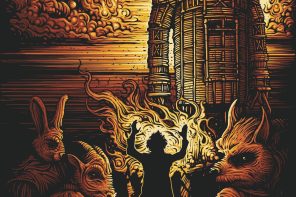

Artwork for Carlotta Films’ Ultra Collector’s Edition Blu-Ray of The Passenger by Robert Sammelin

By Tim Pelan

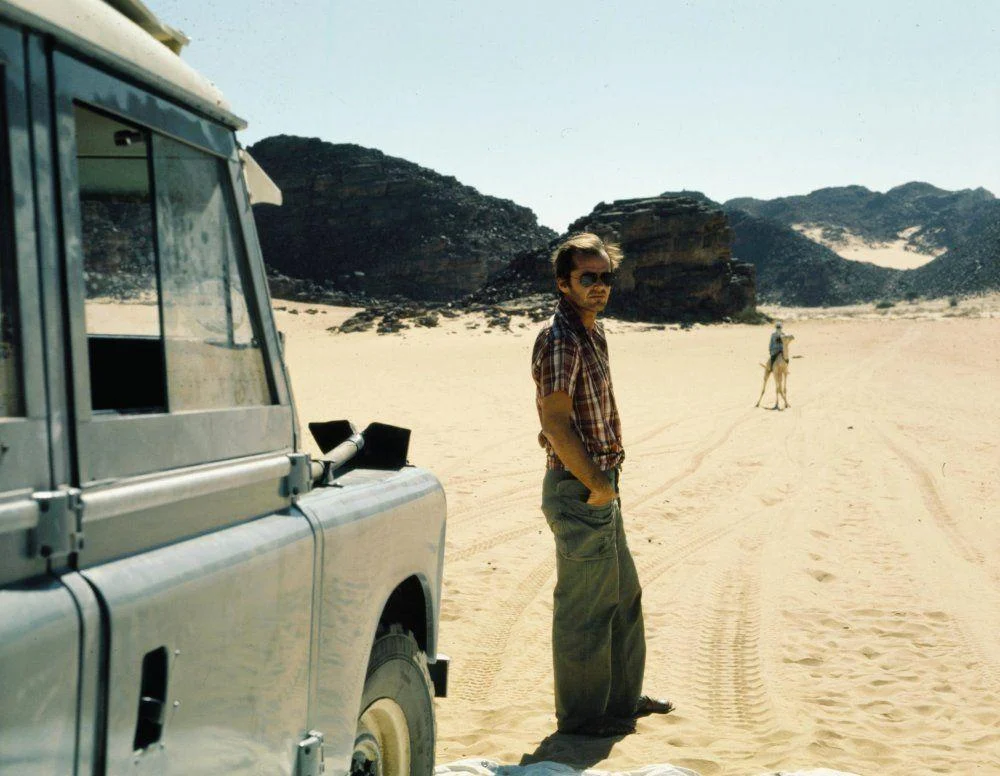

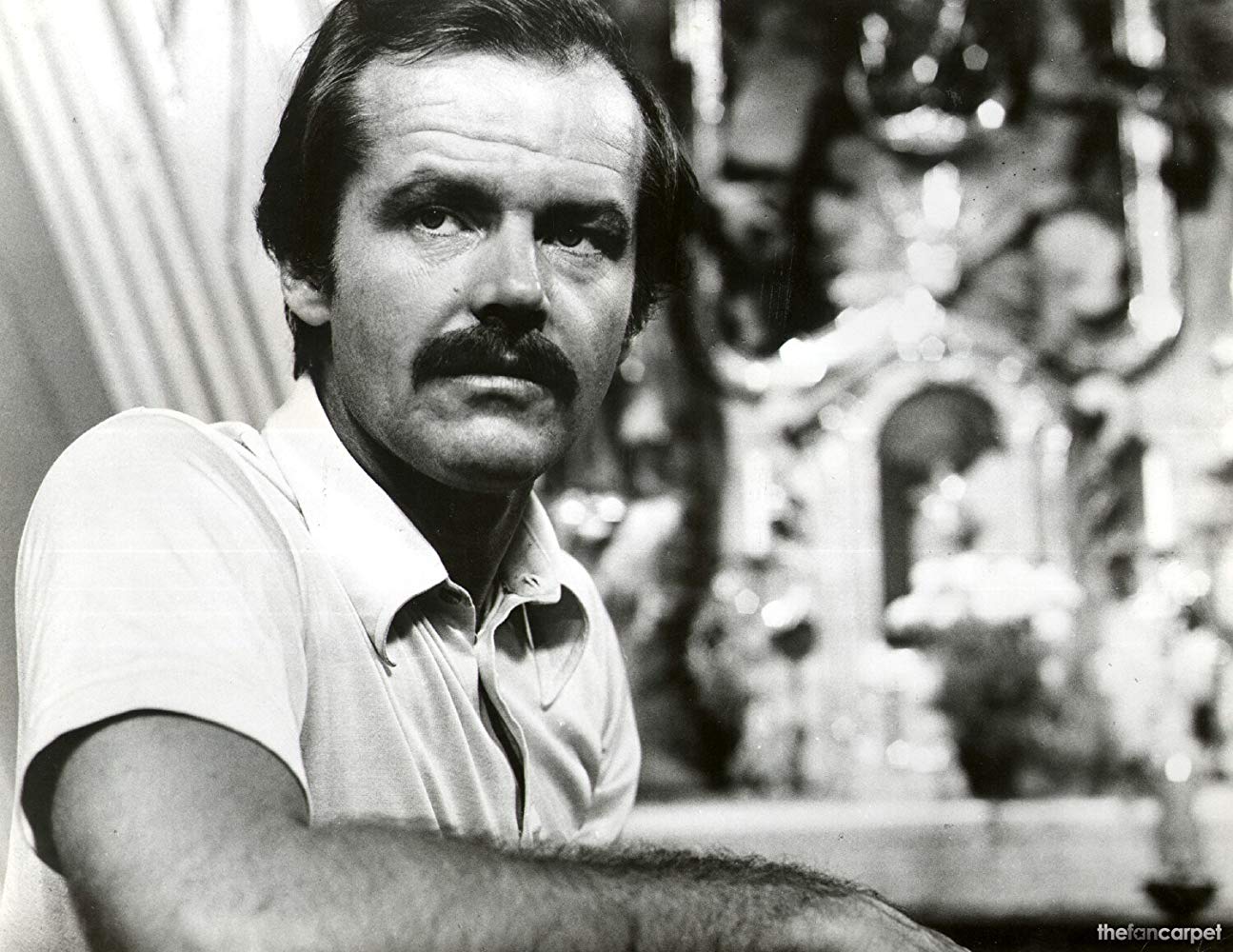

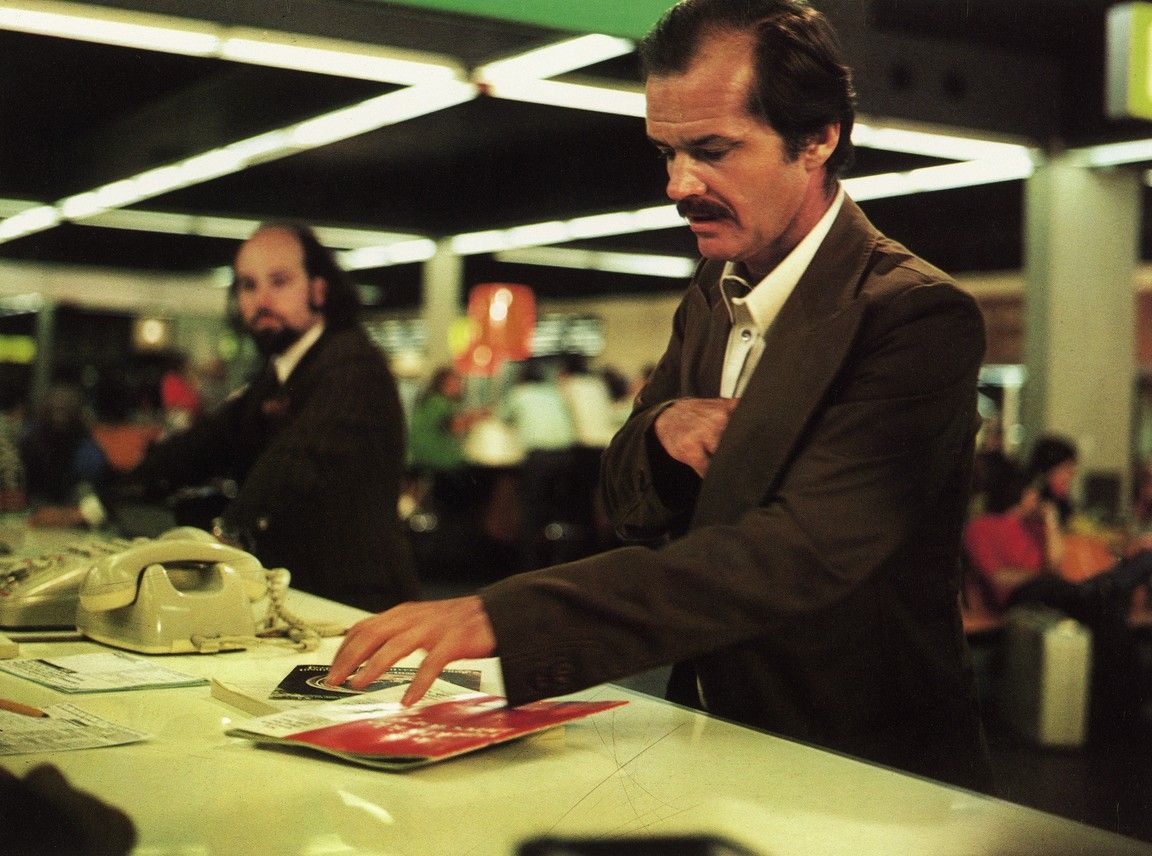

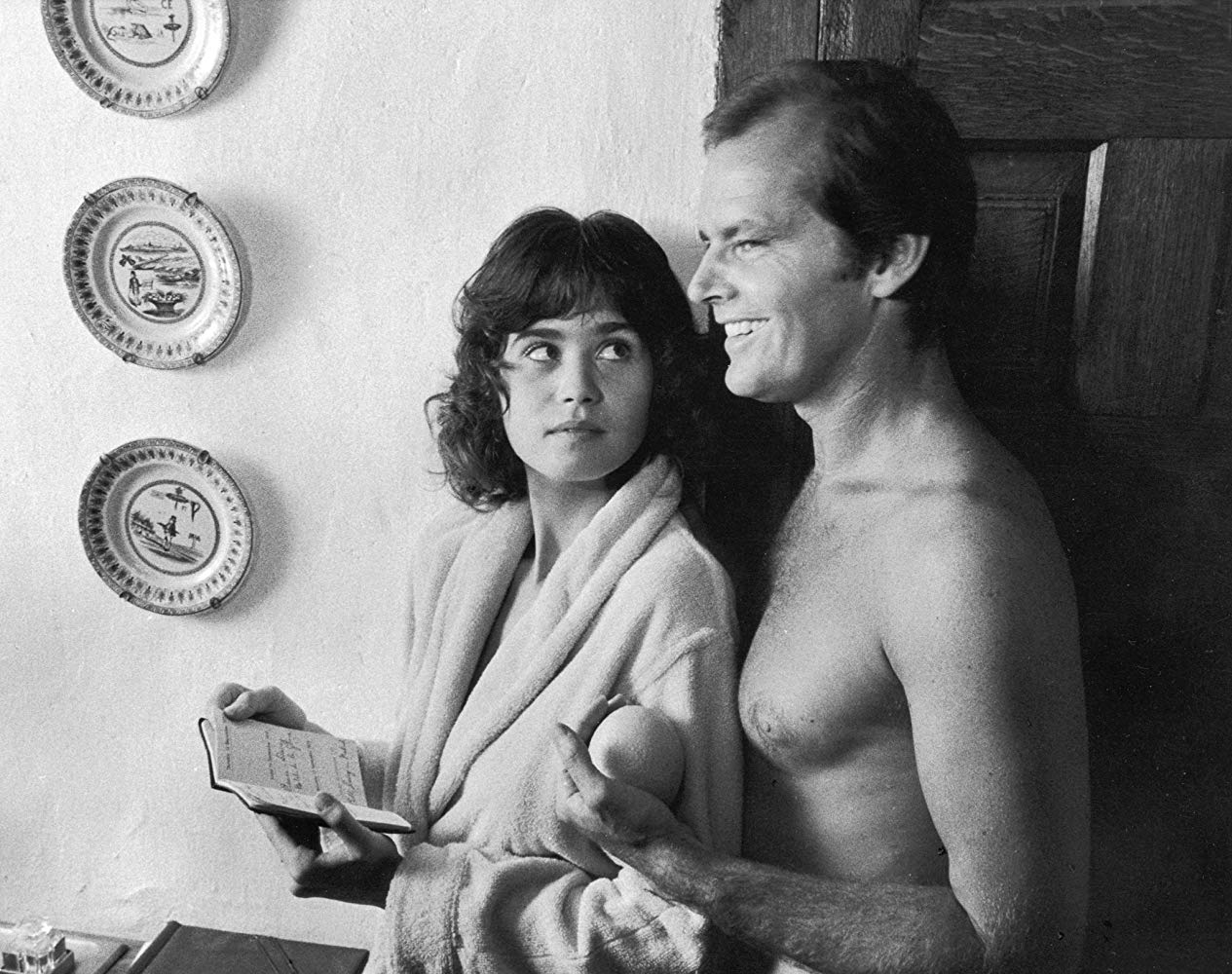

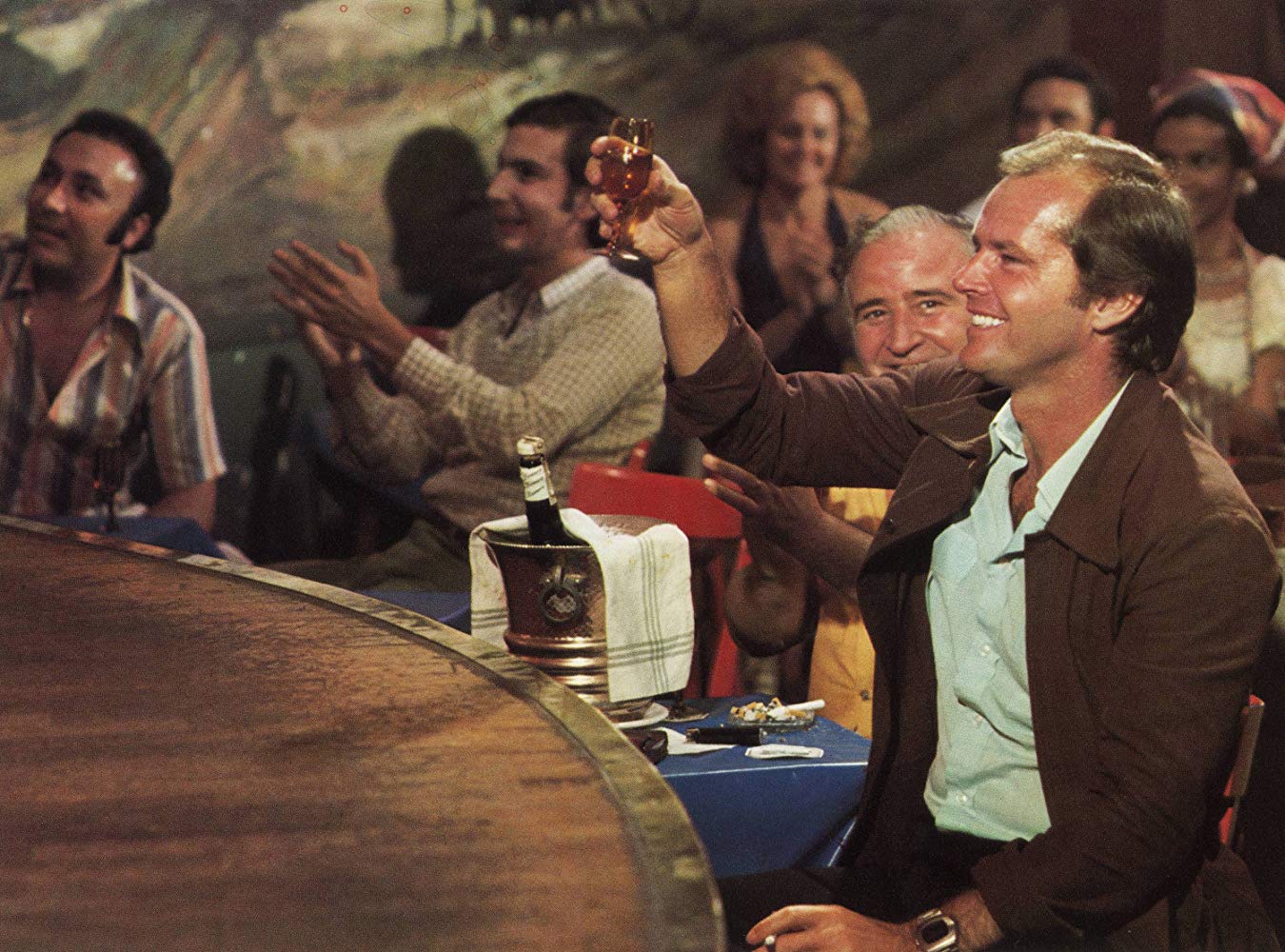

Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1975 film The Passenger is a languid thriller in which not much seems to happen, beautifully. The protagonist, David Locke (Jack Nicholson), a weary journalist chasing rebels in Chad, on a seeming whim swaps identities with a similar looking fellow traveler Robertson (Chuck Mulvehill) he finds dead from a heart attack in their dusty hotel, after their previous evening’s drinking. Locke seeks to leave his old life behind (“I’ve run out of everything… Everything except a few bad habits I couldn’t get rid of.”), following a bread crumb trail of appointments in the other man’s diary across Europe, picking up a fellow passenger, “The Girl” (Maria Schneider) along the way. He realizes the other man was an arms dealer for the rebels, and is expected to deliver weapons, for which he receives a handsome down payment. Surprisingly, he continues his odyssey, whilst Government agents, his “widow” and producer attempt to track down his alter-ego to ascertain either what he knows about the rebels and their suppliers, or about the “death” of Locke. This is a film where the language of cinema itself plays out the drama of the human mind, in which architecture and the daring use of cross-cutting from present to past tense in the same scene, can both illuminate and explore time, memory, identity, and the sense of freedom and entrapment that surround our passengers. “There are people who find this a very pretentious, implausible existential thriller,” wrote critic David Thomson. “I think it is one of the greatest films ever made… a thriller, a mystery, and a sweet, faintly sinister parable on being so loose or free to let the vehicle of narrative, or of film running through the projector, carry you away.” As I said in my piece on William Friedkin’s Sorcerer, I believe it can work as a companion piece to that film: “two existential struggles—four men seeking to reclaim value in their lives, another questioning the bourgeois value in his. Four lost in hell, the other a fallen angel in ‘Paradise.’ Each ending an ambiguous mirroring.”

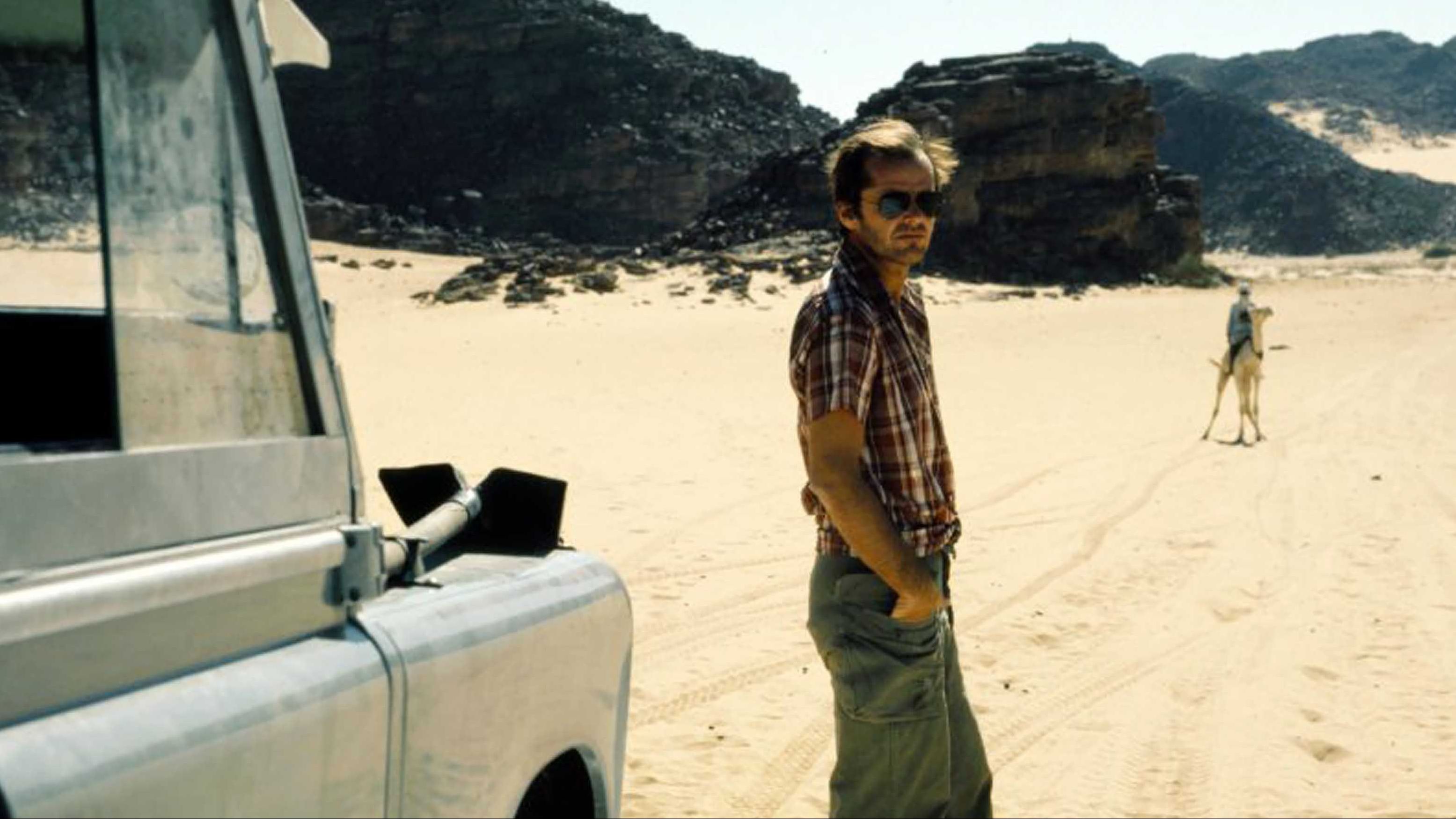

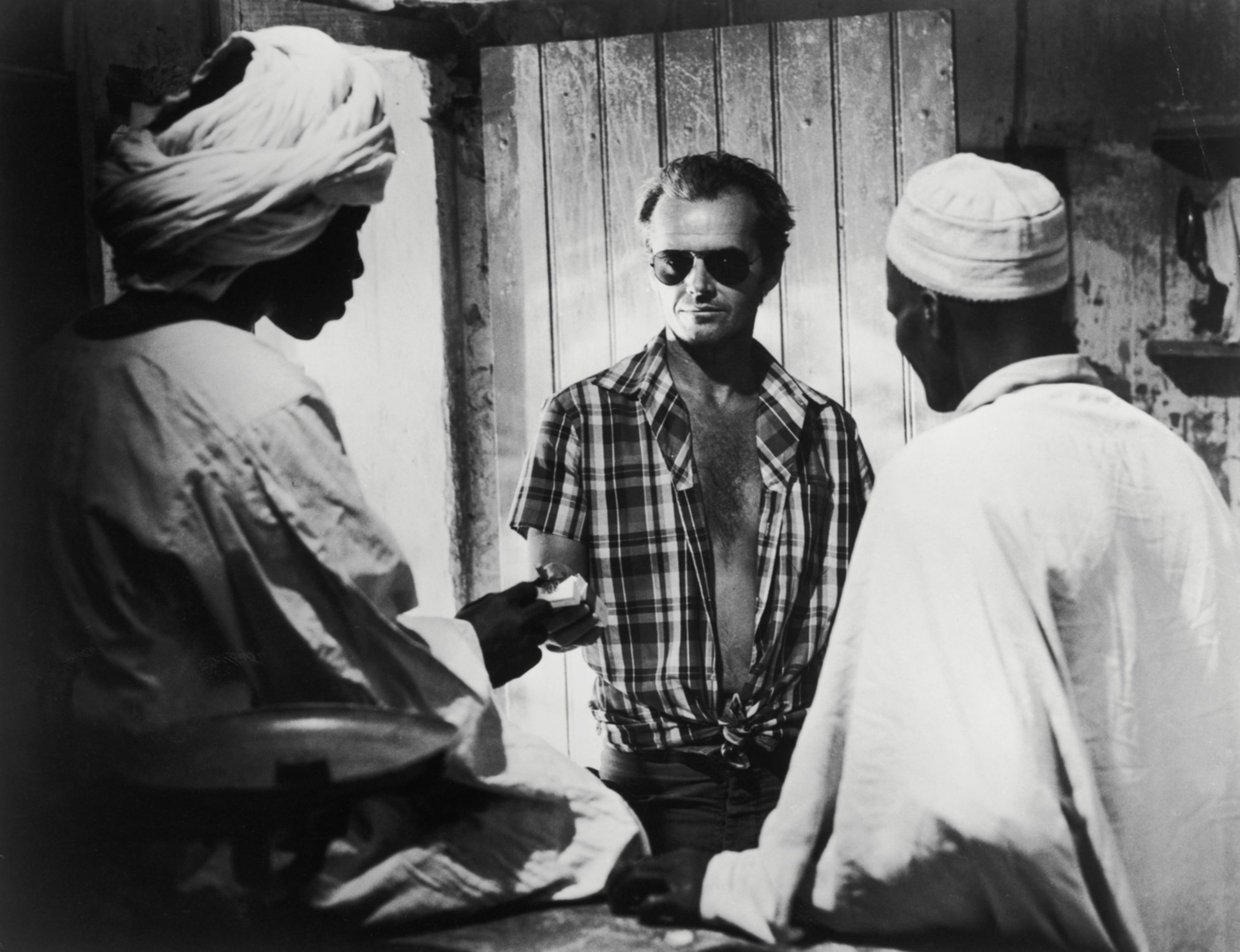

The film is from a conventional, Hitchcock-like story by Mark Peploe, reworked with him by Antonioni and Peter Wollen into a more deconstructed exercise about “fluid identity, emotional estrangement and political disengagement”—Stephen Dalton, for the BFI. The Passenger opens on a largely wordless segment in which Locke drives through various villages and on into the desert in search of the rebels, on whom he is covering a story for a TV documentary. A local guides him so far, before abandoning him when they observe a military patrol on camels. Returning in frustration to his Land Rover, it gets bogged down in the dunes and he attempts to fruitlessly extricate it with a shovel, whacking the immovable object and throwing his arms to the void, sobbing—“Alright! I don’t care!” He stumbles back on foot to his shabby hotel, demands some water, and retires to his room, before knocking next door for Robertson, finding him dead on the bed. As he examines his face close-up, a plaintive whistle plays, the fine hairs on the body’s scalp blowing in the breeze from the electric ceiling fan. It is as if a transference of spirits is playing out. Locke removes his shirt and takes Robertson’s, returning to his room and playing the tape recording of their conversation he accidentally left running the previous evening when they first met. We hear Locke say on tape, “We translate every situation, every experience into the same old codes. We just condition ourselves.” Robertson replies, “We are creatures of habits.” Locke is about to break his, and here is where some very ingenious breaking of cinematic habits also plays out.

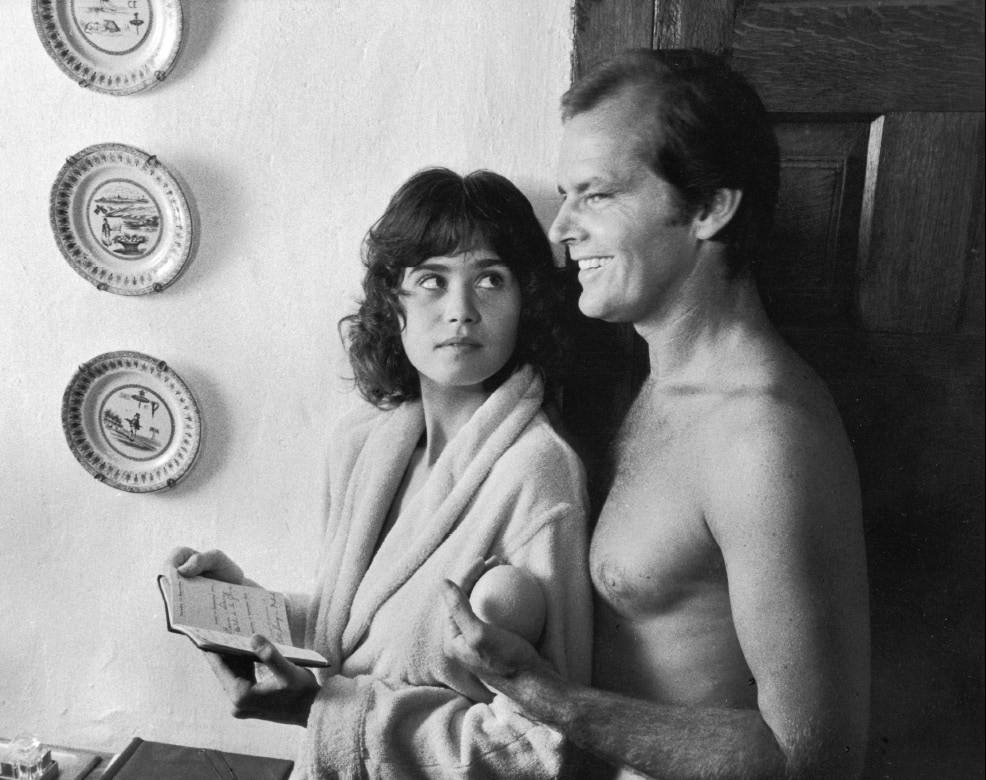

As Locke begins to carefully slice Robertson’s photograph from his passport and transpose it with his own, the previous evening’s conversation between the two men plays out, the camera panning from Locke’s running tape recorder. There follows a slow pan from Nicholson, shirtless at the task in hand, to the left and the open window, the dialogue continuing naturally, unbroken. Then suddenly a very alive Robertson enters the frame on the porch outside the window. Nicholson then steps into frame beside him, now wearing his shirt, his sweat-stained trousers replaced by an identical clean pair, continuing the conversation, observed by us through the opened window. Now “live” in a radical unbroken transition to a “flashback”, without a cut, where location and time have changed, breaking the contract between cinematic narrative norm and the viewer. Film scholar Bruce Isaacs, from his The Conversation series:

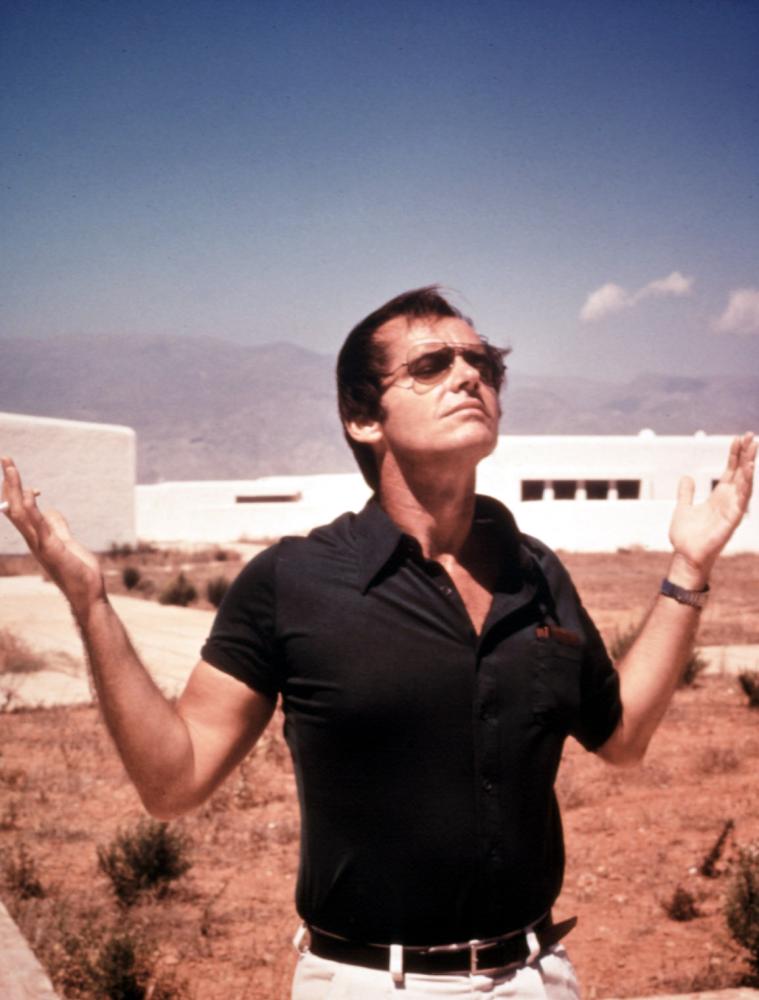

“It suggests that time is not as simple as it seems to Antonioni. And this is the philosophical concept he wants to open up. He wants to ask us, ‘How does time really work for subjects? What is subjective time versus objective time?’ Cinema tends to give us objective time, and we trust this. Antonioni wants to break that contract with the spectator… past and present conflated.” Locke is already fading into the blue walls as he dons Robertson’s blue shirt, the walls and sandy colored tiled floor a singularity of environments with the desert, wherein he abandons mankind’s attempt to control the space in which he lives. After a brief address by his real name to which Locke corrects the concierge, the fiction is maintained and continued without debate. Leah Bordenga, Interiors: “Leaving behind his camera, tape recorder, and luggage, Locke is one step closer to freedom by escaping himself. Antonioni points to the fact that modern machinery and electronics of the present cannot negate the struggles of the past (history), which are reoccurring. Man is bound by his belongings—without them, he has no identity to others or to himself, but with them, he is boxed into an identity that does not fully encompass the vastness of his true self.” From his earlier frustration with the desert to a later, temporary inner peace—in rural Spain amidst the bleached white, stark and geometric intrusions of the Hotel De La Inglesia seemingly dropped amidst the dusty, desolate flat surroundings, The Girl asks Locke whether he finds the landscape pleasing. “Yes,” he replies, “it’s very beautiful.” Following their earlier playfulness at their game he is now seemingly accepting of a world of chaos beyond his control, an entropic encroaching on his priapic self.

We will see variations of this playfulness with cinematic convention throughout the film, transitions of memory from one character to another in the same scene, and in observations on the nature of subjective and objective participation in dialogue between subject and questioner; even the use of seemingly real documentary footage to challenge debate within the viewer.

From Antonioni’s 1975 production notes:

“In this journalist (Locke) there coexists the drive to excel, to produce quality work, and the feeling that this quality is ephemeral. The feeling thus, that his work is valid for a fleeting moment only. In fact, no one can better understand such a feeling than a film director, since we are working with a material, the film stock itself, which is ephemeral as such, which is physically short-lived. Time consumes it. In my film, when Jack (Nicholson) feels saturated to the gills with this sentiment, after years of work, with age, a moment arrives when there is a break in his inner armor when he feels the need for a personal revolution.”

Back in London after news of his “death” has been relayed, Locke’s wife Rachel (Jenny Runacre) a fellow journalist, and his producer Martin Knight (Ian Hendry) go over the material of Locke’s for a tribute broadcast. There are three items of particularly telling interest. In one, he interviews the dissembling African president, wherein Locke fails to adequately challenge him about his policies and the reality of the situation in his country. As Rachel looks up at the moviola screen, she tells Knight she was there, and again, we “jump into” the past via film, Rachel now observing her husband at work off to one side. Later, as they leave the president’s home, she tells Locke, “You involve yourself in real situations, but you’ve got no real dialogue. Why didn’t you tell that man…”

“That he’s a liar? Yes, I know, but those are the rules.”

“I don’t like to see you keep them.” Did she push, or did Locke jump?

In an interview with The Guardian, Runacre ruminated on the film, and this scene. “He’s not true to his ideals. He’s lost his integrity. He’s become a void, which is why she leaves him.”

In another interview Knight pours over, Locke questions a Witch Doctor (James Campbell). Locke expresses latent colonialist surprise that he has not abandoned his supernatural ways, since he has been educated in France and Yugoslavia. “Has that changed your attitude toward certain tribal customs? Don’t they strike you as false now and wrong, perhaps, for the tribe?”

The Witch Doctor suggests, “Your questions are much more revealing about yourself than about me,” before taking the camera and turning it on Locke, no longer detached, but implicated in the story. Tellingly, he turns the camera away and refuses to play. It is Locke’s detachment, ironically lauded by Knight, that weighs him down. He has a kind of psychic breakdown in the desert and decides to abandon his identity and take on Robertson—did he really naively believe his story that he was “globetrotter”, who simply “takes life as it comes?” Discovering instead a more concrete commitment and mainline to the rebels he sought to find, through the “daisy chain” link of meetings with the mysterious “Daisy” in Robertson’s diary.

The third documentary footage item is an execution on a beach by a firing squad, seemingly real, of an event on Nigeria’s Lagos beach, spectators, the press et al invited. And by extension, we, the viewers, are complicit, invited to consider our own feelings on such deeds happening every day in the world. The camera tracks and zooms in on the bound man shot, and shot again as he slumps in his bindings. It is implied Locke has shot this dispassionate footage. Antonioni:

“This is a very ambiguous piece of film. Locke is doing a documentary film on a guerilla movement within an African country… We can think he chooses the execution because he knows that it will be visually impressive. He may have chosen it for sensationalism but perhaps not. We don’t know, and perhaps he, himself, did not know what he wanted. I begin the sequence with a full screen as though it was happening at that moment. And then we see it viewed by the television producer on the moviola for his documentary of David Locke’s life as a journalist… I recorded the execution twice so that the audience’s perception of that event would be different each time that they watched it. The format on the screen was different from the format on the moviola. It was as though I was filming the execution myself. And then it was watched by Knight and Rachel on the moviola as film shot by Locke… My intention was to show something that shocked Locke… He is, of course, a very conventional interviewer and this is what Rachel accuses him of.”

Antonioni in The Passenger sought to be free with his camera, to elide character rather than explain, inviting the audience on a journey of slow discovery and open interpretation, through a series of fragmented, drawn-out encounters and pursuits, often viewed by us as almost voyeurs. This is a mystery film where we sometimes seem as in the dark as the onlookers our characters walk through. In Barcelona, Knight has tracked down “Robertson” to his hotel, but has “just missed him.” He gathers The Girl knows him. She invites him to follow her car in a taxi and loses him at the lights, the camera remaining behind Knight’s stationary vehicle as the car pulls ahead and around the corner. In a crowded square in Munich, Government goons swoop on the rebel operatives Locke was due to meet, bundling them off to collective confusion, a frozen moment in time captured by “us” on the fringes, a water fountain partially obscuring the action. During their interrogation, the camera tentatively tracks into a broken window at the questioning going on. The captive is invited outside to the yard. There seems to be an impasse, the other agent’s body language seems to say. Then suddenly, an explosive kick and judo chop to the neck. Still we hang back, shocked by the force expressed. From a chop, to a cut. And scene.

Antonioni’s almost detached point of view and distancing is realized by the breathtaking cinematography of DoP Luciano Tovoli. Repeating motifs, focus on water and sand, gliding camera, slow pans and figures entering the frame from odd angles, often without any other sound than what is naturally occurring in the scene (the crunch of gravel, the snap of burning leaves and twigs, the hum of a rotating ceiling fan), suggest we are privy to a drama playing out in secret, which only we get to observe and imagine. Colors pop in that way that only films of this era can. The Passenger is an obvious influence on the also languidly paced BBC adaptation of John Le Carre’s The Little Drummer Girl, but I imagine its cinematography and focusing on the elements was also a stylistic influence on Marc Forster’s slightly more hectic but no less artful James Bond adventure, Quantum of Solace. Daniel Craig’s Bond also takes the place of a dead body in a backwater hotel room (although he did kill the guy himself!). Bond girl Camille even slightly resembles Maria Schneider’s character. And her words “I wish I could release you, but your prison (she strokes Bond’s temple) is up here,” almost reflect The Girl’s attempts to lift Locke’s spirit.

From that Interiors piece again: “Antonioni frequently uses bars or birdcages—literal and metaphorical—emanating the restrictions of mankind that modernity tends to mask: history repeating itself, unable to break out of natural or cultural boundaries, or even how the physical architecture of buildings and streets create social habits limiting us to the space we can use. In a scene where Locke rides in a cable car over the port of Barcelona, he emerges his upper body out of the window. In the next frame, he is entirely surrounded by blue water. He flaps his arms like wings, feeling the unbounded freshness of his ‘new self’ if only for a moment. The next shot cuts to a low angle inside the Umbraculo located in Parc de la Ciutadella; we are deceived by the tall, vibrant, green palm trees and natural light which are entrapped under a roof.” It is here where Locke, waiting for a contact that never arrives, chats to an old man. As the old man begins the tale of his life, “One day, very far from here…”, sound and image fade, replaced by the beach execution discussed earlier—as if in flashback.

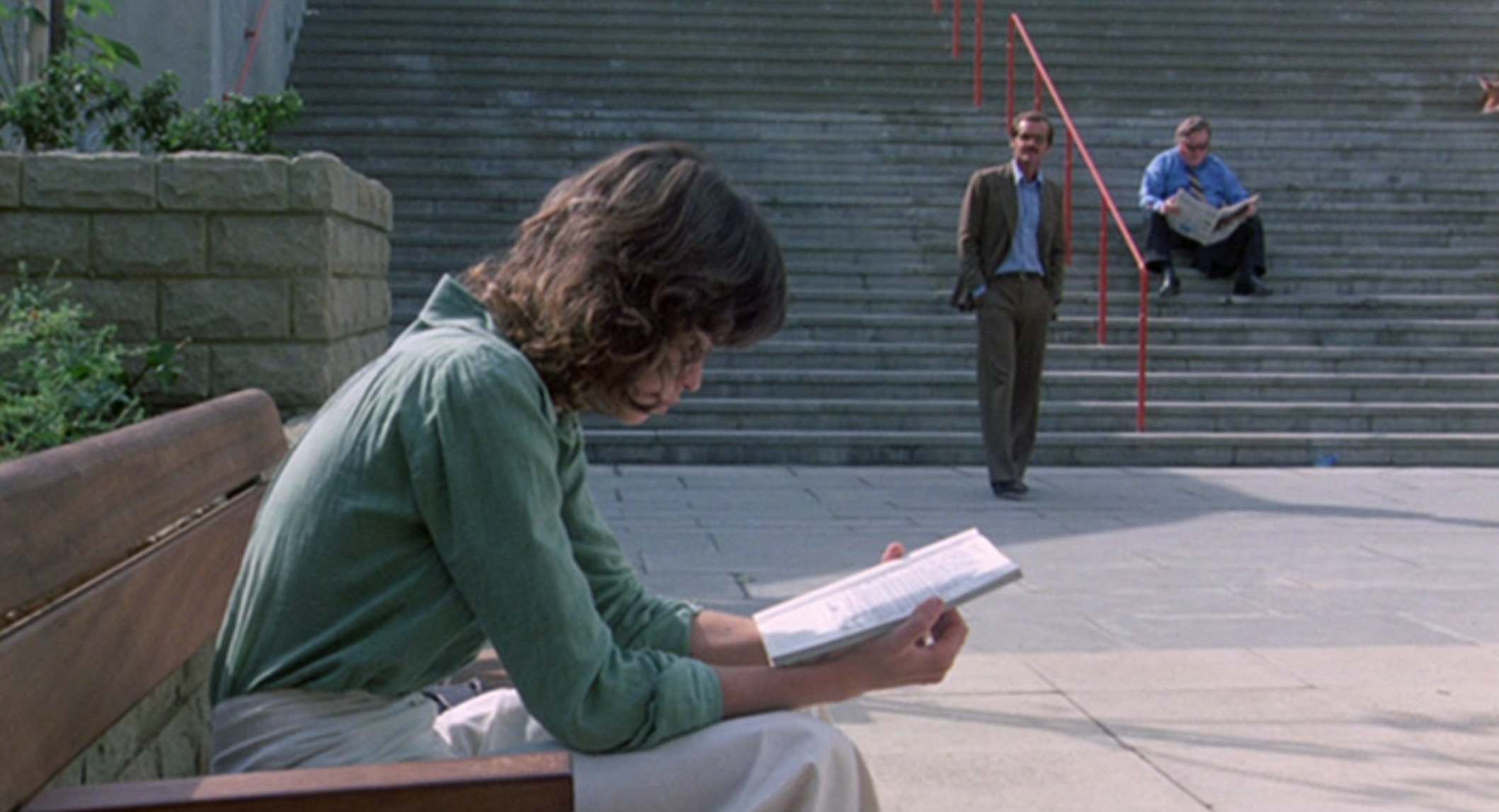

He often uses repetition and callbacks throughout the film. Early in his new life in London Locke briefly stops to admire a young woman, leaning back on a bench, arms outstretched, soaking up the sun like a cat, foreshadowing his bird-like arm flapping from the cable car. This is The Girl he meets later in Barcelona, a young French architecture student who decides to abandon her own travel plans and accompany him on his adventure (for at this stage at least, it is still an adventure, not a purgatorial pilgrimage). They meet in Gaudi’s famous Palau Guell. The interior is dark stone and wood (cool, for the summer heat)—“The interior is an imprisonment of self: the dim light peaking through the slotted lateral windows gives little solace and instead of bringing in the outside world, only demonstrates to Locke how far removed one is from it, thus forcing him to exit the building in haste.” (Interiors again.)

Locke is stifled, he can’t breathe. They exit to the roof, where wide shots of textured, curved sculpted form seem to merge with nature, reflecting back an African influence on the architect. The Girl’s flowing long skirt, sandals and loose blue shirt suggest a communion with the elements up here. Locke is lost in the dunes again, adrift, but breathing, unfettered. The city is too overpowering—they leave in an open-top convertible. She asks “one question”—what is he running from? He grins and tells her to turn around, and she spreads her arms again, joyfully observing the tree-lined road recede to a single point behind them, the wind whipping through her hair. These happy moments will also recede into the past as the inevitability of fate snaps at Locke’s heels.

Rachel is now in Spain, having been forwarded her husband’s belongings and naturally surprised to find a stranger’s face in his passport. Locke narrowly avoids her in one hotel foyer, in a sort of callback to the earlier hotel tape recorded out of frame sound. Rachel is talking on the phone in a booth in the foyer. Locke is at the reception desk. Rachel’s voice cuts into the frame as if from his past that he is running from, the camera pans again. As he bolts to the car she catches a half-realized glimpse of him and also rushes out, but he is gone, for now.

With the police now on his tail, Locke believes it would be safer for The Girl to go ahead and meet him in Tangier. He goes ahead to the next meeting place, the Hotel de La Gloria. He is surprised to find “Mrs. Robertson” is already booked in, and they are given adjoining rooms. It’s The Girl. What compels her to hang around? Some theories speculate she is the mysterious “Daisy”, or Robertson’s estranged wife, but it doesn’t really matter. Locke, flagging, tells her a story about a man he once knew, blind until the age of forty, who regained his sight. At first it was wonderful, a miracle, so many delights and wonders. But later, he told Locke, no-one ever told him how dirty the world was. Depressed, he took his own life. Locke then asks The Girl what she sees outside the room, and she recounts the everyday sights in the square between the window and the bullring—“A man scratching his shoulder, a kid throwing stones, and dust. It’s very dusty here.”

“What the fuck are you doing here with me?” his voice cracks. “You should leave.”

And so we come to the penultimate, iconic six and half minute uninterrupted take, in which the camera tracks away from Locke reposed on the bed, closing in on the bars across the window, viewing goings on in the dusty exterior. A boy plays with a dog, an old man sits by the wall of the bullring, the girl ambles around, a little car trundles around, someone getting a driving lesson. Then a car pulls up and a man exits. He approaches the girl, then turns before speaking and exits the frame—it seems he goes inside the hotel. We hear doors opening and closing—a muffled shot? The camera then magically exits through the bars and glides around the square before turning back towards the room, Rachel and the police now pulling up. The Girl, curious and alarmed, joins them as they enter Locke’s room.

The policeman asks Rachel if she knows this man. “Is this David Robertson?” “I never knew him.” The same question in a slightly different form to The Girl–“Do you recognize him?” “Yes.” He has lost his identity as David Locke, interchangeable with Robertson, achieving a transference of self, but at great cost.

Antonioni recalled, “I had the idea for the final sequence as soon as I started shooting. I knew, naturally, that my protagonist must die, but the idea of seeing him die bored me. So I thought of a window and what was outside, the afternoon sun. For a second, just for a fraction—Hemingway crossed my mind: ‘Death in the Afternoon.’ And the arena. We found the area and immediately realized this was the place. There were many problems to solve. A zoom was mounted on the camera. But it was only used when the camera was about to pass through the gate.”

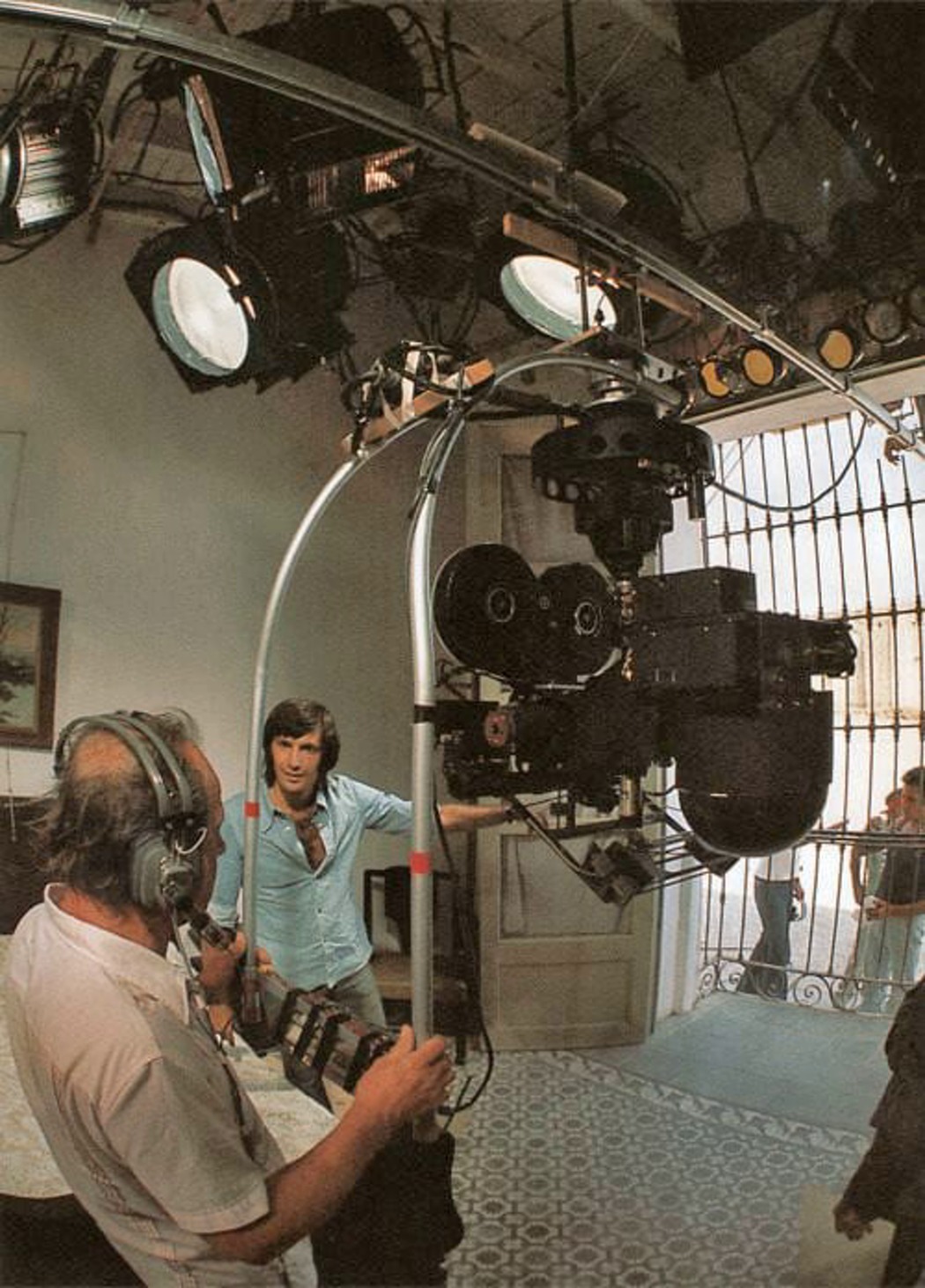

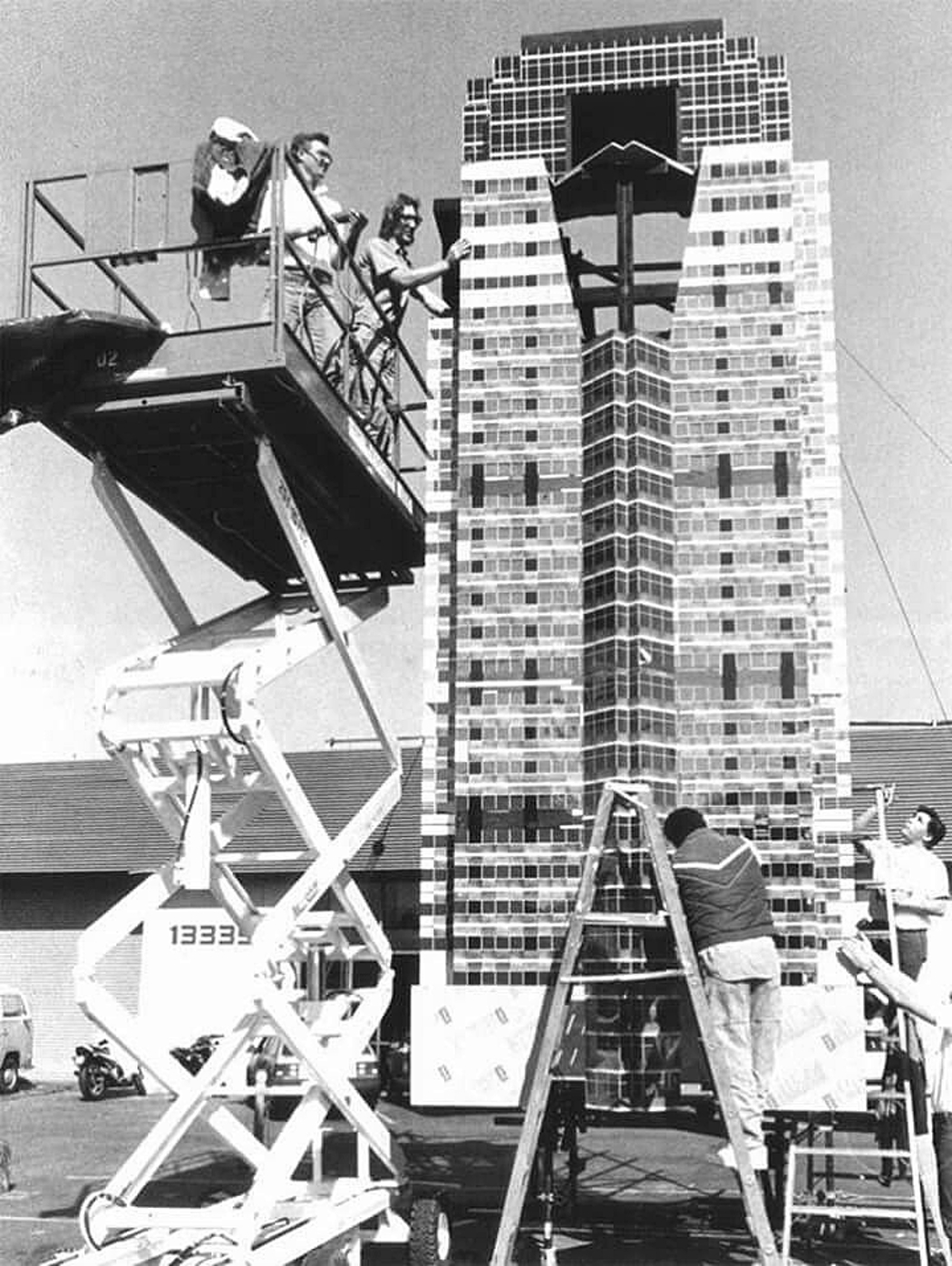

Antonioni built the hotel specifically for the location. A breakdown from Wikipedia, via Dangerous Minds: The shot needed to be taken in the evening towards dusk to minimize the light difference between interior and exterior. Since the shot was continuous, it was not possible to adjust the lens aperture at the moment when the camera passed from the room to the square. As such, the scene could only be shot between 5:00 and 7:30 in the evening. The camera ran on a ceiling track in the hotel room, and when it emerged outside the window it was picked up by a hook suspended on a giant crane that was nearly thirty meters high. A system of gyroscopes had to be fitted to the camera to mask the change from a smooth track to the less smooth and more mobile crane. The bars on the outside of the window were fitted on hinges. As the camera came up to the bars they were swung away at the same time as the hook of the crane attached itself to the camera as it left the tracks. The whole operation was coordinated by Antonioni from a van by means of monitors and microphones to assistants who, in turn, communicated his instructions to the actors and the operators.

Only a few short years later, the Steadicam would have made such a shot much easier.

Michelangelo Antonioni died in 2014. He had long since retired from filmmaking, instead devoting his artistic attentions to painting and drawing, until failing eyesight took this from him. The February 2012 Vanity Fair article “My Dinners with Federico and Michelangelo” by Charlotte Chandler on the filmmaker and his rival Federico Fellini, recounts how, two days before he died, he asked his wife Enrica to drive him around Rome so that he could “see” the places that had meant so much to him. Just the two of them. “He asked her to tell him everything she saw, and he sat with his face pressed against the glass of the car window.” The world was not ugly or dirty to Antonioni, like the blind man in Locke’s story—instead always mysterious, flowing, unknowable. And worth seizing, if only for a fleeting moment, in a doomed car chase across Europe, or a lifetime. He died two days later at the age of 94, holding hands with his wife sat by the window of their apartment.

Tim Pelan was born in 1968, the year of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (possibly his favorite film), ‘Planet of the Apes,’ ‘The Night of the Living Dead’ and ‘Barbarella.’ That also made him the perfect age for when ‘Star Wars’ came out. Some would say this explains a lot. Read more »

“I have always written my own scripts, even if what I wrote was the result of discussions with my collaborators. The Passenger, however, was written by someone else. Naturally I made changes to adapt it to my way of thinking and shooting. I like to improvise—in fact, I can’t do otherwise. It is only in this phase—that is, when I actually see it—that the film becomes clear to me. Lucidity and clearness are not among my qualities, if I have any.” —Michelangelo Antonioni

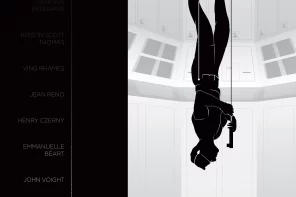

Screenwriter must-read: Mark Peploe, Enrico Sannia & Michelangelo Antonioni’s screenplay for The Passenger [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. A new Blu-ray of The Passenger is due for release on September 22. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

ANTONIONI DISCUSSES ‘THE PASSENGER’

From Filmmakers Newsletter, July 1975.

Did you do the screenplay for The Passenger?

I have always written my own scripts, even if what I wrote was the result of discussions with my collaborators. The Passenger, however, was written by someone else. Naturally I made changes to adapt it to my way of thinking and shooting. I like to improvise—in fact, I can’t do otherwise. It is only in this phase—that is, when I actually see it—that the film becomes clear to me. Lucidity and clearness are not among my qualities, if I have any.In this case, were there any major changes in the screenplay?

The whole idea, the way the film is done, is different. The mood is changed—there is more of a spy feeling, it’s more political.Do you always adapt a piece of material to suit your particular needs?

Always, I got the idea for Blow-Up from a short story by Cortazar, but even there I changed a lot. And The Girlfriends was based on a story by Pavese. But I work on the scripts by myself with some collaboration, and as far as the act of writing is concerned, I always do that myself.I have often felt that the short story is a better medium to adapt to film because it’s compact and about the same length as a film.

I agree. The Girlfriends was based on a short novel, Among Women Only. And the most difficult pages to translate into images were the best pages as far as the novel and the writing were concerned. I mean the best of the pages—the pages I liked the most—were the most difficult. When you have just an idea it’s easier. Putting something into a different medium is difficult because the first medium was there first. In a novel there’s usually too much dialogue—and getting rid of the dialogue is difficult.Do you change the dialogue even further when you’re on the set?

Yes, I change it a lot. I need to hear a line pronounced by the actors.How much do you see of a film when you’re looking at the script? Do you see the locations? Do you see where you’re going to work with the film?

Yes, more or less. But I never try to copy what I see because this is impossible. I will never find the exact counterpart of my imagination.So you wipe the slate clean when you’re lookingfor your location?

Yes. I just go and look. I know what I need, of course. Actually, it’s very simple.Then you don’t leave the selection of location up to your assistants?

The location is the very substance of which the shot is made. Those colors, that light, those trees, those objects, those faces. How could I leave the choice of all this to my assistants? Their choices would be entirely different from mine. Who knows the film I am making better than me?Was The Passenger shot entirely on location?

Yes.I believe most of your other films were too. Why do you have such a strong preference for location shooting?

Because reality is unpredictable. In the studio everything has been foreseen.One of the most interesting scenes in the film is the one which takesplace on the roof of the Gaudi cathedral in Barcelona. Why did you choose this location?

The Gaudi towers reveal, perhaps, the oddity of an encounter between a man who has the name of a dead man and a girl who doesn’t have any name. (She doesn’t need it in the film.)I understand that in Red Desert you actually painted the grass and colored the sea to get the effects you wanted. Did you do anything similar in The Passenger?

No. In The Passenger I have not tampered with reality. I looked at it with the same eye with which the hero, a reporter, looks at the events he is reporting on. Objectivity is one of the themes of the film. If you look closely, there are two documentaries in the film, Locke’s documentary on Africa and mine on him.What about the sequence where Nicholson is isolated in the desert? The desert is especially striking, and the color is unusually intense and burning. Did you use any special filters or forced processing to create this effect?

The color is the color of the desert. We used a filter, but not to alter it; on the contrary, in order not to alter it. The exact warmness of the color was obtained in the laboratory by the usual processes.Did shooting in the desert with its high temperatures and blowing sand create any special problems for you?

Not especially. We brought along a refrigerator in which to keep the film, and we tried to protect the camera from the blowing sand by covering it in any possible way.How do you cast your actors?

I know the actors, I know the characters of the film. It is a question of juxtaposition.Specifically, why did you choose Jack Nicholson and Maria Schneider?

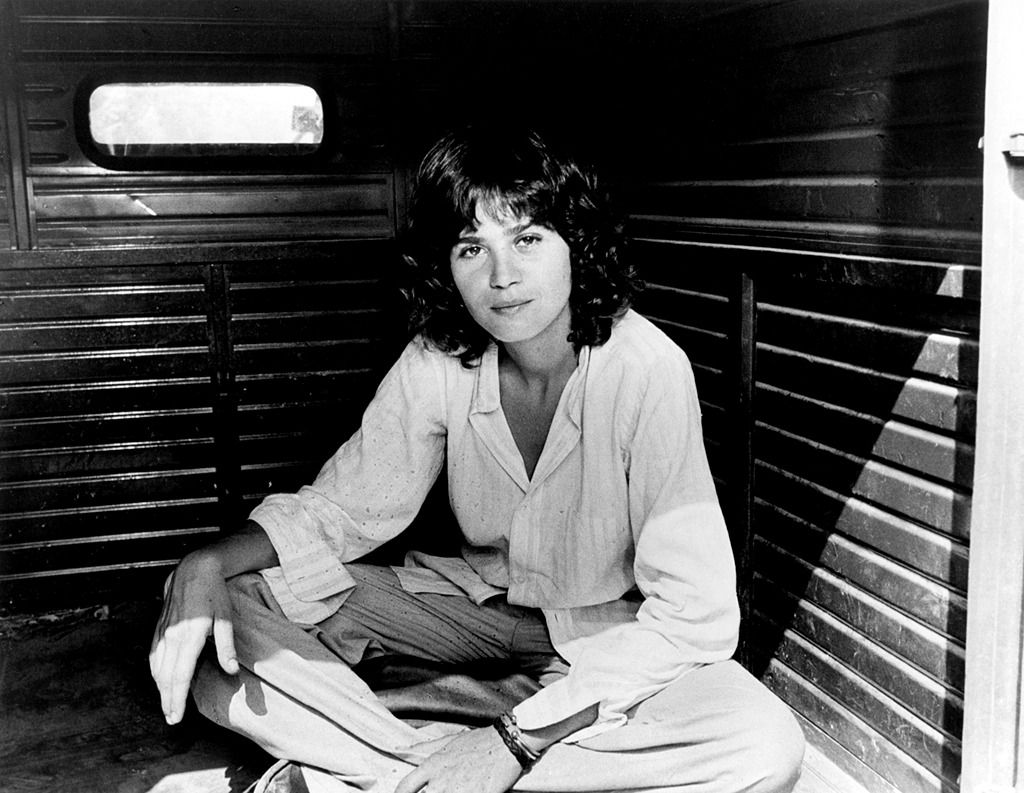

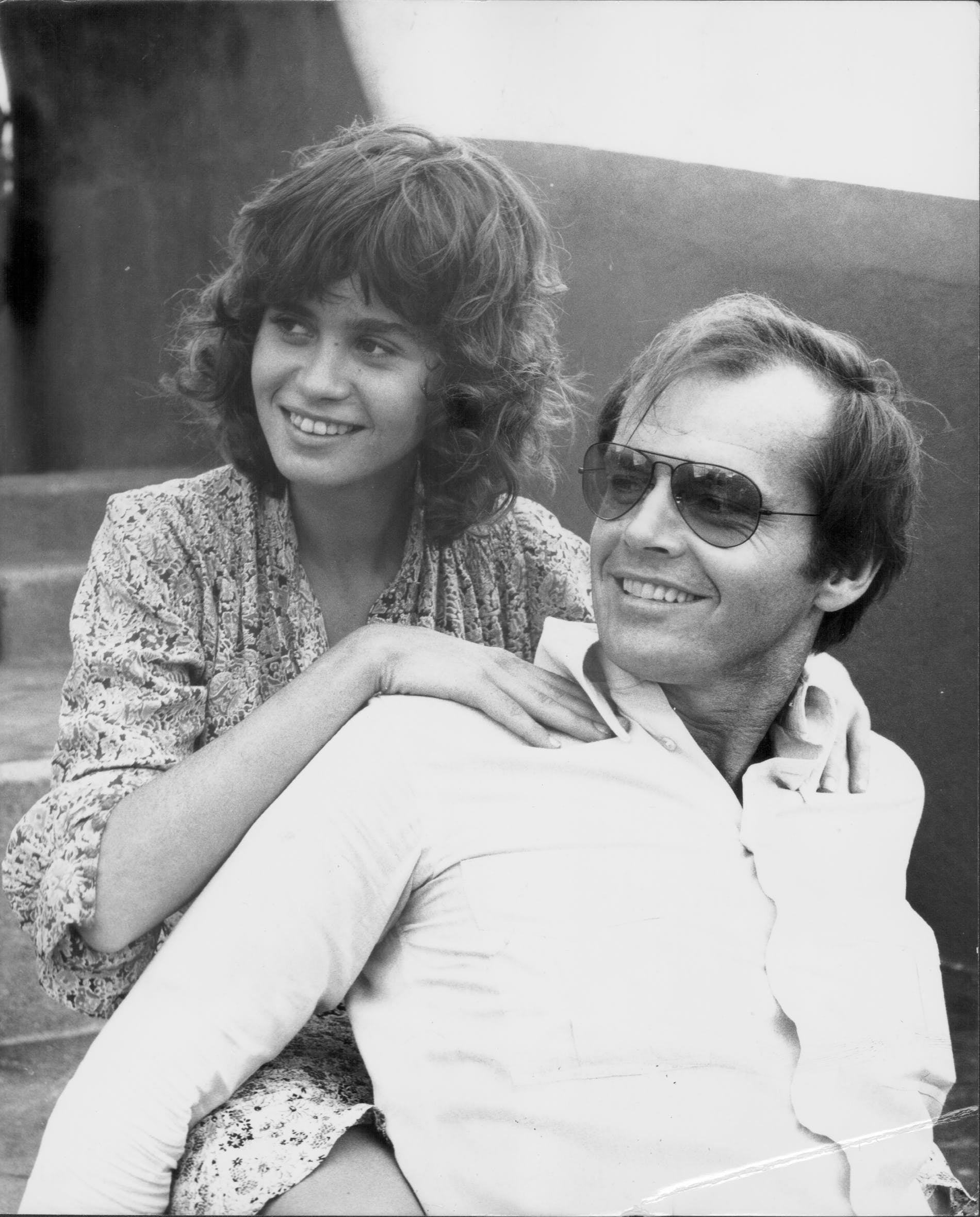

Jack Nicholson and I wanted to make a film together, and I thought he would be very good, very right for this part. The same for Maria Schneider. She was my understanding of the girl. And I think she was perfect for the role. I may have changed it a bit for her, but that is a reality I must face: you can’t invent an abstract feeling. Being a “star” is irrelevant—if the actor is different from the part, if the feeling doesn’t work, even Jack Nicholson won’t get the part.Are you saying that Nicholson acts like a star, that he’s hard to work with?

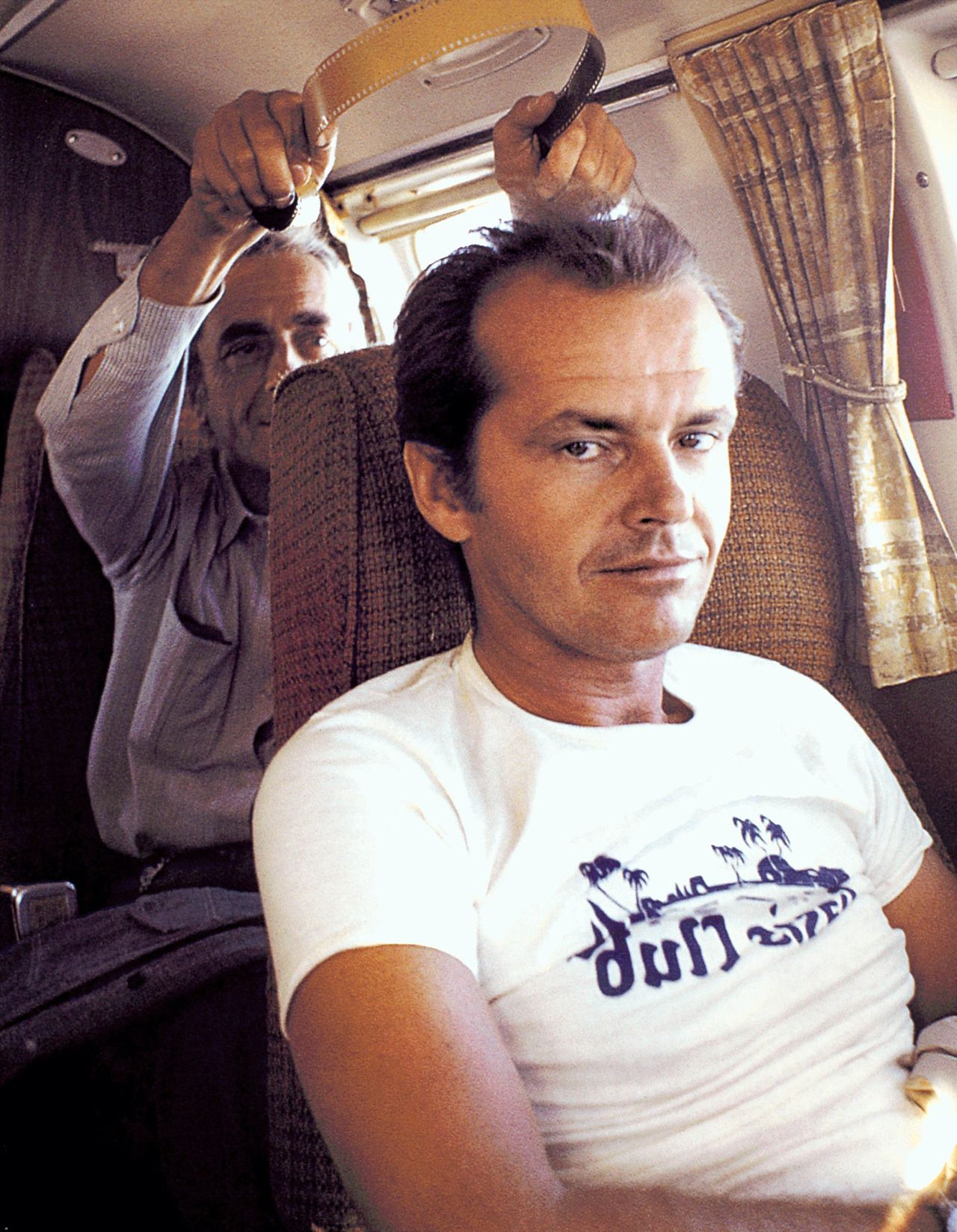

No. He’s very competent and a very, very good actor, so it’s easy to work with him. He’s intense, yet he doesn’t create any problems—you can cut his hair (I didn’t), he’s not concerned about his “good” side or whether the camera is too high or too low; you can do whatever you want.You once said that you see actors as part of the composition; that you don’t want to explain the characters’ motivations to them but want them to be passive. Do you still handle actors this way?

I never said that I want the actors to be passive. I said that sometimes if you explain too much, you run the risk that the actors become their own directors, and this doesn’t help the film. Nor the actor. I prefer working with the actors not on an intellectual but on a sensorial level. To stimulate rather than teach. First of all, I am not very good at talking to them because it is difficult for me to find the right words. Also, I am not the kind of director who wants “messages” on each line. So I don’t have anything more to say about the scene than how to do it. What I try to do is provoke them, put them in the right mood. And then I watch them through the camera and at that moment tell them to do this or that. But not before. I have to have my shot, and they are an element of the image—and not always the most important element. Also, I see the film in its unity whereas an actor sees the film through his character. It was difficult working with Jack Nicholson and Maria Schneider at the same time because they are such completely different actors. They are natural in opposite ways: Nicholson knows where the camera is and acts accordingly. But Maria doesn’t know where the cam era is—she doesn’t know anything; she just lives the scene. Which is great. Sometimes she just moves and no one knows how to follow her. She has a gift for improvising, and I like that—I like to improvise.Then you don’t preplan what you are going to do on the set? You don’t sitdown the evening before or in the morning and say, ‘I’m going to do this and this”?

No. Never, never.You just let it happen as you’re on the set?

Yes.Do you at least let your actors rehearse a scene first, or do you just go right into it?

I rehearse very little—maybe twice, but not more. I want the actors to be fresh, not tired.What about camera angles and camera movement? Do you carefully pre-plan in this area?

Very carefully.Are you able to make decisions about print takes very soon, or do you—?

Immediately.Then you don’t shoot a lot of takes?

No. Three. Maybe five or six. Sometimes we may do fifteen, but that is very rare.Would you be able to estimate how much footage you shoot per day?

No.Just whatever you can accomplish?

In China I made as many as eighty shots in one day, but that was very different work; I had to rush.How long did it take to do the final scene of The Passenger?

Eleven days. But that was not because of me but because of the wind. It was very windy weather and so difficult to keep the camera steady.One critic has said that the final seven-minute sequence is destined to become a classic of film history. Can you explain how you conceived it?

I had the idea for the final sequence as soon as I started shooting. I knew, naturally, that my protagonist must die, but the idea of seeing him die bored me. So I thought of a window and what was outside, the after noon sun. For a second, just for a fraction—Hemingway crossed my mind: “Death in the Afternoon.” And the arena. We found the arena and immediately realized this was the place. But I didn’t yet know how to realize such a long shot. I had heard about the Canadian camera, but I had no first-hand knowledge of its possibilities. In London, I saw some film tests. I met with the English technicians responsible for the camera and we decided to try. There were many problems to solve. The biggest was that the camera was 16mm and I needed 35mm. To modify it would have involved modifying its whole equilibrium since the camera is mounted on a series of gyroscopes. However. I succeeded in doing it.Did you use a zoom lens or a very slow dolly?

A zoom was mounted on the camera. But it was only used when the camera was about to pass through the gate.It’s interesting how the camera moves toward the man in the center against the wall but we never get to see him, the camera never focuses on him.

Well, he is part of the landscape, that’s all. And everything is in focus—everything. But not specifically on him. I didn’t want to go closer to anybody. The surprise is the use of this long shot. You see the girl outside and you see her movements and you understand very well without going closer to her what she’s doing, maybe what her thoughts are. You see, I am using this very long shot like closeups, the shot actually takes the place of closeups.Did you cover that shot in any other way or was this your sole commitment?

I had this idea of doing it in one take at the beginning of the shoot ing and I kept working on it all during the shooting.How closely do you work with your cinematographer?

Who is the cinematographer? We don’t have this character in Italy.How big a crew do you work with?

I prefer a small crew. On this one I had a big crew—forty people but we had union problems so it couldn’t be smaller.How important is your continuity girl to your work?

Very important. Because we have to change in the middle, we can’t go chronologically.How closely do you work with your editor?

We always work together. However, I edited Blow-Up myself and the first version of The Passenger as well. But it was too long and so I redid it with Franco Arcalli, my editor. Then it was still too long, so I cut it by myself again.How closely does the edited version reflect what you had in mind when you were shooting?

Unfortunately, as soon as I finish shooting a film I don’t like it. And then little by little I look at it and start to find something. But when I finish shooting it’s like I haven’t shot anything. Then when I have my material—when it’s been shot in my head and on the actual film—it’s like it’s been shot by someone else. So I look at it with great detachment and then I start to cut. And I like this phase. But on this one I had to change a lot because the tIrst cut was very long. I shot much more than I needed because I had very little time to prepare the film—Nicholson had some engagements and I had to shoot very quickly.So you didn’t have time before the shooting to cut your screenplay down to size.

Right. I shot much more than was necessary because I didn’t know what I would need. So the first cut was very long—four hours. Then I had another that ran two hours and twenty minutes. And now it’s two hours.Do you shoot lip sync—record the sound on location?

Yes.What about dubbing?

A little—when the noise is too much.The soundtrack is an enormously important part of your films. For L’avventura you recorded every possible shading if the sound if the sea. Did you do anything similar for The Passenger?

My rule is always the same: For each scene, I record a soundtrack without actors.Sometimes you make critical plot points by using sound alone. For instance, in the last sequence we have only the sound if the opening door and what might be a gunshot to let us know the protagonist has been killed. Would you comment on this?

A film is both image and sound. Which is the most important? I put them both on the same plane. Here I used sound because I could not avoid looking at my hero—I could not avoid hearing the sounds connected with the actual killing since Locke, the killer, and the camera were in the same room.You use music only rarely in the film, but with great effectiveness. Can you explain how you choose which moments will be scored?

I can’t explain it. It is something I feel. When the film is finished, I watch it a couple of times thinking only about the music. In the places where I feel it is missing, I put it in—not as score music but as source music.Who do you admire among American directors?

I like Coppola; I think The Conversation was a very good film. I like Scorsese; I saw Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore and liked it very much it was a very simple but very sincere film. And you have Altman and California Split—he’s a very good observer of California society. And Steven Spielberg is also very good.I have the impression from your films that your people tend to just appear full-blown in a particular situation, that there’s not much if a past to your characters. For instance, we find Nicholson in an alienated place with no roots behind him. And the same for the girl; she’s just there. It’s as though people arc just immediately in an immediate present. There’s no background to them, as it were.

I think it’s a different way of looking at the world. The other way is the older way. This is the modern way of looking at people. Today everyone has less background than in the past. We’re freer. A girl today can go anywhere, just like the one in the film, with just one bag and no thoughts for her family or past. She doesn’t have to carry any baggage with her.You mean moral baggage?

Precisely. Moral, psychological luggage. But in the older movies people have homes and we see these homes and the people in them. You see Nicholson’s home, but he’s not tied down, he’s used to going all over the world.Yet you seem to find the struggle for identity interesting.

Personally, I mean to get away from my historical self and find a new one. I need to renew myself this way. Maybe this is an illusion, but I think it is a way to reach something new.I was thinking if the television journalist like Mr. Locke getting bored with life. Then there’s no hope for anything because that’s one if the more inter esting careers.

Yes, in a way. But it’s also a very cynical career. Also, his problem is that he is a journalist—he can’t get involved in everything he reports because he’s a filter. His job is always to talk about and show something or someone else, but he himself is not involved. He’s a witness not a protagonist. And that’s the problem.Do you see any similarity between your role as a film director and the role of Locke in the film?

In this film it may be yes; it’s part of the film. But it’s different in a way. In The Passenger I tried to look at Locke the way Locke looks at real ity. After all, everything I do is absorbed in a kind of collision between myself and reality.Some people think of film as being the most real of the arts and some think it’s purely illusion, a fake, because everything in a movie is still pictures. Can you speak a bit about this in relation to The Passenger?

I don’t know if I could speak about it—if I could do the same thing with words I would be a writer and not a film director. I don’t have any thing to say but perhaps something to show. There’s a difference. That’s why it’s very difficult for me to talk about my films. What I want to do is make the film. I know what I have to do. Not what I mean. I never think the meaning because I can’t.You’re a film director and you make images, yet I find that in your films the keypeople have a problem with seeing—they’re trying to find things or they”ve lost something. Like the photographer in Blow-Up trying to find reality in his own work. Are you, as a director working in this medium, frustrated at not being able to find reality?

Yes and no. In some ways I capture reality in making a film—at least I have a film in my hands, which is something concrete. What I am facing may not be the reality I was looking for, but I’ve found someone or something every time. I have added something more to myself in making the film.Then it’s a challenge each time?

Yes! I fight for it. Can you imagine? I lost my male character in the desert before the ending of the film because Richard Harris went away without telling me. The ending was supposed to be all three of them—the wife, the husband, and the third man. So I didn’t know how to finish the film. I didn’t stop working during the day, but at night I would walk around the harbor thinking until I finally came up with the idea for the ending I have now. Which I think was better than the previous one—fortunately.Have you ever wanted to make an autobiographical film?

No. And I’ll tell you why: Because I don’t like to look back; I always look forward. Like everyone, I have a certain number of years to live, so this year I want to look forward and not back—I don’t want to think about the past years, I want to make this year the best year of my life. That is why I don’t like to make films that are statements.It’s been said that in a certain sense a director makes the same film all his fife—that is, explores the different aspects of a given theme in a variety of ways throughout his pictures. Do you agree with this? Do you feel it’s true for your work?

Dostoevskij said that an artist only says one thing in his work all through his life. If he is very good, perhaps two. The liberty of the paradoxical nature of that quotation allows me to add that it doesn’t completely apply to me. But it’s not for me to say.

Jack Nicholson’s audio readings of two Antonioni essays (“L’Avventura: A Moral Adventure,” “Reflections on the Film Actor”) as well as his six minutes’ worth of jolly recollections shooting The Passenger with Antonioni in 1974. This recording originally appeared in the Criterion Collection’s 2001 DVD edition of L’Avventura.

LUCIANO TOVOLI, ASC, AIC

Director Michelangelo Antonioni’s existential 1975 neo-noir drama The Passenger (Professione: reporter) exudes a sense of mystery that permeates every frame—carrying over to the production itself, specifically the picture’s penultimate shot. This seven-minute “impossible” camera move—executed by cinematographer Luciano Tovoli, ASC, AIC and a very capable crew—has become stuff of legend. How a cinematographic challenge became a sublime piece of production virtuosity in the hands of Luciano Tovoli, ASC, AIC. —The Passenger: One Epic Shot

ANTONIONI ON THE SEVEN-MINUTE SHOT

The second-to-last take of the film, which lasts approximately seven minutes, called for the use of a special camera, a Canadian invention. I also tried other ways of getting the same idea, but all were shown to be less practical and more artificial. The problem was not so much getting out of the window, but panning the full semicircle of the piazza to end up before the window again. This was made possible by the use of a camera mounted on a series of gyroscopes. Inside the room, the camera moved hanging from a track attached to the ceiling. The cameraman pushed it with his hands on the large curving handles seen in the photo. Once the camera arrived at the wrought-iron grating, the worst problem arose. The grating was hinged, and swung open a second after the bars went off-camera at the sides of the shot. Obviously, I controlled everything—including commands for the zooms and pans-on a monitor that was in a van. From here I gave orders to my assistant with a microphone, and the assistant transmitted them to the actors, extras, cars, and everything else which made the “movement” in the piazza. Behind the hotel there was a huge crane, more than a hundred feet high, from which hung a steel cable. Once the camera was outside the window, it left the track and was simultaneously hooked onto the cable. Naturally, the shift from a fixed support, like the track, to a mobile one, such as the cable, caused the camera to bump and sway while a second cameraman, experienced in this work, took over. This is where the gyroscopes came in: they completely neutralized the bumping and swaying. The shooting of this take required eleven days. There were other difficulties, primarily the wind. The weather was windy and stormy, and a wind storm soon arrived, doing much damage. In order to be independent of the weather, this special camera normally operates in a closed sphere. But the sphere was too big, and would not pass through the window. Doing without the sphere meant exposing ourselves to the vagaries of the weather. But I had no choice. Furthermore, I had shoot between 3:30 and 5:00 p.m. because of the light, which at other hours would have been too strong. You must remember we came from inside to the outside, and the ratio of internal to external light governed the diaphragm opening for the whole shot. Another problem: the camera was a 16mm one. After much discussion, the cameraman was persuaded to try 35mm. They asked me to mount a 400-foot reel, but, as I thought, it was not long enough for the sequence. To use a thousand-foot reel required a new adjustment of the whole gyroscopic equilibrium of the camera. The photos show the work we did to get the final result. A big crowd followed our efforts each day. When, finally, on the eleventh day, we succeeded in obtaining two good takes, there was a long and moving outburst of applause, such as, on the field, greets a player who has made a goal. —Michelangelo Antonioni, The Passenger: One Epic Shot

‘DEAR ANTONIONI’

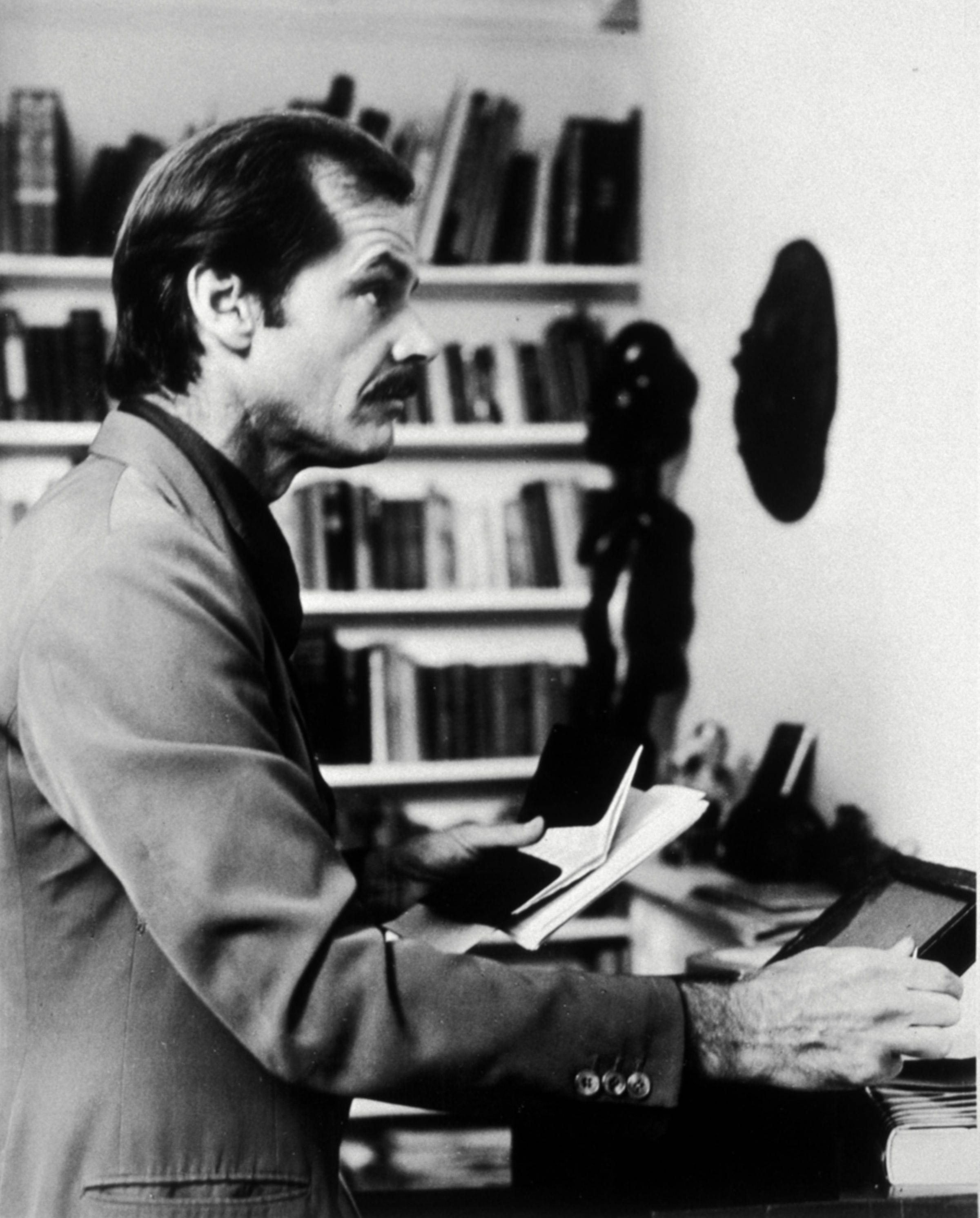

Portrait of Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni. In 1980 the great French philosopher and author Roland Barthes wrote an open letter to Antonioni. It is an appraisal of Antonioni’s place as an artist in the world. Barthes was a revolutionary thinker who, like Antonioni went beyond conventional modes of analysis. Dear Antonioni is linked by that letter, examines the life and work of one of the true masters of the cinema—with contributions and readings from Monica Vitti, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Vanessa Redgrave, Sam Shepard, David Hemmings, Furio Columbo, Alain Cuny, Christine Boissot, Carlo di Palma and Maria Schneider.

MICHELANGELO ANTONIONI: THE EYE THAT CHANGED CINEMA

Sandro Lai compiled interviews, talk show appearances, and award presentations from Italian TV for this 2001 film chronicling most of the director’s career. It hardly qualifies as in-depth analysis of either the man or his films, but it has a lot of historical flavor and some odd bits of trivia (Antonioni once visited John F. Kennedy in the White House to discuss a film about the projected moon landing). Apparently Antonioni shifted to color before much of Italian TV did, because the brief coverage here of Red Desert (1964), Blowup (1966), and Zabriskie Point (1969) is in black and white, and color arrives only with his disputed documentary about China. —Jonathan Rosenbaum

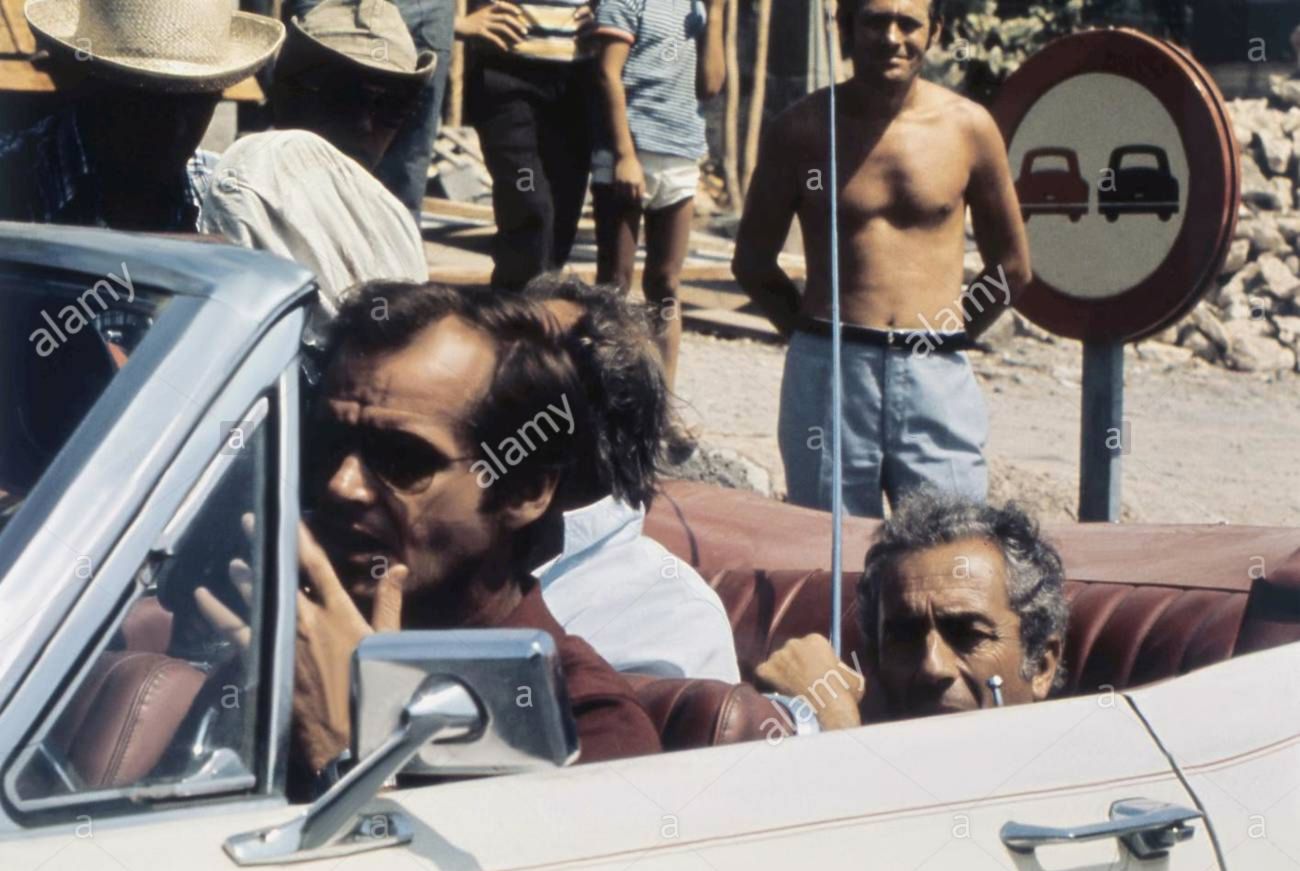

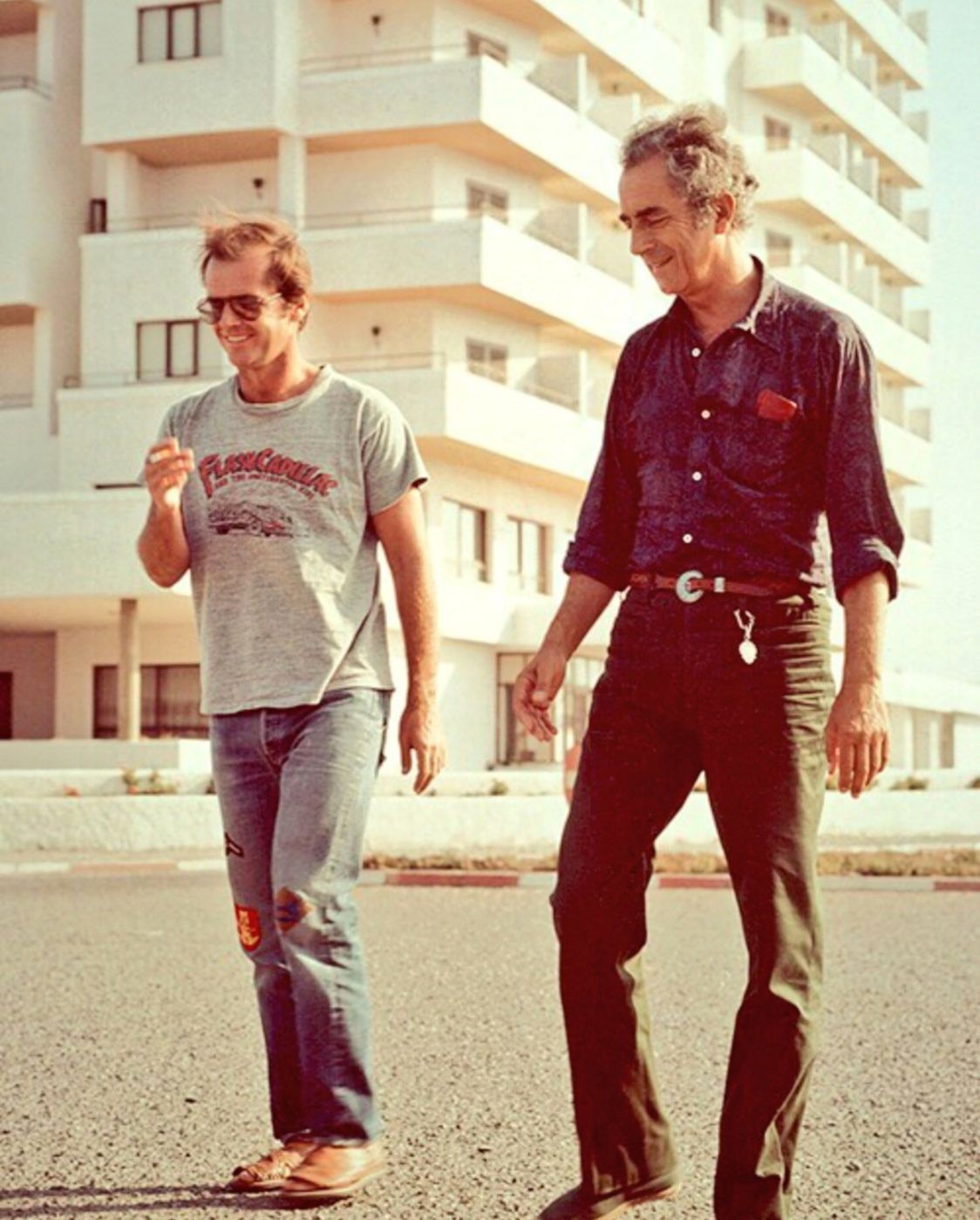

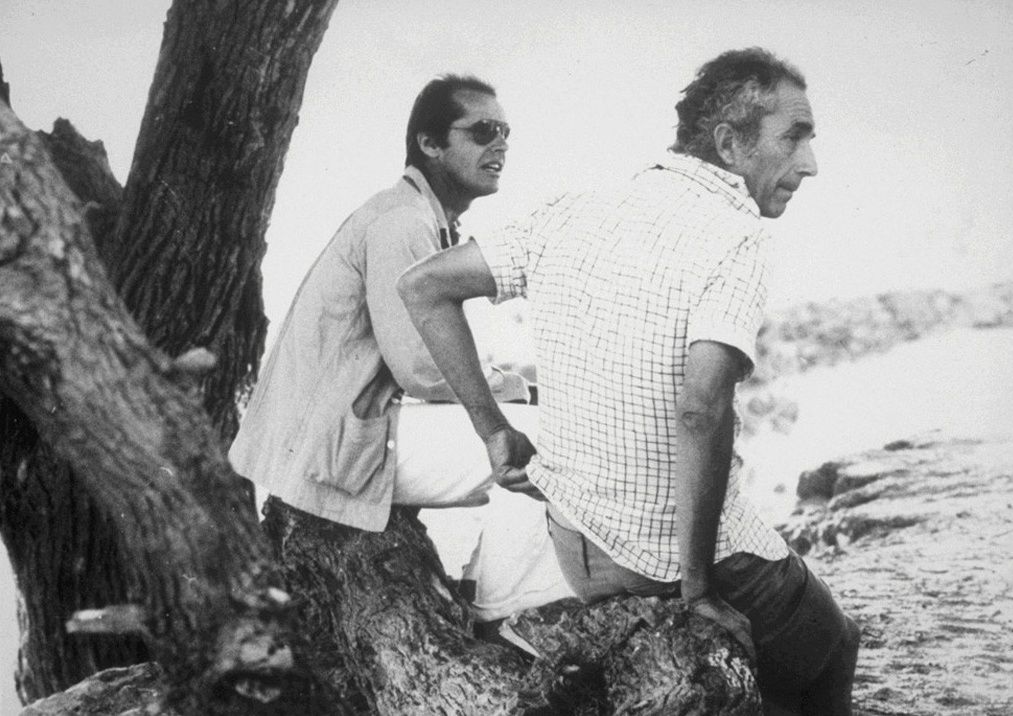

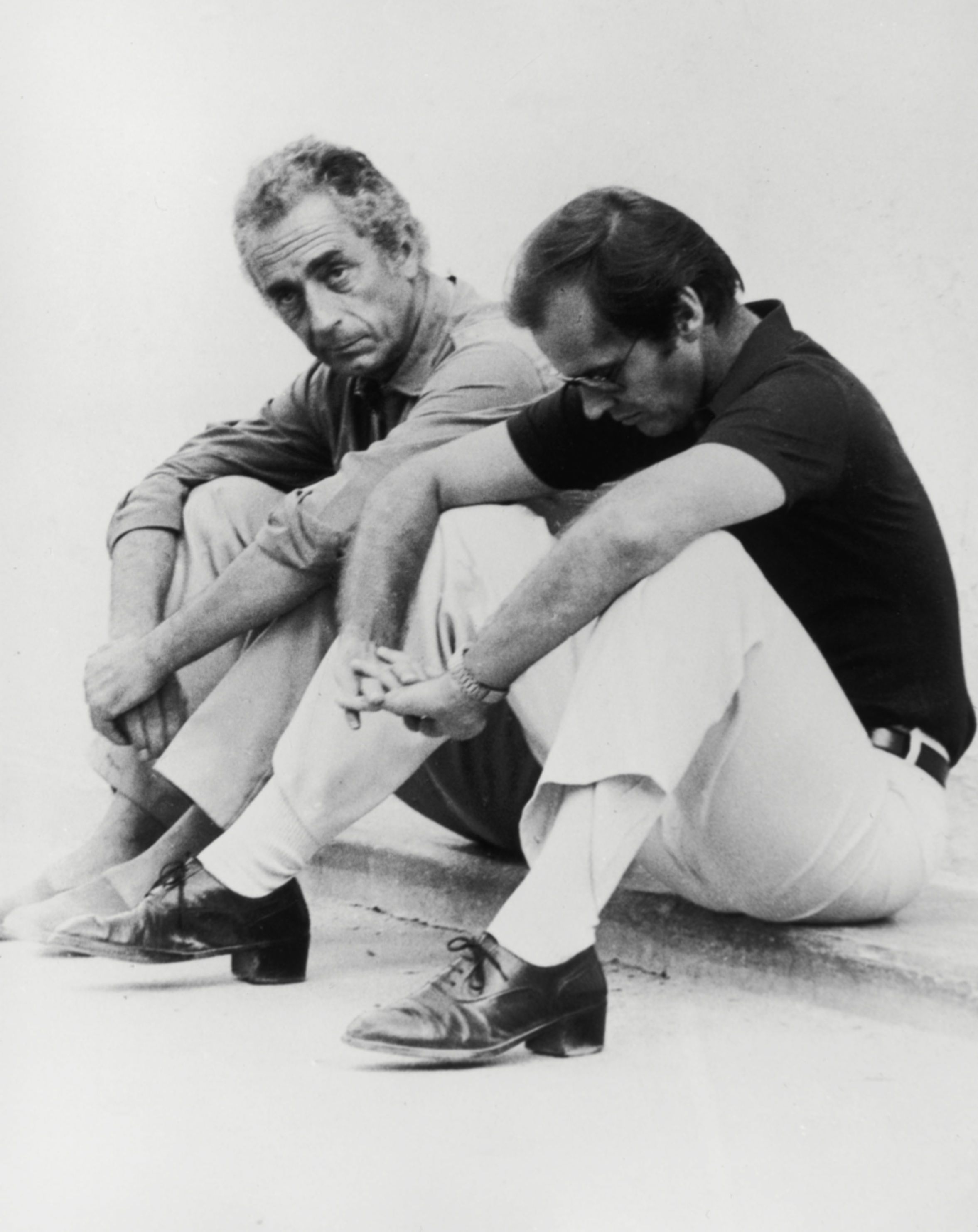

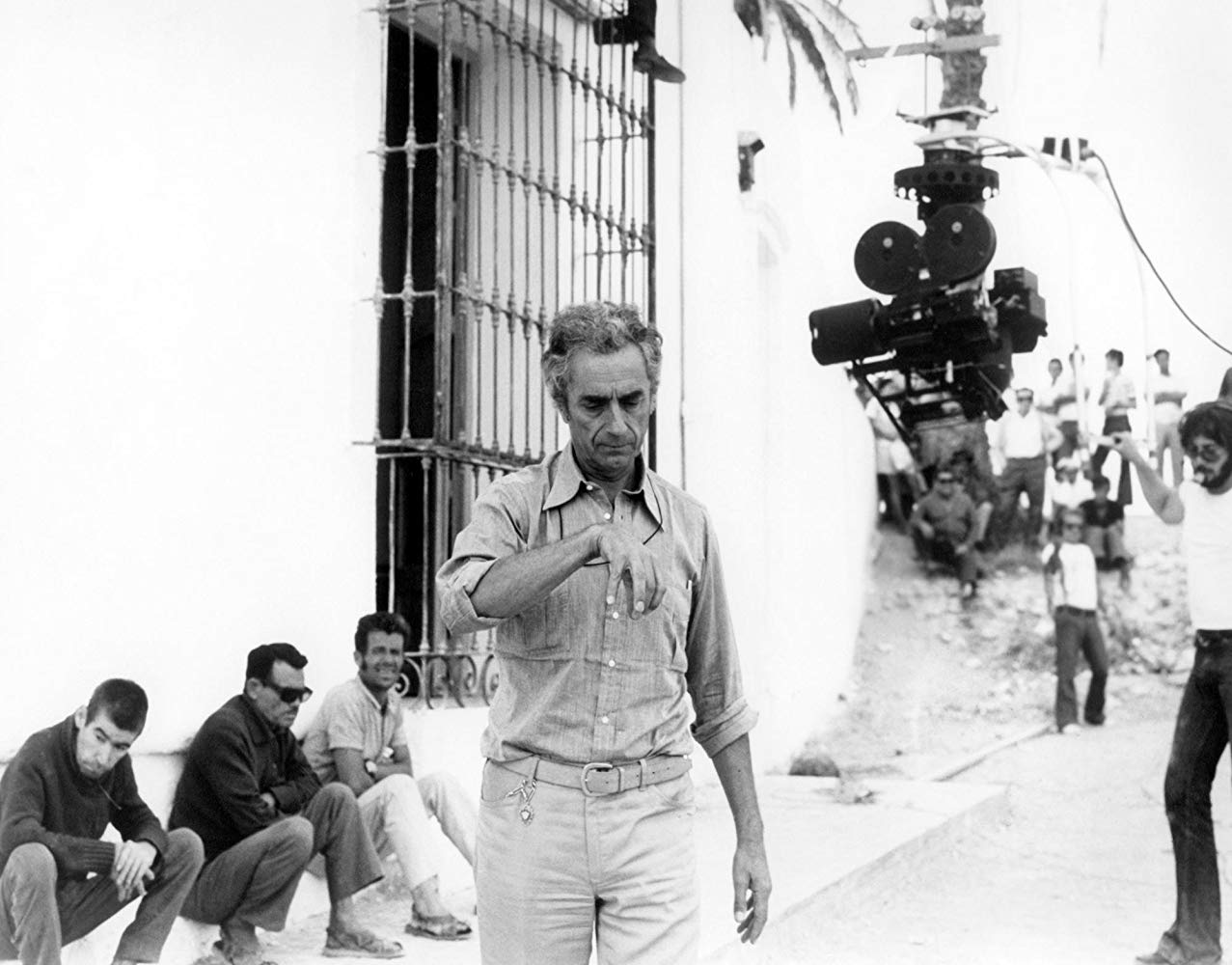

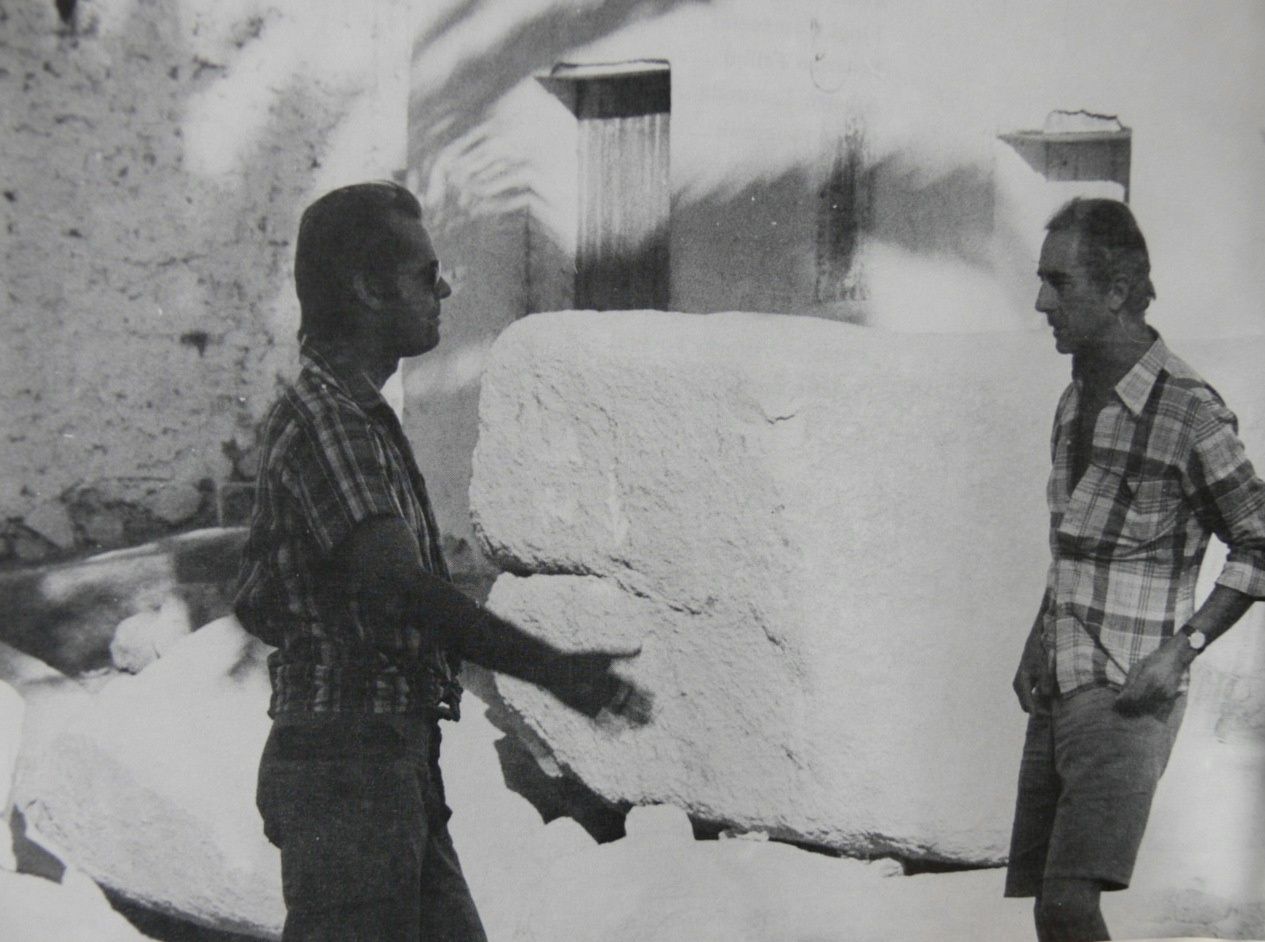

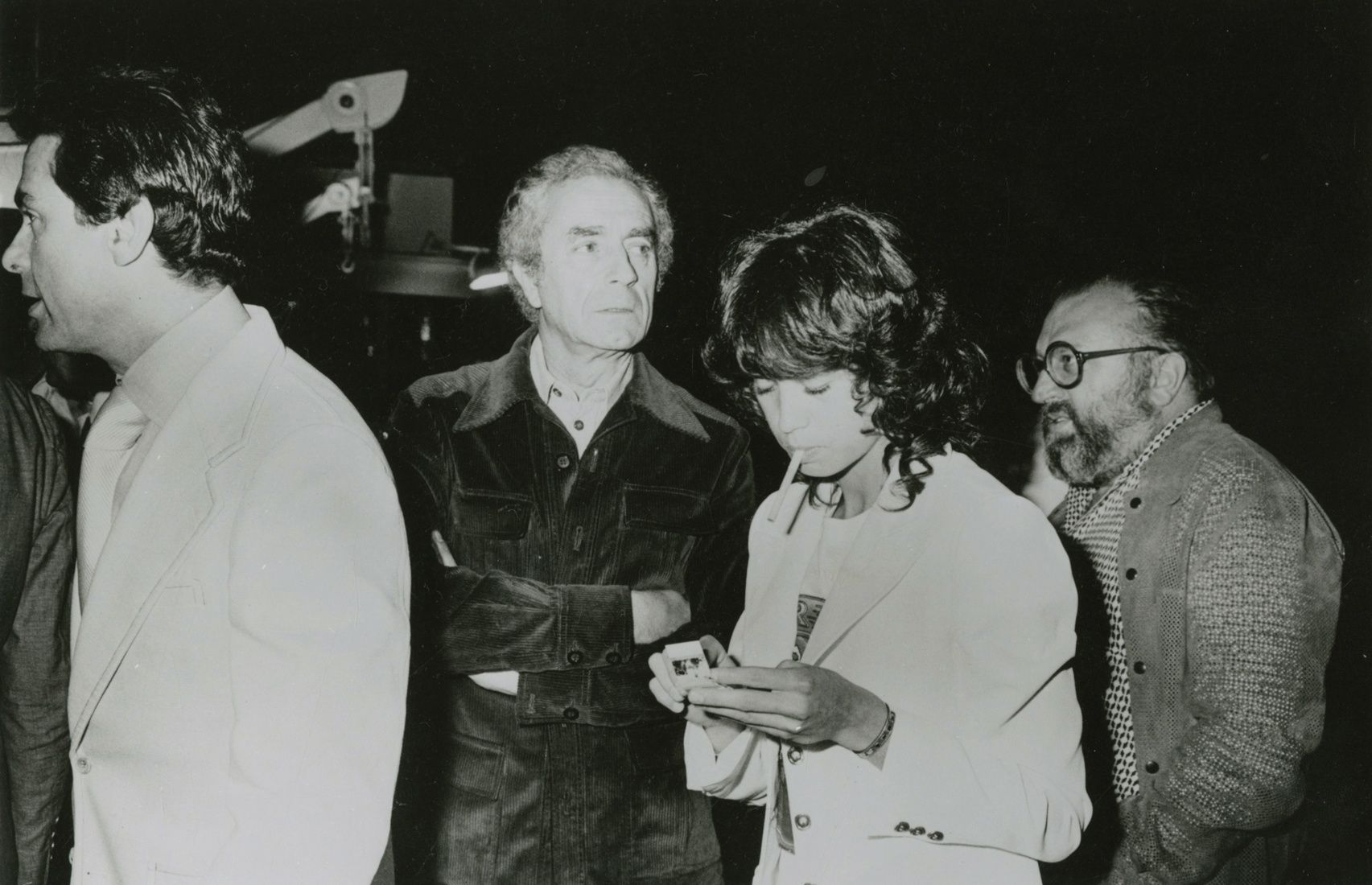

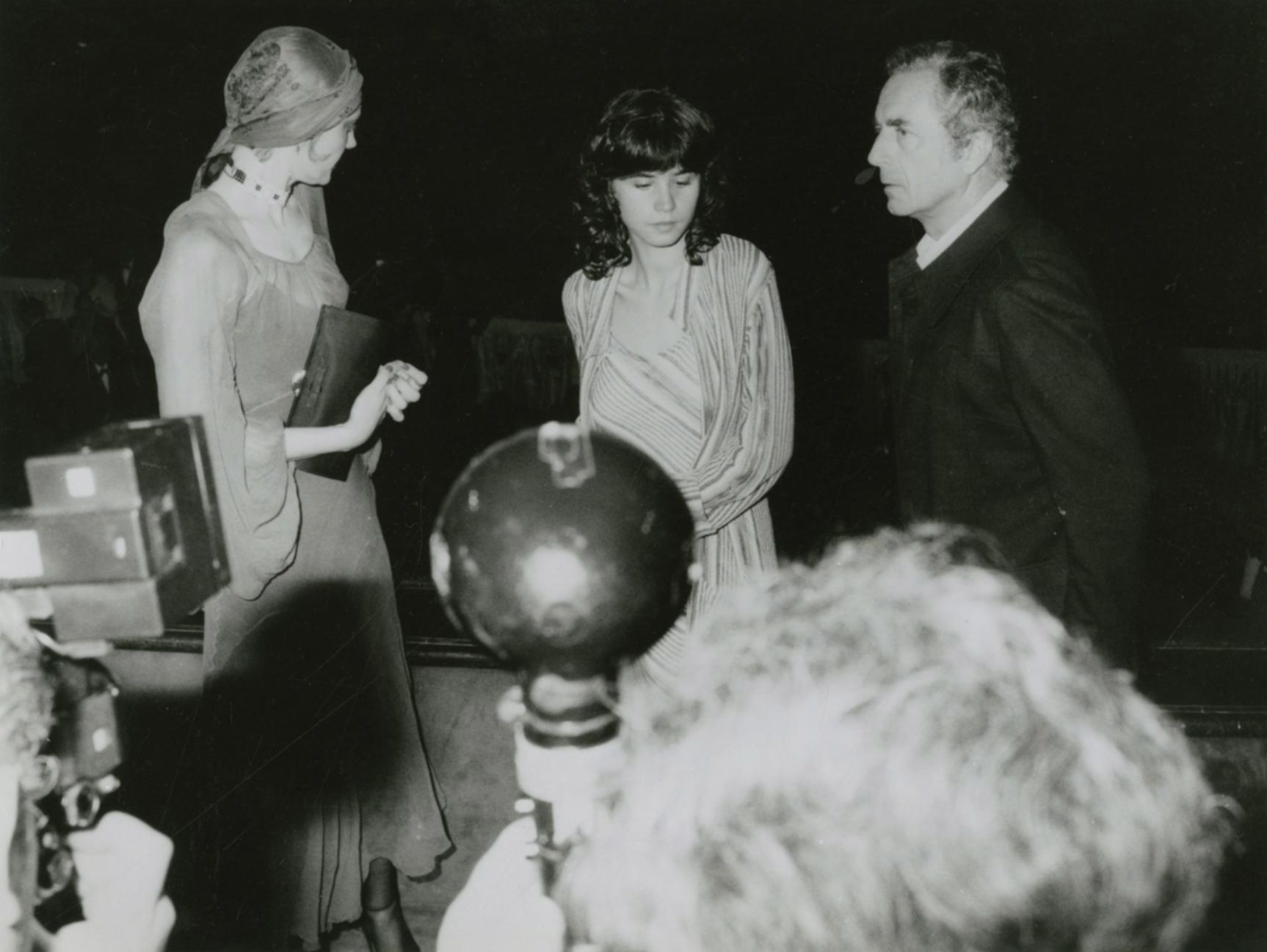

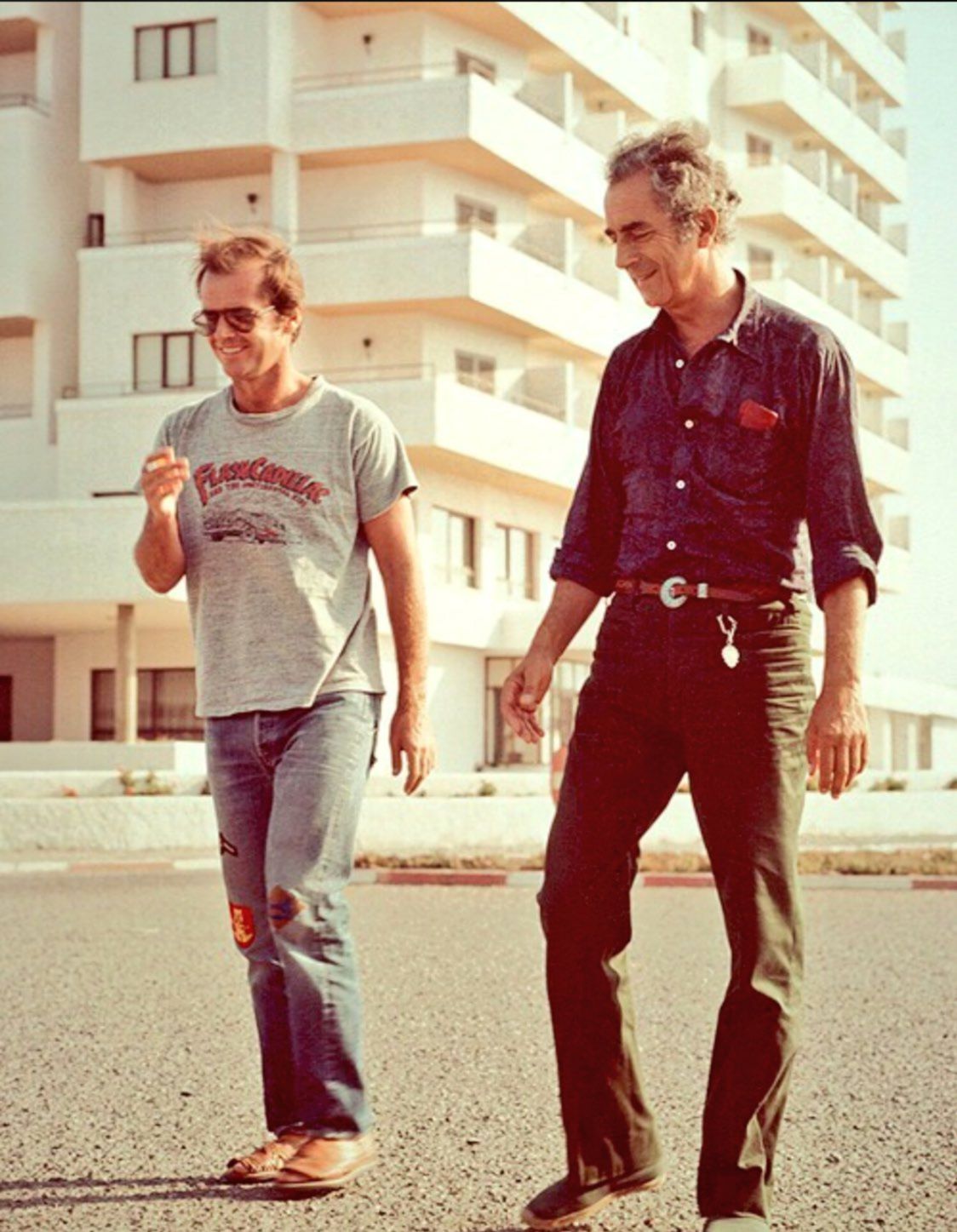

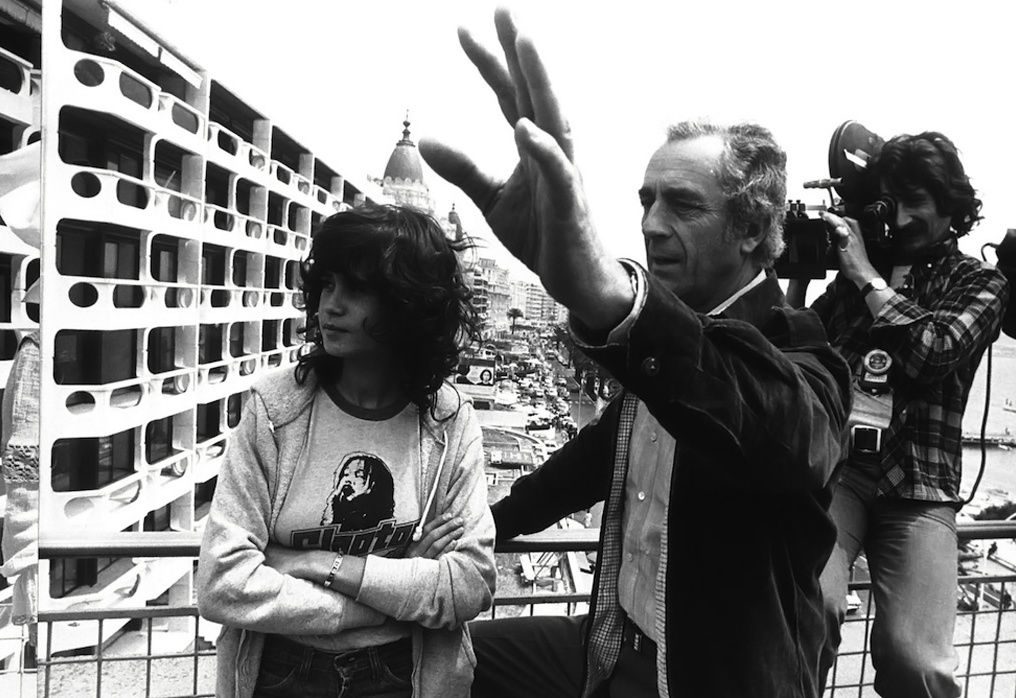

Here are several photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger. Photographed by Floriano Steiner © Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), Compagnia Cinematografica Champion, Les Films Concordia, CIPI Cinematografica S.A. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or donate directly below: