By Koraljka Suton

I am not fascinated, as you say, by the myth of the West, or by the myth of the gangster. I am not hypnotized, like everyone east of New York and west of Los Angeles, by the mythical notions of America. I’m talking about the individual, and the endless horizon—El Dorado. I believe that cinema, except in some very rare and outstanding cases, has never done much to incorporate these ideas. And if you think about it, America itself has never made much of an effort in that direction either. But there is no doubt that cinema, unlike political democracy, has done what it can. Just consider ‘Easy Rider,’ ‘Taxi Driver,’ ‘Scarface,’ or ‘Rio Bravo.’ I love the vast spaces of John Ford and the metropolitan claustrophobia of Martin Scorsese, the alternating petals of the American daisy. America speaks like fairies in a fairy tale: “You desire the unconditional, then your wishes are granted. But in a form you will never recognize.” My moviemaking plays games with these parables. I appreciate sociology all right, but I am still enchanted by fables, especially by their dark side. I think, in any case, that my next film won’t be another American fable. But I say that here and I deny it here, too. ‘Once Upon a Time in America’ is my best film, bar none—I swear—and I knew that it would be from the moment I got Harry Gray’s book in my hand. I’m glad I made it, even though during the filming I was as tense as Dick Tracy’s jaw. It always goes like that. Shooting a film is awful, but to have made a movie is delicious. —Sergio Leone

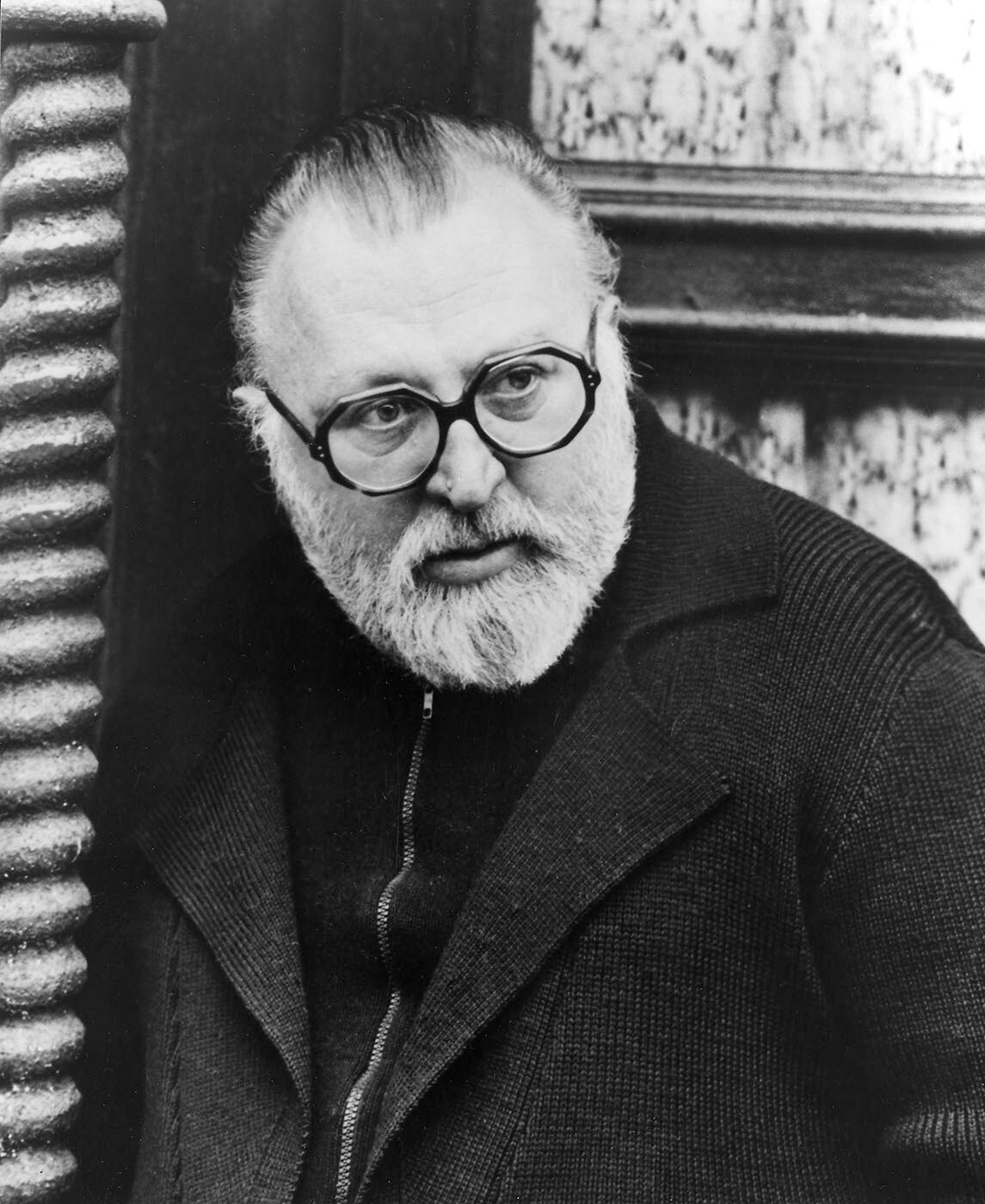

The great Italian director Sergio Leone established himself as the inventor of the spaghetti Western genre in the mid-1960s thanks to his Dollars trilogy (A Fistful of Dollars, For A Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad and the Ugly) starring the legendary Clint Eastwood. His three following and equally adored films would become known as the Once Upon a Time trilogy and would end up spanning three decades—the first installment, called Once Upon a Time in the West, was released in 1968, the second one Duck, You Sucker! came out three years later in 1971, and the last one titled Once Upon a Time in America took him over a decade to make. During the 1960s, the director read the part-memoir, part-fiction novel The Hoods written by Harry Grey, a former Russian-American gangster whose real name was Herschel Goldberg and who, although hesitant at first, agreed to meet with Leone, only because he had seen and liked his Westerns. During their meeting, the director asked the not all too communicative Grey/Goldberg questions about his real-life experiences, to which the author only gave short answers, which was understandable due to his former lifestyle and the inevitable, justifiable paranoia that accompanied it. The two met several more times during the 1960s and 1970s, with Leone intending to understand the author’s perception of America better. Leone became so obsessed with turning the source material into a movie that, when approached by Paramount several years later, he even declined to make The Godfather. Little did the filmmaker know it would take him another ten years to get his passion project made and that it would, regrettably, be his very last one.

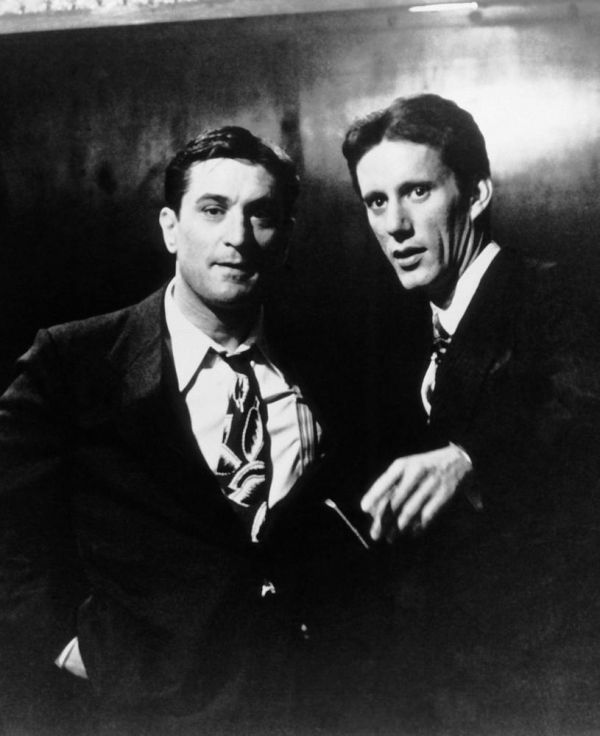

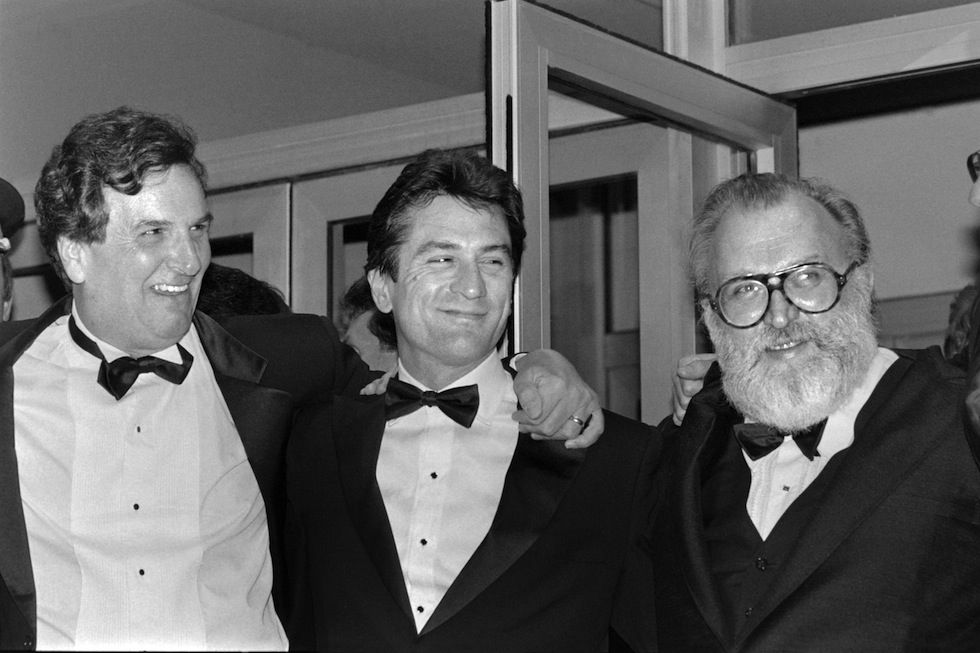

The first draft of the movie was written by American author Norman Mailer, known for the novel The Naked and The Dead and his Marilyn Monroe biography. But the task of making a comprehensible screenplay out of the director’s colossal story turned out not to be an easy one, for Leone remained thoroughly unimpressed, later on telling American Film “I’m sorry to say, he only gave birth to a Mickey Mouse version. Mailer, at least to my eyes, the eyes of an old fan, is not a writer for movies.” The shooting script was ultimately written by Italian screenwriters Leonardo Benvenuti, Piero De Bernardi, Enrico Medioli, Franco Arcalli, Franco Ferrini and Leone himself. The result was a 317-page long screenplay that was finished in 1981, with principal photography beginning on June 14, 1982 and ending on April 22, 1983. Robert De Niro was set to play the lead role, although he reportedly almost declined because the director peed on the toilet seat of the actor’s New York hotel suite, which De Niro interpreted as a power play. Luckily, the producer managed to convince him to take on the role of the protagonist called Noodles. Considered for the role of Noodles’ best friend Max were Harvey Keitel, John Belushi, Dustin Hoffman, John Malkovich and Jon Voight, until James Woods was cast. Brooke Shields was offered to play Noodles’ love interest Deborah Gelly, but the part then went to Elizabeth McGovern, with a young Jennifer Connelly playing her child self.

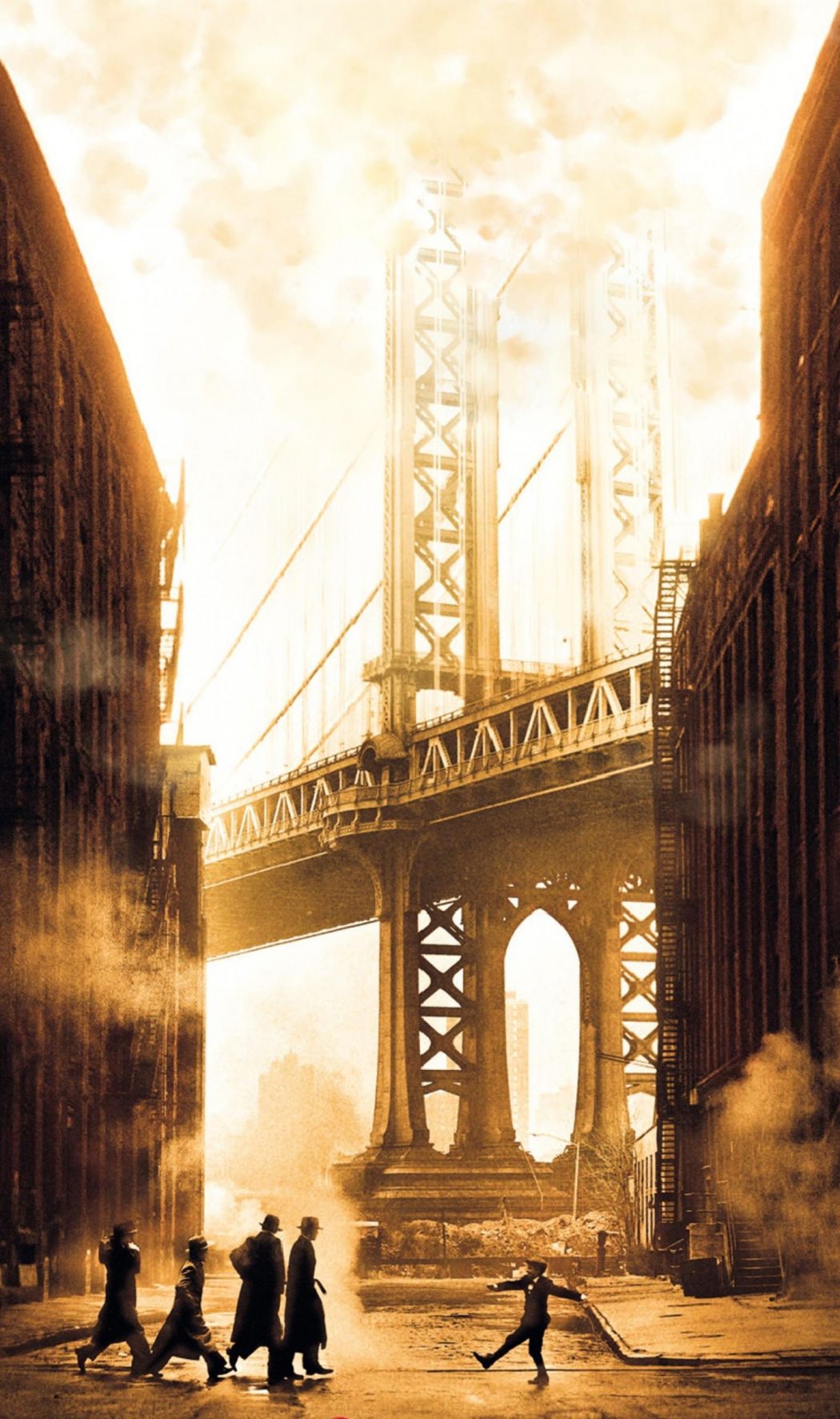

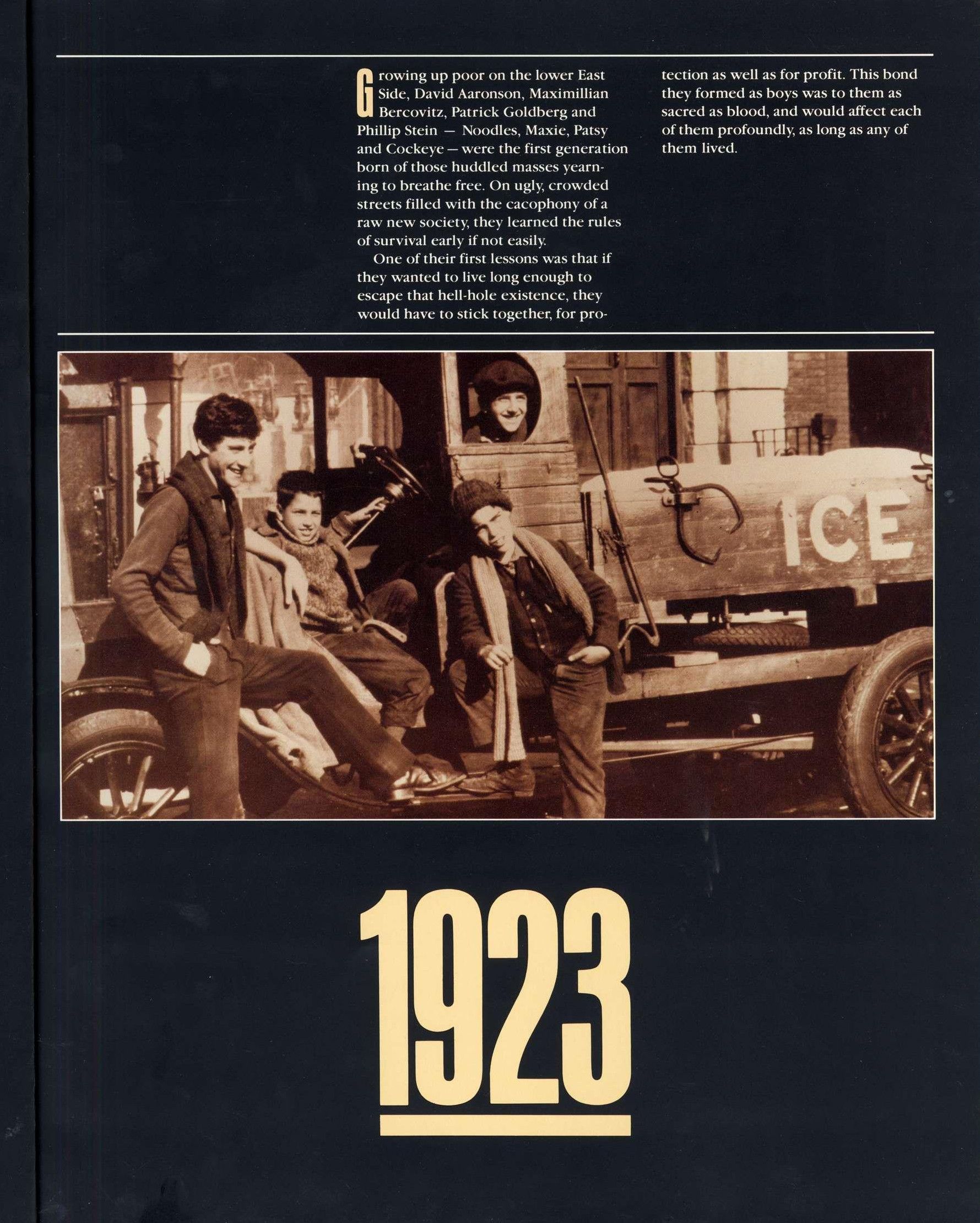

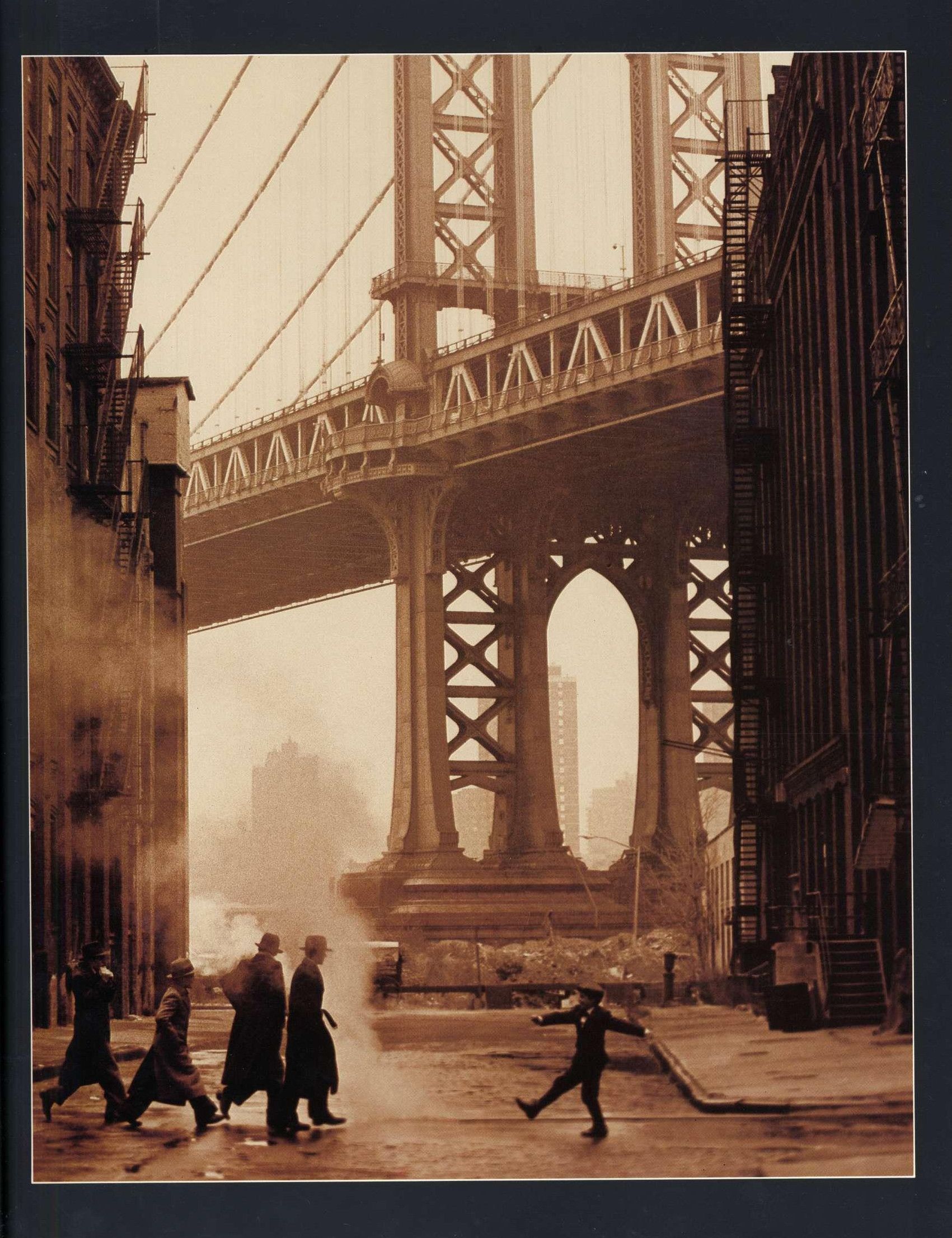

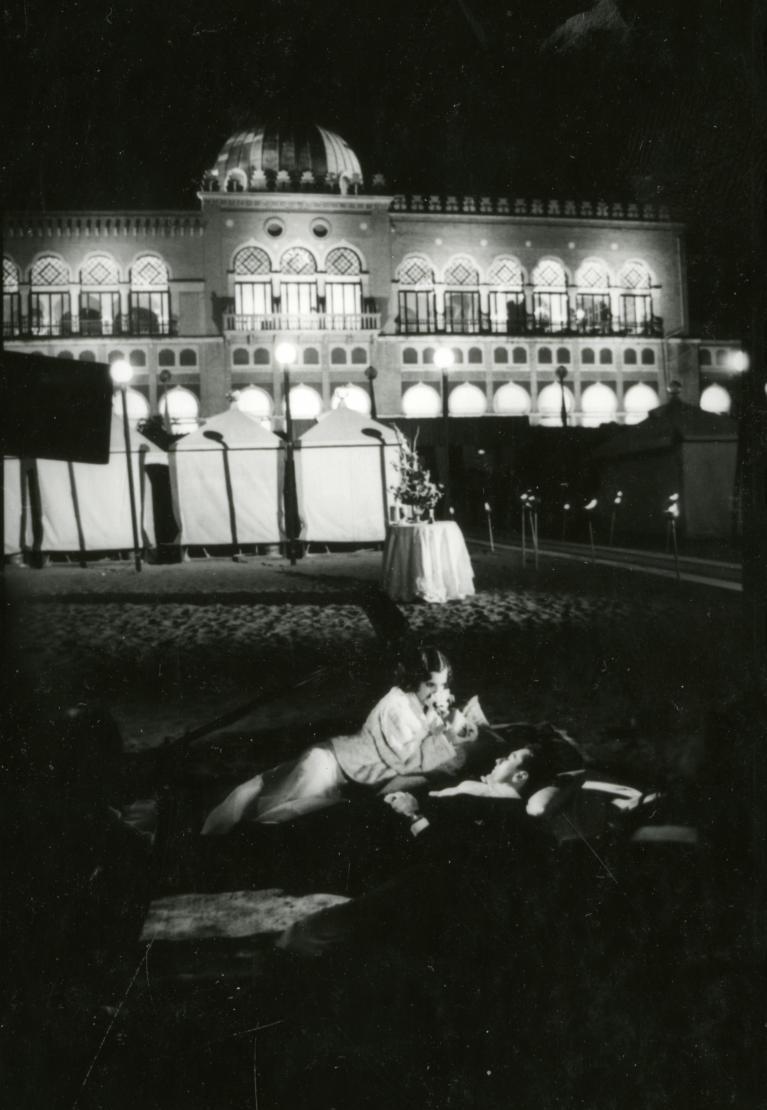

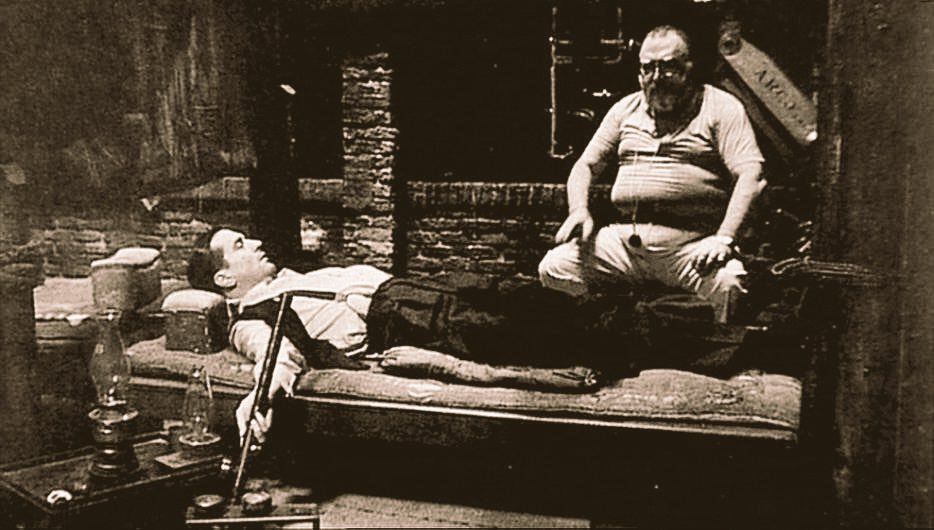

A great portion of the film was shot at the Cinecittà Studios in Rome, and several scenes were filmed in Paris, St. Petersburg, Florida and Montreal. But the parts that were shot in the United States were as authentic as can be—the Jewish neighborhood where a bulk of the story takes place was a street in Brooklyn that had been made to look the way it did in the 1920s. It was on those streets that the main characters of Leone’s movie spent their childhoods, resorting to petty crimes at first, only to progress to more serious ones as time went on. This segment of the characters’ lives is presented to us in flashbacks and is meant to be seen as a collection of the main protagonist’s memories. The first part of the movie sees a grown-up Noodles hiding from hitmen in an opium den and eventually leaving the city. Only after he returns thirty years later are we, the viewers, given extensive glimpses into his childhood and are acquainted with his merry band of misfits that we had thus far only known by name. Leone constantly goes back and forth in time, establishing not only the lives of his characters at different stages, but also three distinguished areas of American history: the poverty of Manhattan’s Jewish ghettos in the 1920s, criminal life during the 1930 Prohibition era and finally the dangerous streets of 1968 New York.

In an interview with Marlaine Glicksman, Leone stated the following about the United States: “America is so varied and exciting that after six months, you go back and find it completely changed. America interests me above all because it is so filled with contradictions, interesting contradictions, which change constantly. Even if you’ve decided that you don’t want to deal with that subject again, before you know it, the desire comes back to do it yet again. (…) The world is in America. In Italy is only Italy. France is full of France. Germany is full of Germany. In a continent that contains the entire world, contradictions are, of course, constantly arising. One of these contradictions that I like to sight is that two of the biggest moneymaking films in America were Mary Poppins and Deep Throat. One, of course, is the opposite of the other. But most likely seen by the same public.”

And Leone depicts this world that is “in America” not just beautifully, but also realistically. For he is first and foremost an artistic genius, dedicated to detailed, intricate and deeply intimate portrayals of lives lived, friendships betrayed and dreams broken. In Once Upon a Time in America, he deals with the illusion of the American Dream, as seen through the eyes of Jewish kids whose entire childhoods are drenched in poverty, with the prospect of crime being the only logical solution, for which there exist no feelings of remorse or guilt. It is a visceral depiction of toxic masculinity which still reigns supreme in today’s world, showing inherently broken children rising to power through violence and corruption. It is also a painfully accurate portrayal of inexcusable misogyny which was once considered a norm, with acts of violence (sexual and otherwise) against women shown in great detail and with little to no restraint. It is also a story of a man who feels inferior to the woman he claims to love, leading him to exercise his dominance the only way he knows how—and resulting in her leaving him behind to make use of her talents and build a respectable life and career for herself.

Once Upon a Time in America is also a narrative about our loyalties to one another, which more often than not lead to us sacrificing our own desires, wants and needs for the sake of life-long friendships that have become such a crucial part of our being, that giving them up would feel akin to dying. It is a story of a man who at one point comes to a forking in the road, but chooses to follow the path of least resistance and continues living the only life he has ever known, until it catches up with him. It is a tale of a human being who ends up exercising his free will and consciously choosing to believe a false narrative, so as to keep his memories intact, his self-concept alive and the life he wasted feeling remorse from crumbling before his very eyes. It is a complex and elaborately nuanced saga about the trajectories of once marginalized and impoverished people, about the guilt that accompanies betrayal, even when it is done for the purest of reasons, about the incessant passing of time that heals no wounds, when the carriers of said wounds are not looking for healing.

Once Upon a Time in America requires the viewer’s full-blown attention and patience, with the camera constantly zooming in and lingering on the actor’s faces so as to convey as much emotional nuance as possible. The pacing is slow, but we do not mind, for it enables us to walk around in the characters’ shoes and experience the passing of time that leaves none of them unburdened. It is, in short, poetry in motion. There is a story the director once told, of an Italian critic who gave his film A Fistful of Dollars a bad review upon its release. “Then he became a fan of mine later. He went to the university here [Rome] with Once Upon a Time in America. We showed it to 10,000 students. And while the man was speaking that day to the students, with me present, he said, “I have to state one thing. When I gave that review about Sergio’s films, I should have taken into account that on Sergio Leone’s passport, there should not be written whether the nationality is Italian or anything else. What should be written is: ‘Nationality: Cinema.’” And Once Upon a Time in America could rightfully be described as pure, unadulterated Cinema with a capital C.

Unfortunately, not many American viewers or critics thought so when the movie hit theaters in the summer of 1984. The reason was the severe injustice done to Leone’s masterpiece by the hands of US distributors. The story goes as follows: at the end of the shoot, the director had eight to ten hours of material on his hands, which he and his editor Nino Baragli managed to cut down to six, with the intention of it being released as two three-hour movies. But his vision seemed to be too grandiose for the producers who, given the critical and commercial failure of Bernardo Bertolucci’s historical drama film 1900 that was released in two parts in 1976, insisted he cut the material some more. After having reduced it to a length of four hours and twenty-nine minutes (269 minutes), the producers were still nowhere near satisfied.

Leone ultimately gave them a 229-minute movie that had its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in 1984 where it received a 15-minute standing ovation, and subsequently played in European theaters. This is the version that European audiences and critics talk about when praising Once Upon a Time in America as one of the greats, a masterclass in storytelling, directing, acting and cinematography. But American audiences were not so lucky, for what they got to see was an even shorter version of Leone’s classic, a 139-minute “travesty,” as Roger Ebert referred to it in his review, where he compares the original he had the chance to watch in Cannes and the butchered version that was presented to the American public. This desecration of Once Upon a Time in America was done without the director’s supervision and against his will, by an assistant editor who had worked on Police Academy. The version in question was not only barely comprehensible, but also ruined the cast and crew’s shots at even getting nominated for the following year’s Academy Awards (the movie did get two Golden Globe nominations though: for Best Director and Best Original Score). To make things even worse, the soundtrack provided by Leone’s frequent collaborator, the incredible Italian composer Ennio Morricone, was disqualified from the Oscar consideration to begin with, because his name was omitted from the opening credits.

Apart from doing Morricone’s haunting score a great disservice, the 139-minute version failed on numerous other levels. In the American cut, Leone’s non-linear storytelling was abandoned for a chronological one, scenes have been extensively left out (the ones depicting Noodles’ childhood in particular), characters that had previously not been introduced suddenly appear on-screen, crucial pieces of information go missing and the relationships between the characters seem unmotivated and unclear. Even the ending, which is considered to be one of the most ambiguous ones in the history of cinema, sparking debate and various theories decades after its original release, has been cut short and turned into a more than obvious, yet somewhat dissatisfying, conclusion. Needless to say, everything that made Once Upon a Time in America truly enchanting was sacrificed and burned at the stake, turning the cut in question into an incomprehensible train wreck severely lacking the magic needed to hold its puzzle pieces together.

The director’s collaborators and peers have frequently and unabashedly spoken out on the topic of the American cut, claiming that the alterations caused the filmmaker a great amount of emotional pain. And with Leone passing due to a massive heart attack several years after the movie’s release, James Woods even asserted that he died of a broken heart. For one of the greatest movies about America ended up being massacred beyond compare and presented to the American people in its lesser, far inferior form. “I’ve always had the sensation that people in America are always avant-garde,” Leone told Marlaine Glicksman in a 1987 interview, “Very attentive to all the new innovations. But it’s very specialized. The American public is a very specialized public. The reason it is taken as a realistic film is because inside the fable, I’ve put that kind of reality in. And it could easily be called, instead of Once Upon a Time in America, Once Upon a Time There Was a Certain Kind of Cinema. Because it was also an homage to cinema. And there’s my pessimism. Because I didn’t know yet that type of film is always going to become more extinct, that there won’t be anymore. Because there will always be more films that win five Oscars like Terms of Endearment.”

Luckily, efforts would later be made to restore the 269-minute version that even European audiences did not get to see. It was announced in 2011 that the director’s original cut was to be re-created in an Italian film lab and that the process would be supervised by Fausto Ancillai, the movie’s original sound editor, and Leone’s children, who had the Italian distribution rights. But due to unexpected legal issues regarding certain deleted scenes, the cut ended up being 251 minutes long. This restored version premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2012 thanks to the efforts of Martin Scorsese, whose Film Foundation assisted with the restoration, which is now available on DVD/Blu-ray. Meaning that the movie can finally be viewed as it was meant to, with the ambiguous ending remaining intact and open to as much interpretation as ever.

Was Max’s implied fate what had really come to pass? James Woods himself cannot be sure, for the director did not tell and even used a stand-in to shoot the scene in question. Or was the entire movie just an opium-induced dream of Noodles’, with the past being something he vividly remembered and the future that which he envisioned, so as to alleviate the guilt he felt for the actions he took? Leone himself did not oppose this theory, but rather confirmed that it just might be the case. Whatever his true intentions were, it is safe to say that the Italian auteur’s swan song will remain one of the most important chapters in the history of American cinema.

Koraljka Suton is a member of the Croatian Society of Film Critics and has a master’s degree in German and English. For her thesis, she did a comparative analysis of Spielberg’s ‘Band of Brothers’ and ‘The Pacific’. Koraljka trained at a Zagreb-based acting studio for six years and fell in love with Michael Chekhov and Lee Strasberg’s acting techniques. She is also a contemporary dancer and a Reiki master who believes in the transformative quality of art. Read more »

A Fable for Adults: Sergio Leone interviewed by Elaine Lomenzo, Film Comment Vol. 20, No. 4, July-August 1984.

It’s a warm, sunny March day at Cinecittà, and the film Sergio Leone has been trying to make for ten years is now in the final days of shooting. Leone hovers over an editing table, absorbed in the action on the screen, with his producer, assistants, and interpreter at his side. The battle with his North American distributor, The Ladd Company, is at this moment not even a cloud on the Rome horizon. For now Leone can toil to make his $45-million dream come true. Once Upon a Time in America is based loosely on a book called The Hoods, written by Harry Goldberg under the pseudonym Harry Grey. In this autobiographical novel Goldberg recalls his experiences in the Prohibition Era, and attempts to explode the romanticized image of Gangsterism given us by Hollywood. After long talks with Goldberg, Leone began to translate into cinematic proportions the ways in which certain myths take precedence over reality. As we enter Leone’s favorite trattoria, you know this man has presence. Four maitre d’s greet us, and walking past the antipasto table, Leone nonchalantly samples each dish with his chubby fingers. On his way out, Federico Fellini, paying tribute to Leone’s reputed appetite, presents a caricature drawn on a linen napkin of Leone with spaghetti spilling out of his mouth. Only now, in this more comfortable environment, does Leone begin to talk about the genesis of Once Upon a Time in America, his preoccupation with American style and myth, and the indefinable dangerousness that instantly characterizes the American actor, setting him apart from all others.

You’ve been shooting this film for six months, and you are now in the early stages of editing. Are you satisfied with your material? Is the “fun” part over or is it just beginning?

The fun part is with the first idea; the “idea” is forming a stage. Editing is the true making of the film. But here is where the doubt surfaces—which kills all the fun.This film is the first you’ve made after ten years. Does this create a pressure on you to continue in a style similar to your famous westerns?

This question of style, it is something indecipherable. Style comes on its own; it’s part of you, part of all your experiences. The minute you try to change “styles” means that you are going to go into mannerisms or something that has nothing to do with your own vision of the world. Style has to do with that particular vision of how things are. Cinematically speaking, style means your own personal way of telling a story. It can be applied in telling a story about a cowboy or gangster or anyone. For example, any good assistant to any good director has to be light years away from his maestro, from his director. If you imitate him 100 percent, you don’t become anything but an imitation of the man you’ve worked with.Sure, but you can recognize a master’s influences and still draw on your own resources.

That’s true, but it comes on its own, afterward. When you’re taken with somebody’s style, you might consciously or unconsciously imitate it. That’s the thing to avoid, because the minute you do that out of an admiration for style you become a bad copy of the original. And so a good first assistant is better off if he works with bad directors, because he somehow maintains himself, learns all the other things, and comes out with his own style. Bad directors amplify your own sense of imagination. Above all, they give you a sense of limitation in that you know what you shouldn’t do. On the other hand, you can have an experience next to a director you love very much but to avoid becoming his bad copy, you have to get away and do your own expression.What is it about the myth of the Epic-West and now the East of Jewish gangsters that fascinates you so? After 20 years of filmmaking, you draw your inspiration from the American fairy tales. Especially since Vietnam and the Nixon years, America seems to be a dirty word in Europe.

I’m fascinated with America—more fascinated with America than American myths or fables. I have a fascination with certain American writers who helped form my youth: Chandler, Dos Passos, Hammett, Hemingway, Fitzgerald. But these writers are only important to me in that they are part of my memory bank and my childhood. When I think of them I see my own childhood. This is also thematic in terms of the film I’m doing right now, in the sense that it is a film based on memory. Inside the film are all the images that I like. There’s an homage to a certain type of filmmaking that I love or cinema that I love. There’s an homage to the script writers who for better or worse helped me to discover the America that I didn’t know, and those who helped me to dream about America.What do you know about the country besides what you’ve gathered from these writers? Have you spent any time in America other than the “casting time” that is behind closed doors?

I can’t see America any other way than with a European’s eyes, obviously; it fascinates me and terrifies me at the same time. The more I love her [America] the more I feel light years away from her. I’m aware of becoming a part of a generation that is now becoming decrepit—Europe is old and decrepit and I feel part of that generation of Europeans more than Americans. I’m fascinated by the youthful aspect of Americans even when it includes contradictions, and naive qualities of being incredulous at certain things. It’s this mixture of all these things—the contradictions, the youth, the growing pains—that makes it fascinating, that makes it unique. America is a dream mixed with reality. The most beautiful thing is that in America, without any notice, suddenly, dream becomes reality, reality becomes dream. That’s the thing that touches me the most. America is like Griffith and Spielberg together. It’s Watergate and Martin Luther King at the same moment. It’s Johnson and Kennedy. All those contrasts: dream and reality always clashing together. Since we don’t know each other, I want to give you a complete picture of myself, why I’m interested in America, why I’m always occupying myself with America: because in America, there’s the whole world. In Italy there’s Italy and in France there’s France. The problems of America are the problems of the whole world: the contradictions, the fantasies, the poetry. The minute you touch down on America, you touch on universal themes. For better or worse, that’s the way it is.But America is constantly being accused of cultural imperialism by Europe?

I don’t agree with that. I don’t think it’s right to accuse her of that, because America being a giant nation occupies herself first with trying to content her own country. And this is a big problem for America, trying to make Americans content. It’s a giant problem because the country is nude up of many, many countries put together. To arrive at satisfying all the varied tastes of Americans means to get to a point of satisfying all the tastes worldwide: worldwide needs, tastes, fantasies. That’s why Americans have no problems in terms of film or TV. The images go out into the world and meet the same needs of other peoples, because of that universal collective consciousness.There are certain themes that run through your new film: solidarity with the outcasts of society, choices dictated by despair, closeness of male friendships, betrayal, violence and corruption, which also ran through your earlier films. Do you see these themes as “American”?

I’m trying to do a film that can’t easily be categorized. It’s not a realistic film, not historical. It’s fantastic, it’s a fable. I force myself to make fables for adults.But you do deal with those questions?

There are themes that are inside of me. Friendship, for example, is a theme I feel very much, maybe because I was an only child. Obviously all these themes come up because they play a major part in my own psyche. And I’m essentially a Roman, which doesn’t necessarily mean being essentially Italian. It means something else because Romans are a separate race. Romans always have a paradoxical sense about things; they have an unfettered sense of irony and self-criticism. The irony is almost always placed against themselves or made in terms of themselves. All of this put together means that I put into my films certain of my own phantoms or ghosts. Sometimes if I choose settings for my films that are underdeveloped or slightly criminal, it’s also to make the point that sometimes the good guy, if you scrape a little of the varnish off, is a little less good, and the bad guy, with a little less of the “bad guy” varnish, is a little less bad. There’s a small Roman story: A cardinal dies who did good and bad. The bad he did very well and the good he did very badly.Let’s talk a little about the talent you came across in America. Was it difficult casting this film? Is there a perceptible difference between the talent in America and the talent in Europe? If so, what in your opinion accounts for this?

The talent in America is based first of all on the number of people, and then this blind love they all have on arriving or becoming—whether it’s an actor, director, or whatever else. It takes them up to some extreme type of sacrifice. I’ve never seen stars work as waiters in any other part of the world; in America, they do, they start off that way. This means they choose a very humble work in order to be exclusively at the service of their art. They are taken in and totally absorbed by their ambition, their dedication to the arts. There’s a common factor involved in all of this. They always say that Neapolitans are naturally born actors. I would say that they are natural comics, and that Americans are natural actors. They are helped enormously by the extreme richness of language.Could it also be something to do with the freedom that Americans have, politically, socially, culturally? As children it’s part of our cultural experience to have choice: to wear what we want, to say what we want, to eat what we want, to live where we want, to move away from the family, and so forth.

Yes, total liberty from infancy on. Children are exposed to everything. People talk in front of them and together with them. A 50-year-old can be friends with someone who’s ten. All those things are a result of that liberty, and they provide an enormous sense of spontaneity, an enormous amount of security and a great availability to acting and to delivery. Thus, whoever really loves this work then chooses to study it, very well and precisely, whether it’s with Actors Studio or wherever—ten or twenty-methods of approach to this kind of work, mixed with an intense process of study. Consummate actors are the product. We don’t have that here. Our resources are almost always more geared to immediate spontaneity and immediate contact with people more than the form of expression used. A spontaneous actor in Italy, if he’s young and spontaneous, can only be broken down by an acting school in Italy, not encouraged or taken to a point of higher expression. He will be restrained. That’s why neo-realism was born in Italy. Because in that moment it was impossible to use professional actors to report the times they were living in at that point. It became false and studied and manneristic.How do you manage to communicate with your cast when you don’t speak English? I have this picture of you “conducting” them, rather than “directing” them.

I use an extrasensory imagination, where I use no language. This relationship is particular, certain nuances have to be created. The use of words eliminates these nuances or “sits on them.” In this process of directing there becomes an extrasensory demonstration between the actor and myself. A “felt” relationship between actors and myself specifically, because there is no verbal dialogue.On this film Robert De Niro collaborated with you on the casting. Is this a practice that you’d repeat?

I’d repeat it immediately with him. He was much faster than I could be at understanding whether a New York accent would lie right on an actor or not. He always left the total responsibility on me to decide on the actor’s quality in terms of his delivery or acting, and the same for physical characteristics. That choice was left to me. He was a great collaborator.I’d like you to talk about your long relationship with composer Ennio Morricone. At what point do you discuss the music for your films? Before, during, or after the shooting? Do you almost hear the music while you’re shooting or is the music a direct result of the action?

I talk about the music of the film long before the filming begins. I have the music programmed before I begin shooting, so I can use it while I’m shooting. For me, the music is part of the dialogue, and many times much more important than the dialogue. It becomes an expression in itself.So the music is number one in part of this process, and you direct to the sound and beat of the music?

When we’re not using direct sound for dialogue it’s much easier. When we’re using direct sound, obviously we can’t use music as the background, because it would ruin the sound. But I do play my music on the set whenever I can for the actors.But the music plays in your head constantly?

The work is done originally for me. I discuss it with Morricone months ahead of time, and the music guides me through the film in terms of certain sentiments or emotions. I have him create ten or fifteen or twenty themes before choosing one. Because the one I choose is the one that gives me the most primary sensation about what the intensity of that particular moment or pan of the film is. The first musical test. I make on myself.Now that you’ve finished filming, are you developing any other projects that you would like to discuss?

No, because at this moment or phase in production, I’m still taken with idiosyncrasies that occur during the making of the film. I’m also taken with a love for the project that I have—the amount of love needed to take the film to the end and finish it. I have another sentiment, too: I always think this is the last film I will make.You have said throughout that you draw a lot on the past. But what about your life now? What influences affect your art now? Are they perceptible, or is this a moot question?

By indicating the past we can discover the future.Where does that leave the present?

The present is transitory. It’s only right that the present should become the past or immediately the future. The present today is what counted yesterday or tomorrow. For tomorrow to become better you should take a look again at yesterday.

“I’M A HUNTER BY NATURE, NOT A PREY”

An interview with Sergio Leone from the pages of the June 1984 issue of American Film written by Pete Hamill. Throughout the candid interview, it’s clear filmmaking is a sacred belief to Leone who hails from a family steeped in the tradition of filmmaking. Often attributed with perfecting the spaghetti western genre with A Fistful of Dollars (1964), The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) and Once Upon a Time in the West (1968), Leone developed an artistic voice with a precise knack for uncovering the raw realities of the often cartoonish and glamorized American Wild West conceived by Hollywood during the 1950s. Leone confides to Hamill about the arduous and lonely process of filmmaking throughout the 10-year process on what would be his last and arguably greatest film. Here he speaks to the sacraments of technical filmmaking and his devoted belief in the idealized American dream with the sentiment, “America is the determined negation of the Old World, the Adult World.”

During the filming of Once Upon a Time in America, Sergio Leone was generally unavailable for interviews. However, earlier this spring, he found time to talk about his approach to filmmaking. The interview took place in Rome and was translated by Michel De Matteis.

When you were a boy, was there an America in your head?

Yes, certainly, as a child, America existed in my imagination. I think America existed in the imaginations of all children who bought comic books, read James Fenimore Cooper and Louisa May Alcott, and watched movies. America is the determined negation of the Old World, the adult world. I lived in Rome, where I was born in 1929, when it was the capital of the imperial Mussolini melodrama—full of lying newspapers, cultural ties with Tokyo and Berlin, and one military parade after another. But I lived in an anti-Fascist family, which was also devoted to the cinema, so I didn’t have to suffer any ignorance. I saw many films. Anyway, it was mainly after the war that I became decisively enchanted by the things in Hollywood. The Yankee army didn’t only bring us cigarettes, chocolate bars. Am-lire army-issue money, and that peach jam celebrated by Vittorio De Sica in Shoeshine—together with all this, they brought a million films to Italy, which had never been dubbed into Italian. I must have seen three hundred films a month for two or three years straight. Westerns, comedies, gangster films, war stories—everything there was. Publishing houses came out with translations of Hemingway, Faulkner, Hammett, and James Cain. It was a wonderful cultural slap in the face. And it made me understand that America is really the property of the world, and not only of the Americans, who, among other things, have the habit of diluting the wine of their mythical ideas with the water of the American Way of Life. America was something dreamed by philosophers, vagabonds, and the wretched of the earth way before it was discovered by Spanish ships and populated by colonics from all over the world. The Americans have only rented it temporarily. If they don’t behave well, if the mythical level is lowered, if their movies don’t work any more and history takes on an ordinary, day-to-day quality, then we can always evict them. Or discover another America. The contract can always be withheld.Your father, Vincenzo Leone, was a film director. How did that affect your first impression of films?

As a child, I was convinced that my father had invented the cinema himself. I knew that my father was Santa Claus and that, on the other side of the cinematic field, beyond the geometric lines of the screen, great masses of technicians, makeup artists, scene shifters, and hairdressers crowded in. I knew all about electric cables, cameras, microphones, reflectors. It’s probably also because of this that the technical side of my moviemaking is so important. I go to the dubbing room as if I’m going to Mass, and mixage, for me, is the most sacred rite. I think filming itself is fun, especially in Death Valley and under the Brooklyn Bridge, where coyotes cry and ships toot their horns. But the Moviola is the altar of a voodoo rite. One sits down in front of the console and plays his hand with the heights of the heavens. I always knew that films were made by men and structured like prayers.Could you describe the arduous process of coming up with a screenplay for Once Upon a Time in America?

It was after I made The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly that the subject of Once Upon a Time in America began to buzz in my ears. I found this book, The Hoods, by Harry Gray, in a Rome bookshop. More than anything else, it was a perfect and loving hymn to the cinema. The story of these Jewish gangsters—unlucky three times over and determined five times over to challenge the gods—attached itself to me like the malediction of the Mummy in the old movie with Boris Karloff. I wanted to make that film and no other. We began to procure rights to the cinematographic adaptation, which, however, was already in the hands of other film-world hombres. It wasn’t very easy, but we finally managed, with cleverness and many dollars, to rip off the rights from the legitimate holders. That was already the first sign of where things were heading. Then the infernal screenplay-writing season began. Norman Mailer was among the first to work on it. He barricaded himself in a Rome hotel room with a box of cigars, his typewriter, and a bottle of whiskey. But, I’m sorry to say, he only gave birth to a Mickey Mouse version. Mailer, at least to my eyes, the eyes of an old fan, is not a writer for movies. Mysterious arguments within the production cropped up—material problems and supernatural problems, metaphysical mess-ups of every type—and each successive screenplay came out inferior to the concept. And then, a long time after I had willingly gone over to the enemy—that is, to the production side—there was this meeting with Arnon Milchan, who, before dedicating himself to cinematographic production, must have been employed as an exorcist at some Gothic cathedral. The fact is that everything, from one moment to the next, began to take form. Leo Benvenuti and Stuart Kaminsky, the detective writer and the film devotee, miraculously concluded the screenplay, the sun shone again in the sky and away we all went to the great adventure. We worked solidly for two years straight and we finally reached port, it seems to me, with banners waving in the wind and the crew intact.You seem to be fascinated with American myths, first the myth of the West, now that of the gangster. Why is this?

I am not fascinated, as you say, by the myth of the West, or by the myth of the gangster. I am not hypnotized, like everyone east of New York and west of Los Angeles, by the mythical notions of America. I’m talking about the individual, and the endless horizon—El Dorado. I believe that cinema, except in some very rare and outstanding cases, has never done much to incorporate these ideas. And if you think about it, America itself has never made much of an effort in that direction either. But there is no doubt that cinema, unlike political democracy, has done what it can. Just consider Easy Rider, Taxi Driver, Scarface, or Rio Bravo. I love the vast spaces of John Ford and the metropolitan claustrophobia of Martin Scorsese, the alternating petals of the American daisy. America speaks like fairies in a fairy tale: “You desire the unconditional, then your wishes are granted. But in a form you will never recognize.” My moviemaking plays games with these parables. I appreciate sociology all right, but I am still enchanted by fables, especially by their dark side. I think, in any case, that my next film won’t be another American fable. But I say that here and I deny it here, too.Why does the Western seem to be dead as a movie genre? Has the gangster film taken its place?

The Western isn’t dead, either yesterday or now. It’s really the cinema—alas!—that’s dying. Maybe the gangster movie, in contrast to the Western, enjoys the precarious privilege of not having been consumed to the bones by the professors of sociological truth, by the schoolteachers of demystification ad nauseam. To make good movies, you need a lot of time, a lot of money, and a lot of goodwill. And you need twice as much of it today as you needed yesterday. And the old golden vein, in California’s movieland, where these riches once glistened so close to the surface, unfortunately seems almost completely dried up now. A few courageous miners insist on digging still, whimpering and cursing television, fate, and the era of the spectaculars which impoverished the world’s studios. But they are dinosaurs, delivered to extinction.What was it that you saw in Clint Eastwood that no one in America had seen at that time?

The story is told that when Michelangelo was asked what he had seen in the one particular block of marble, which he chose among hundreds of others, he replied that he saw Moses. I would offer the same answer to your question—only backwards. When they ask me what I ever saw in Clint Eastwood, who was playing I don’t know what kind of second-rate role in a Western TV series in 1964, I reply that what I saw, simply, was a block of marble.How would you compare an actor like Eastwood to someone like Robert De Niro?

It’s difficult to compare Eastwood and De Niro. The first is a mask of wax. In reality, if you think about it, they don’t even belong to the same profession. Robert De Niro throws himself into this or that role, putting on a personality the way someone else might put on his coat, naturally and with elegance, while Clint Eastwood throws himself into a suit of armor and lowers the visor with a rusty clang. It’s exactly that lowered visor which composes his character. And that creaky clang it makes as it snaps down, dry as a martini in Harry’s Bar in Venice, is also his character. Look at him carefully. Eastwood moves like a sleepwalker between explosions and hails of bullets, and he is always the same—a block of marble. Bobby, first of all, is an actor. Clint, first of all, is a star. Bobby suffers, Clint yawns.Does it surprise you that an actor could become president of the United States? Should it have been a director?

I’ll tell you, very frankly, that nothing surprises me any more. It wouldn’t even surprise me to read in the newspapers that a president of the United States, for a change, had become an actor. I wouldn’t be able to hide my surprise if all he did was take on worse films than those done by certain actors who became presidents of the United States. Anyway, I don’t know many presidents, but I do know too many actors. So I know with certainty that actors are like children— trusting, narcissistic, capricious. Therefore, for the sake of symmetry, I imagine presidents, too, are like children. Only a child who became an actor and then a president, for example, could seriously believe that The Day After concealed who knows what new yellow peril. A director, if possible, would be the least adapted of any to be president. I can picture him more as the head of the Secret Service. He would move the pawns and they would dance, accordingly, to the end, to produce, if nothing else, a good show. If the scene works, great. Otherwise, you redo it. Old Yuri Andropov, if he had been a director instead of a cop, would have enjoyed greater professional satisfaction and—who knows?—he might have lived longer.Most of your films are very masculine. Do you have anything against women?

I have nothing against women, and, as a matter of fact, my best friends are women. What could you be thinking? I tolerate minorities. I respect and kiss the hand of the majorities, so you can just about imagine then how I genuflect three or four times before the image of the other half of the heavens. I even, imagine this, married a woman, and, besides having a wretch of a son, I also have two women as daughters. So if women have been neglected in my films, at least up until now, it’s not because I’m misogynist, or chauvinist. That’s not it. The fact is, I’ve always made epic films and the epic, by definition, is a masculine universe. The character played by Claudia Cardinale in Once Upon a Time in the West seems a decent female character to me. If I can say so, she was a fairly unusual and violent character. At any rate, for a couple of years now. I’ve been harboring the notion of a movie about a woman. Every evening, before going to sleep. I rummage over in my mind a couple of not bad story ideas for it. But either out of prudence or superstition—as is only human, and even too human, I prefer not to talk about it now. I remember that once in 1966 or ’67, I spoke with Warren Beatty about my project for a film on American gangsters and, a few weeks later, he announced that he would produce and star in Bonnie and Clyde. All these coincidences and visions disturb me.How do you think you fit among the Italian and other European directors? Which directors do you admire? Which are overrated?

Yes. without a doubt, I, too, occupy a place in cinema history. I come right after the letter L in the director’s repertory, in fact a few entries before my friend Mario Monicelli and right after Alexander Korda, Stanley Kubrick, and Akira Kurosawa, who signed his name to the superb Yojimbo, inspired by an American detective novel, while I was inspired by his film in the making of A Fistful of Dollars. My producer [on that film] wasn’t all that bright. He forgot to pay Kurosawa for the rights, and Kurosawa would certainly have been satisfied with very little and so, afterwards, my producer had to make him rich, paying him millions in penalties. But that’s how the world goes. At any rate, that is my place in cinema history. Down there, between the K’s and the M’s generally to be found somewhere between pages 250 and 320 of any good filmmakers directory. If I’d been named Antelope instead of Leone, I would have been number one. But I prefer Leone; I’m a hunter by nature, not a prey. To get to the second part of the question, I have a great love for the young American and British directors. I like Fellini and Truffaut. However, I’m not an expert on overrating. You should ask a critic—the only recognized experts on over-, under-, or tepid ratings. The critic is a public servant, and he doesn’t know who he’s working for.Which comes first: the writer or director?

The director comes first. Writers should have no illusions about that. But the writer comes second. Directors, too, should have no illusions about that.What advice would you have for young people who want to be directors?

I would say, read a lot of comic books, watch TV often, and, above all, make up your minds that cinema is not just something for snobs, other moviemakers, and the mothers of petulant critics. A successful movie communicates with the lowbrow and the highbrow public alike. Otherwise, it’s like a hole without the doughnut around it.F. Scott Fitzgerald once said, “Action is character.” Do you agree?

The truth is that I am not a director of action, as, in my view, neither was John Ford. I’m more a director of gestures and silences. And an orator of images. However, if you really want it. I’ll declare that I agree with old F. Scott Fitzgerald. I often say myself that action is character. But it’s true that, to be more precise, I say, “Ciack! Action and character, please.” Certainly we must mean the same thing. At other times—for example when I’m at the dinner table—I sometimes say, “Ciack! Let’s eat. Pass the salt.”When you’re not making movies, what do you do?

I will confess that since I was a child, when no one dreamed of asking me these questions, I always imagined I would respond with a preemptory and dry “Stop right there! Nothing doing. I won’t even hear of it. My privacy is sacred and I have no intention of putting it on display in the piazza just for the amusement of nosy journalists like you.” I try, every time, but then they shame me like a dog and I end up admitting all the horrible truth. That is, the following: that I sunbathe, go to the movies and to the stadium, think about my next films, read books and screenplays, meet friends, go on vacation sometimes, play chess and hang around the house irritating my family with, what’s worse, superfluous observations. I’m very fond of my family, as all Italians are, including Lucky Luciano and Don Vito Corleone, but I wouldn’t know how to talk to them. They say they put up with me, but the truth is that I put up with them.Now that you’ve finished Once Upon a Time in America, are you able to step back and assess the film?

Once Upon a Time in America is my best film, bar none—I swear—and I knew that it would be from the moment I got Harry Gray’s book in my hand. I’m glad I made it, even though during the filming I was as tense as Dick Tracy’s jaw. It always goes like that. Shooting a film is awful, but to have made a movie is delicious.

When Sergio Leone made ‘Once upon a Time in America,’ it was an event. Here was the man who had invented the spaghetti Western, coming to New York to make a Jewish gangster epic. Everybody, including my friends Bob De Niro and Joe Pesci, was in it; everybody in New York was working on it. We all knew it would be unlike anything we’d ever seen. The version released in the summer of 1984 pleased no one, Leone least of all. The much longer cut that came out later that year restored his extraordinary Proustian structure, but it was missing 40 minutes that Leone felt to be crucial to his grand, 20th-century canvas. Recently, with the help of the Leone family, 25 minutes of material was found, including an extended excerpt from Antony and Cleopatra, featuring Elizabeth McGovern, and a long-rumored exchange between De Niro and Louise Fletcher. These scenes and others have now been re-inserted into the picture, and the restoration—a collaboration involving the Cineteca di Bologna, L’Immagine Ritrovata, and the Film Foundation—is nearly complete. A great film just became that much greater. —Martin Scorsese

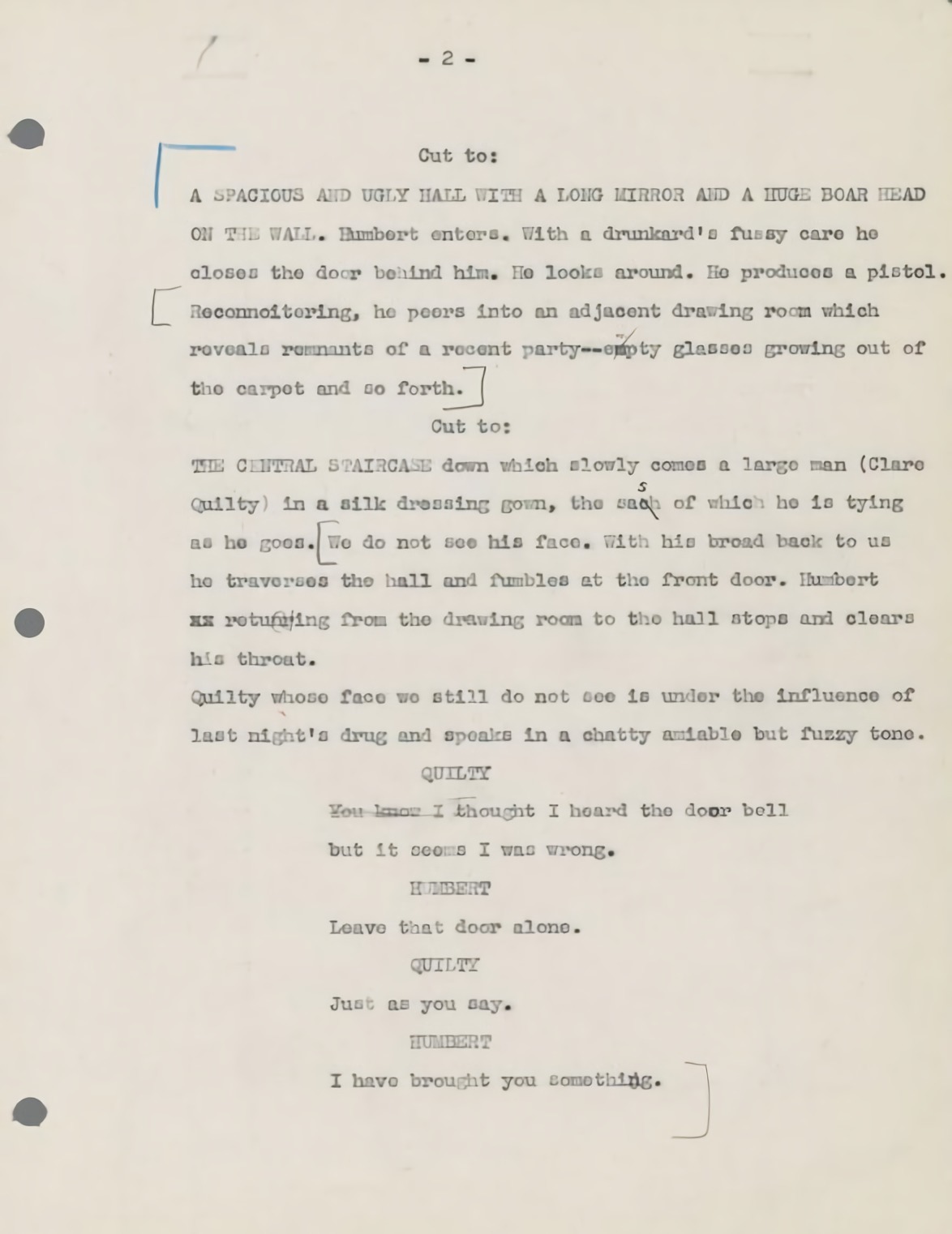

Screenwriter must-read: Leonardo Benvenuti, Piero De Bernardi, Enrico Medioli, Franco Arcalli, Franco Ferrini & Sergio Leone’s screenplay for Once Upon a Time in America [PDF]. (NOTE: an early script by David Mills which differs from the finished film; for educational and research purposes only). The DVD/Blu-ray of the film is available at Amazon and other online retailers. Absolutely our highest recommendation.

Loading...

Loading...

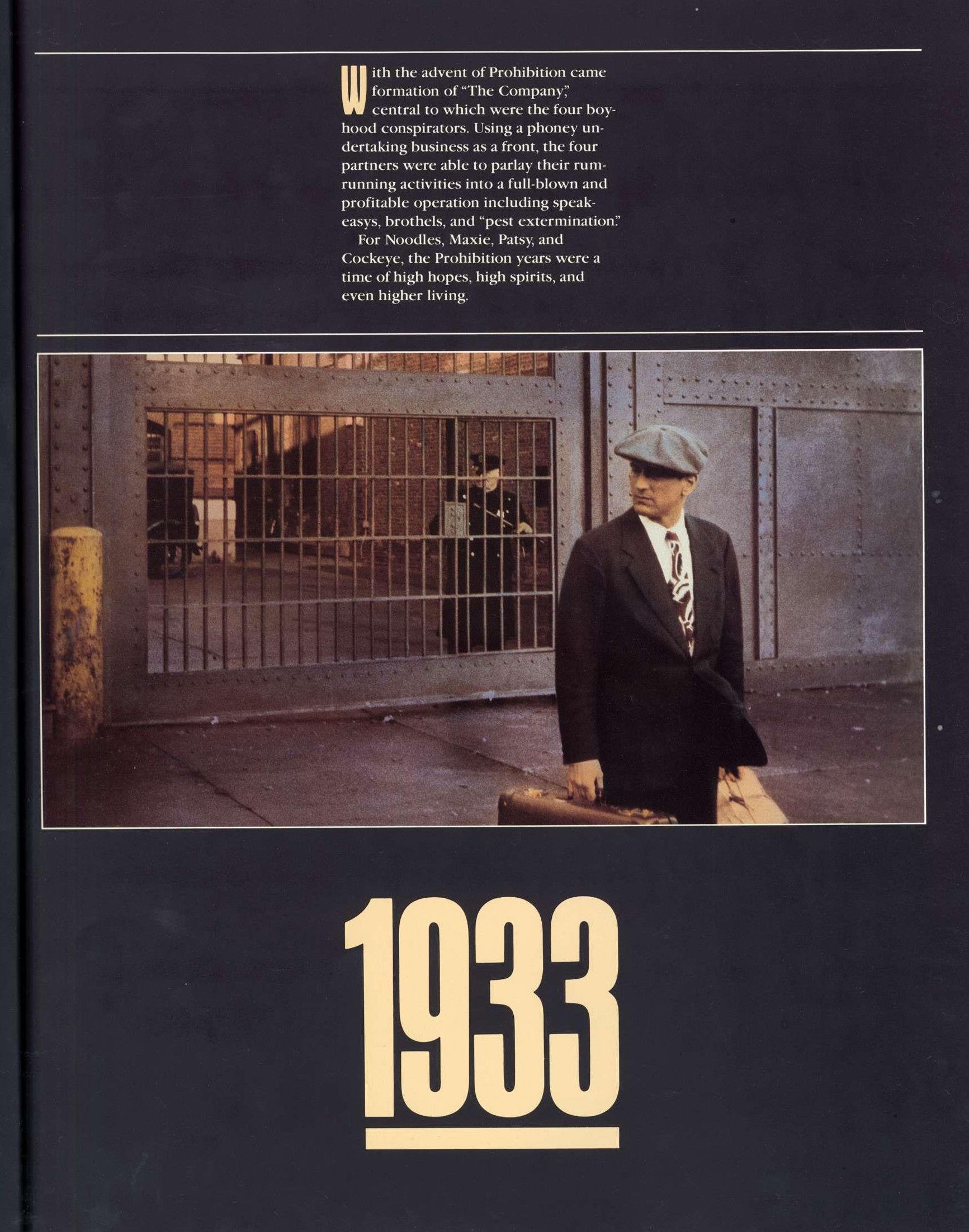

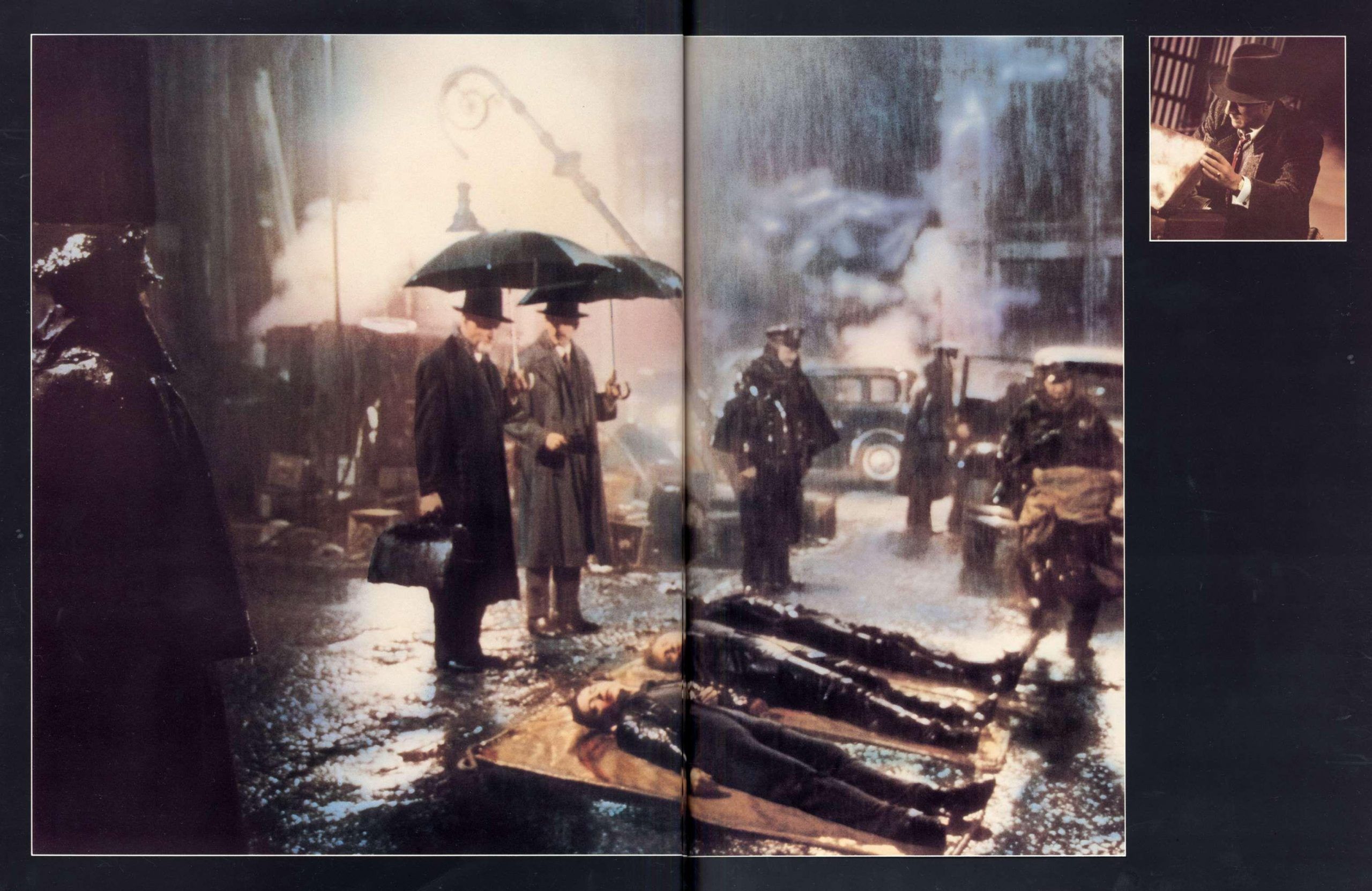

Here is a great booklet and press kit from the 1984 Sergio Leone’s epic masterpiece, courtesy of CineFiles.

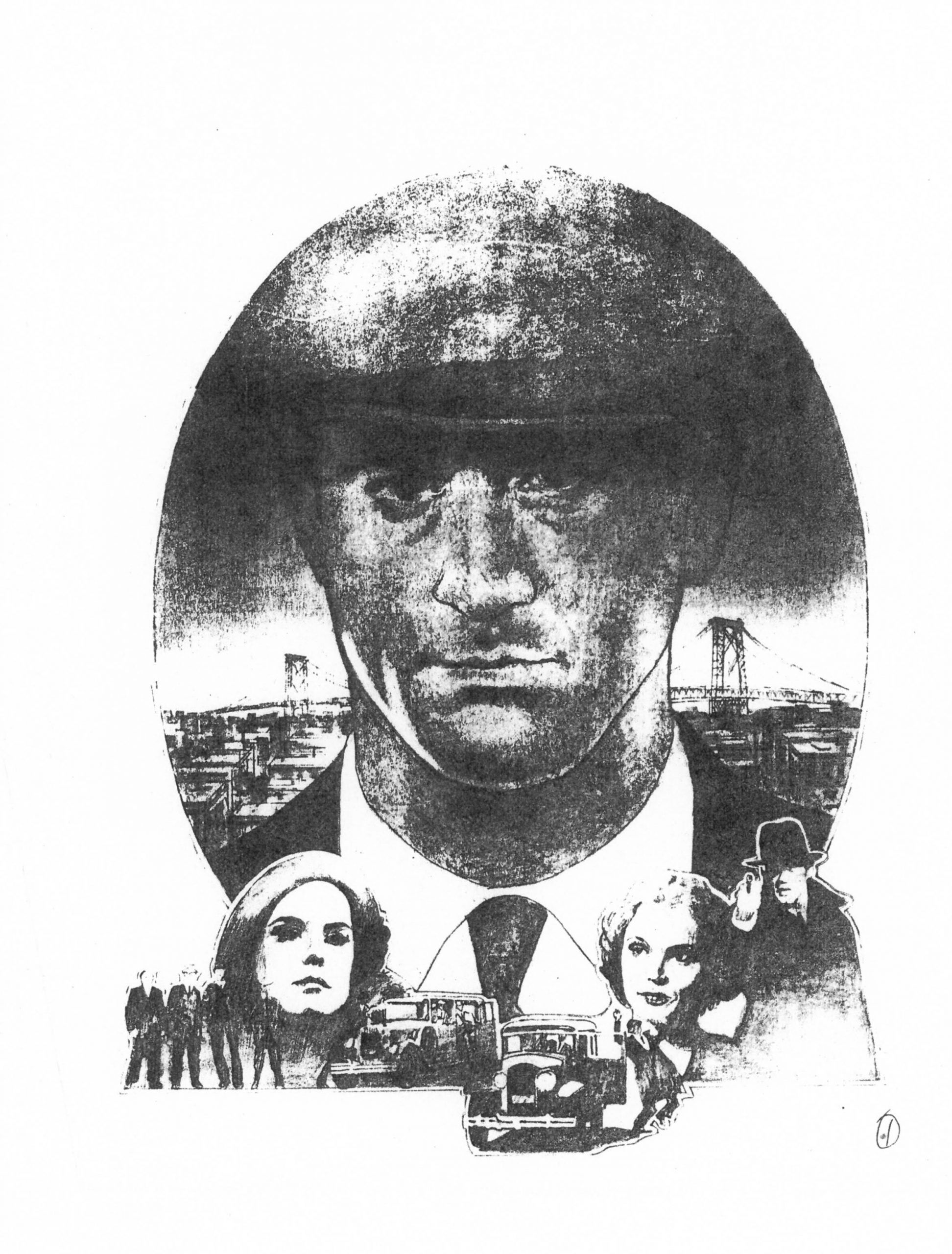

From the Tom Jung papers, this sketch is one of several conceptual designs pitched for the film’s poster art.

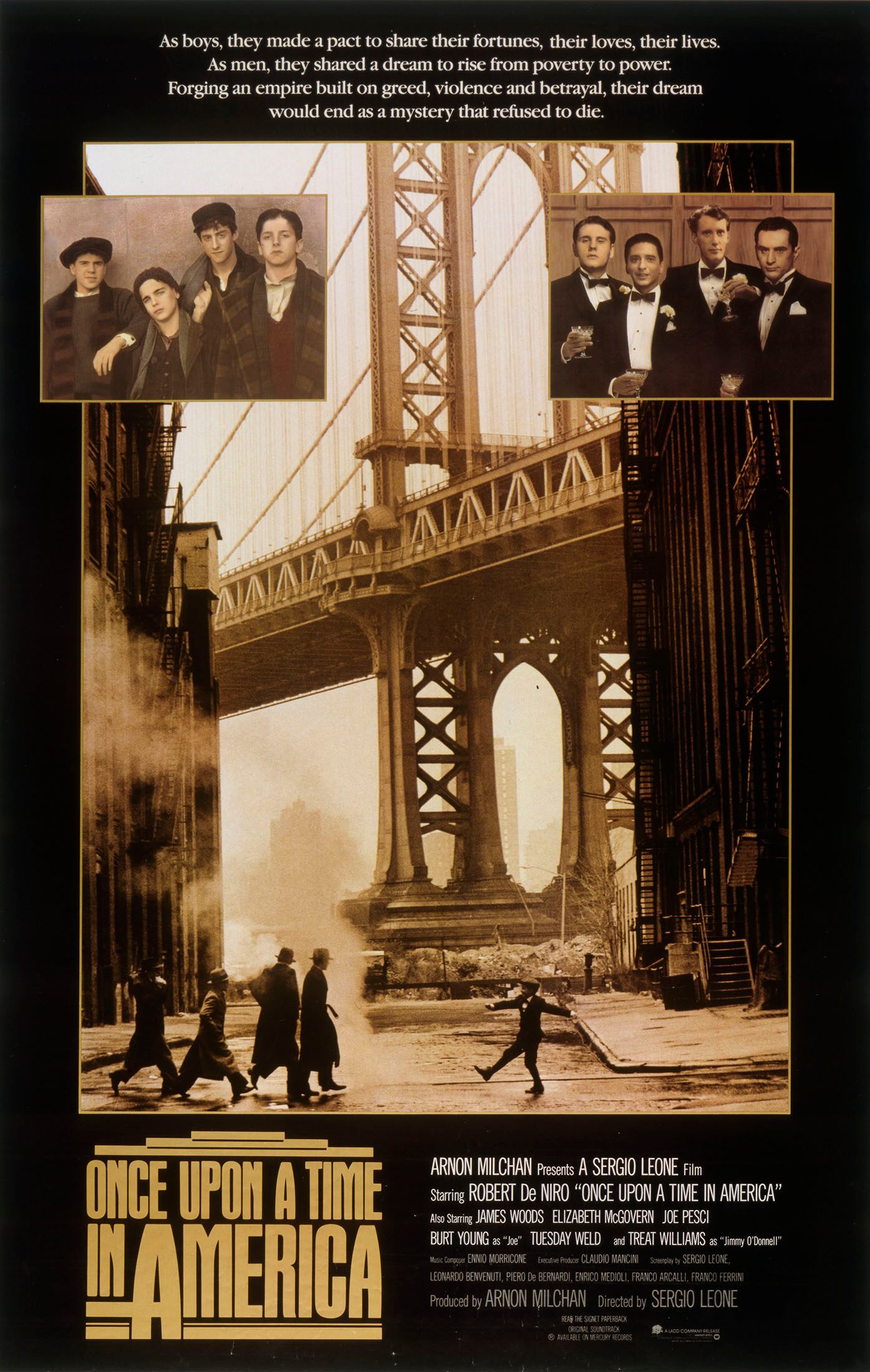

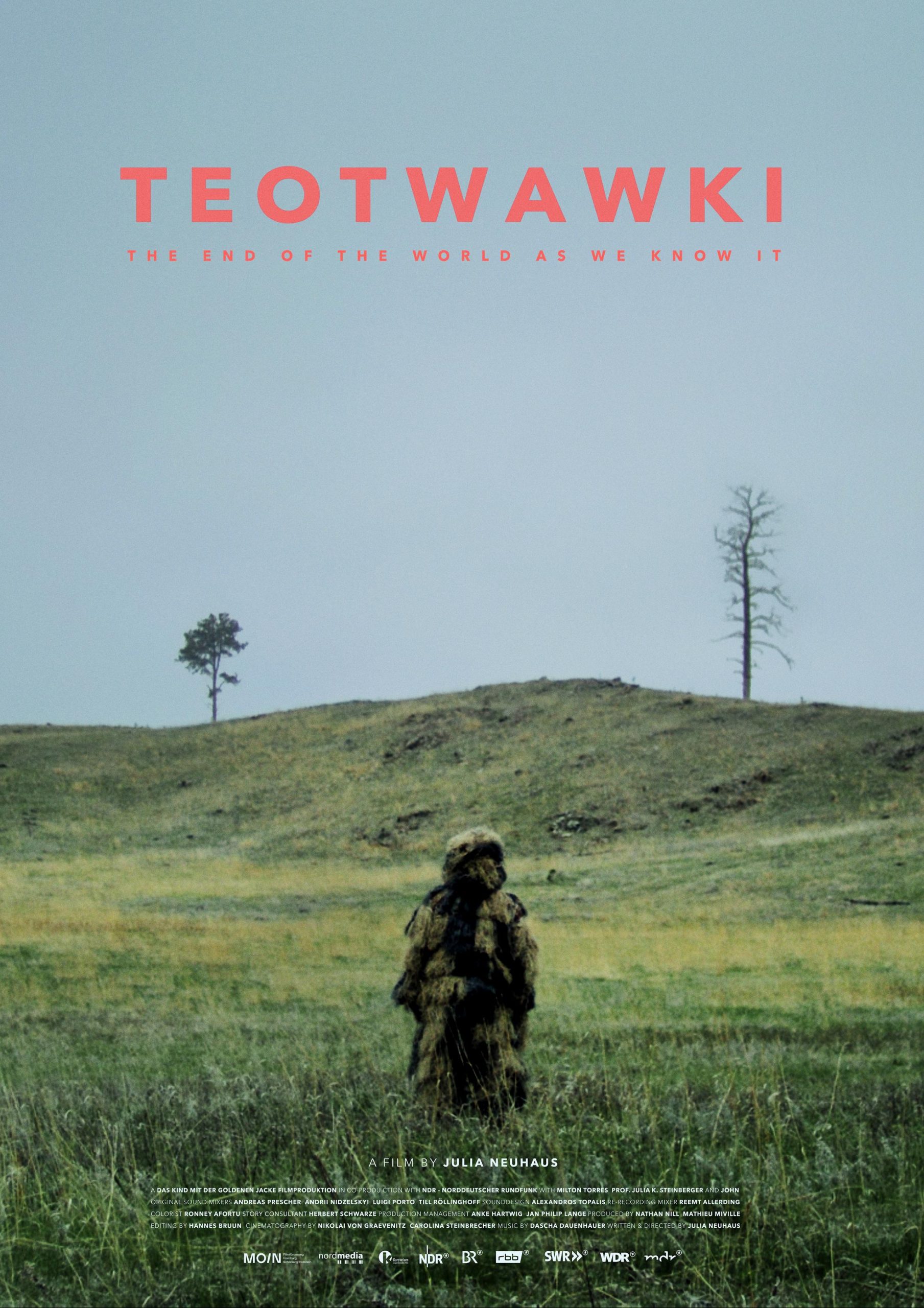

U.S. theatrical poster art.

Short documentary Once Upon a Time: Sergio Leone profiling the making of the film.

A documentary commission by Film4 that was first broadcast in 2000.

Robert De Niro talks about Sergio Leone, Once Upon a Time in America and Harry Grey’s book The Hoods.

ENNIO MORRICONE

There is a lot of talking, of listening to things. Quite frequently, everything is scrapped and we start again from scratch. Often when everything has been accepted Sergio starts to doubt the decision and then more doubts come. It becomes a very complicated process that has to be endured. But it is quite normal that it should be like this; it doesn’t upset me, or even bother me, because it means that when a decision is finally made it is the right one. —Ennio Morricone

From Christopher Frayling’s book, Sergio Leone: Something to Do with Death.

The music in Once Upon a Time in America plays a important role in keeping with the general atmosphere of melancholy.

The shooting script was full of explicit references to musical themes. But Sergio Leone had strong views about the particular melodies he wanted, which owed nothing to Harry Grey and a great deal to his own biography: ‘I asked for a different kind of score from Ennio Morricone this time. We began with a song of the period—“Amapola”. And I wanted to add to this some very precise musical themes: “God Bless America” by Irving Berlin, “Night and Day” by Cole Porter, “Summertime” by Gershwin. In addition to the original score by Morricone, and these “mythic” melodies to conjure up an epoch, I added something from today: “Yesterday” by John Lennon and Paul McCartney. I chose these… because they were such a lucid form of nostalgia in my head and maybe in reality, because for me they were touching base.’

Irving Berlin’s ‘God Bless America’ had been written in 1918 to celebrate the end of the First World War, but it did not become a public anthem until Armistice Day in 1938, when Kate Smith’s live version was recorded. Thus, strictly speaking, associating it with celebrations at the end of Prohibition in December 1933 was a slight anachronism. But the song was another immigrant’s fairy-tale, and Leone wanted the irony of its use in this context. ‘Yesterday’, recorded by the Beatles in 1965, subsequently the most ‘covered’ song in history, was called upon to provide a bridge to the first 1968 sequence, albeit rearranged as muzak. It was to be reprised as if played at the Long Island party, during Noodles’ climactic discussion with Senator Bailey.

Leone had started discussing the music for Once Upon a Time in America immediately after completing Giù la testa, and the score was more or less complete by 1975-6, seven years before a foot of film was shot, which must be a record. Ever since Leone came to Morricone with the ready-made deguello theme for Fistful of Dollars, the composer had been very sensitive about starting with a piece of music found by someone else. On this occasion, though, Carla Leone confirms that ‘“Amapola” was chosen by Sergio’. Originally a Spanish tune by Joseph M. La Calle, it had been given English lyrics by Albert Gamse and become one of the greatest hits of 1924. A 1930s recorded version had been arranged by Jimmy Dorsey. Leone may have been reminded of it in 1971 when he heard the soundtrack of Carnal Knowledge, where Jules Feiffer’s script called for ‘dance music of the forties’ in the opening sequences, and director Mike Nichols selected a version of ‘Amapola’ rearranged by Al Dubin and Harry Warren. In 1989, Morricone reflected, ‘I think Leone’s choice was on this occasion justified. The film needed historical reference-points, whether this one or other well-known pieces, all corresponding to precise dates or events.’66 (After the film was released, ‘Amapola’ re-entered the pop operatic repertory; it reached a sort of apotheosis in the final medley sung by the ‘Three Tenors’ at the Baths of Caracalla in July 1990.)

‘Amapola’ was to be heard first, in a 1924-style arrangement, on Deborah’s wind-up gramophone; later, in an over-lush string arrangement, played by the seaside restaurant orchestra during Noodles’ big night out. The tune was also to be woven into Morricone’s ‘Deborah’s Theme’—transposed from A to E major—as if the two had blended in Noodles’ memory. The ‘found music’ tended to correspond to real moments in the narrative, with its source shown on screen. As did ‘Cockeye’s Song’, played on the pipes of Pan as the children strut their stuff around Delancey Street, and superimposed by Morricone on Hebraic themes to evoke the ethnic community in which they grew up. This was a development of the ‘cross-referencing’ of Leone’s earlier films. As Morricone recalls: ‘The musical construction arose from our conscious mixture of two musics—some from the musical reality of a given epoch, some specially composed. To illustrate the 1920s and 1930s, for example, I carefully kept the orchestration of the period, so that the audience could immediately identify the historical time when the action takes place. Where the original themes were concerned, they had to evoke less palpable things—such as the passage of time, or particular emotions such as nostalgia, love or joy.’

Instead of using the score to beef up big action sequences, or to provide ironic punctuation to the image, for Once Upon a Time in America it would have a quasi-religious feel to it—as if calling Noodles back to his distant past. It had a traditionally melodic feel, in more mainstream arrangements usually in the key of E. As Leone was to put it, ‘This time the emotions were so sharply defined, so strong and so romantic, that we agreed the music ought to be less emphatic than usual… it ought to come from a long way away.’ He opted for the pipes of Pan ‘because Gheorghe Zamfir, the great Romanian concert performer, had enchanted me, and because the pipes are the most haunting of instruments—like a human voice and like a whistle.’ A piece which Leone almost turned down in its early stages, fearing a resemblance to the Once Upon a Time in the West theme, became ‘Deborah’s Theme’. Leone was to remember that ‘this love theme was, I think, originally composed for a Zeffirelli film but was never used’, and its selection continued his time-honoured tradition (going back to Fistful days) of re-evaluating Morricone music that other directors had earlier rejected—and then, when the theme proved to be a success, telling all and sundry how clever he had been to spot its potential.

The theme consists of a series of short, hesitant musical phrases, with a few beats of silence between them: each time they return, the phrases arc enriched with new embellishments, until the climax when the soprano voice of Edda Dell’Orso is introduced. It is a direct musical expression of Noodles’ frustrated desire, compounded by moments from ‘Amapola’. But the human voice, scored as another musical instrument, was much less in evidence in Once Upon a Time in America than in the previous two Leone films. Morricone explains: ‘There is a reason why I used less of Edda dell’Orso’s voice in this particular score… and it was right not to use it in the childhood scenes. The voice seemed perfect for moments which lament the passing of childhood, to lead the audience to think about times past—the thirty lost years of Noodles.’ One such moment was the very last image of the film, when the main title theme was repeated, with soprano harmony, as Noodles inhales the smoke of an opium pipe, lies on his back and, finally, smiles. Such music, said Morricone, ‘comes into the film when the camera looks into the eyes of the character. The theme then singles out what he is thinking at that moment, what is going on inside.’The overture to Rossini’s Thieving Magpie, another piece of ‘found’ music, which accompanies the baby-switching sequence, was selected by Carla Leone, as were some of the jazz inserts played in Fat Moe’s speakeasy. For the ‘Prohibition Dirge’, a stately New Orleans funeral march which turns into hot jazz as the party gets into full swing, Morricone followed the script by providing an arrangement in the mid-1930s style of Louis Armstrong.

The main themes were all composed by 1976, ready for refining and recording when at last the schedule was finalized: Leone intended to play the music on the set ‘with a few instruments, not necessarily the full orchestra’—to create the right atmosphere, focus concentration and ‘to help the chief camera operator find the softness necessary to make tracking shots, as if he was playing a violin’. That was the plan, anyway. Final revisions would take just one month, and recording another. But, as Morricone emphasizes, ‘Sergio and I always think through our work to the very end, without ever declaring ourselves satisfied’. And Leone would keep having second thoughts: ‘Every so often, Sergio, when the music was already written, would phone me and say, “Listen, let’s have a quick meeting—because I’m beginning to have doubts about that theme for Deborah.” Then he would listen to it, and calm down again. Because he still liked it, after all. This went on about every three months… And for the scriptwriters it seemed sometimes as if everything would become a crisis, and they would have to start doing everything all over again. With me, however, he just seemed to want his judgement confirmed every now and again.’

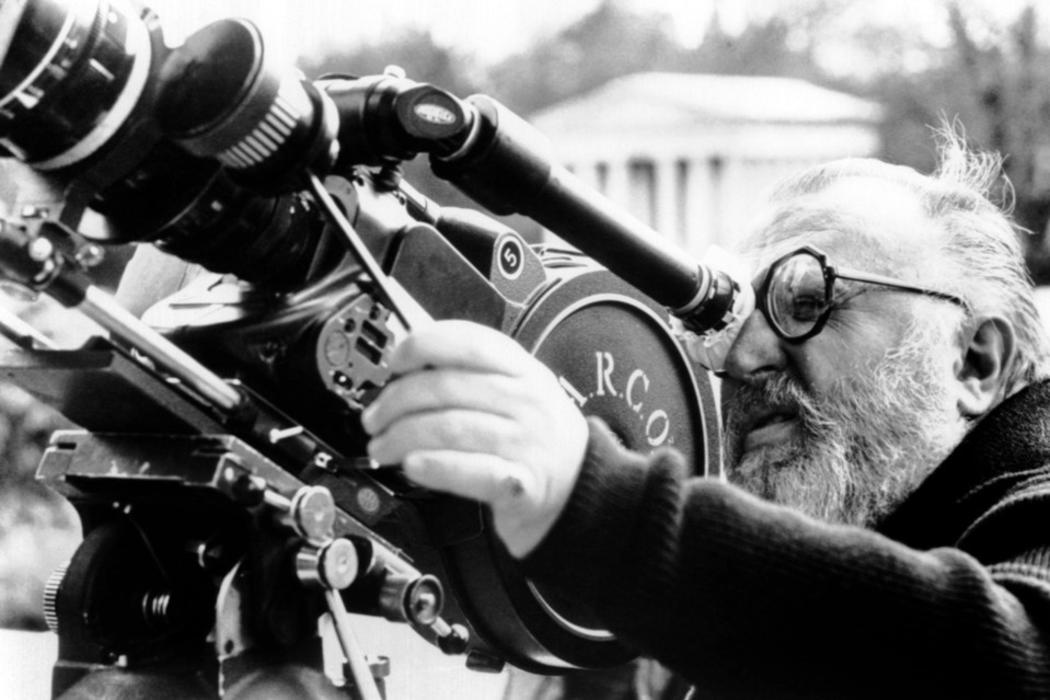

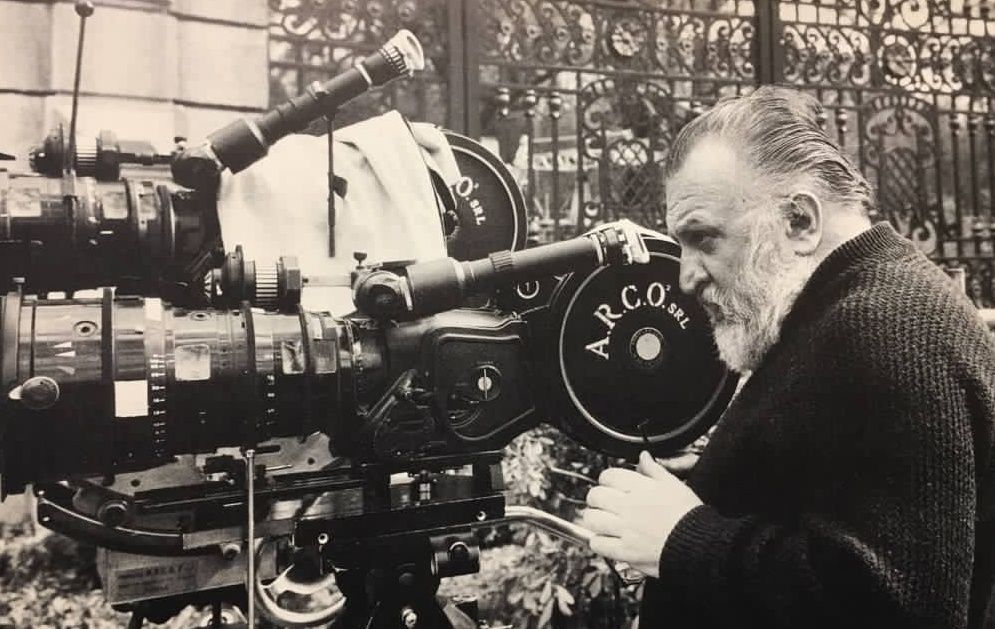

TONINO DELLI COLLI, AIC

Director of cinematography for three major films of Leone—The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Once Upon a Time in the West and Once Upon a Time in America. Born in Rome on 20 November 1922, he began working at Cinecittà as a teenager in 1938. He began working as a film cameraman in the mid-1940s and in 1952 was the first Italian cinematographer to make a colour film, Totò a colori. He became a master of his art at home and abroad. He created the lighting for Pasolini’s films from 1961 on, and until 1976 worked with directors Louis Malle, Roman Polanski and Jean-Jacques Annaud. He was also chief cinematographer for the last three films of Federico Fellini. He never retired and died of a heart attack in Rome on 16 August 2005.

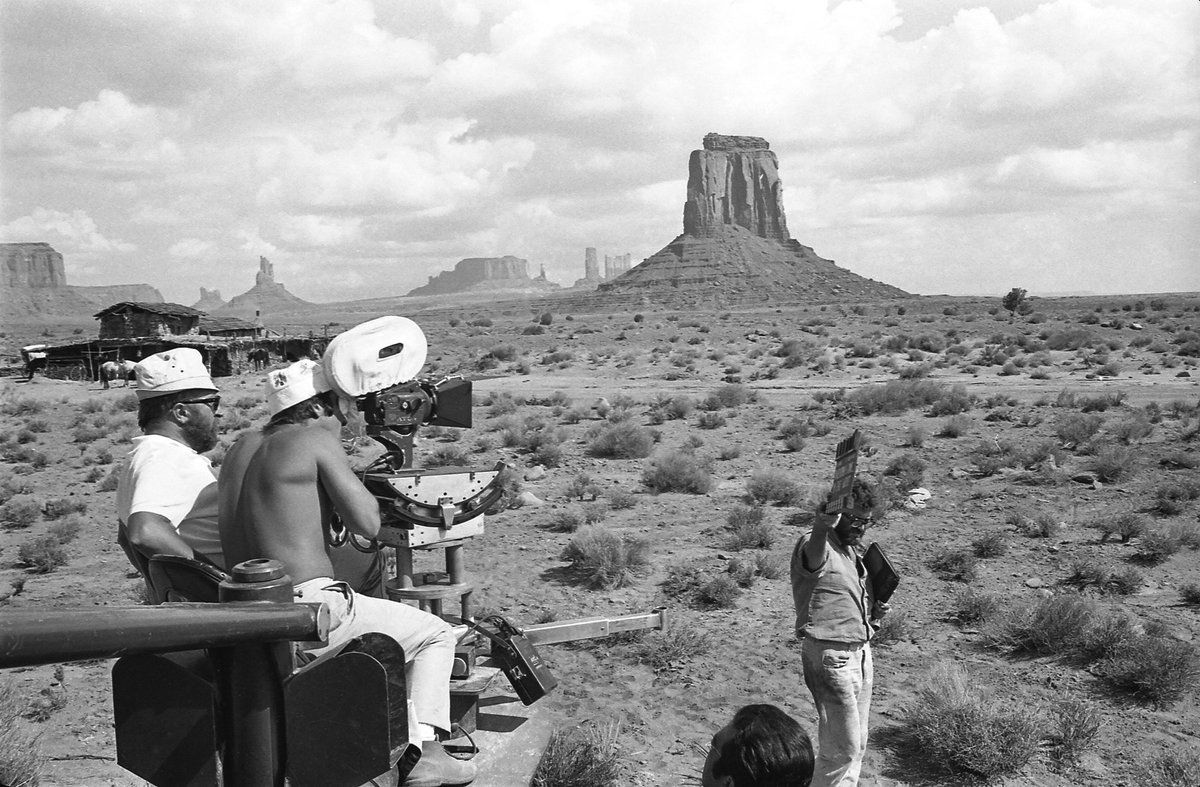

In the 1960s, Delli Colli began his working relationship with Sergio Leone, a collaboration that would bring him his greatest fame in the United States. Leone and Delli Colli reimagined the Westerns of John Ford and Howard Hawks, taking genre films to the level of art through glacial but tense pacing; innovative sound design; fresh, minimalist dialogue; and, above all, obsessive and almost exclusive use of extreme close-ups and very wide shots. The results were dubbed “spaghetti Westerns.” The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) was reportedly made for $250,000 and was a box-office blockbuster. Once Upon a Time in the West (1968) had a bigger budget, and Henry Fonda was cast against type as a ruthless villain.

“Sergio was a skinny kid who was working as an assistant to Bonnard,” recalls Delli Colli. “After Bonnard died, Sergio finished the shooting of The Last Days of Pompeii, and then directed The Colossus of Rhodes. Sergio came to Spain, where I was making a [Luis García] Berlanga film called El Verdugo [The Executioner, also known as Not on Your Life] with Nino Manfredi. It was 1963, and he was looking for money from our producer, the former goalie of the Real Madrid [soccer team], who in turn was being financed by a pharmaceutical company. He had the idea of making a film about the eagles of Rome, but there wasn’t a cent to be had.

“Back in Rome one night, Sergio took me to see Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. He told me it was a good idea for a low-budget Western. That was true, because all the action took place in one little town, and little towns like that were still around in Spain. So I helped him find the producer, but I had no plans to make the film myself because I couldn’t work for nothing.”

Later, Delli Colli heard that there were near riots at Rome’s Supercinema because crowds were trying to get in to see A Fistful of Dollars (1964). The surprise international hit kick-started Leone’s career. “Sergio was a real go-getter, a very meticulous artist who paid attention to everything he did, right down to the smallest details,” says Delli Colli. “For the images, he asked for things that were truly effective: full light for long shots because he wanted the details to be visible on screens of all sizes, and close-ups with the individual hairs of the characters’ beards visible. It was impossible in Spain—he wanted deep, long shadows, the deepest and longest we could get, and the [sun went] down late. On the set, we prepared in the morning, and then we just died waiting for the right light. I did everything I could to accommodate him within the limits of what was possible. And then there were the details! He wanted to shoot the actors’ eyes in every scene. I told him we could shoot 100 meters of eyes—looking here, looking there—and then use them whenever he wanted. But he wasn’t having any of that. And that’s how it went for the entire shoot. But his three-hour films pass quickly [when you watch them]. A three-hour film made today is a chore to sit through.”

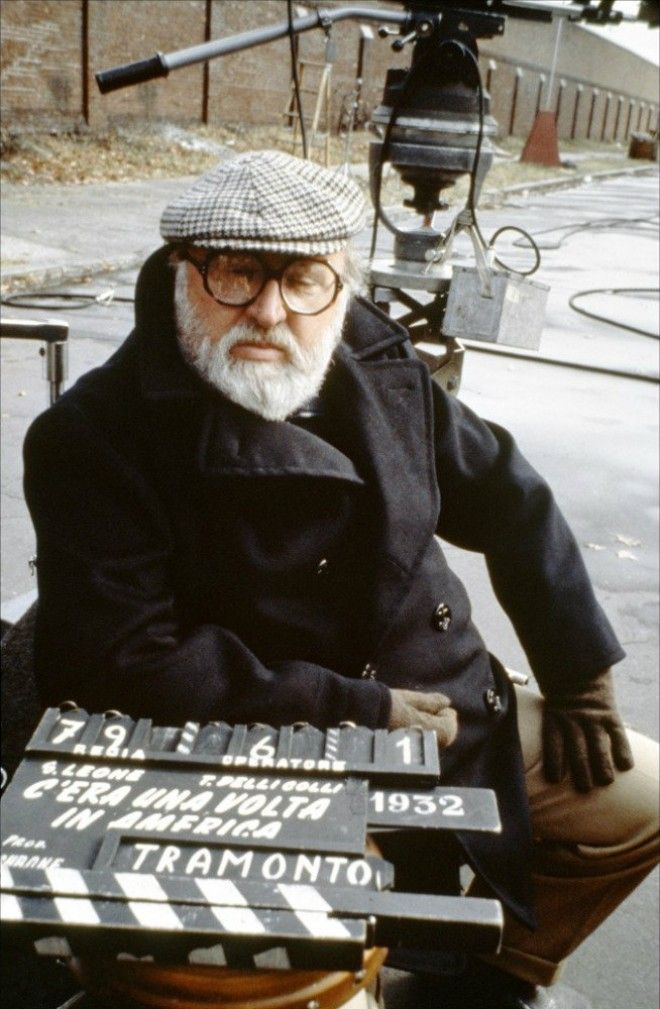

Delli Colli’s collaboration with Leone reached its apogee with Once Upon a Time in America (1984), a sweeping gangster epic that earned acclaim at Cannes but was radically cut down in the editing room by its U.S. distributor. Leone’s original cut received a few special screenings in the States and only recently became available on home video. “Once Upon a Time in America was a long film because there were a lot of interruptions [during production], thanks to Sergio’s meticulousness and his desire to make a film that would be unique in its genre,” says Delli Colli. “First, we couldn’t find the right actors because he had specific types in mind, but we kept looking. Even though he couldn’t speak a single word of English, he was able to make himself understood by using French, always with a smile on his lips. The American actors loved working with him. The interiors were shot in Rome, at the De Paolis Studios, and the exteriors were shot in a Puerto Rican neighborhood in New York. It was the sets that inspired my choices in terms of the cinematography. The story is a complex one, but when you see the film, you understand that it was worth the trouble. It displays all of Sergio’s artistry.” —Tonino Delli Colli, AIC, American Cinematographer (A Lifetime Through the Lens)

SERGIO LEONE: THE WAY I SEE THINGS

Western towns controlled by outlaws. Cigar-chewing heroes in looming close-ups. Operatic showdowns. Throbbing music. Movie buffs know the trademark elements of the great Italian filmmaker, Sergio Leone, by heart, but the engaging documentary Sergio Leone: The Way I See Things will surely give even the most ardent fan new insights into this unique master. The maestro behind such genre epics as A Fistful of Dollars, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West, Leone (1929-1989) was a superb stylist who took the American Westerns he loved as a kid and transformed them into visual arias all of his own, in the process influencing such directors as Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez. Just as fascinating as his films, Leone’s larger-than-life personality is profiled here in an illuminating journey, rich in both anecdotes and gorgeous clips from his movies. By examining Leone’s superb use of image, sound and the frame, the film reveals the magic and the rough beauty of his arid vistas and outsized characters. Actors Eli Wallach and Claudia Cardinale, directors Giuliano Montaldo and Vittorio Giacci and historian Christopher Frayling, among others, offer invaluable contributions to Giulio Reale’s exhilarating Sergio Leone: The Way I See I Things, a mesmerizing portrait that makes us look at an old master with fresh eyes. —Fernando F. Croce

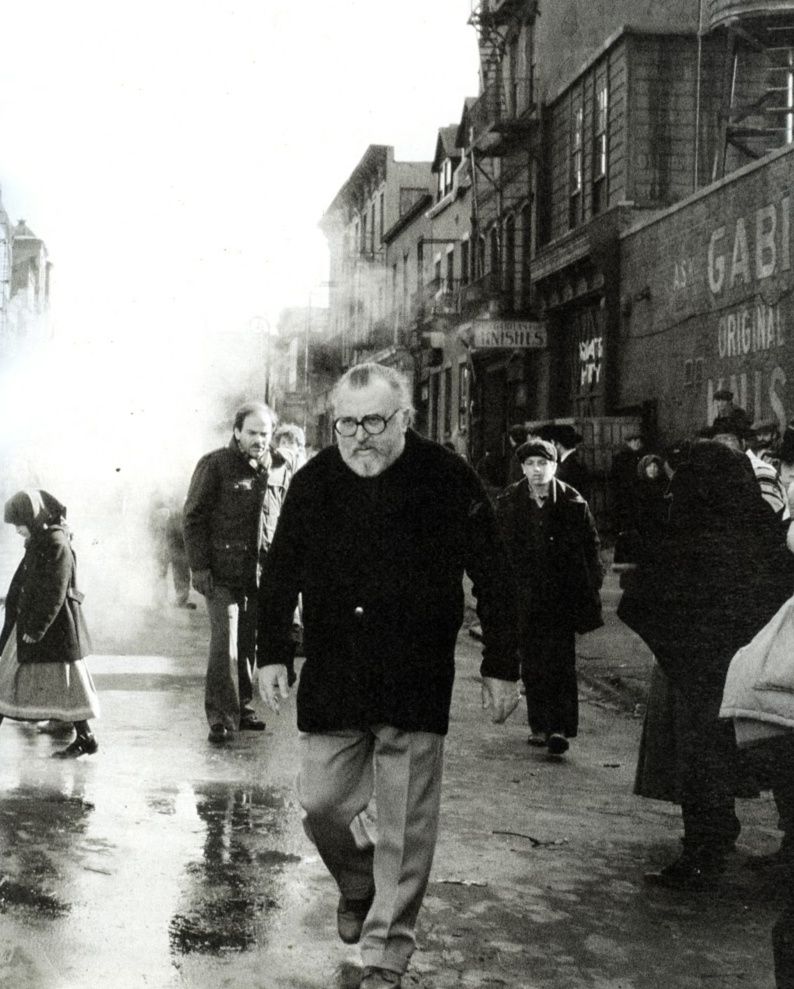

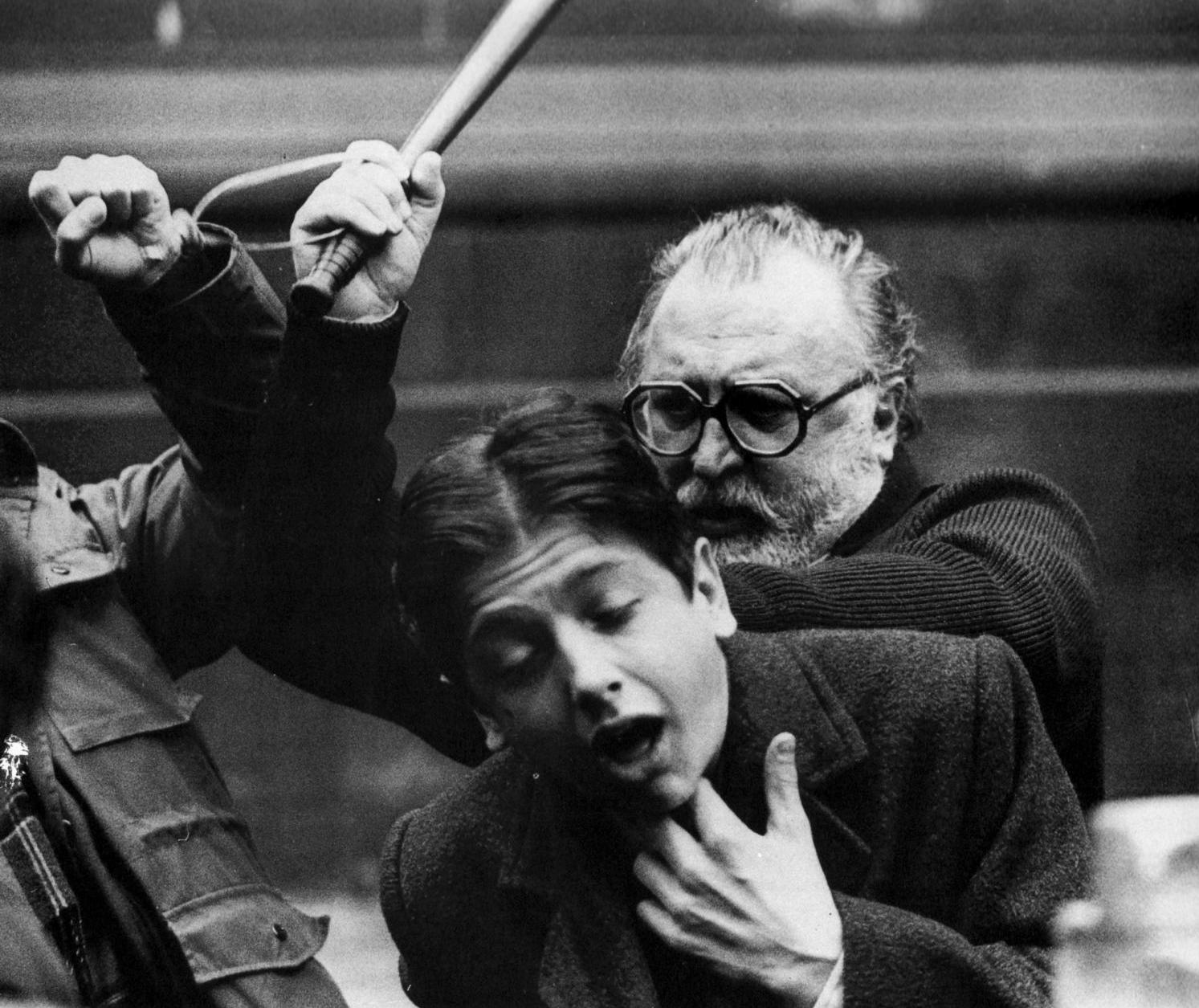

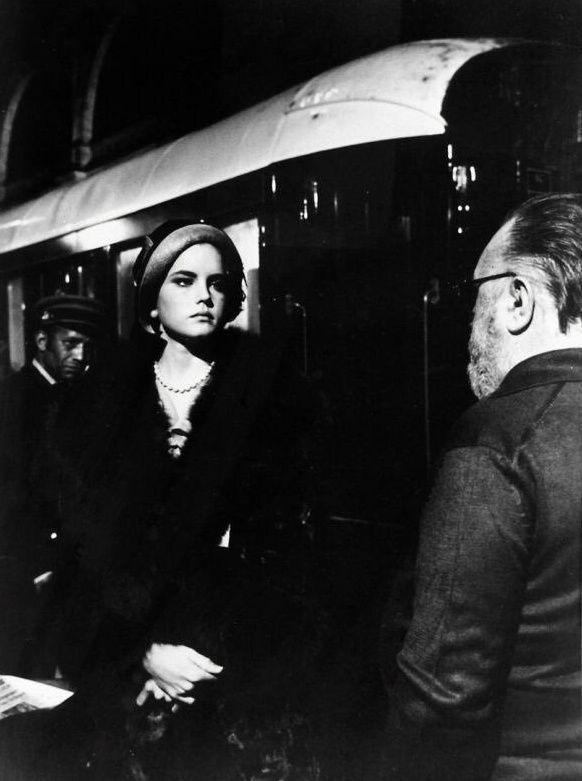

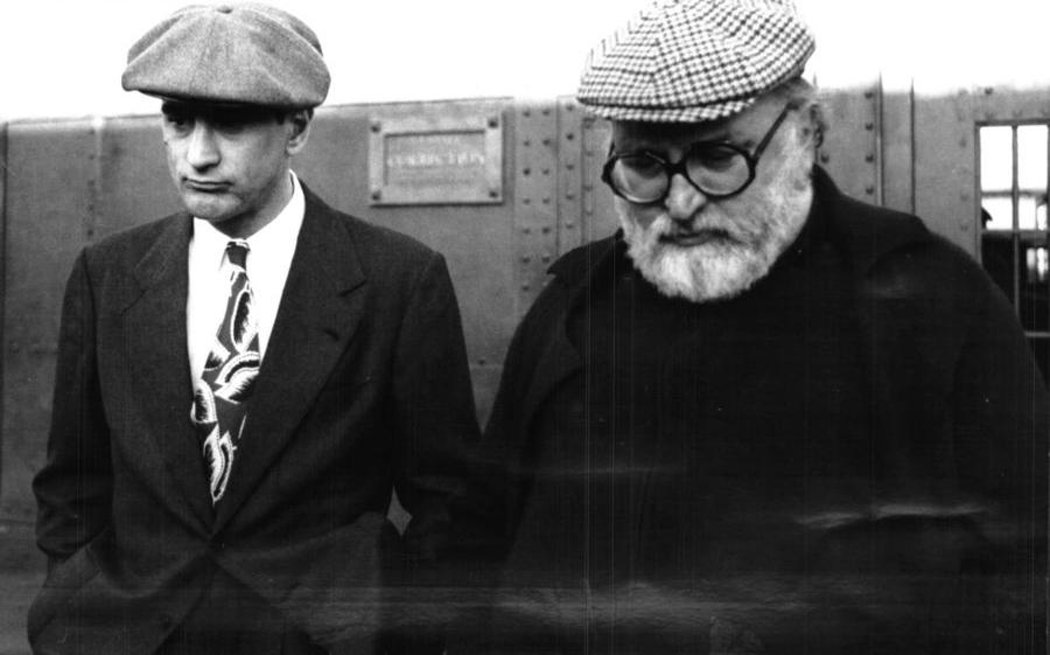

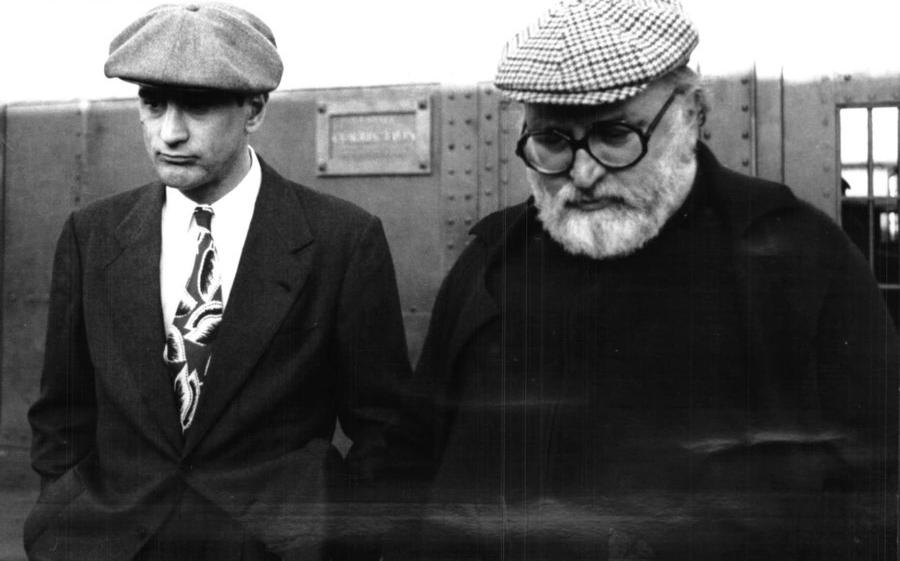

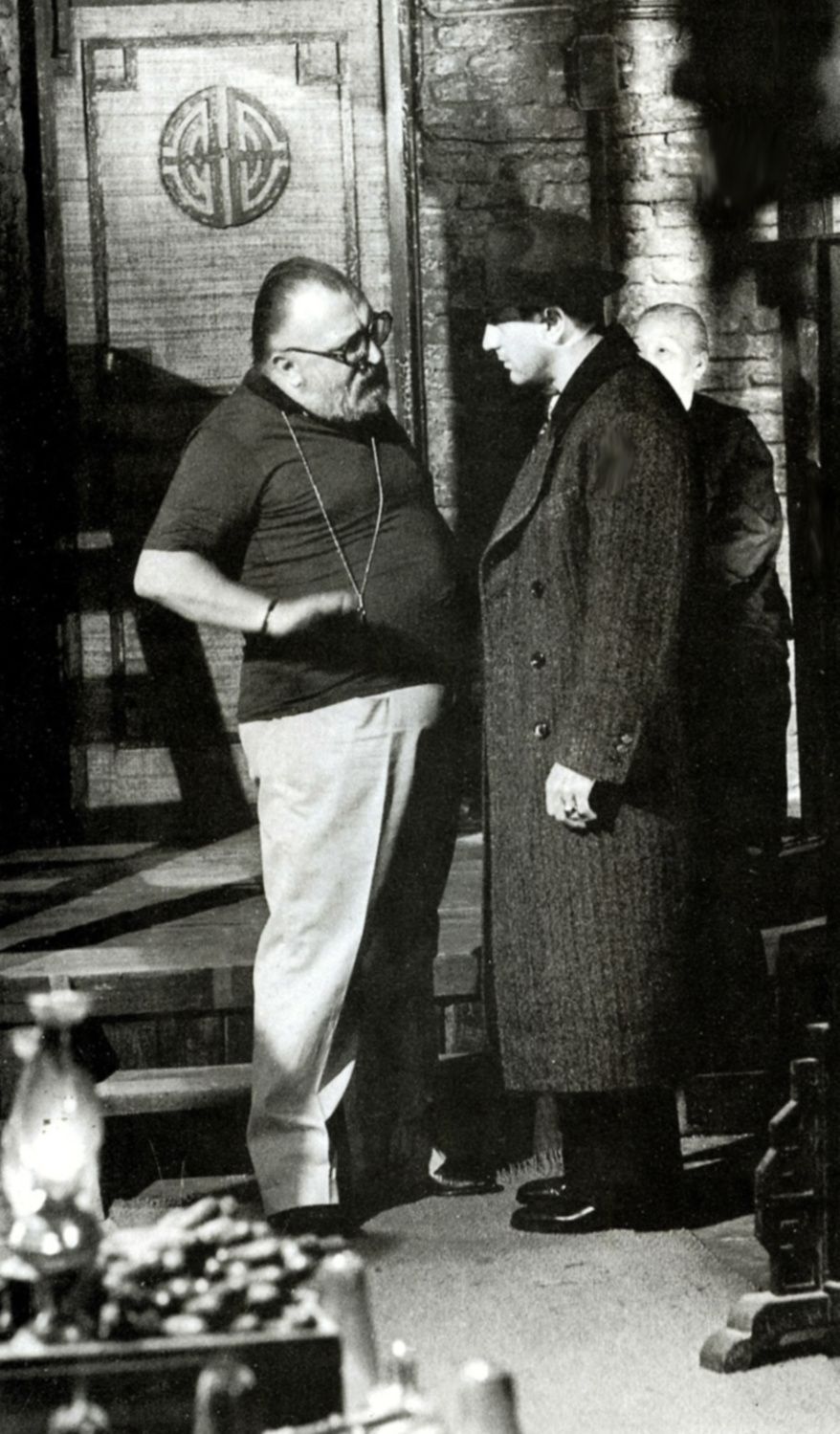

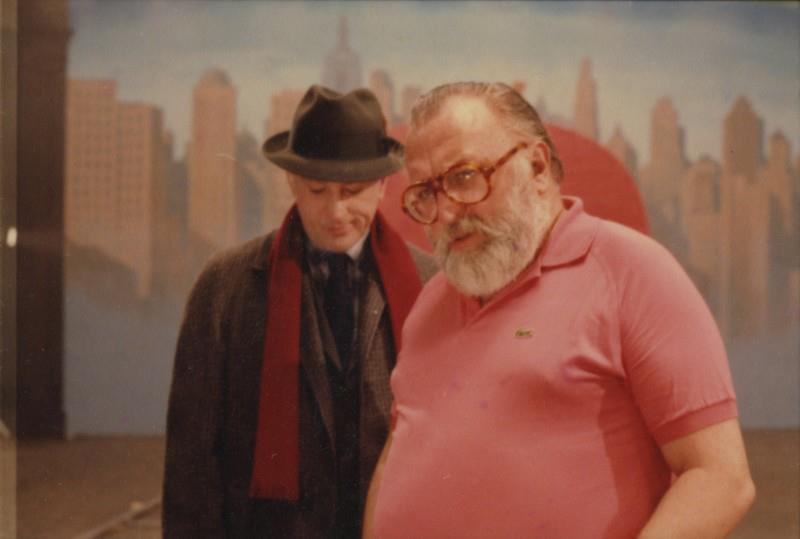

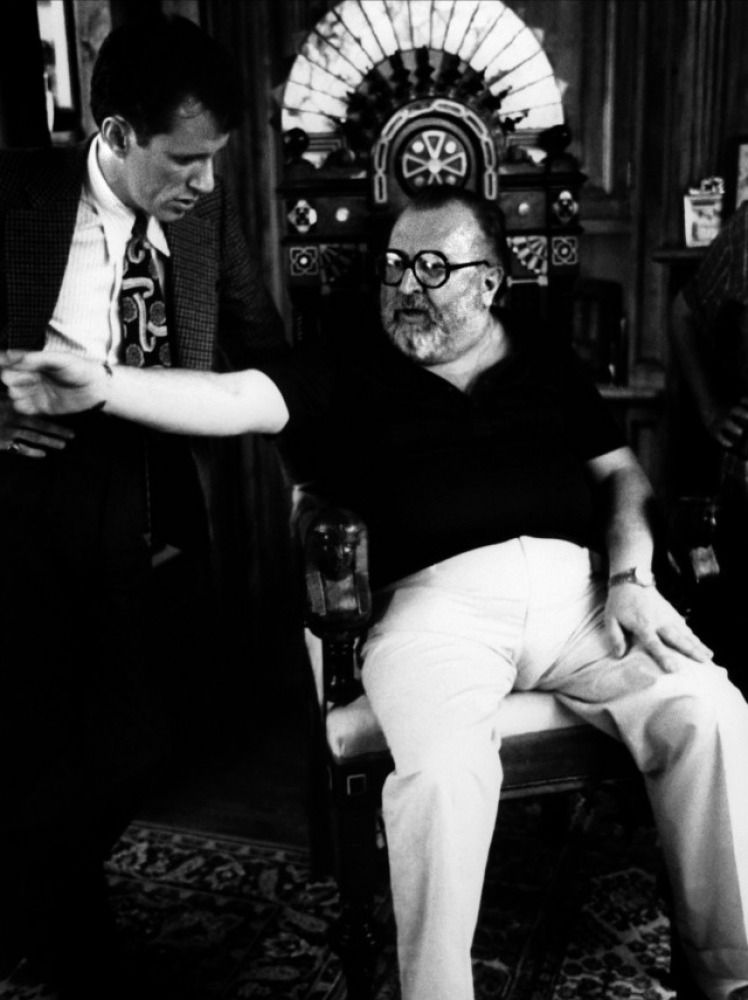

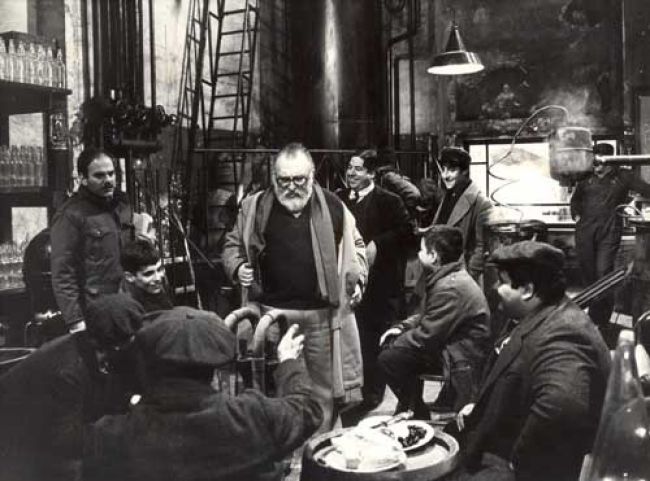

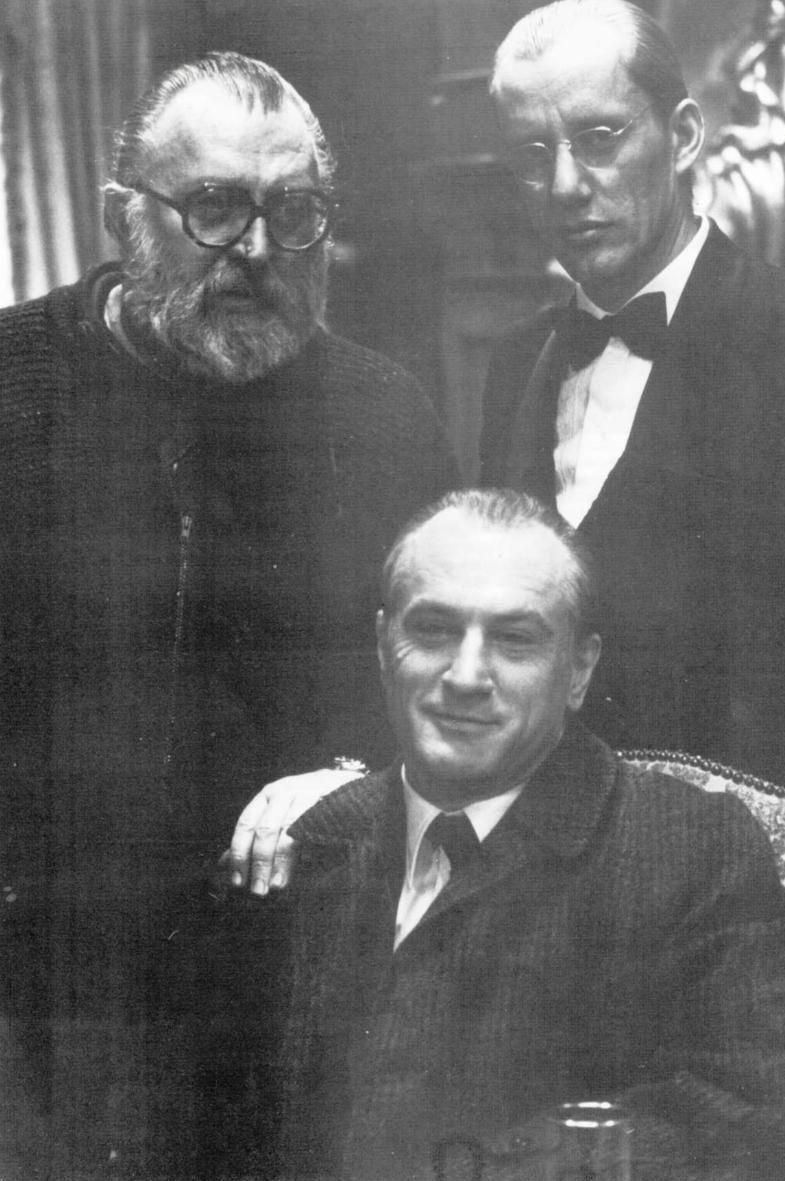

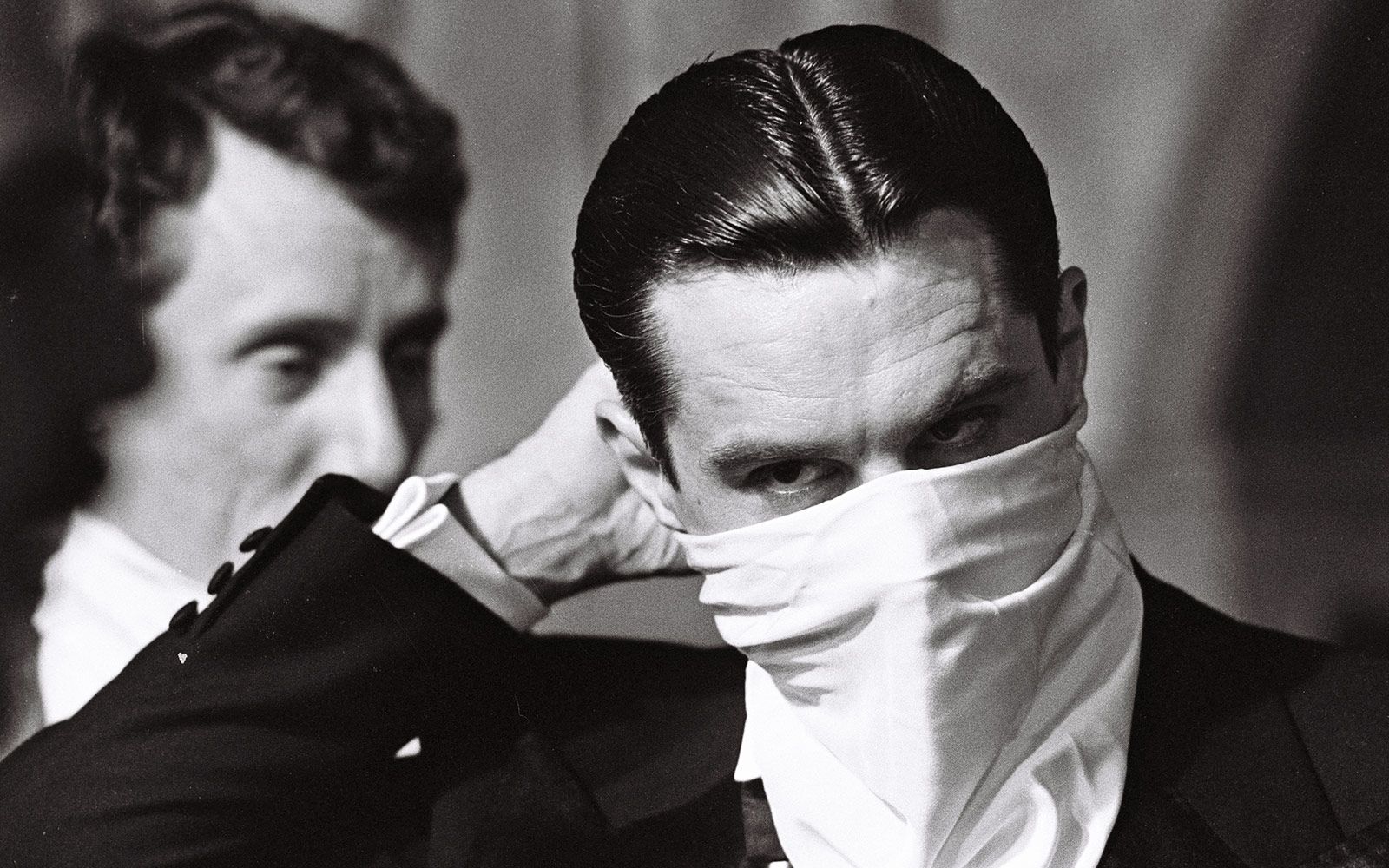

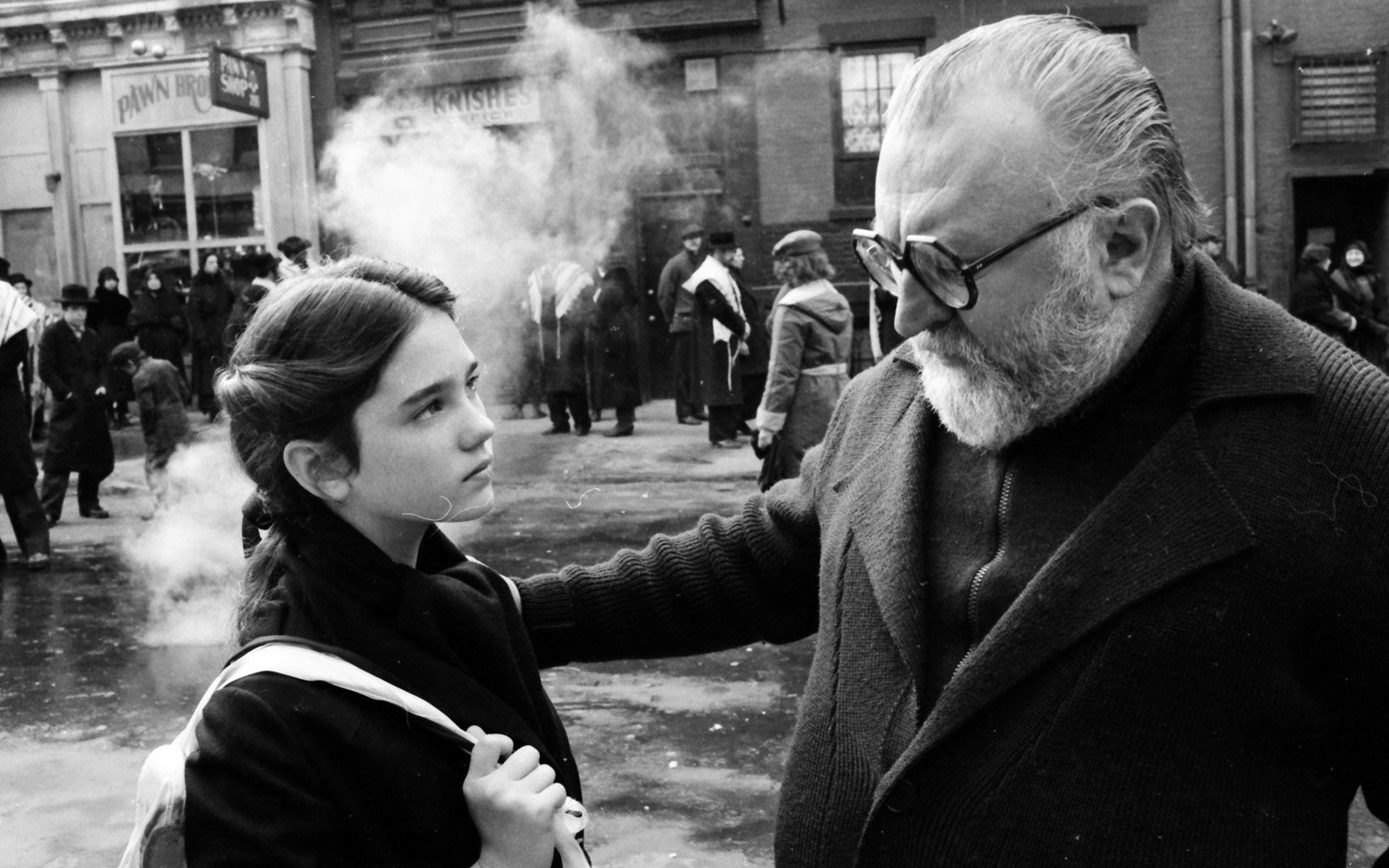

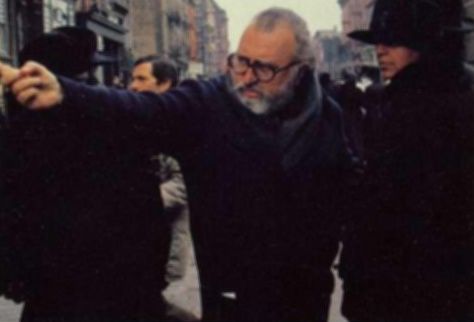

Here are several photos taken behind-the-scenes during production of Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America. Photographed by Angelo Novi © The Ladd Company, Embassy International Pictures, Producers Sales Organization, Warner Bros. Intended for editorial use only. All material for educational and noncommercial purposes only.

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or donate directly below: