By Sven Mikulec

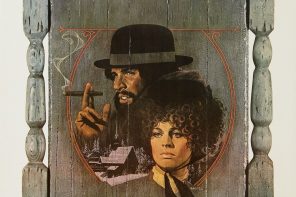

The seventies were a unique period in the history of the United States, with general dissatisfaction with the government and distrust of the system generously fueled by Nixon’s Watergate fiasco that led the American people to question their belief system and reinvent their unsettled, if not shattered identities. This particular feeling among the people of America unavoidably influenced the contemporary cinema, bringing life to memorable film characters written as individuals dedicated to their work and upholding certain moral thresholds that forced them to battle the system. One of such characters was newspaper reporter Joe Frady, a man who singlehandedly decides to expose the sinister assassin-recruiting secret corporation in Alan J. Pakula’s cult thriller called The Parallax View. The middle part of Pakula’s political paranoia trilogy, alongside Klute and All the President’s Men, The Parallax View is a mesmerizing thriller marked by the exceptional performance of Warren Beatty, but also by its ability to create tension, paranoia and instill distrust in the viewers. “If the picture works, the audience will trust the person next to them a little less,” Pakula allegedly told Beatty, and it’s easy to deduce the mission was a success. The film capitalized on the growing emotions of the American society and, what perhaps we find most interesting, succeeded in telling one of the most powerful JFK stories without even touching upon the subject of the president’s assassination. Instead, The Parallax View chooses to focus on the efficient and cloaked mechanism of producing “lone gunman” patsies, at the same time observing the eluding nature of conspiracies and making a sharp comment on the dehumanizing aspect of modern-day high-profile corporations.

This particular aspect was neatly created with the help of Gordon Willis, definitely one of the leading cinematographers of the decade, who worked on such movies as The Godfather, The Godfather: Part II, Annie Hall, Manhattan and All the President’s Men. “The Prince of Darkness,” as he was called because of his inclination to use shadows and the dark to full effect, developed the film’s unique visual identity, with several unforgettable sequences and designs that put forward the feeling of the alienating, entrapping nature of stern architecture with lots of empty spaces. Based on American novelist Loren Adelson Singer’s novel of the same name, the screenplay, on the other hand, was credited to Lorenzo Semple Jr. and David Giler, who was called to do some last-minute rewrites, but the script was a much bigger problem than these simple credits suggest. Due to a writer’s strike and Beatty’s busy schedule, the film was supposed to go into production without a finished screenplay. It was Pakula and Beatty, with the help of Robert Towne, that polished it and enabled the start of production. Edited by John W. Wheeler, with Michael Small’s score persistently playing with the audience’s expectations and against the on-screen events, The Parallax View premiered in July, 1974, with its reputation steadily growing in the years that followed. Today, Pakula’s film is credited to be one of the ultimate conspiracy theory thrillers of all time, fascinating in its evocation of the general atmosphere of post-JFK, post-Watergate, post-compliant America.

A monumentally important screenplay. Screenwriter must-read: David Giler, Lorenzo Semple Jr. & Robert Towne’s screenplay for The Parallax View [PDF]. (NOTE: For educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available from the Criterion Collection. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

In his two-and-a-half hour archive interview, Lorenzo Semple, Jr. outlines his successful career in feature films with such movies as Papillion, The Parallax View and Three Days of the Condor, as well as the cult classics Pretty Poison and Flash Gordon. Lee Goldberg conducted the interview on September 25, 2008 in Los Angeles, CA.

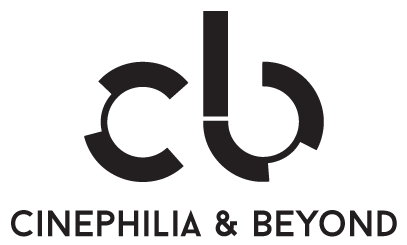

GORDON WILLIS, ASC

Gordon Willis, ASC, had a seismic influence on his chosen art form. One of a handful of cinematographers whose work came to define the American New Wave of the 1970s, Willis became renowned for his inventive visuals in The Godfather, Klute, Manhattan, The Parallax View, All the President’s Men and Annie Hall, among other titles. He earned two Academy Award nominations, for Zelig and The Godfather Part III, and was awarded an honorary Oscar in 2009. In the fall of 2006, Globe reporter Mark Feeney talked with Willis at his Falmouth home about his life and work. Here is a transcript of his conversation with the acclaimed cinematographer. Great interviewee, great interviewer, one brilliant interview all around.

“The directors I’ve worked with have all been really nice people, and they’ve always allowed me to do what I’ve wanted to do visually. I might add that what I want to do is based on what the director is trying to accomplish, but I’ve never had problems with directors telling me how to light or which lenses to use. In general, they’ve just discussed the concept and what they’re trying to achieve. Of course, one doesn’t always agree on how something should be shot—whether a scene should be close, wide, moving, et cetera. That type of discussion can be touchy. Whatever you suggest should improve or embellish the director’s design. Also, you should never express your dislike for an approach without being ready to offer an alternative that you feel can make an improvement.” —Gordon Willis, ASC: Supervising a Set

“Pakula had told his cinematographer that he wanted a comic book look, which Gordon interpreted as composed flat and frontal, with bold blocks of carefully calibrated color. Mainly, Gordon struggled with the fact that Parallex was a ‘damn jump cut picture.’ Since they didn’t have a script yet, the picture he was shooting, he knew, would be cuisinarted into a whole new story. This betrayed his visceral need to shape the visual whole. He cursed when we shot entrances and exits to establish a scene: these were ‘just damn shoe leather’ that would slow down the picture and confuse things. He swore that it would all end up on the floor. Inevitably, he said, the movie would jump from the middle of one scene to the middle of another. So that was how he held it all together. He photographed his close-up shots from exactly the same distance, scene after scene in the picture, and used exactly the same focal length lens. That way, Pakula could jump from scene to scene by going from one close-up to another, and the picture would still feel solidly constructed.” —A Remembrance: Jon Boorstin’s Parallax View on Gordon Willis

A brilliant, often controversial cinematographer shares his considerable expertise with student filmmakers of the American Film Institute. This interview was originally published in American Cinematographer, September 1978.

“For the most part, such things are planned. It’s like picking focal lengths to shoot with. There are a lot of machine-gun shooters in the business right now, which is a shame. They just arbitrarily cut close-ups with a zoom lens. For example, let’s suppose I shoot a close-up of an actor at 150mm. Then I turn around to shoot the matching close-up of another actor, only to find that, because of the physical limits of the location, I can’t get far enough away to shoot him at 150mm. I end up shooting his close-up at 50mm—and you’re forced to do that occasionally—but I’ll do anything to avoid it, because when you cut those two close-ups together the backgrounds won’t match, the perspectives won’t match, and the feeling won’t be the same.” —Gordon Willis, ASC Interview at AFI

In one eight-year period, he photographed—among others—Klute, The Godfather, The Paper Chase, The Parallax View, The Godfather Part Two, All the President’s Men, Annie Hall, Interiors, and Manhattan. His influence will never wane; there simply isn’t anyone who’s any good who isn’t standing on his shoulders. Steven Soderbergh interviewed him for a documentary he made about Gordon Willis’ first feature, End of the Road.

It’s surprising to me sometimes how a very theatrical stylistic choice can actually feel very real. I’m thinking about Parallax, when he’s in his little room, when Warren Beatty’s in his room, pretending to be the guy, and Walter McGuinn comes and—

Yeah, in the door? Yeah, right——when you go into a tableau, it’s pretty–you’re further away than any wall that was in that space—

Right.—in theory. But I noticed, in trying to break down how it was done, it’s seamless when you watch it, you don’t ever think—

No.—that wall would be 20 feet from there.

Right. You don’t think about it.

No, because that’s where you want to be. It feels right.

Exactly. If you go too far, though, it doesn’t work. [laugh]Your relationship with Pakula must have been pretty fluid.

It was very fluid. To be honest, most of the people that hired me after a certain point were people that wanted me to help design their movies structurally. By that I mean visually. And so with Alan it was—we had a good start with Klute… he was very—I understand there could be a lot of deliberation…

Parallax was a lot—yeah, right, a lot of that. President’s Men—he was dreadful with not being able to make up his mind. We’d lay things out and then he’d say, well, what are my options? I said, well, there aren’t any, we have to commit to this idea and go through with it. I said, too many options and six months from now you won’t know what movie you shot here. So he was not good at making up his mind. He was intellectually very fruitful. But he was happiest covered in papers and books. That was his happiest moment. And talking about scenes. I mean, he’d disappear in rehearsals for two hours and you’d wait around with a cup of coffee. He’d say, OK, we have it. And then I’d go into the set and they didn’t have anything. They hadn’t blocked anything, they hadn’t done anything except talk about it. So OK, boom-boom-boom, we’d block and he’d say, oh, that’s very good. Let’s do that. And boom. So that was really the kind of working relationship with Alan, which was pretty good for a while. And then I guess the last movie I shot with him, Devil’s Own, with Harrison, he had actually kind of turned himself over to Harrison at that point, so he became even worse. But he was a very nice man, intellectual, and he was very, very appreciative of good stuff on the screen, very appreciative. Women liked him a lot. Actresses liked him. Men didn’t like him at all. He made male actors very—Just because of that quality—

Yeah, that effete quality made them very—yeah, yeah, they didn’t like him. The women liked him a lot. —Gordon Willis by Steven Soderbergh

In post-Watergate America, folks were scared. Really scared—of wire-tapping, of Communism, of the Cold War still raging, of assassination, and of media manipulation. In Alan J. Pakula’s masterpiece The Parallax View, Warren Beatty’s character is summoned to The Parallax Corporation to test his emotions, his mental acuity, his allegiances. This is the film he is shown. Courtesy of The Parallax Corp.

‘THE PARALLAX VIEW’—FILMS & FILMING REVIEW

“In the 1960s, the United States went through two apocalypses from which it did not emerge as the same country. One was the Vietnam war; the other was the political assassinations of John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King. In the last decade, Hollywood finally started to deal with the Vietnam war, and lately there’s been a plethora of films about it. But although there have been revelations—for example, the Los Angeles Police Department was recently forced in a law suit to open its files on the Robert Kennedy assassination, and it turned out that 2,500 official police photographs and all the physical evidence from the assassination had disappeared—no such attention has been paid to the events that occurred in Dallas, Texas, Los Angeles and Memphis, Tennessee. In the last 25 years or so, the years that have elapsed since the murder of John F. Kennedy, Hollywood has made few films on the subject; they include the docu-drama Executive Action, Winter Kills and The Parallax View, made 16 years ago. Something happened in Dallas in 1963. We don’t know what it was, and nor do the people who made this film. They’re only guessing. That’s all we can do. But something happened, and it changed the world, and we’re living with those changes now.” —Alex Cox’s original introduction, from the first Moviedrome Guide

And below is the introduction from the second broadcast of the film as part of the BBC’s marking of the 30th anniversary of the JFK assassination, on the 21st of November, 1993 at 10:40pm. Courtesy of Moviedromer.

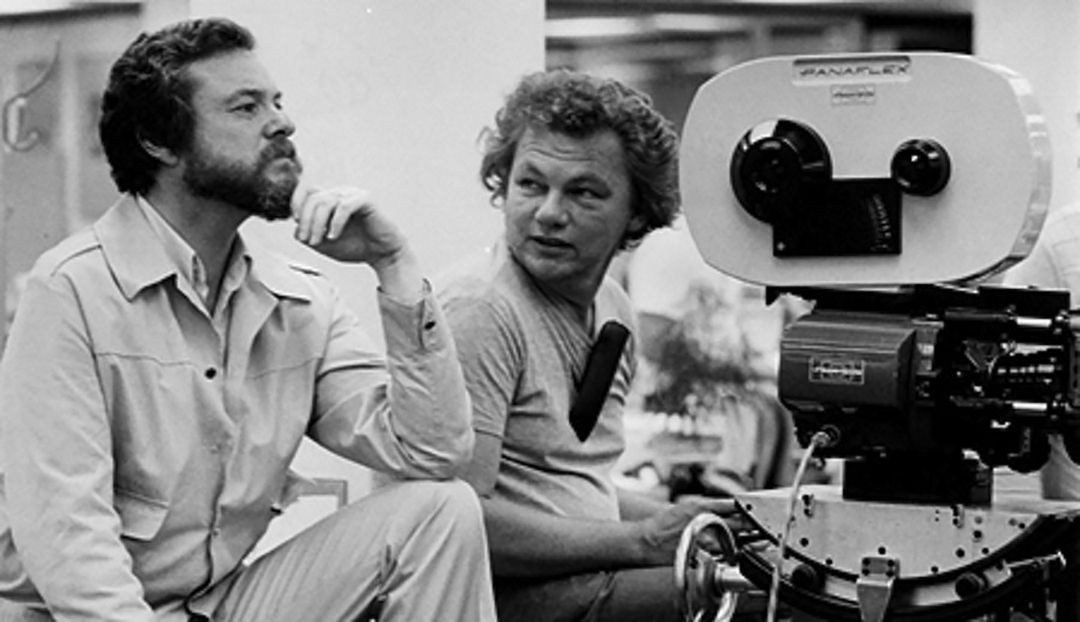

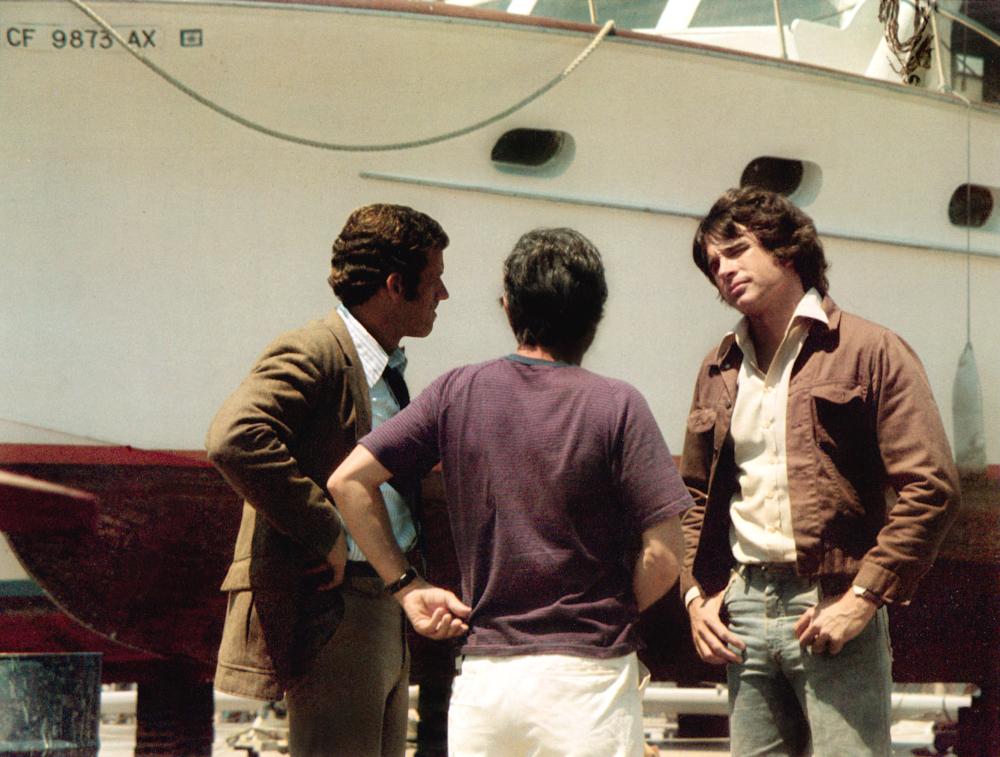

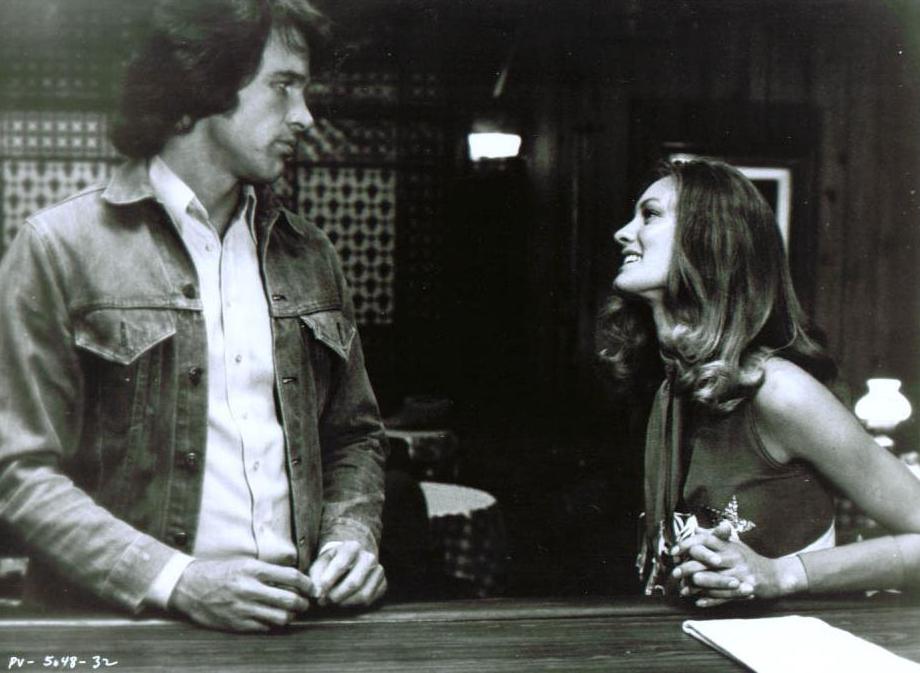

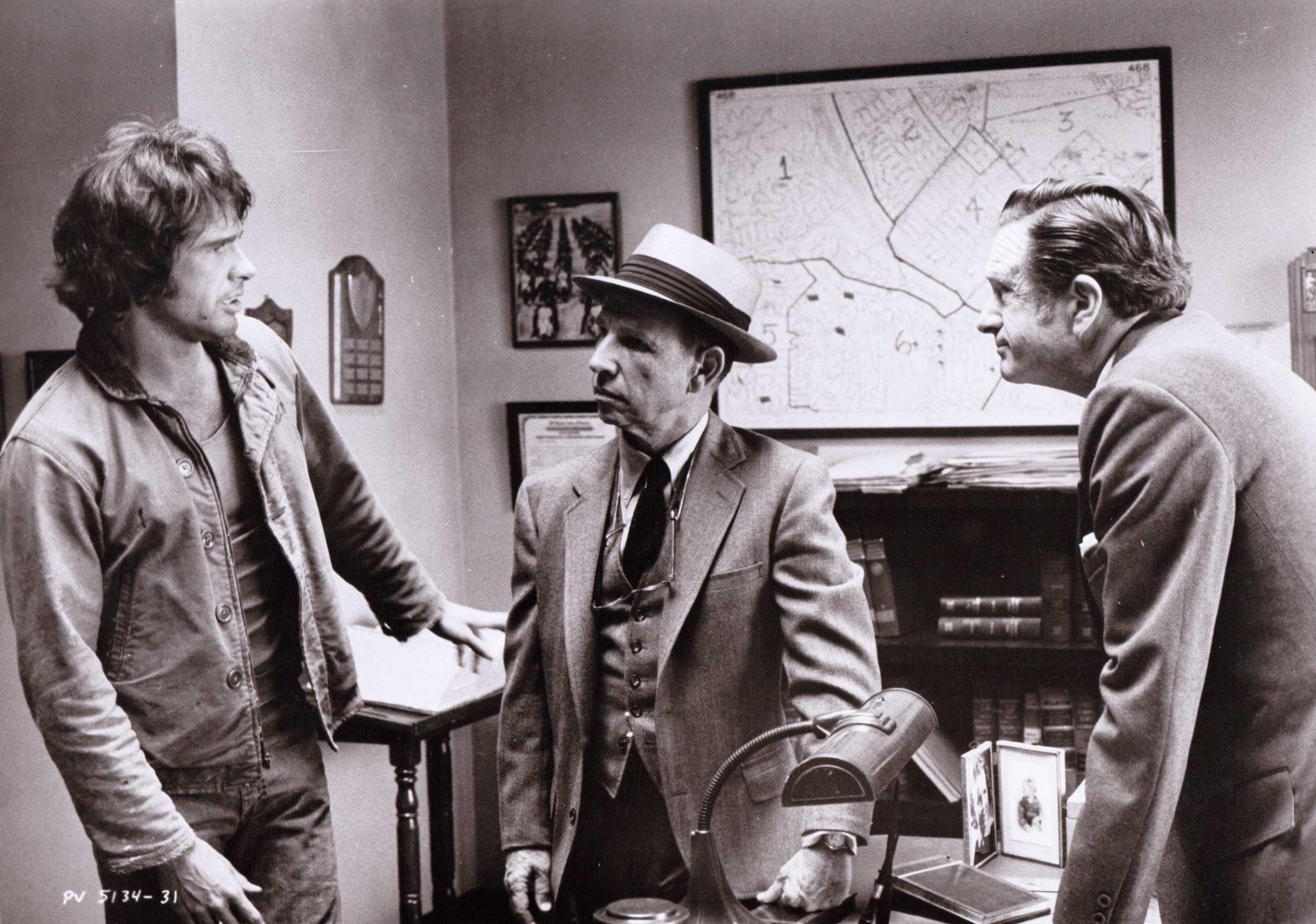

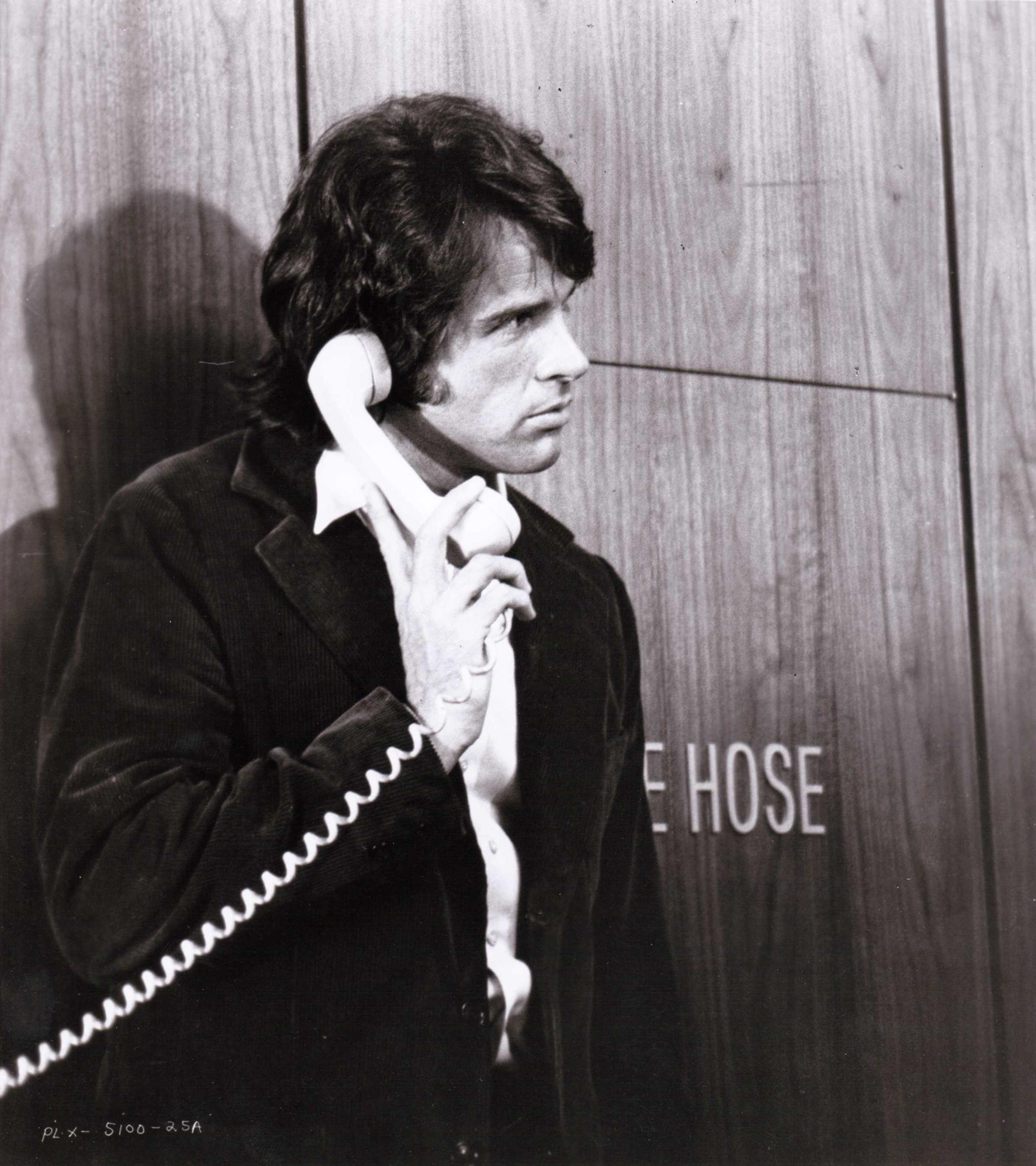

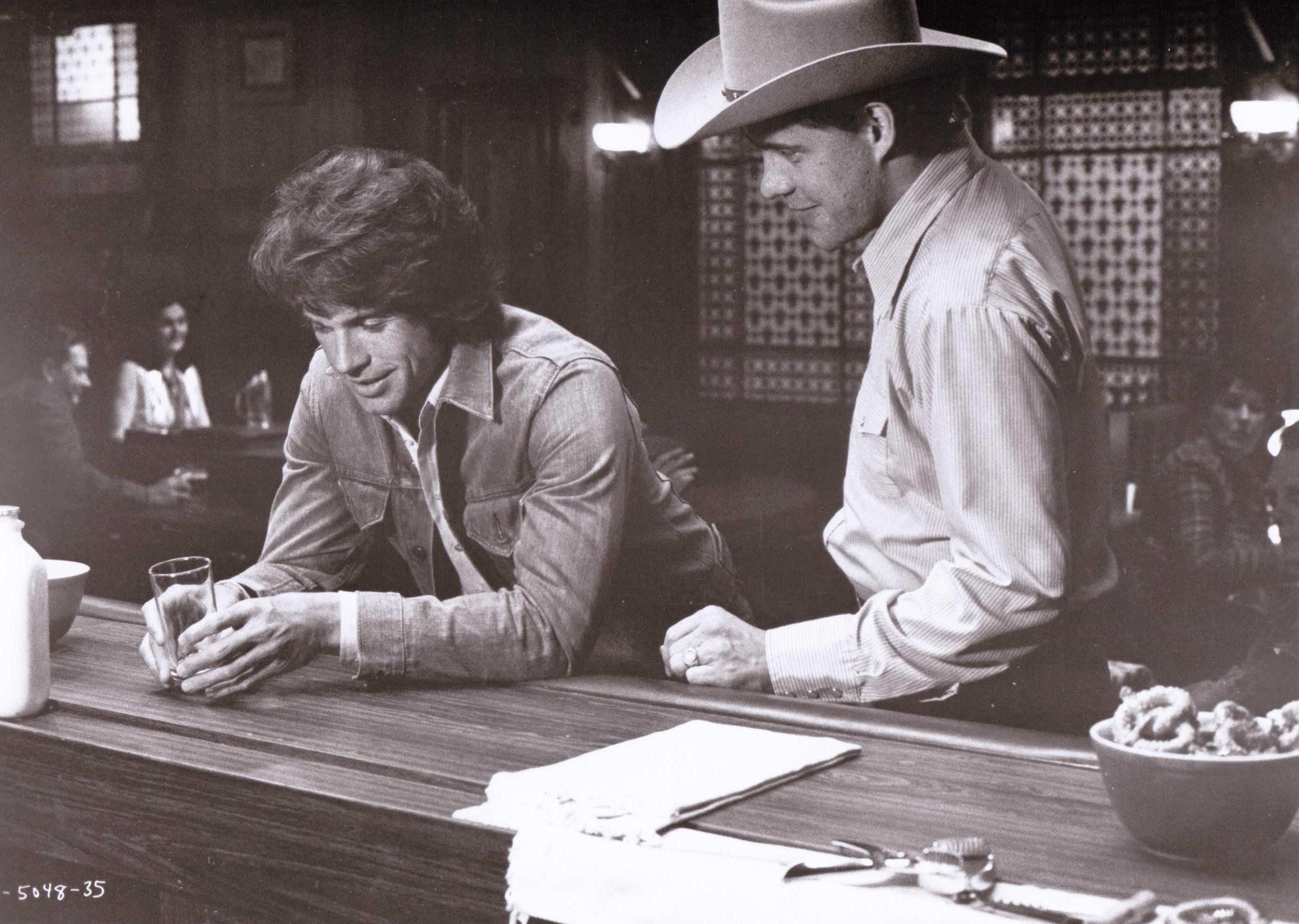

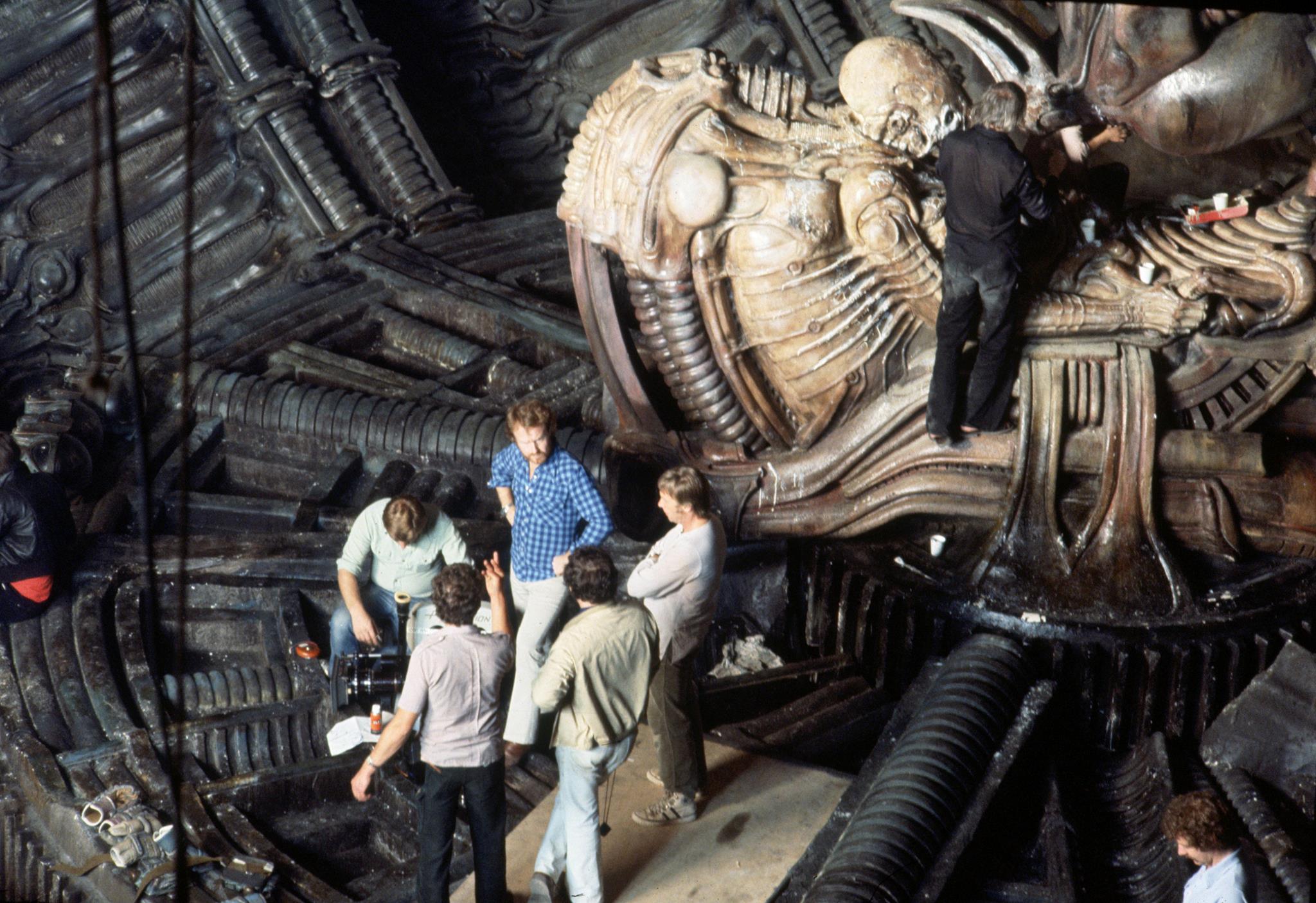

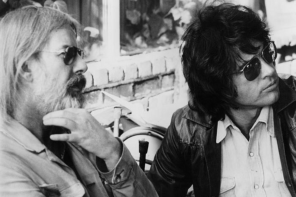

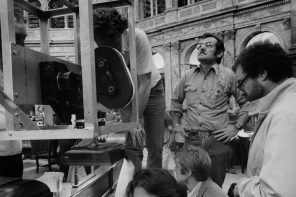

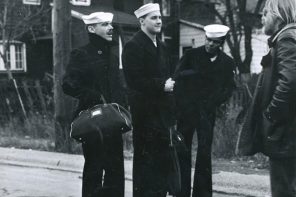

Here are several photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of Alan J. Pakula’s The Parallax View. Photographed by Brian Hamill © Doubleday Productions, Gus, Harbor Productions, Paramount Pictures. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

We’re running out of money and patience with being underfunded. If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or donate directly below:

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in

[newsletter]