By Sven Mikulec

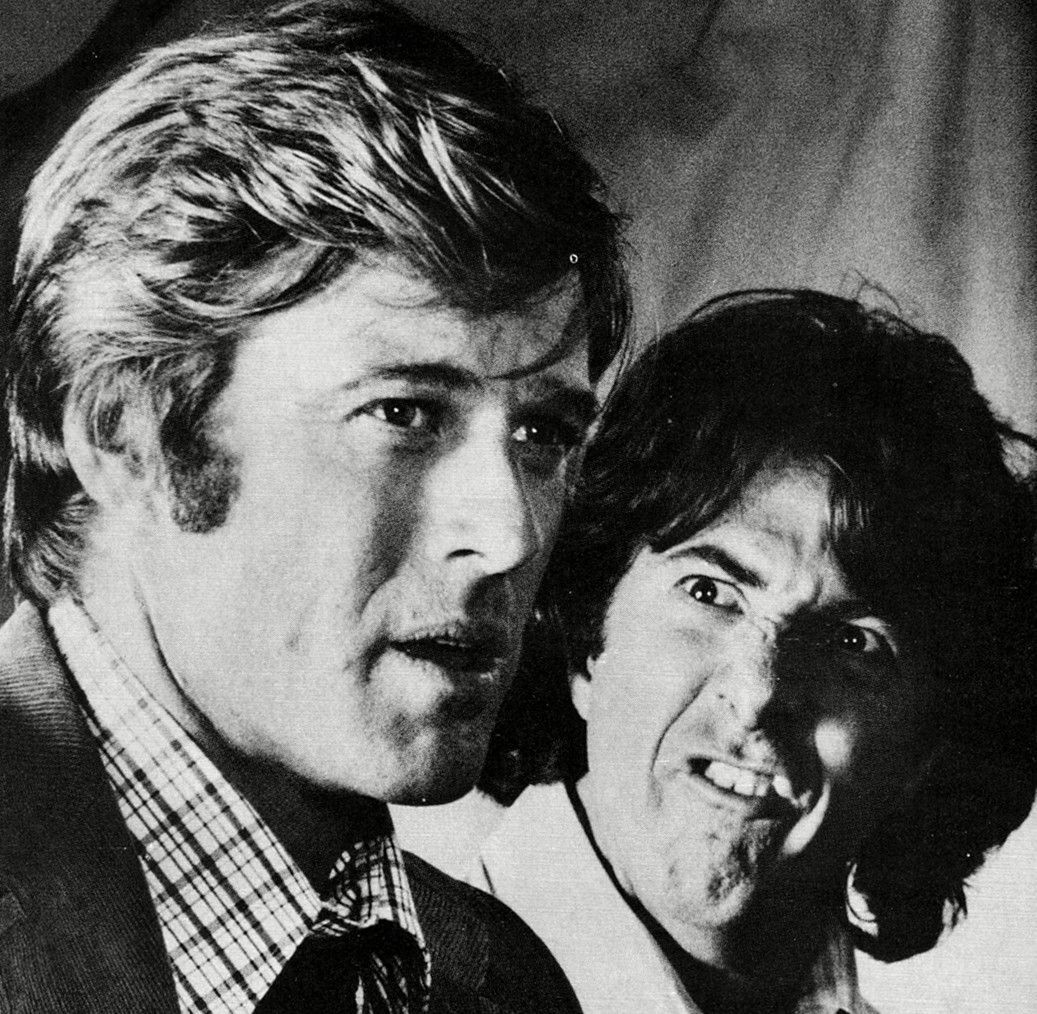

When Robert Redford thought of an idea to make a film about the dogged efforts of two Washington Post reporters working relentlessly to uncover the truth about the Watergate scandal, he envisioned a small, low budget movie with two anonymous actors. Upon contacting Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, he was first ignored, then rejected, only to be approached cautiously and timidly, eventually leading to the green light he needed from the heroes of his story. Even though Woodward and Bernstein were initially skeptical about, how they framed it, “going Hollywood,” the appeal of such a project was simply too high. But when their book ‘All the President’s Men’ became a bestseller in 1974, Redford’s vision was bound to change. A small movie was no longer an option, and Redford bought the rights to the material for almost a half of a million dollars. But it was not an easy point in time to make this film. The Watergate scars were still fresh, only a year having passed since Nixon’s resignation, but the audience was fed up with this story, eagerly waiting to move on with their lives. Redford had a tough time convincing the studios that his project was worth investing into, and only after much deliberation Warner Bros. was on board. It was hardly the case that they had full confidence in the film, but the resourceful star threw in William Goldman, Alan J. Pakula and Dustin Hoffman into the mix, softening Warner’s guard and enabling them to see the potential of this seemingly mistimed procedural thriller, with “no bad guys, no women and no guns.”

William Goldman, the acclaimed novelist and screenwriter who received an Oscar for Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, his first collaboration with Redford, agreed to pen the script. His first draft, however, wasn’t looked favorably upon neither by Redford nor Woodward and Bernstein. The latter, joining forces with his girlfriend at the time, Nora Ephron, wrote his own draft, deeply offending Goldman. Using some elements from the Bernstein version and enhancing Goldman’s original text, Redford allegedly worked hard with filmmaker Alan J. Pakula, his pick for the director’s chair, on producing a new, filmable draft. All of these combined efforts brought Goldman another of the Academy’s golden statues, but the whole experience of making All the President’s Men was not a very pleasant one for the screenwriter. The film, on the other hand, turned out to be a huge financial success, a critics’ favorite and a picture of far-reaching influence and significance. Without Pakula’s vision, it’s more than likely that this wouldn’t be possible. The director was confident that a documentaristic approach to the material, envisioned by Redford, would be a huge mistake. There’s a balance between truth and Hollywood grandeur that needed to be reached if All the President’s Men was to captivate the viewers, he thought. With two big movie stars of the seventies’ cinema working on the picture, why would anyone in their right mind want to discard the two aces from their winning hand? Pakula believed in this precise mixture of fact and fiction, because the audience knew the facts, the scandal hovering around the covers of virtually all magazines for months. What was needed was a cinematic story adhering to the truth, yes, but a story that would, every step of the way, radiate with the qualities only a monumental Hollywood film could produce, stirring emotion and capturing the imagination of millions.

Gordon Willis, the cinematographer who brought us the unforgettable image of Deep Throat lighting a cigarette immersed in the darkness of a public garage, and David Shire, the composer of a spare but perfectly fit score, supplied their talents, with Redford and Hoffman delivering inspired performances in the process. All the President’s Men became a film about journalism so aptly made that all future cinematic enterprises on this particular subject would be measured against it. Last month we celebrated the 40th anniversary of the film’s release, and the fact that there were literally no films of the genre to match it in the decades that passed is indicative of its power. A slow, detailed procedural thriller that unearthed the enormous effort put into leading the investigation that dethroned Nixon is a movie where all the elements fit together, a collective effort that, against odds and expectations from both the contemporary filmgoers and reluctant studio heads, found its way into history books.

A monumentally important screenplay. Screenwriter must-read: William Goldman’s screenplay for All the President’s Men [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

WILLIAM GOLDMAN

John Cleese interviews William Goldman, screenwriter of All the President’s Men, Marathon Man, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Princess Bride, Misery. From the BBC Radio show Chain Reaction, first broadcast on BBC Radio 5 in 1991. “I don’t like my writing,” says legendary writer William Goldman, responsible for a vast body of work encompassing novels, screenplays, short stories, and much else. It is a free-form interview, intimate and engaging, in which Goldman, guided by Cleese, explores various aspects of his large body of work.

William Goldman talks about screenwriting and his own past, another brilliant interview.

Legendary screenwriter William Goldman on his book, Which Lie Did I Tell? Adventures in the Screen Trade.

THE WOODWARD AND BERNSTEIN’S WATERGATE PAPERS

Charged with writing what was essentially a detective story for an audience that already knew “who done it,” Academy Award winning screenwriter William Goldman struggled to condense a 336-page book into a feature length movie. Through several successive drafts, Goldman and actor-producer Robert Redford relied on Woodward and Bernstein’s input to focus the story and accurately recreate settings and events. Goldman’s screenplay eventually won an Academy Award for best adaptation. Woodward, Bernstein, and many at The Washington Post were leery about how they would be portrayed in a movie. In the book, the focus of ‘All the President’s Men’ was mainly on their pursuit of the Watergate story, but on screen there would be much more exposure of individual personalities and actions. These concerns were somewhat alleviated by Robert Redford’s desire for Woodward and Bernstein to help flesh out their characters and scenes beyond the text of the screenplay. Check out the images, courtesy of Harry Ransom Center.

‘ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN’: AN ORAL HISTORY

Forty years ago this month, the premiere of All the President’s Men upended DC’s notion of celebrity. Here, the story behind the making of the movie that brought Tinseltown gloss to Washington proceduralism and transformed Beltway scribes from ink-stained tradesmen to the pinnacle of cool. —All the President’s Men: An Oral History

As Bill Goldman said, “Nobody knows anything. Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for a certainty what’s going to work.” As I recall we only previewed All the President’s Men once, out of state. The audience didn’t know what it was getting. The title was met with silence and scattered boos. The silence held. A few people walked out muttering about a smear job. More silence. I was struck with how abstract the story was. The enemies were just names, their crime was writing checks. Our boys had nothing personal at stake. I leaned in to Pakula. “This is an intellectual picture,” I said. “I know,” he said. “Don’t tell anybody.” And then the picture had its first light moment and the whole room laughed. Silence had meant immersion. So we had them. —Notes on the making of All the President’s Men

PRESSURE AND THE PRESS:

THE MAKING OF ‘ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN’

Running about 10 minutes long, the short, titled Pressure And The Press, features interviews with not only Pakula, Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman themselves, but the real-life Woodward and Bernstein too. Topics covered include the origins of the film, the recounting of the journalists’ real life journey into why Deep Throat did what he did, and what the purpose of the great overheard shot in the Library of Congress was. —Cain Rodriguez, The Playlist

GORDON WILLIS, ASC

Gordon Willis, ASC, had a seismic influence on his chosen art form. One of a handful of cinematographers whose work came to define the American New Wave of the 1970s, Willis became renowned for his inventive visuals in The Godfather, Klute, Manhattan, The Parallax View, All the President’s Men and Annie Hall, among other titles. He earned two Academy Award nominations, for Zelig and The Godfather Part III, and was awarded an honorary Oscar in 2009. In the fall of 2006, Globe reporter Mark Feeney talked with Willis at his Falmouth home about his life and work. Here is a transcript of his conversation with the acclaimed cinematographer. Great interviewee, great interviewer, one brilliant interview all around.

Would you call yourself a perfectionist?

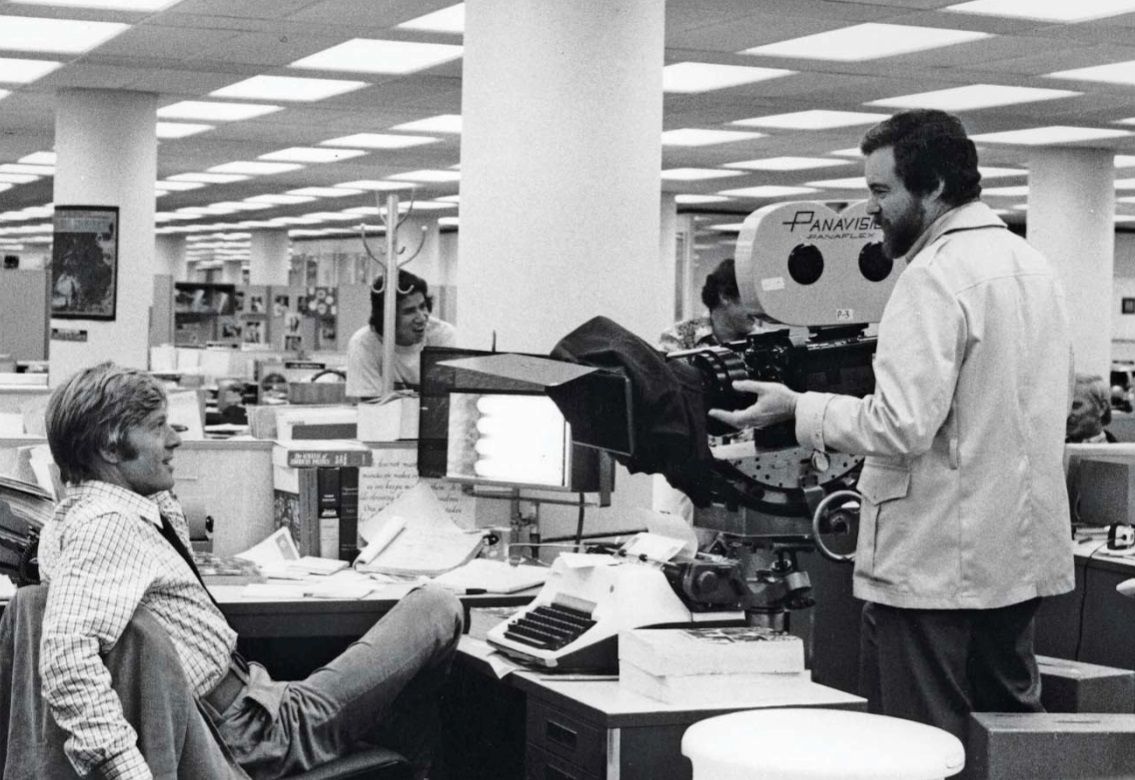

Um. Yes, but I’ve learned to be this kind of perfectionist. After a while perfection becomes a state of mind. It’s not that you’re getting it better. You take a ruler, you draw a straight line. Well, take the ruler away, the line is straight, dammit. You can keep drawing, you can keep looking at it. So the secret to being a perfectionist, at least in the motion picture business, is start off with the appropriate intentions. Know how to do that. And when you get it, be able to recognize it. Don’t keep pushing past it. The Italians have a saying, “Better is the enemy of good,” which is true. No, it doesn’t have to be better. Better for what? So I’ve learned to recognize I can’t do any more. “It’s not great. It’s 20 after four. It does the job. Get the cut.” I see the cut later, I’m not happy, but I knew how it had to be done and for what reason. So you still have to recognize when it’s okay. When you get to that point of trying to get something perfect you’re doing too much. What you should be doing is taking things out, not putting things in. There’s always too much shit on the set, too much stuff on the table. It’s always too much, too much. I’ve probably rubbed more art directors and dressers the wrong way by taking stuff away or minimizing something. You learn to design things for time, and sometimes you make the right decision and sometimes you make the wrong decision. But you have to make those decisions.So it’s not always an aesthetic decision. Sometimes something has to be happening in a day or 20 minutes or something. I’ve looked at things I thought were pretty good at the time and though, “Nah, this is not any good.” I’ll never forget, I finished shooting Klute, which was my first movie for Alan. I was so sick of shooting it, because it was hard to shoot, with a lot of problems by the time I was finished with it. We were having dinner with Helen, my wife, and Michael Chapman [Willis’s cameraman on the film], and his wife, and I said, “I hate this [obscenity] thing.” Helen said, “This is a good movie.” I said, “Really?” [chuckles] So sure enough, she was right. You know, I went back and I looked at it a long time ago and it’s a very good movie. It’s very stylish. I did really, really good work a couple of times there. I enjoyed it. So don’t get making the movie mixed up with the movie. I was so sick of it I perceived it as bad. Yeah, I go in and out on things. President’s Men, that’s another thing. They did a 25-year thing, a re-release, of President’s Men on DVD. In it is me and Redford and other people discussing the movie. I looked at the movie again, and I’m very proud of that movie because it’s a stylish movie where the appropriate decisions were made. There’s no tour de force. It’s extremely difficult to keep delivering information on every cut. You want to kill yourself after a while, you know. Every cut you had to deliver information. There’s only one really tour de force shot in it.

The Library of Congress.

Yes, exactly. So I said [to Pakula], “Well, you know what we’re doing here.” “Yeah, I know, but I think it’s important,” Alan said. So, okay. We did it twice because we didn’t have any video then. So I had to figure it out on paper. But it worked fine. The movie was very well put together. It really is.The acting, the minimalist music, the look of it—there’s a level of professionalism to that movie that is unthinkable for Hollywood now.

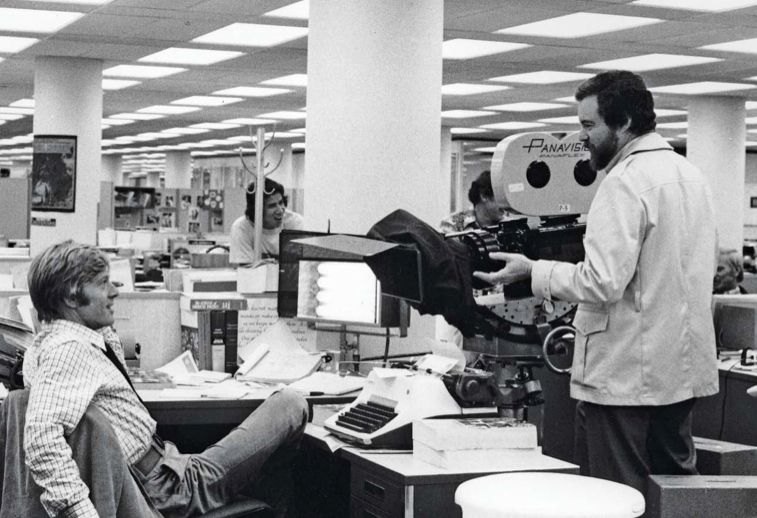

No, they can’t do it. And that’s what you have to do when you choose how to shoot a movie. You got to keep your eye on the ball. This is what you have to keep doing because this is the right way to do it. You have to stay on track. So I’m very proud of it. As I said, delivering information every cut, yecch. And working in that newsroom for weeks and weeks and weeks was beginning to get to me.Now you know what it’s like to be a journalist.

That’s right. I said that to those [Washington Post] guys, “How the hell do you work in this place?” At any rate, we made those decisions. The basic discussion we had on the look of the film was that what we wanted was poster art, and that gives good relativity. I like going from light to dark, dark to light, big to small, small to big, and good and evil. So if you took those ideas and used them in a graphic way you’d make the right choices. I thought it was very good. You go from that [newsroom] to Deep Throat [in a parking garage]. And Deep Throat I kept in that same creepy color but in a different [visual] structure. But wherever you went, still going back to this poster-art look. There was never a shot list in the script. The way it worked, at least with me, with directors is: You rehearse the scene on the set, you make a quick decision about it. I’m partial to playing certain scenes in long shots. I think there’s a lot of drama in a little person in a lot of space. And sometimes it can be a lot more moving and/or a lot scarier if you see something, see somebody, framed up that way. I think the relativity of going from a cut like that, to a cut close on somebody’s face, or even leaving that area in the long shot and going to a closer cut, while they’re in bed, for instance, that works. So I’d rather see the soprano die of tuberculosis in a long shot, for instance, than 29 close-ups of her going cough, cough, cough. I don’t think it works so well, although people still love to shoot it that way. —Gordon Willis

THE UNMAKING OF A PRESIDENT

Few films have affected the way Americans think about the presidency as profoundly as Alan J. Pakula’s All the President’s Men. In a 1976 story in the DGA’s Action magazine, Pakula talked about the experience of directing it.

My idea was to start the picture with no camera movement—just people sitting at telephones doing their work. Then the camera starts to move as the people become more manic, the action becomes more intense. Finally, at the end I did the longest move of the picture, a race by Redford and Hoffman the complete length of the newsroom. In a picture with so many words there is a tendency to over-use the camera. I tried not to. —Alan J. Pakula

All the President’s Men Revisited—Robert Redford’s Primetime Emmy-nominated behind-the-scenes and historical documentary. Also starring Dustin Hoffman plus the real Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, Ben Bradlee, John Dean and more.

Alan Pakula: Going for Truth encompasses the personal and professional life of Alan J. Pakula, a lauded filmmaker and extremely private man, who was unflinching in his commitment to bringing some of the most memorable movies of the last half of the 20th century to the big screen. Always placing story first and going for truth, with anonymity being his preferred style of directing, this elusive artist finally gets his spotlight. Select cast and crew members from his wide ranging filmography including To Kill A Mockingbird, Klute, All the President’s Men, Sophie’s Choice, Presumed Innocent, and The Pelican Brief bring Pakula to life once more after he was lost so tragically; while family and friends share their memories of knowing him as an artist, a husband, and a stepfather.

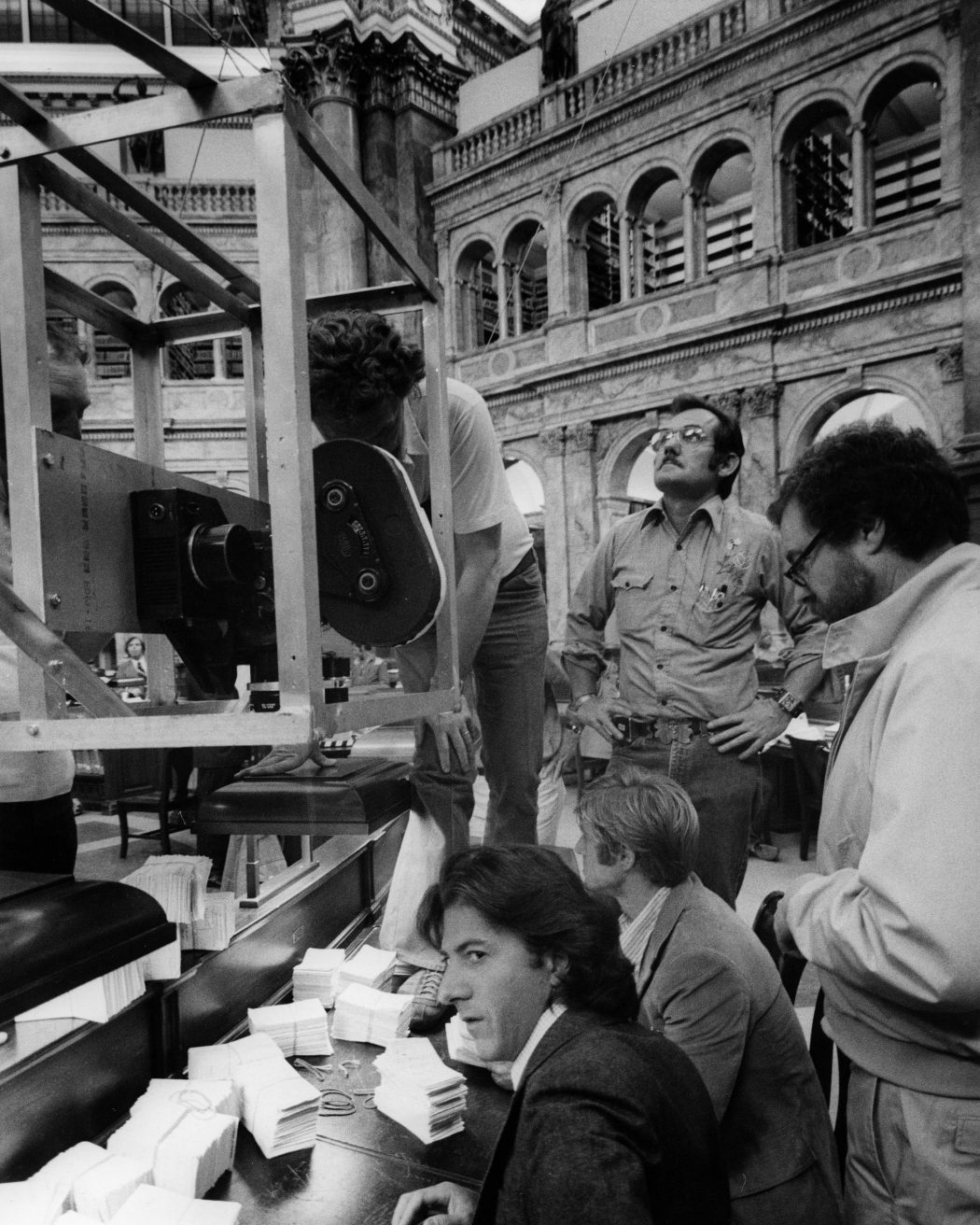

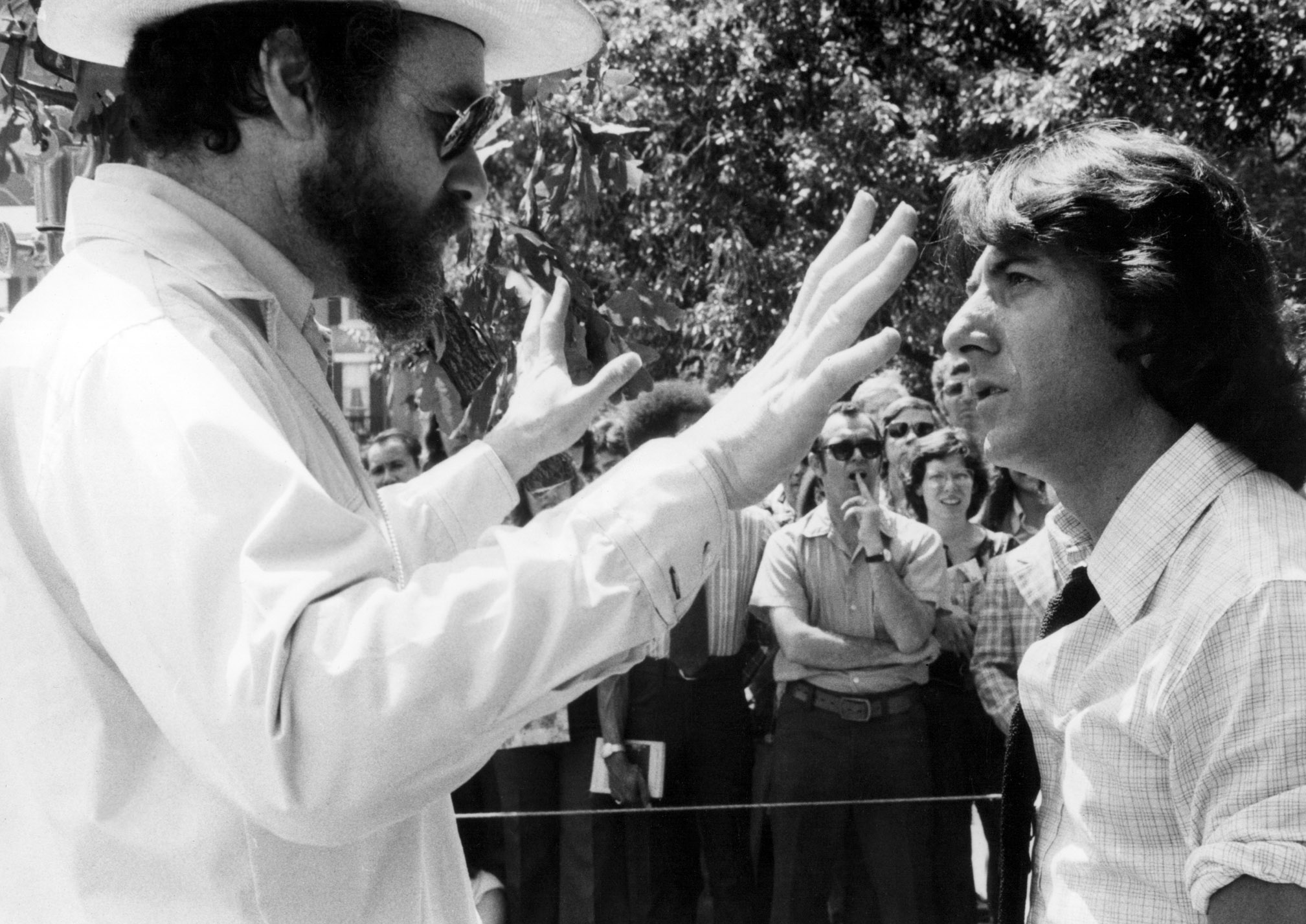

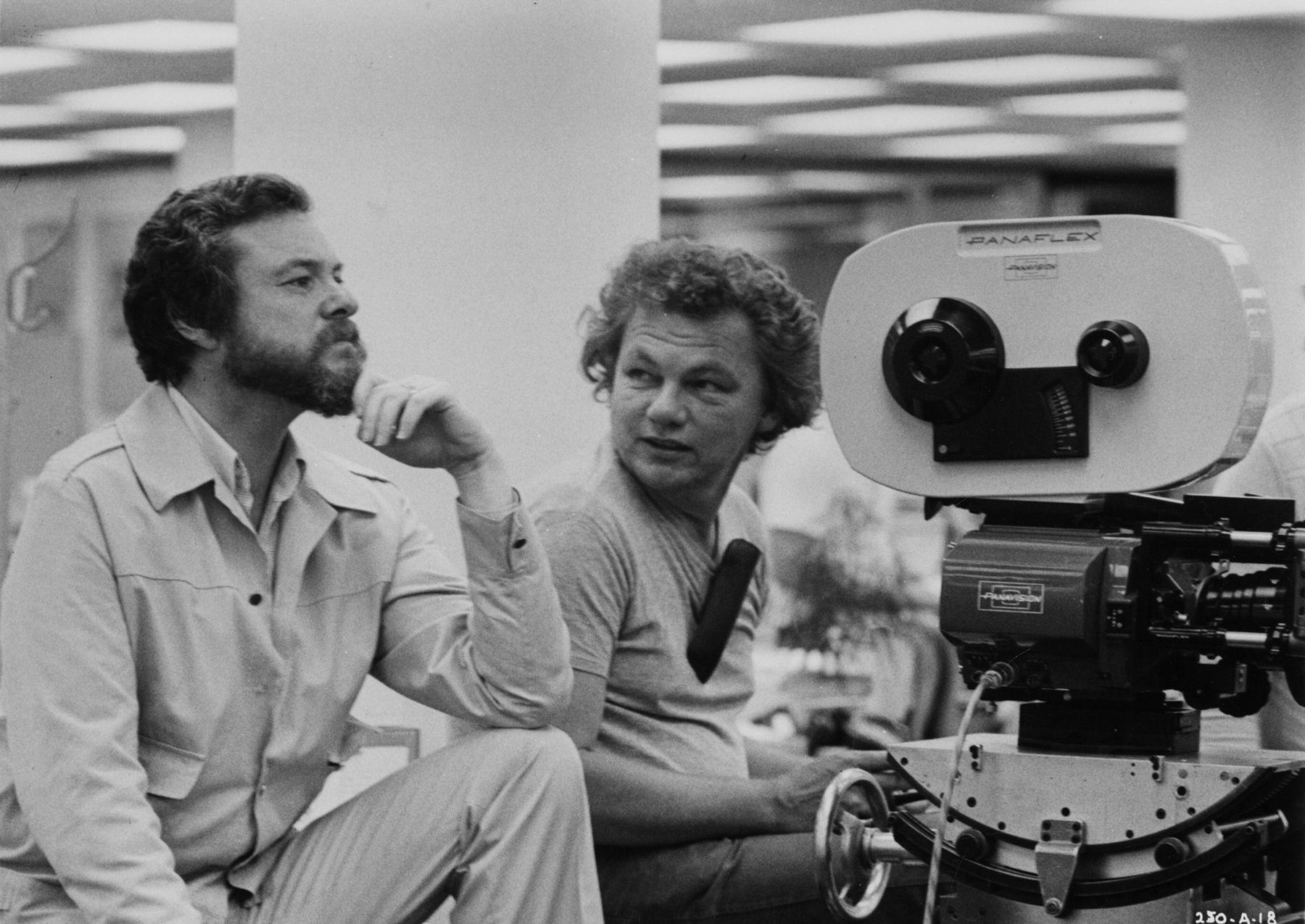

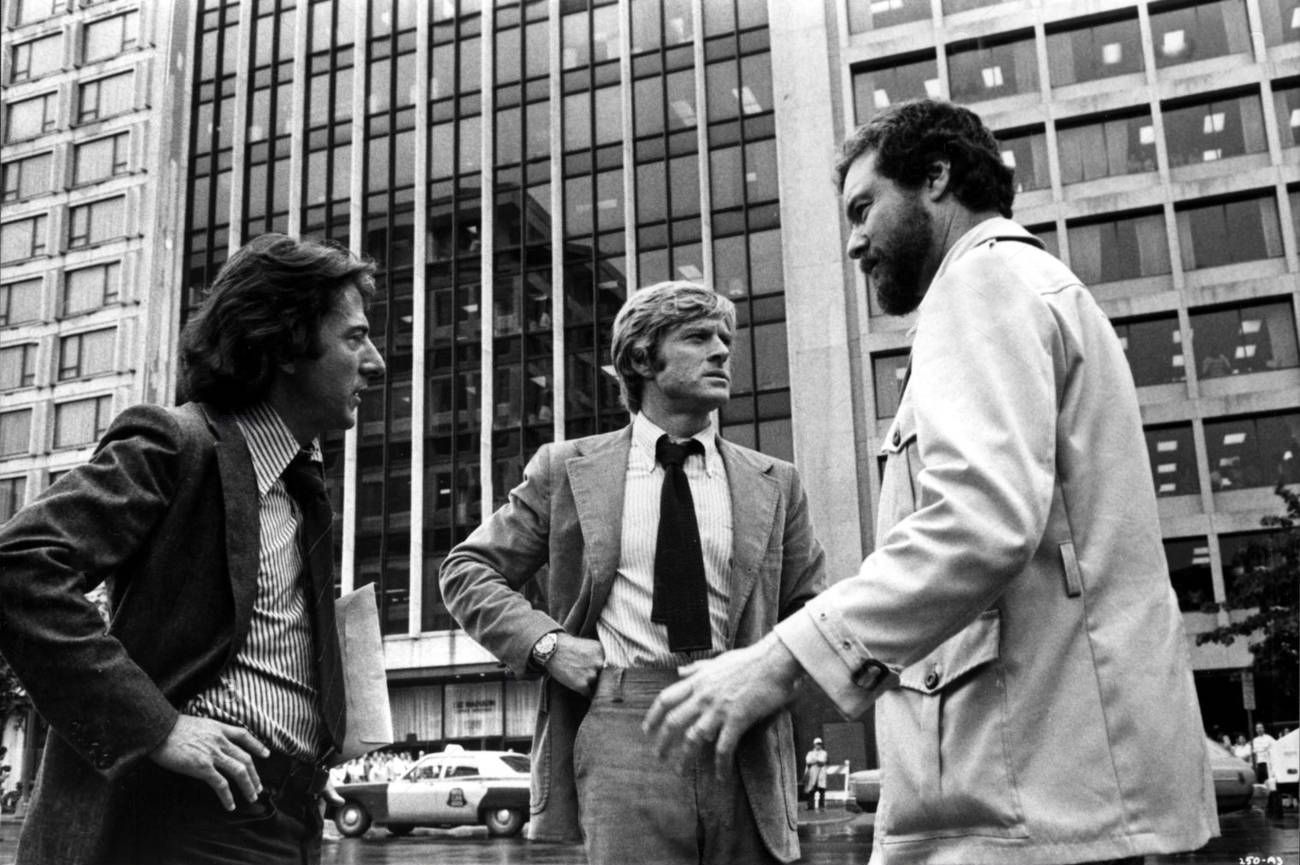

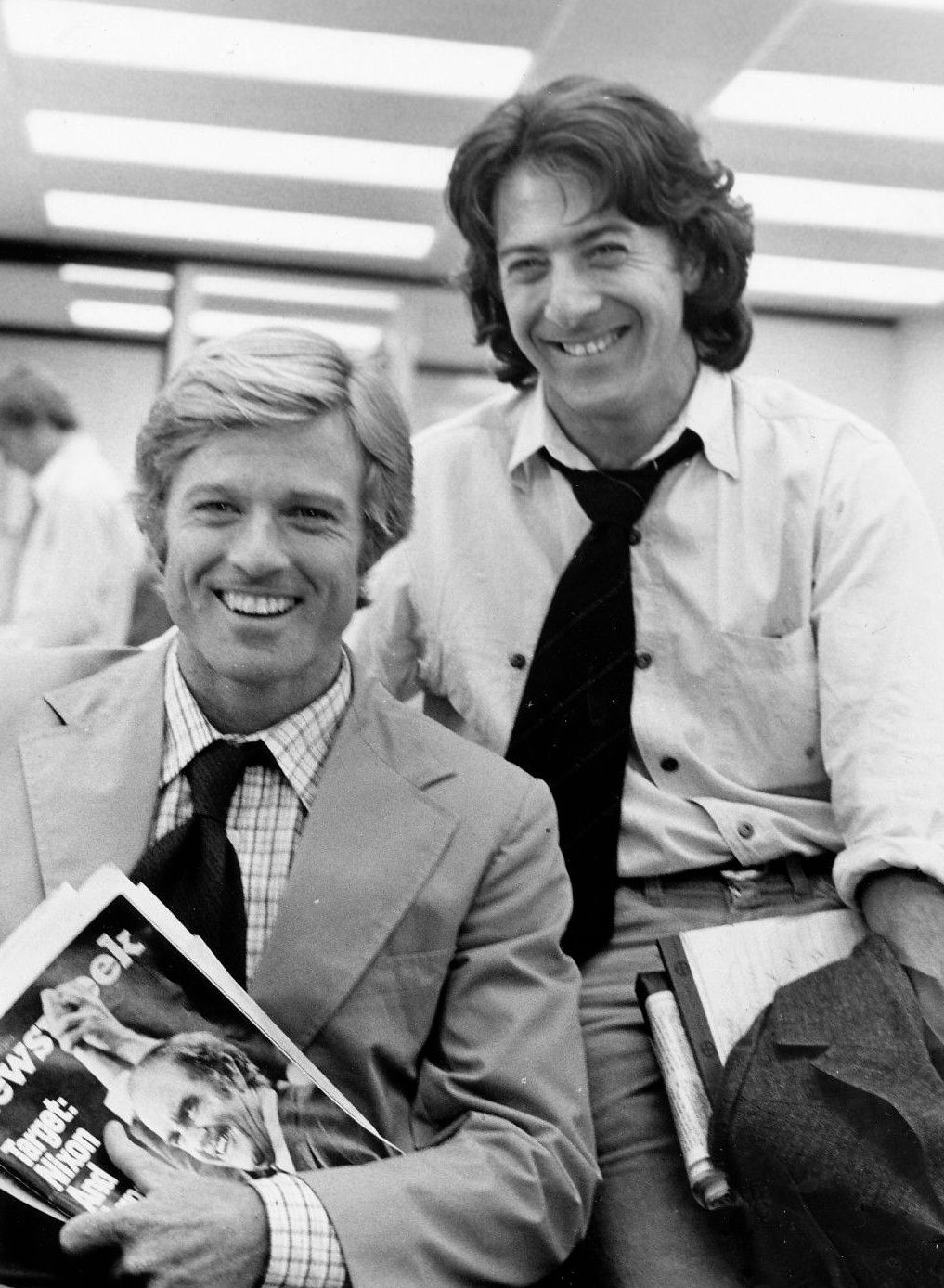

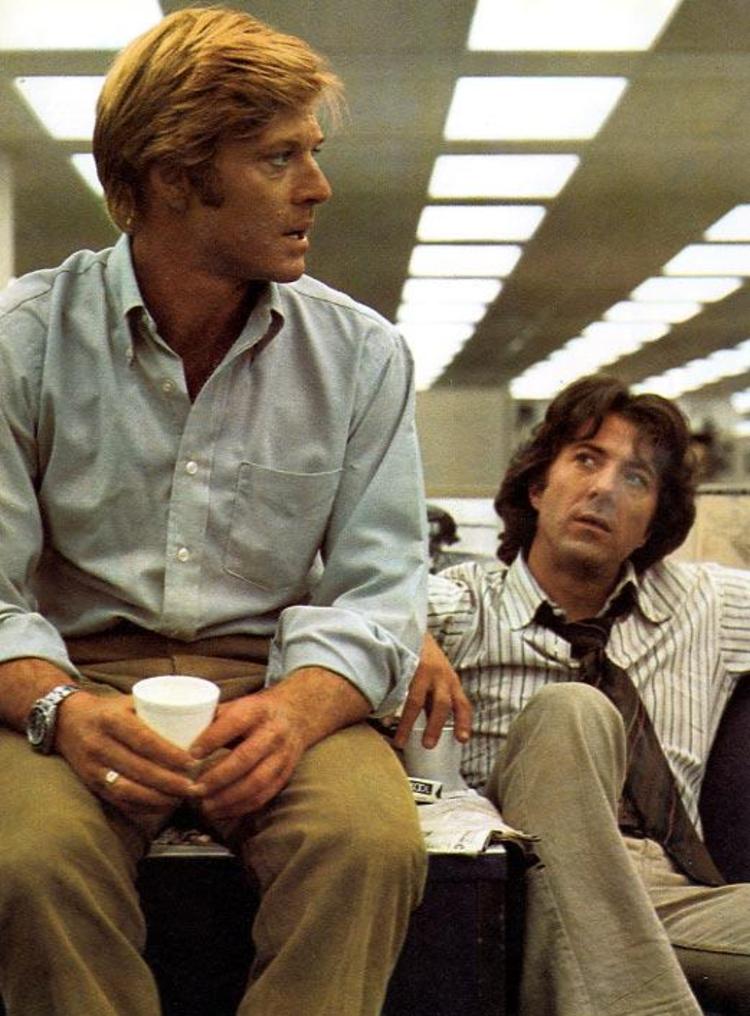

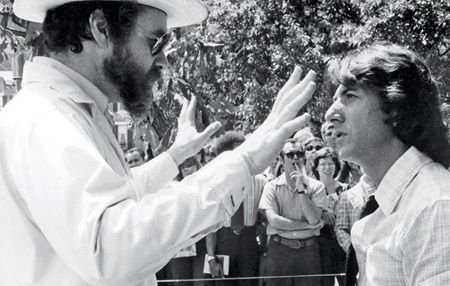

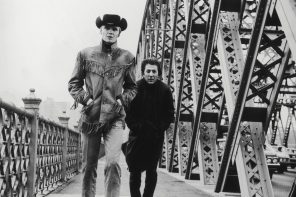

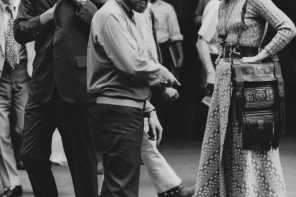

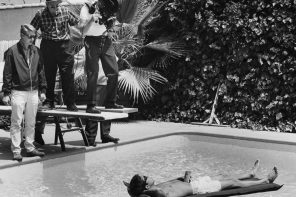

Here are several photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of Alan J. Pakula’s All the President’s Men. Photographed by Howard Bingham & Louis Goldman © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., Ronald Grant Archive, American Cinematographer. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

We’re running out of money and patience with being underfunded. If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or donate directly below:

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in

[newsletter]