By Tim Pelan

On Sunday 18 February the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) will honor Sir Ridley Scott with the 2018 Fellowship at the EE British Academy Film Awards. Awarded annually, the Fellowship is the highest accolade bestowed by BAFTA upon an individual in recognition of an outstanding and exceptional contribution to film, games or television. Scott’s career has spanned over 40 years, half his lifetime—his debut feature came after a long and lucrative career in advertising, which itself followed on from studies at the Royal College of Art, and a design apprenticeship at the BBC. In 1968, Scott founded the production company Ridley Scott Associates (RSA) with his brother Tony. Growing up in the gruff north of England watching films with his mother, making films was always a secret dream. The Royal College was where he made his first film, Boy and Bicycle, with his brother as the subject. He told DGA Quarterly, “There was no film school there; all there was was a Bolex camera with a windup key in a cupboard with a light meter and instruction book. That was it, that was the only indication that they were even trying to be a film school. I wrote a script and they said, ‘Okay, you’ve got the camera for six weeks.’ So in the summer holidays, I went back home, and I fundamentally ruined my brother Tony’s holiday by hauling him out of bed at 5 or 6 o’clock in the morning and saying, ‘Come on, I’ve got the car, let’s get going.’ He played the boy on the bicycle. We’d drive up to Hartlepool with the gear that I’d manage to rent at 12 pounds a week. Arriflex legs, no-battery stuff because it was all like winding a clock. The whole film cost 60 quid.” Scott continued the self-financed approach when he determined to make his first feature years later, seeking out properties in the public domain to cut costs. Joseph Conrad’s The Duel (also known as The Point of Honour) was a short story which already had a screenplay by Gerald Vaughan-Hughes. Scott bought it and together he and producer David Puttnam persuaded Paramount to chip in an extra $800,000.00. Unusually for a first film, he got a pretty free ride to do what he wanted in the picturesque, rain-swept Dordogne region of France, creating a sweeping epic on a shoestring, winning the 1977 Cannes Best Debut Award to boot.

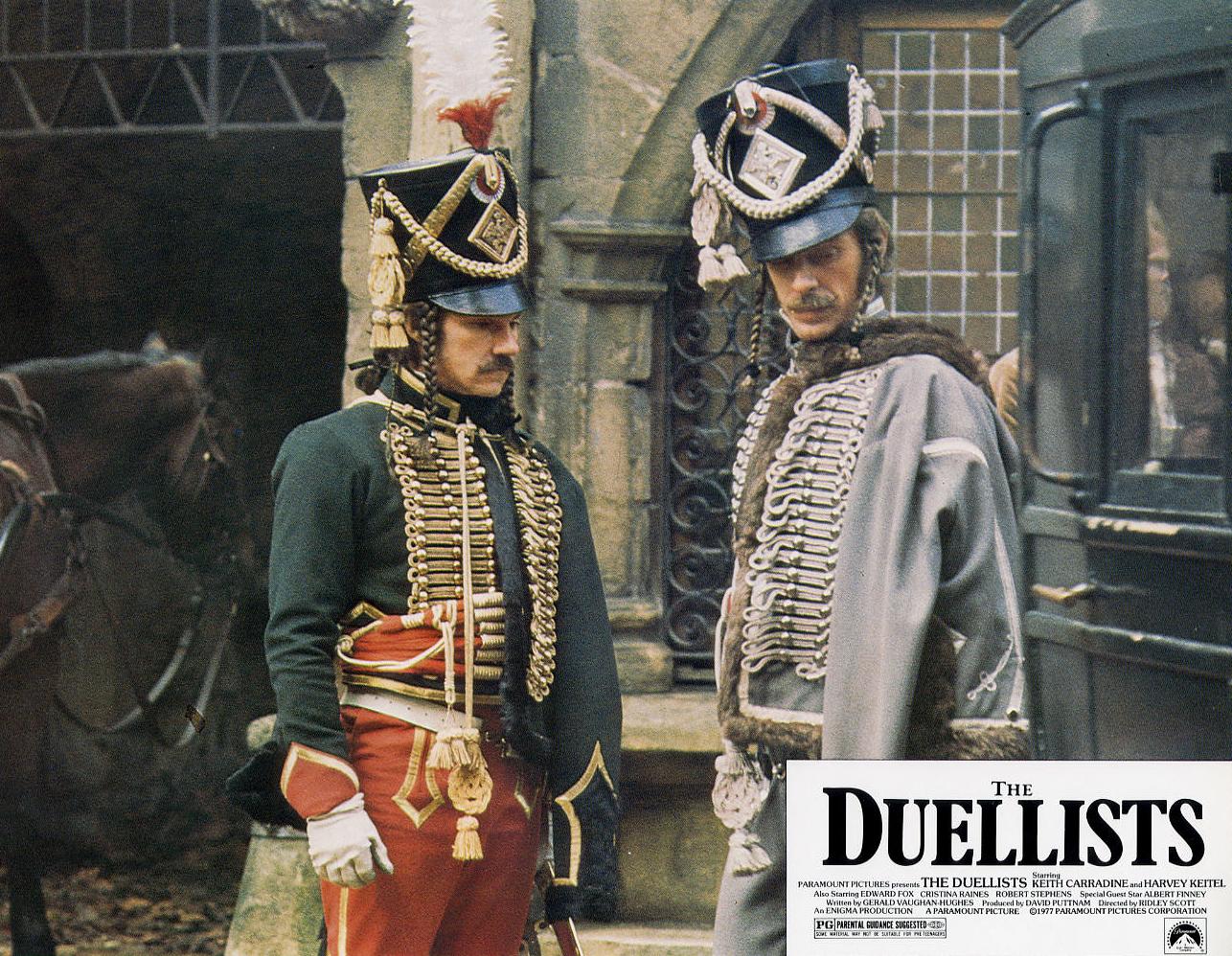

With The Duellists, as Scott renamed the property, an imagined slight leads to a fifteen-year magnificent obsession during the rise and fall of Napoleon’s Empire. Scott’s film charts an obsessive conflict, reluctant on one part, between two officers of Napoleon’s Grande Armee, from 1800 to his defeat and exile on St. Helena post-1815. When Lieutenant Gabriel Feraud (Harvey Keitel) runs through the nephew of Strasbourg’s Mayor in a fencing duel (played by Alec Guinness’s son, Matthew Guinness), Lieutenant Armand d’Hubert (Keith Carradine) is dispatched to summon him to house arrest. He does so discreetly at a social gathering in a ladies salon, but Feraud takes this as a personal insult to his honor. He immediately challenges Armand to a duel upon arrival at his quarters in town, beginning a long-simmering, contumelious and pointless quarrel that will come to define them both, for better or worse. At one point, while bathing his wounded and battered body after a brutal encounter, Armand’s lover Laura (Diane Quick) asks “What is honor?” He gropes for meaning to a life that is slipping beyond his control: “Honour is indescribable… unchallengeable.” Feraud is strutting, prickly and aware perhaps of his more humble beginnings, which explains his devotion to L’Emperor. Even over time transposing the original reason for his enmity to a belief Armand was never a true believer in Bonaparte. He is always seen in the company of men, attempting to best them at cards or feats of strength. When Laura comes to plead with him after an early duel, he makes a clumsy joke. Protecting himself with a blade, he tells her and the assembled company, “I knew a man who was stabbed to death by a woman; gave him the surprise of his life.” Laura coolly replies, “I once knew a woman who was beaten to death by a man. I don’t think it surprised her at all.” Curious how words and scenes from the past can come to define later events, like the #MeToo situation currently in the news.

Armand, by contrast, is at ease in the company of women, gracious and charming. He also now attracts the attention of ladies as a hellhound, much to his chagrin. He is no coward, but comes to dread Feraud’s shadow across his path, at one point relieved a temporary disparity in rank puts dueling between them out of the question. Feraud’s challenging is a microcosm of the specter of Bonaparte upon the European powers. At one point Armand’s friend Dr. Jacquin (Tom Conti) wryly observes “duels between Nations take absolute precedence.” Armand is desperate for an escape from the madness, to live freely, but his own personal honor will not allow him to back down, eventually causing him to lose Laura. Feraud is like the Terminator—he absolutely will not stop until Armand is dead. But with the changing fortunes of France, and Armand’s realist approach to politics as opposed to Feraud’s fanatacism, it is Armand who will come to hold Feraud’s fate in his hand, even as he is sought out one last time. Happily married with a Royalist Generalship, he has Feraud’s name removed from a list of Bonapartists headed for the guillotine. He alone will determine his fate.

The appeal of The Duellists as a subject to Scott was that it was “a very nice pocket edition of the Napoleonic Wars—the collision of chivalry and aggression,” as he told Empire in 2005. “It was under 80 pages and somehow encapsulated the craziness of an argument and how at the end of a 20-year period one of them forgot the reason why they were fighting. Isn’t that familiar? When we found the location most appropriate for the film, Salat in the Dordogne, I discovered that both characters in the book were based on men who’d actually lived. Conrad had found this newspaper article—after 27 years one of the guys died of natural causes and they acknowledged his death with this article.”

Scott originally wanted Michael York and Oliver Reed for the mutual antagonists, but their salaries were prohibitive, settling instead on Carradine and Keitel, who inhabit the roles in their own pleasingly modern manner, one languid and anxious, one tightly wound and seething with imagined sleight. Carradine at the time was finishing a musical tour for his Oscar-winning number “I’m Easy,” from Robert Altman’s film Nashville, which delayed filming until the winter. Scott persuaded Keitel that filming would be interspersed with relaxing offtime enjoying fine wines from the region and expensive cigars. A superb supporting cast fleshes out the film too. Albert Finney appeared without a fee as the real-life Joseph Fouché, Minister of Police, being instead presented with a framed £25.00 cheque, with the notation, “Break glass in case of dire need.” As well as filming in France, Scott also filmed in the Cairngorms in Scotland for the scenes of the retreat from Russia. His DoP from his advertising days, Frank Tidy, was eventually superseded by Scott, handling the camera himself for much of the filming. “I’ve operated on 2,500 commercials, from Morocco to Hong Kong to wherever,” Scott recalled. “On cranes, dollies, handheld and all that. I operated all of The Duellists, all of Alien, all of Legend—I wasn’t allowed to on Blade Runner. You’re painting when you’re operating. The proscenium, which is the viewfinder, is where the bells go off. If you’re the actor, I’m actually engaging with you, I’m looking right inside you, and I’m seeing every goddamn blink. They like that. It’s a bit like being a good still photographer. And then they blossom. They blossom.” With the amount of cameras Scott uses at any one time on a feature now (this Director goes up to 11, Spinal Tap fans!) Scott must restrict himself to multiple monitors and audio instructions to his DoPs.

Film director Kevin Reynolds is a major fan of the film, discussing the film with Scott in an extra Duelling Directors on the DVD/Blu Ray. He enjoys the lead actors portrayals, and spoke of them in a piece in The Telegraph. “There is a temptation in period dramas for the actors to become remote from what they are doing, simply because the clothes, language and some of the attitudes are so different from those of today,” he says. “There is a tendency to overplay or lapse into unnatural gesturing. I suppose you could call it camp. But Carradine and Keitel avoid all that. They move and speak and make what they are doing seem utterly natural and comfortable. They are like real people, almost contemporary people, and after all human behaviour hasn’t changed that much in 200 years or so. They feel genuine, and because of that you can suspend your disbelief and allow the sense of danger and jeopardy to creep in. The Duellists does feel real, and there is a great deal of jeopardy and tension built into each of the conflicts, which is what I hoped to emulate in my picture (2002’s The Count of Monte Cristo).”

The Duellists, in turn, is itself heavily influenced by Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, in its sumptuous photography, exacting detail in costume and settings, and painterly eye; the use of light and particularly its dropping off into blackness (“like Caravaggio” as Scott states). It is not slavish in this emulation though; while Barry Lyndon advances with the forward momentum of one of Napoleon’s columns in its telling of a fool’s misfortune and slow glide towards the destruction of all he worked for and holds dear, The Duellists dashes pell-mell between the very different clashes of the antagonists. It is more earthy, and naturalistic. A special mention should also be made for the superb romantic, melancholy score by Howard Blake. Scott storyboarded the entire film himself, and the delay in filming until the winter was a boon for mood and atmosphere. The low light and rain better suit the melancholy and mortality pervading the piece.

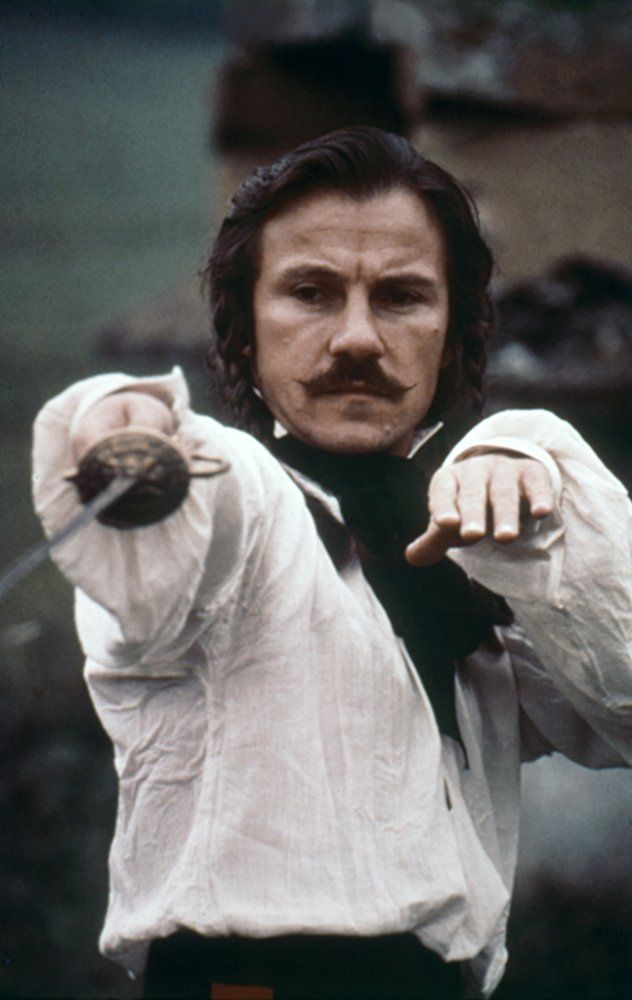

BAFTA-nominated costume designer Tom Rand, who also had a start at the BBC, most likely where he first met Scott, was very particular about the uniforms. “We decided to choose the most contrasting colors of two different regiments, the first to illustrate the cool aristocratic character of one man (Armand/ Carradine), the second to show the hot-blooded temperament of the other (Feraud/ Keitel).” The duels themselves are all stand-out dramatic action sequences, accurately orchestrated by Bill Hobbs. Carradine was already trained in sword fighting, but Keitel was not. He would often lose himself in the moment and step outside his marks, forcing Carradine to improvise. In one drag down, brutal sabre fight, a sunken basement pierced by shafts of magic hour light evokes a similar setting for Barry Lyndon’s fateful pistol duel with Lord Bullingdon. Scott only had forty-five minutes of light left to shoot, doing so himself with a hand-held camera, right in amongst the action. The walls were wired with electrically charged chicken mesh, causing the sabres to spark when striking them.

Ridley Scott economically illustrates the “Armageddon,” as Stacy Keach’s narration puts it, of the deadly Russian winter on Napoleon’s army, where once again war is reduced to, this time, an interrupted matter of personal business. Cossacks are seen off by the duellists. As in Stanley Kubrick’s unmade Napoleon, where Tsar Alexander I weeps by the roadside after the battle of Austerlitz, a frozen soldier here also illustrates the cost of war.

Like Barry Lyndon, interior shots are sometimes composed like still life paintings. In contented silence, Armand and his pregnant wife Adele sit between open fire and window, the camera slowly tracking in. The actors make no movement for several seconds until Adele jumps as the baby kicks and she reaches for Armand’s hand to feel.

The final duel is superbly staged amidst ruins in the early morning misty forest around Armand’s estate, symbolic of Napoleon’s shattered dreams. Each man is armed with two pistols, crisscrossing the screen at different levels, peeking around moss strewn corners and behind trees. Unable to finish off Armand with his final shot, Feraud must finally bow to his fate held in his opponent’s hand (“In all of your dealings with me, you’ll do me the courtesy to conduct yourself as a dead man. I have submitted to your notions of honor long enough. You will now submit to mine.”).

Armand’s voice over here plays as Feraud climbs to a bluff overlooking a flooded valley below, rain clouds sweeping the sky. He wears a bicorn hat and long overcoat like his beloved Emperor. As he stands reflecting on his magnificent obsession and its ruinous conclusion, the vista is reminiscent of a famous painting, Napoleon at St Helena. Serendipity struck here, as in the middle of shooting, the sun peeked from beneath the rain curtain, and slowly continued to edge out. Scott’s camera moves in for a close up of Keitel’s reflective face, before pulling back and around, catching the sun’s rays. While we see the light, Feraud sees only the clouds gloom he is himself garbed in.

Tim Pelan was born in 1968, the year of ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ (possibly his favorite film), ‘Planet of the Apes,’ ‘The Night of the Living Dead’ and ‘Barbarella.’ That also made him the perfect age for when ‘Star Wars’ came out. Some would say this explains a lot. Read more »

DUELLING DIRECTORS: RIDLEY SCOTT & KEVIN REYNOLDS

Duelling Directors: Ridley Scott & Kevin Reynolds (2002)—Ridley Scott and Kevin Reynolds talk about the film. Reynolds interviews Scott while watching the movie, and they examine some of the key visual shots that Scott created and that eventually got him recognized as one of the best visual directors of our time.

Scott based The Duellists on a Joseph Conrad short story, which was based on actual historical events. In this video, StoryDive breaks down those events and the bizarre relationship of the real “d’Hubert” and “Feraud,” who were in truth named Pierre Dupont and François Fournier-Sarlovèze.

2018 BAFTA Fellowship recipient Ridley Scott talks making his way from directing commercials to sci-fi classics like Alien and Blade Runner.

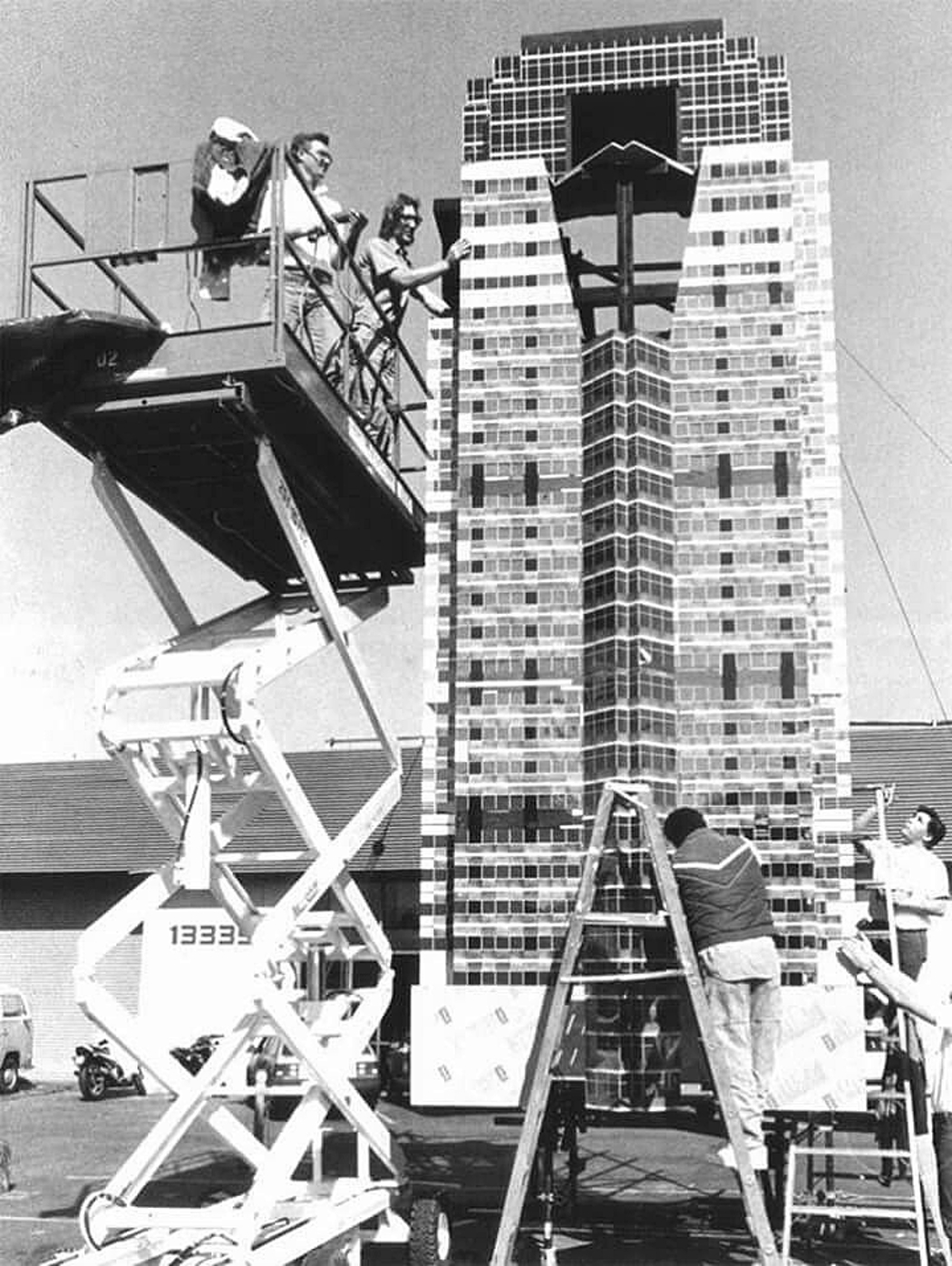

Here are several photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of Ridley Scott’s The Duellists. Photographed by David Appleby © Paramount Pictures, Enigma Productions, Scott Free Enterprises. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or donate directly below: