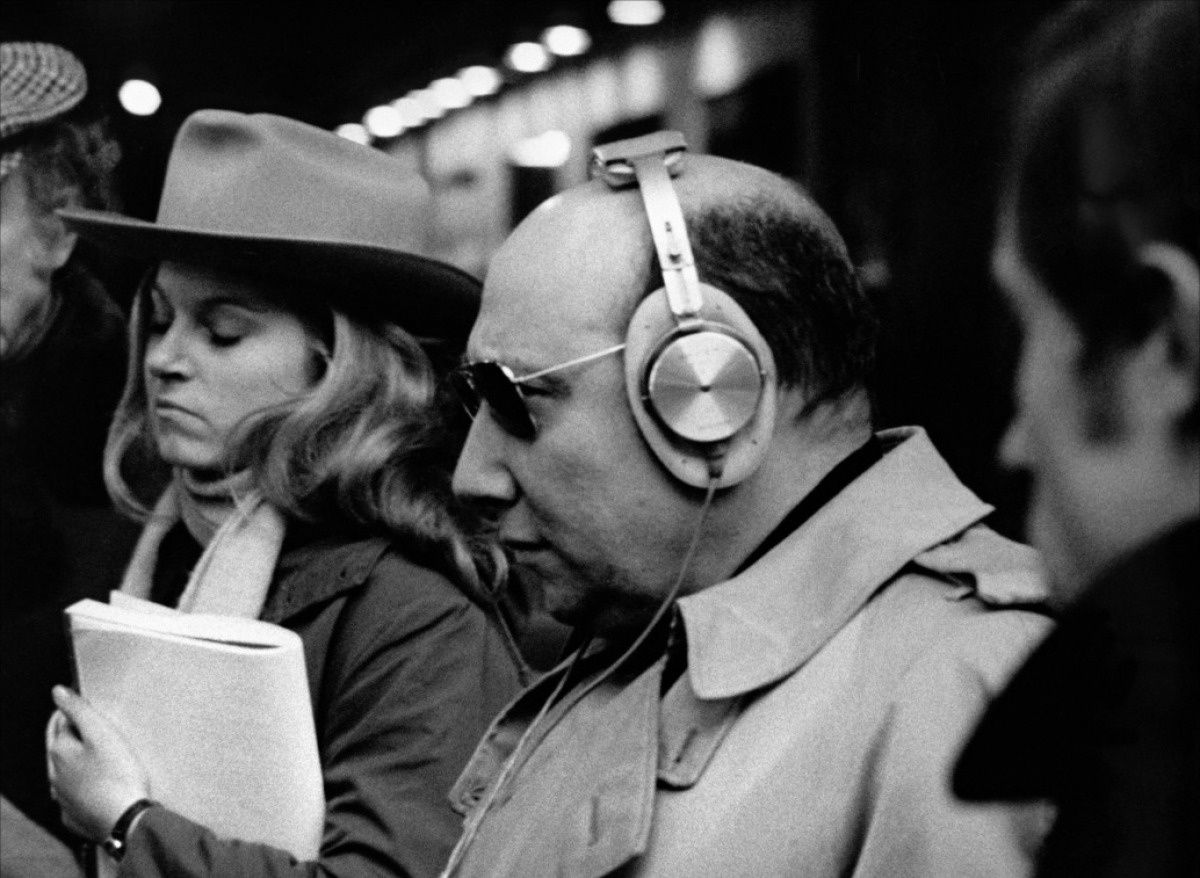

Footage and interviews with Alain Delon and Jean-Pierre Melville on the gangster masterpiece Le Samourai. Take a glimpse at Delon describe the craftsmanship of Melville. Watch, listen, and absorb the great Melville explain his beginnings as a filmmaker, his love for cinema, and his thoughts and process on the art of cinema. Courtesy of A-BitterSweet-Life.

All you screenwriters (and Melville fans) will love this. Mystery Man on Film transcribed from the Bob le Flambeur DVD parts of a 1961 radio interview with Melville by Gideon Bachmann during the Venice Film Festival as part of a radio show. Melville talks about how tough writing is for him.

JPM: It’s more difficult to write. I’m quite sure it’s easier to make a film to explain something, but it’s very difficult to write a good story, to be a man like Faulkner or Hemingway. It’s very difficult.

GB: Well, many people would contradict you and say that it’s much easier to be alone in a room with a piece of paper and a pencil than it is to be in a studio with thousands of people and lights and so on.

JPM: No, that’s not right. No. It’s very difficult to write.

GB: Do you think it’s a matter of self discipline?

JPM: Yes, and when you read many years later what you wrote many years before you become aware that it’s very bad.

GB: But that can happen with films, too.

JPM: Of course.

GB: Do you think you are less likely to make mistakes in cinema than you are in writing? Is it easier to do a wrong thing that you would not like to see in films? It seems to be much easier to make a mistake in film because it’s such a tremendous apparatus, whereas in writing you cross off a line, change a label, or put out another edition. It’s easier.

JPM: The perfection of the form is easier to grasp on film rather than in written words.

GB: That’s very interesting. I wonder why that is. Do you think it has anything to do with the way people react to the various mediums? Do you think people are more critical for writing than for films?

JPM: I tried two things—to write and to make films. Films is easier.

GB: You mean this is an empiric decision? You found this based on your own personal experience, not an abstract theory.

JPM: Yes. Subjective.

GB: I think that answers my question about why you make films. Simply because you find it easier.

JPM: I need to express something. I, of course, tried when I was young to write and I found it impossible.

The Cinéastes de notre temps presentation on Melville entitled A Portrait in 9 Poses is an essential watch for film lovers and filmmakers.

“You really create a film in the editing room, in the silence and night… For me paradise consists in writing the script all alone at home and then in editing it. But I hate the shoot. All this time wasted in useless talk!”

“I believe you must be madly in love with cinema to create films. You also need a huge cinematic baggage.”

Jean-Pierre Melville

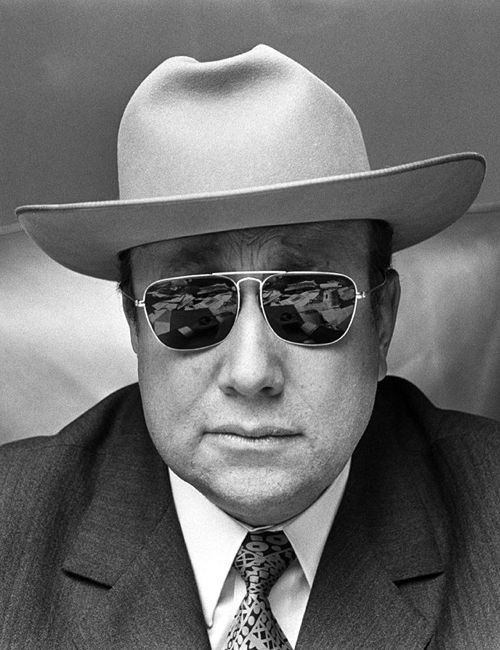

October 20, 1917 — August 2, 1973

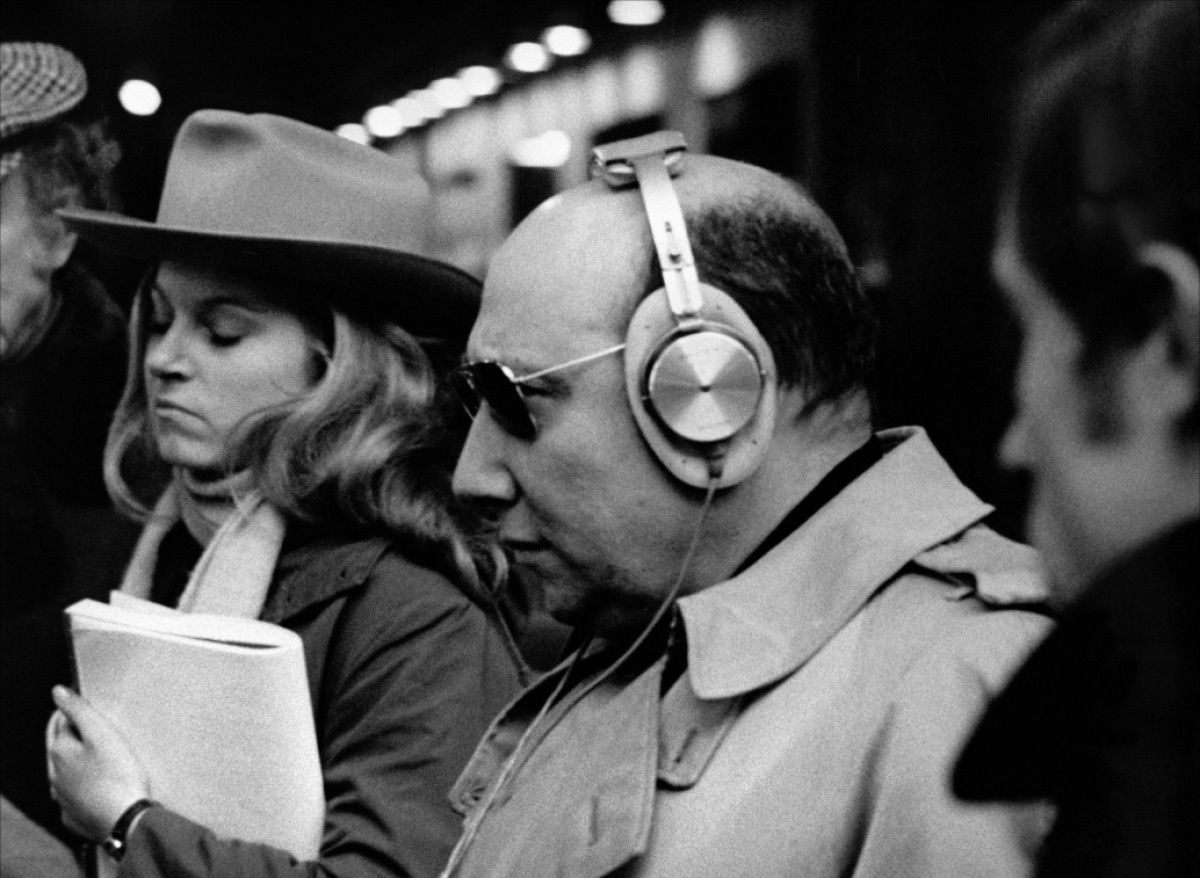

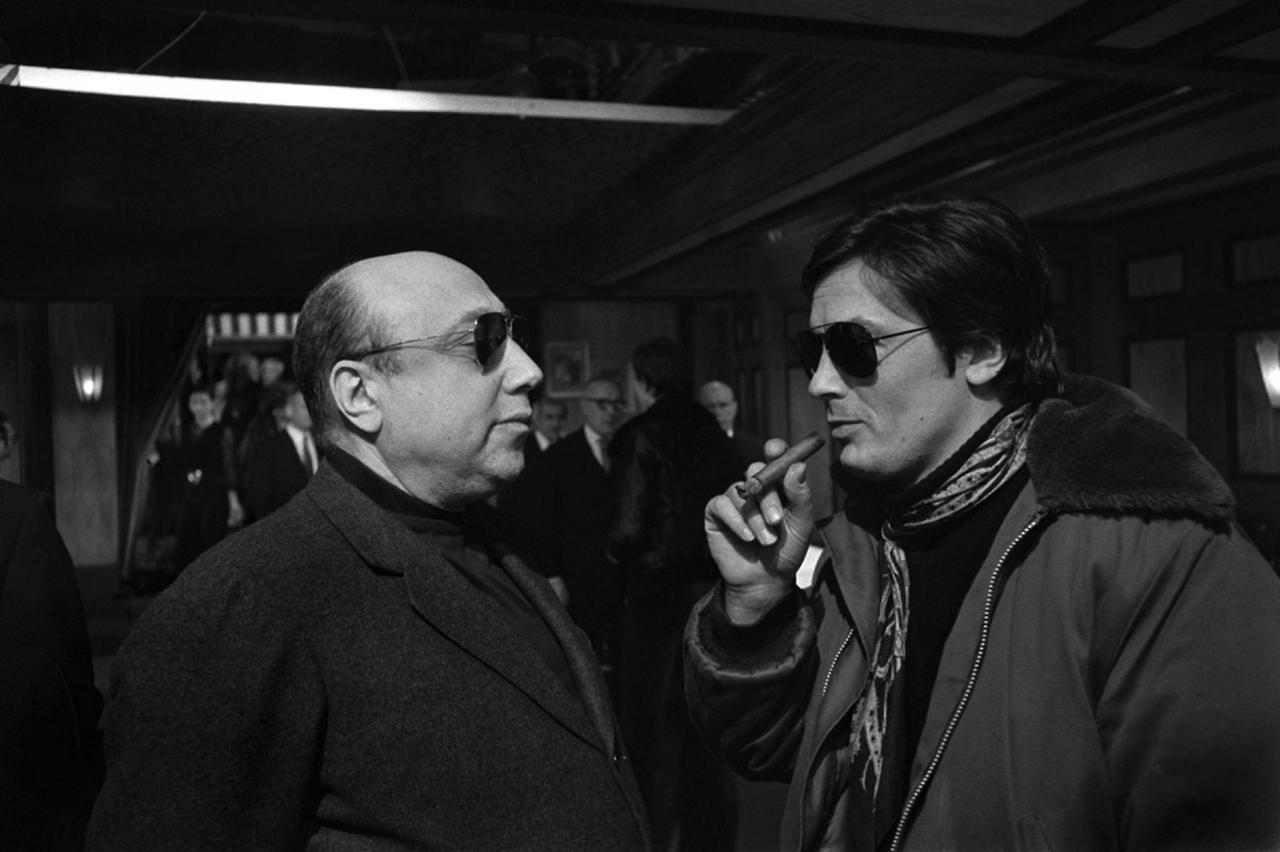

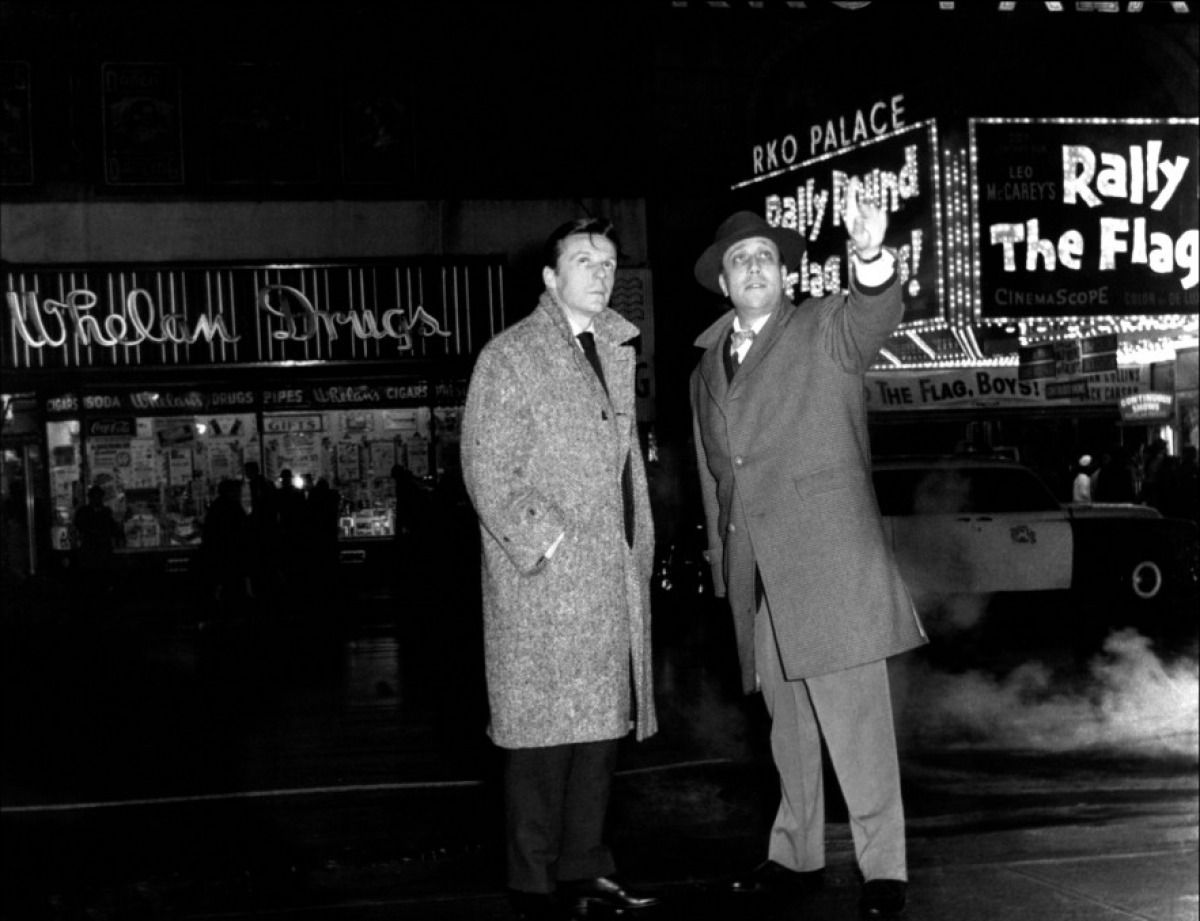

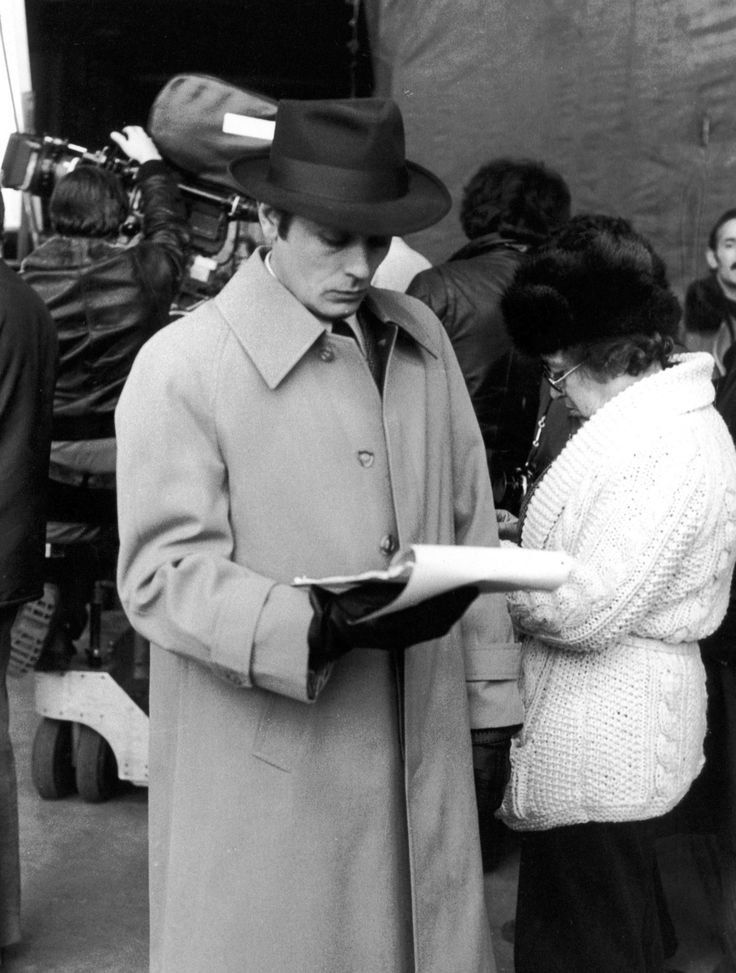

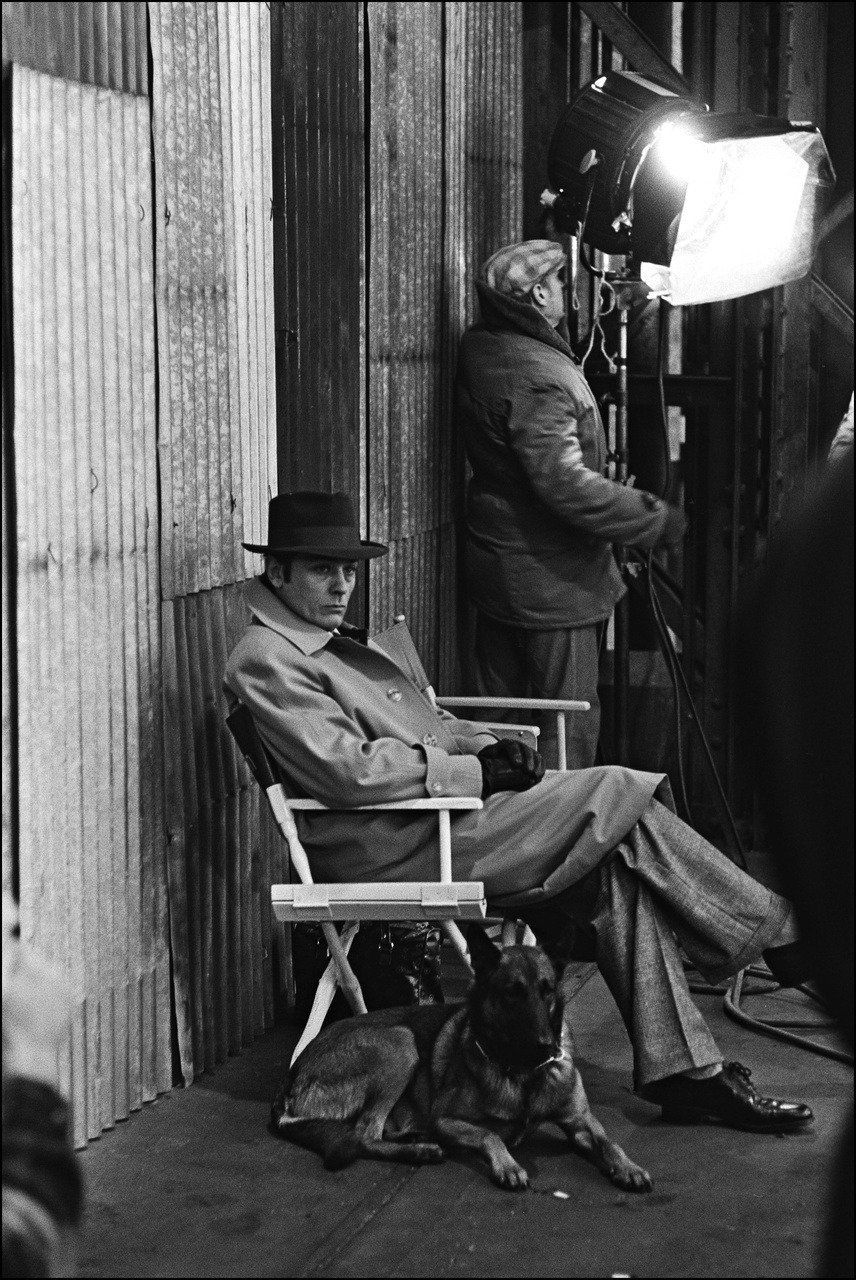

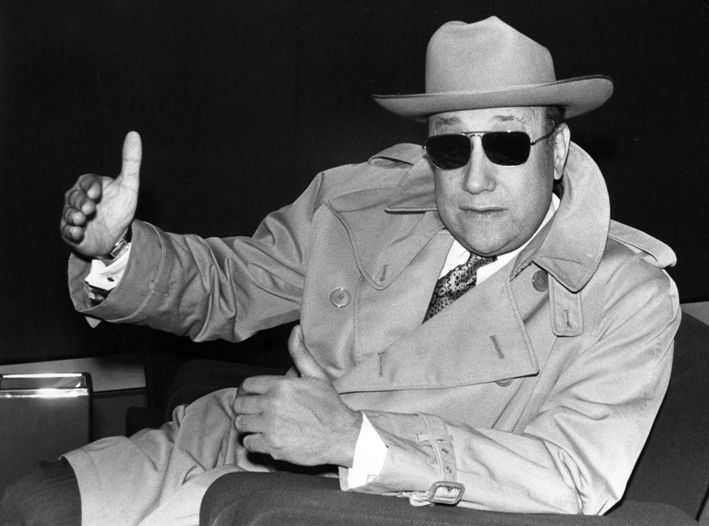

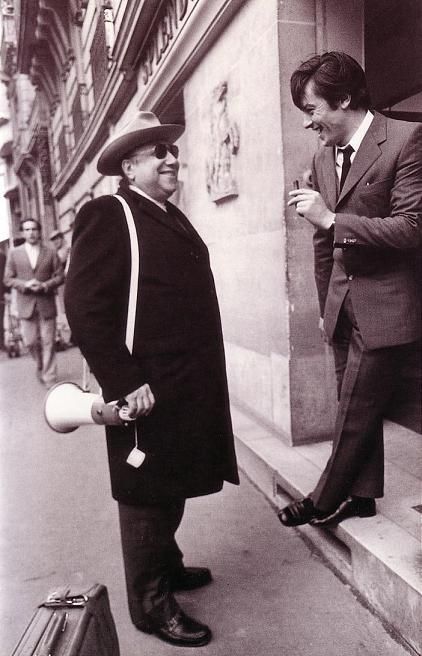

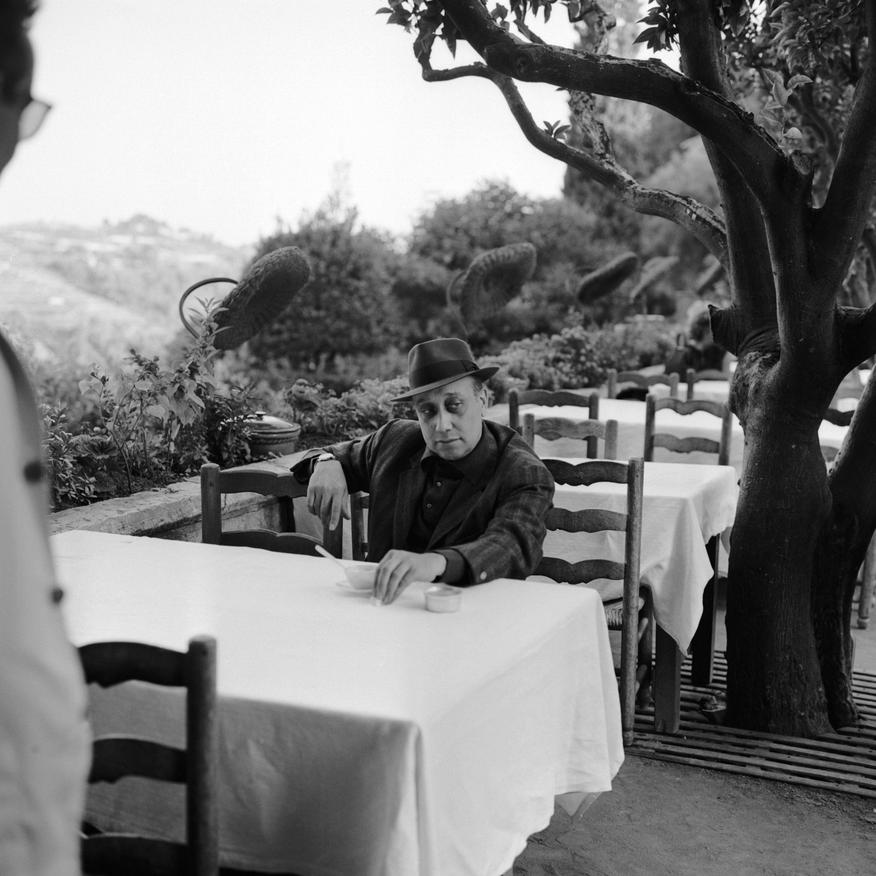

Photo Credits: Bernard Allemane / INA; Philippe Bataillon / INA; Jean Pierre Loth / INA; Aimé Dartus / INA; & André Perlstein. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or donate directly below: