By Jasun Horsley

An alternate and more autobiographical version of this essay first appeared in Seen & Not Seen: Confessions of a Movie Autist.

Saint Clint Vs. General Kael

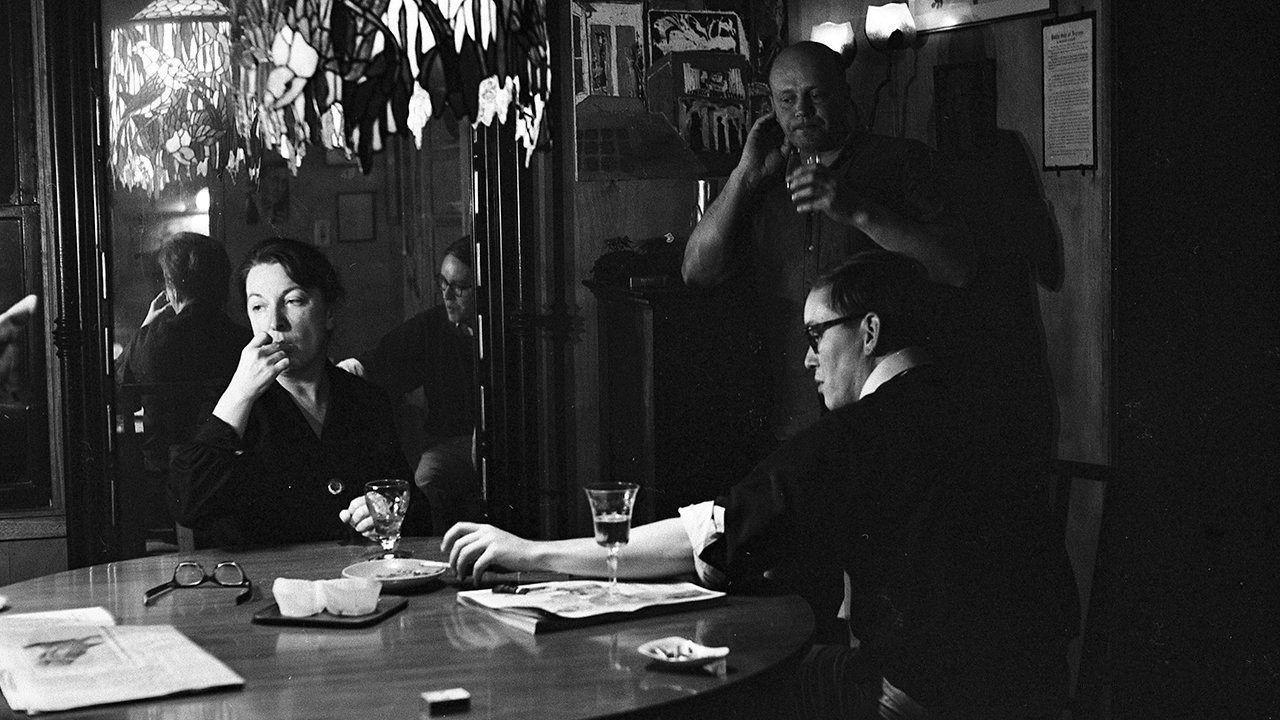

“A lot of people thought [Pauline] was really turned on by Clint Eastwood. He was the big, macho, alpha male, and Pauline just loved beating up on him. And I think there were reasons why she loved beating up on him.”

—Ray Sawhill, to Brian Kellow

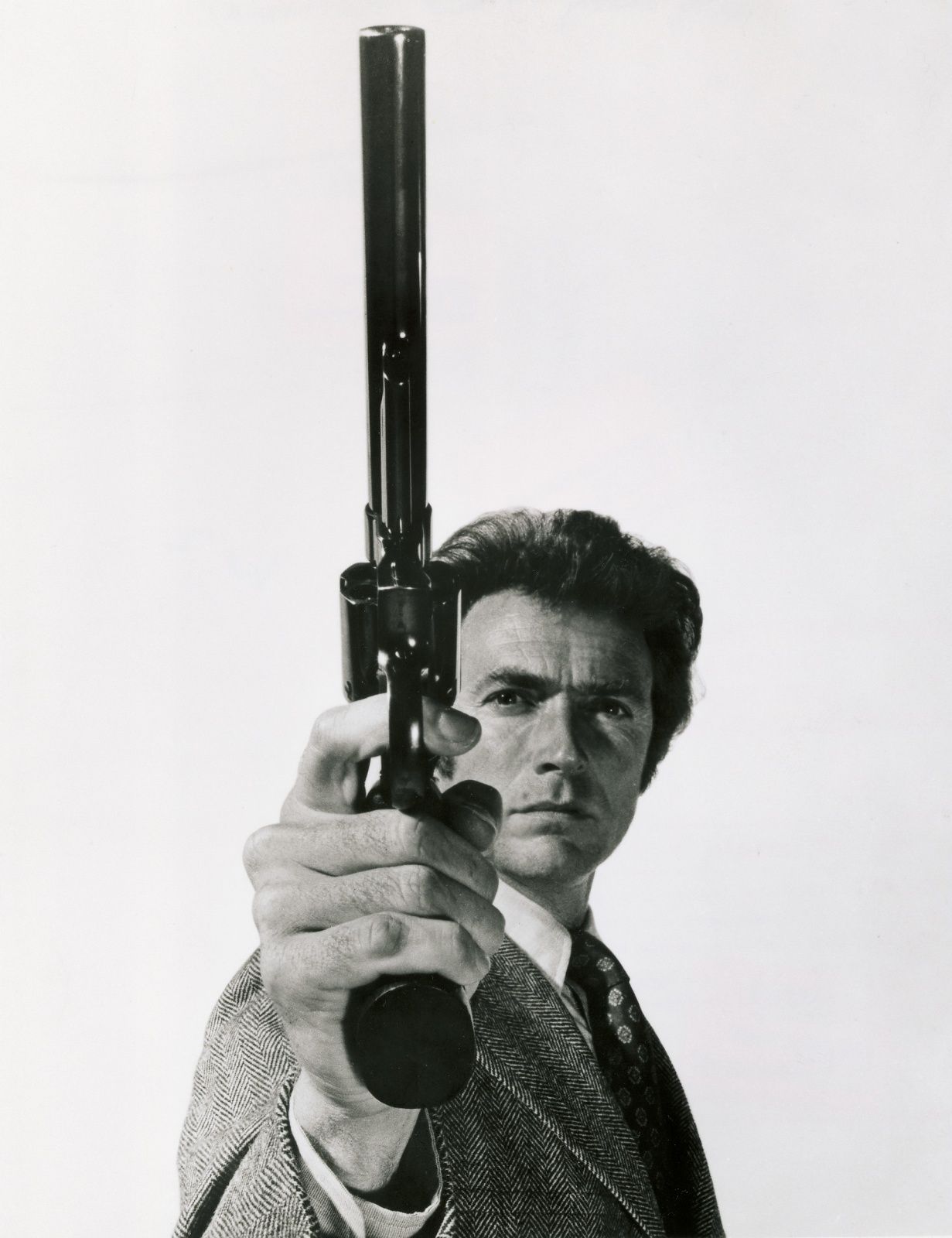

When I was twelve—and caught up in the terrifying disorientation of adolescence—I discovered Clint Eastwood, and it was through the portal of that one, all-consuming focus that I became the movie autist I am today. As a teenager, just looking at images of Clint gave me a kind of dreamy bliss. It was a strange kind of love: I didn’t desire him, I wanted to disappear into him, to become him. I identified with Clint Eastwood because he was everything I wasn’t at that time: tough, cool, ruthless, efficient, in control; he was his own man. The politics of it never occurred to me—at least until I read Pauline Kael, but even then I didn’t really care. I intuited, rightly I think, that Eastwood’s appeal went beyond politics. It was primal, which is exactly what made it so appealing, and so dangerous.

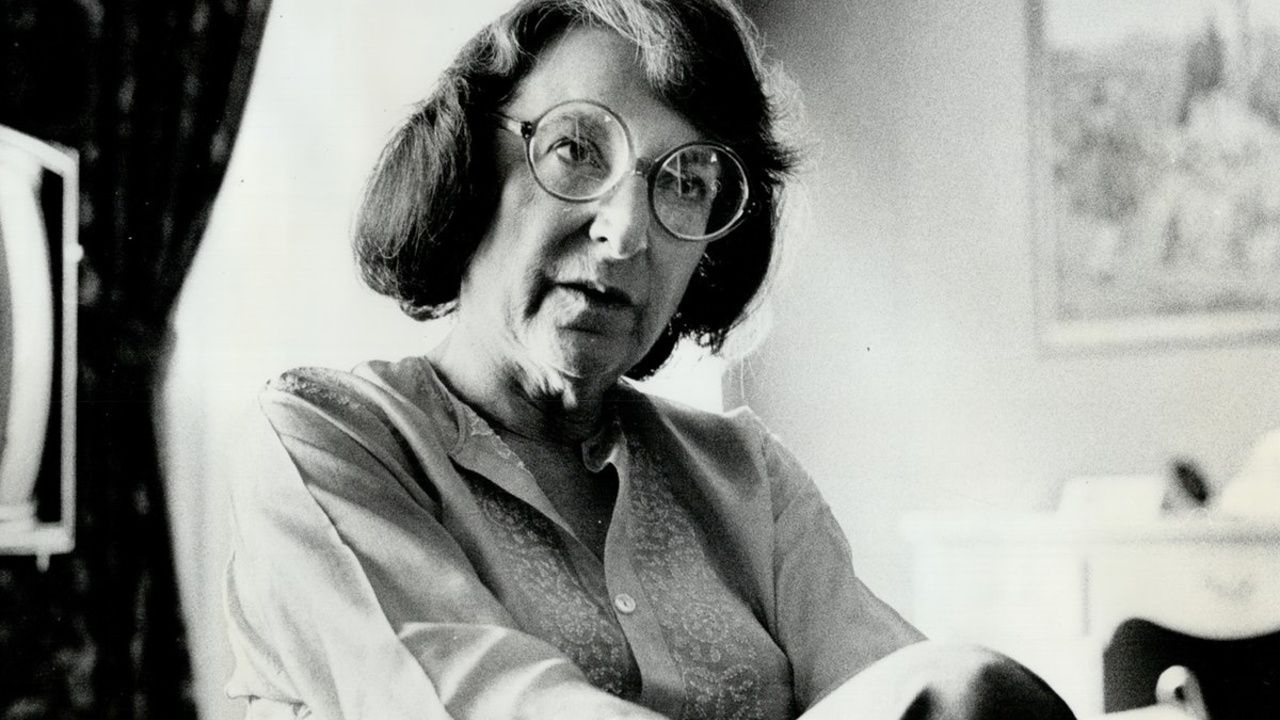

Even so, discovering Kael a year or so after I fell in love with Eastwood, and immersing myself in her writings, undoubtedly leavened my responses to Clint. I adored both of them, and yet neither had a kind word to say about the other. It was as if this archetypal divide in the movie sphere reflected a primal split within my own psyche.

The acrimonious relationship between Clint Eastwood and Kael was a real-life drama I had no idea about at the time. Except that I did, really, because it’s right there in Kael’s reviews of Dirty Harry, Magnum Force, and The Enforcer, in Deeper Into Movies, Reeling, and When the Lights Go Down respectively, all of which I read at roughly the same time (and maybe even before) I first saw those movies.

At some point or another—maybe while reading all the Eastwood bios I could get my hands on—I heard that Eastwood had responded publically to Kael’s description of Dirty Harry as “fascism medievalism” (in “Saint Cop”), insisting it didn’t bother him because he knew she was “full of shit.” That was pretty much the extent of my awareness of the ongoing feud between them at that time. It’s likely that knowing these two major movie influences were so far from seeing eye to eye made an impression on me anyway. It was a bit like being raised by parents who badmouth each other any chance they get and act out their animosity in front of the kids: it’s going to lead to divided loyalties. And not only in me. There is quite a bit of frisson around the whole Kael-Eastwood debate on the Internet: people who hate Kael and love Eastwood, and vice versa, or who see one or the other as wildly overrated and use the Eastwood-Kael controversy as proof. I have always been drawn to the challenge of reconciling seemingly irreconcilable differences; maybe this is where that “calling” first started to become conscious in me?

A couple of years ago, reading Kellow’s Kael bio and a small book by Paul Nelson, Conversations with Clint Eastwood, I found out how deep the animosity between them went. At one point in the book, Eastwood and Nelson are bitching about Kael and Eastwood says,

She’s really suckered them into thinking she knows something. That’s what’s so funny. It becomes a kind of a joke. Just making a lot of outrageous statements not having any bearing on anything, but you’re doing them because you’ve found that that’s the avenue to get attention. That’s exactly what the secret to Kael is: she’s found a way to get attention. [Emphasis added; I noticed also the way Eastwood changed pronouns, from “she” to “you,” as if imagining Kael was right there with him.]

That’s Clint’s version in a nutshell. And while it may seem improbable to anyone who has seriously followed Kael’s work, it’s true enough that she got Eastwood’s attention, and maybe that’s what Clint is implying. If so, there may be something in that, too. Symmetrically enough, when Kael was asked about Eastwood’s steadily growing reputation in a 1994 New Yorker interview (three years after she retired), she saw it as a “delicious joke—further proof that there’s no such thing as objective judgment in the arts.” What does it mean when two movie powerhouses try to publicly reduce each other to a joke? Turning someone into a joke is a way to strip them of their power, to reduce them to buffoons. It’s an offensive-defensive strategy, probably sparked by a fear of being powerless oneself: something in the other presents an inexplicable threat, and has to be reduced by whatever means necessary.

In a footnote in the Nelson book, there’s a quote from Sondra Locke’s autobiography which states that, after Kael’s review of The Enforcer, Eastwood asked a psychiatrist to do an analysis of Kael based on her reviews of his movies. According to Locke, Eastwood claimed that the psychiatrist’s conclusion was that Kael was sexually attracted to Eastwood. Locke writes that Eastwood also claimed Kael had called him to apologize for her reviews, but then later admitted he’d made the story up!

Earmarks of an obsession? If it sounds from Locke’s account more like Eastwood was inexplicably attracted to Kael, it pays to remember that such dangerous attractions (as seen in Play Misty for Me and The Beguiled, two of Clint’s movies which Kael declined to review, or even mention) usually go both ways. The anecdote certainly betrays Eastwood’s own bias: apparently any woman who was trying to get (his) attention could only want to get fucked. This plays out in an overt—and overtly macho— form in High Plains Drifter, Clint’s first film as a director after the woman-fearing fantasy of Misty. A character played by Marianne Hill insults Eastwood’s Stranger on the street, insinuating that he’s less than a man in what is a very obvious “come on.” His response: “If you want to get acquainted, why don’t you just say so?” before dragging her off to the barn and raping her. And of course, she likes it.

Do You Love Me?

In fact, Kael’s appreciation of Eastwood’s physical attributes was evident from the very start, in the notorious Dirty Harry review which ignited the feud. In the second paragraph of “Saint Cop,” Kael describes “soft-spoken Clint Eastwood—six feet four of lean, tough saint, blue-eyed and shaggy-haired, with a rugged, creased, careworn face that occasionally breaks into a mischief-filled Shirley MacLaine grin.”

A few weeks before the Dirty Harry review, in “Notes on New Actors, New Movies,” Kael acknowledged her susceptibility to the kind of “male fascism that makes an actor like Robert Redford or Jack Nicholson dangerous and hence attractive” (emphasis added). Apparently Clint’s shrink was onto something. If so, it didn’t do much to assuage Eastwood’s righteous indignation. In a 1996 “authorized biography” (read: hagiography) of Clint Eastwood, Richard Schickel claimed that Kael’s review of Dirty Harry continued to haunt Eastwood throughout his career. Eastwood even asked Schickel if he’d happened to see an interview in which Kael said that one of her regrets about retirement was that she no longer had a forum in which to criticize Clint Eastwood. “Can you imagine that kind of bigotry?” Eastwood demands of Schickel.

Kael was unusually relentless in her disdain for Eastwood. Besides Dirty Harry, she conspicuously reviewed only his worst films, staying away from ones which—I would guess—she wouldn’t be able to excoriate to quite the same degree (Coogan’s Bluff, The Beguiled, Thunderbolt and Lightfoot, The Outlaw Josey Wales, Escape from Alcatraz, or Bronco Billy). It’s also undeniable that Eastwood’s performance in A Fistful of Dollars was a kind of breakthrough, and that fifty years later it still stands up as a matchless piece of stylized acting, and as the birth of one of the most enduring characters in movie history. Kael had kind words to say about almost every major male star of the period—not just Beatty, Redford and Newman but James Caan, Steve McQueen, Lee Marvin, Burt Reynolds, even Charles Bronson (who she compared to Christ) and Ryan O’Neal!. Yet Eastwood was nothing but a “tall, cold cod”? (Admittedly, she didn’t lose any love on John Wayne.) There does appear to be something besides simple faulty judgment at play here.

Even if Kael was insincere in her disdain for Eastwood (she seemed to view baiting him as a kind of sport—or maybe schoolyard flirting?), bigotry is still a strong word for an actor to use for a critic’s dislike of him. And in 1996, Eastwood was a fully established film legend with all the critical endorsements (and Oscars) anyone could ever wish for (or dream of) to feel secure in their legendariness. A more pertinent question for him to have asked might have been: why did he still care so much?

*

As is invariably the case with rabbit holes, the deeper I went into this “movie,” the darker it got. While I was searching the Internet for clues, I found the following passage:

There’s a scene in the final Dirty Harry movie, The Dead Pool [1988], in which a female film critic is brutally slain. Clint was thinking of Pauline Kael, his harshest critic… The critic in this film is made up to resemble Kael as she appeared during this film’s release as an in-joke.

I downloaded the movie—it’s the worst of the Dirty Harry series, all-but unwatchable—and watched the scene. The middle-aged, large-nosed, dark-haired, and diminutive film critic Molly Fisher is writing at her desk in a nightgown when she hears a sound. She gets up and closes the sliding doors. A masked killer grabs her from behind and holds a knife at her throat. “Do you ever notice how time seems to slow down at night?” he says. “Just like in my films—a dream world.”

In Kael’s review of Magnum Force, “Killing Time,” she referred to Eastwood as “the hero of a totally nihilistic dream world.” And there’s more. The masked killer in The Dead Pool is pretending to be (or deluded into believing he is) a film director whose violent fantasies Fisher has panned in her reviews. Fisher pleads with him by mentioning her heart. “A critic with a heart,” says the killer, “that’s a laugh.” He then drags her over to the couch and throws her down, as if to rape her. He wants to know if she likes his films but she doesn’t know who he is. “What kind of a film critic are you?” he snaps, then lists several films for her so she can identify him. “What do you think of my films?” he demands. “Give me your honest opinion.” “I like them,” Fisher says weakly. The killer calls her a liar and thrusts the knife towards her. The film cuts to the next scene; it’s daylight and Harry arrives with his token oriental partner. The oriental makes a joke about the murder by giving it points out of ten, as if rating a movie. Dream worlds within dream worlds.

Did Kael know about Clint’s little “in-joke”? Hollywood’s a small town—or a small state of mind—so chances are she did. It was as if he was sending her a personalized message wrapped inside the envelope of his tawdry little movie. Ironically, and if nothing else, it would be a way of all-but compelling her to watch it! It’s a darkly occult anecdote, and it makes a pretty strong case for a Freudian analysis of Eastwood’s Kael-obsession. Now I think about it, what was the famously prosaic, anti-analytic Eastwood doing in therapy anyway? In a showdown between Dirty Harry and Dr. Freud, who’s going to walk away with his armor intact?

“Sometimes, doc, a gun is just a gun!” (Blam!!)

Mother-Father Issues

“All of us have probably had the feeling of being divided between what we got from our mother and what we got from our father, and no doubt some of us feel that we’ve gone through life trying to please each of them and never fully succeeding because we have always been torn between them.”

—Pauline Kael, When the Lights Go Down (review of James Toback’s Fingers)

Returning to Kael’s own possible father-fixation on Saint Clint: apparently Eastwood not only missed the subtler allusions she made in 1972, but also the above-quoted 1994 interview, in which Kael made probably her first and last concession, both to Eastwood’s acting and his sex appeal:

I did think Eastwood’s performance in In the Line of Fire was one of the best he’s ever given, perhaps the best. But when he was fun in his early movies it wasn’t because of his acting skill, and now that he has a little skill he’s lost the spaghetti sexiness that made him fun. He’s all sinews. He has become a favorite of intellectuals just when he’s losing his mass audience. It has to be a consolation prize.

Kael calling Eastwood “fun” is a very far cry from her more-quoted descriptions of Eastwood as a “cold cod.” In light of those more famous reviews, it’s a perhaps striking case of dishonesty in her writing. If Kael really found Eastwood sexy and fun, why didn’t she say so? Why did she imply the reverse? And, on the other side of the spaghetti stand-off, in light of their decades-long feud, why wasn’t Kael’s admission that she enjoyed Eastwood’s “spaghetti sexiness” received by him as the olive branch it clearly was? Was it because it only rubbed salt in the wound? Wasn’t it just like a woman to admit she had found him sexy, all those years ago, now it was too late for him to do anything about it?

*

At the risk of getting overly Freudian about this: The picture which all this paints is of an all-powerful male icon reduced to an angry, petulant child by the continued disapproval/rejection of a mother/anima figure immune to all his charms. On the other side of the rift, there’s a hugely influential female critic showing a seemingly disproportionate hostility towards a soft-spoken, saintly, masculine hero/father/animus figure. Mom, meet Dad. These sorts of unconscious psychodramas (even when as impersonal and long distance as this) are invariably symmetrically arranged. If Kael somehow unwittingly acted as a receptacle for Eastwood’s mother issues, then Eastwood would have inevitably been a close match for Kael’s unresolved “father stuff.”

In his movie roles, Eastwood is pretty much indifferent to female charms (there are a few exceptions, but he mostly regrets it). In his public life, he was as contemptuous of Kael as she was of him—though who started the playground bickering remains unclear, even after all these years. Also, Eastwood’s career wasn’t in any way damaged by her attacks; it may even, as Schickel suggests, have been boosted by them. It’s likely that this—evidence of her powerlessness as a critic—would have rankled Kael, even as her derision of Eastwood’s acting skills and her suggestion that he was an unwitting dupe for Nixonite agendas would have wounded Clint’s pride. (Actually, Eastwood was buddying up to Nixon at that time, and eventually he did go into politics, though strictly local.) Apparently they were triggering each other’s power issues—and power issues for grown-ups invariably come down to “sex,” though also, at a more superficial level, money, status, and influence.

Kael was an anti-moral moralist; she despised message movies and famously wrote, “If there is any test that can be applied to movies, it’s that the good ones never make you feel virtuous.” Yet there were movies that incited her wrath and indignation, and Clint Eastwood’s were most frequently in the line of her fire. I find it especially suggestive that, in her closing remarks in “Saint Cop,” she describes a scene which she supposedly witnessed while leaving the theater: a little girl telling her father, “That was a good picture.” Kael doesn’t include the father’s response (I’d love to know what it was); she merely offers it up as an implicit, dire warning that this “almost perfect piece of propaganda for para-legal police power” (a rare case of Kael alliterating for impact) had achieved its aim, and colonized the consciousness of an innocent.

If the little girl was a point of identification (a stand-in) for Kael, both as a daughter and a mother, I suspect such parental concern was preeminent in her disdain for Eastwood’s pictures, that it fueled her conviction that his saintly killers were unsuitable as ideals for the young, male or female. There are all kinds of nuance to this. I was using Eastwood as a role model, and I couldn’t have helped but pick up on Kael’s disapproval of my choice. At the same time, even her indignation is strangely ambivalent: Kael betrayed her attraction to Eastwood not only implicitly in “Saint Cop,” but also explicitly in the first and perhaps last words she said publically about him. Separate the threads of ambivalence and what’s revealed is something like Kael’s disappointment with a strong male figure who proved unworthy of her hopes or expectations. Paging Dr. Freud.

It’s telling also that Kael stopped having serious romantic relationships around the time she began reviewing films at The New Yorker. But that’s a can of worms I will only tap lightly.

Western Dream Worlds

“Movies—a tawdry corrupt art for a tawdry corrupt world—fit the way we feel… Movies are our cheap and easy expression, the sullen art of displaced persons.”

—Pauline Kael, “Trash, Art, and the Movies”

In Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (“Saddle Sore”), Kael writes,

My father went to a western just about every night of his life that I remember. He didn’t care if it was a good one or a bad one or if he’d seen it before. He said it didn’t matter… The Old West was a dream landscape with simple masculine values; the code of the old Western heroes probably wouldn’t have much to say to audiences today. But the old stars, battling through stories that have lost their ritual meaning, are part of a new ritual that does have meaning. There’s nothing dreamy about it: these men have made themselves movie stars—which impresses audiences all over the world. The fact that they can draw audiences to a genre as empty as the contemporary Western is proof of their power. Writers and painters now act out their fantasies by becoming the superstars of their own movies (and of the mass media)… When it makes money, it’s not just their fantasy. The heroes nobody believes in—except as movies stars—are the result of a corrupted art form.

This was written in August of 1967. The three Leone-Eastwood Spaghetti Westerns were released in the US between in January, May, and December of that year, so at that precise time, Eastwood was in the middle of becoming internationally famous. Kael was writing not about Eastwood but about John Wayne, Robert Mitchum, and Kirk Douglas—the old Western stars who drew her father into the empty fantasy space of the movie theater. A point which Kael doesn’t make, but which I think is implicit in her account, is that her father chose to withdraw into Western fantasy rather than spend time with his family. “He said it didn’t matter.” The implication (for me at least, maybe I’m just cynical) was that it didn’t matter as long as it got him out of the house.

There’s further evidence for this reading—albeit circumstantial—in her review of Hud, in which she mentions her father several times. She describes “my father and older brothers charging over dirt roads… in Studebakers,” apparently a manly activity in which she wasn’t included. A few pages later she recounts a memory of her father “taking me along when he visited a local widow: I played in the new barn that was being constructed by workmen who seemed to take their orders from my father. At six or seven, I was very proud of my father for being the protector of widows.” She then admits that he was “adulterous,” comparing him to Paul Newman’s Hud, adding that he was “opposed to government interference” but “in no sense a social predator.” He was “generous and kind” she says, and “democratic.” She leaves out any clue as to how she felt when her child’s dream-view of her father as a “protector” was shattered by the adult realization of his adultery. And despite her kind words about him, the three incidents recounted all have a single theme: her own exclusion, as a little girl, from her father’s activities.

Kael’s father was a Polish, Jewish immigrant living in the West, running his own farm and in charge of Mexican workers. Probably another reason, consciously or not, he went to see a Western every night was because he was trying to learn about his new homeland, trying to figure out the proper “form.” John Wayne movies would have offered a kind of fantasy schooling on how to pass as an American. But whatever it was that pulled him or pushed him out of the home and into the movie theater—that displaced him—this dream landscape of cowboys, Studebakers, and adultery apparently took Kael’s father from her. Behind the dream was something not at all dreamy: the crass opportunism not just of philandering husbands but of movie stars exploiting the corrupted art form which created them.

No wonder Kael was so dedicated to saving the art form from corruption. And no wonder she felt such hostility towards a star like Eastwood—except there were no others like Eastwood; not for Kael, at any rate. He was her bete noir. He embodied that corruption the way the filmmakers tried to make “Hud” the embodiment of small-town evil—a cheap stunt which Kael rightly called them on. So why Eastwood, then, and not Wayne or the old time stars? The obvious answer is that Eastwood was on the ascent where Wayne was on the downward curve. Kael was after the biggest game in town.

Eastwood would go on to direct his own Western fantasies and to seize the Western crown from Wayne. Wayne himself was allegedly so disturbed by High Plains Drifter that he wrote Eastwood a letter, complaining that “the real West” was nothing like this, that it was full of good people (like Kael’s father?) who pulled together to tame the wilderness! Wayne would have been fully aware at that time (1972/3) that he had already been superseded and his time was done, the proof being a shabby little Dirty Harry imitation he made the following year, McQ. Kael—with a characteristic mix of heartiness and heartlessness—blasted it to smithereens. Eastwood, by his own account, never replied to Wayne’s letter.

(In a very curious side note, Wayne died of cancer a few years later, cancer which allegedly he contracted as a result of witnessing an atomic detonation while playing Genghis Khan in The Conqueror, in 1953. The name of the atom bomb, bizarrely, was “Dirty Harry.” Apparently the makers of Dirty Harry were referencing this bomb in their film. Wayne’s last film was The Shootist, about a gunfighter dying of cancer. It was directed by Dirty Harry’s Don Siegel.)

*

In her writing at least, Kael clearly disliked Westerns, not just the bad ones but the classics too. The only ones I can think of which she unequivocally praised were Peckinpah’s Ride the High Country and Robert Altman’s McCabe and Mrs. Miller (really an anti-western; apparently she loved Red River). In Going Steady, she dismissed The Good the Bad and the Ugly in a couple of paragraphs, as if not worth her trouble to write about. But in 1973, in “Killing Time,” she took a more nuanced stance. Spaghetti Westerns, she wrote:

Stripped the Western form of its cultural burden of morality. They discarded its civility along with its hypocrisy. In a sense they liberated the form: what the Western hero stood for was left out, and what he embodied (strength and gun power) was retained.

“In the figure of Clint Eastwood,” she added, “the Western morality play and the myth of the Westerner were split.” Kael linked the idea of a “liberation from morality” (and how she hated pious movies!) to the “fascist medievalism” of the Clint Eastwood-style anti-hero which came about when the Western myth was transposed to the modern urban milieu, via the police actioner. In her view, the liberation of the Western form, weirdly and in some tangly, spaghetti-like, roundabout way, led to the creation of “a nihilistic dream world.” This makes a certain sense if we consider that American values are all tied up with the imaginary vision of the West, and that nihilism is the absence of all values.

More fundamentally, nihilism relates to the absence of the father, God. It’s also the word Kael used (in When the Lights Go Down, “Notes on the Nihilist Poetry of Sam Peckinpah”) to describe another filmmaker who attempted to liberate the Western form from the cultural burden of Hollywood morality. In her own words, Sam Peckinpah was, of all contemporary American directors at that time, the one Kael felt “closest to.” (She meant it in personal terms—they were friends—but also in terms of responding to his work.) Though she didn’t review the film (due to her writing only six-months a year at The New Yorker), she called Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch “a beautiful, self-destroying machine”; while she was once again crowing about how the genre was dead, she wrote that “the new wine of The Wild Bunch explodes the bottle” of the Western.

There’s something here bubbling under the surface. It has to do with how Kael was looking for a movie hero (filmmaker/star) to “liberate” her from her “cultural burdens” by exploding the American dream world of the Western hero. This would have to do with her father projections, and go all the way back to her father’s “abandoning” her to escape into Studebakers, widows’ arms, and the fantasy world of Western movies. You think? It all adds up, even if it also all seems somehow… fantastic.

When Peckinpah made Straw Dogs, which was released a few weeks after Dirty Harry, Kael referred to the film in almost identical terms to those she used on Dirty Harry, calling it “a fascist work of art.” Peckinpah’s response (in Playboy) was that, much as he liked Kael, she was “full of shit”—exactly the same words Eastwood used. Whether this was a phrase Kael’s father used, it was almost certainly one she favored. (Peckinpah also used a more colorful phrase: Kael was “cracking walnuts with her ass”—presumably Sam’s imaginative way of calling her a ballbreaker.)

To bring it all into an even cozier, more incestuous perspective, Peckinpah and Eastwood—the two “male fascists” on whom Kael had set her sights—were slated to work together at exactly that time, with Jeremiah Johnson. The film was eventually made by Sydney Pollock and Robert Redford, and of course Kael slammed it. It was a Western, after all.

Unforgiven Men

Unlike Clint’s movie characters, Kael (born and raised in the West) never wore cowboy boots—she was only accused of it because of her writing style. As if to compensate for her diminutive size and soft high voice, her prose had a noticeably masculine flavor: bawdy, sexual, frank, aggressive, and (unlike Eastwood, well-known for his laconic, instinctive, anti-intellectual personality) intellectually super-potent. Kael’s independence and freethinking nature would also have been what made her both a threat and a challenge to movie studs like Eastwood and Warren Beatty, for whom, one imagines, women were to be treated like horses, subservient creatures to be harnessed, ridden, and trained to come when whistled (and to eat obediently out of their hands)…?

When Eastwood made Unforgiven in 1992, the film elevated him from a mere movie star icon to a film artist legend. Unforgiven was superficially presented, and received, as a kind of apologia for Clint’s previous track record of violence-avocation. And while it’s true he hasn’t done anything overtly pro-violence since that film (even Gran Torino had him martyr himself), it’s questionable just how convincing a case against violence Unforgiven really made. The film is vocally against violence—courtesy of Eastwood’s self-castigating, philosophical musings in the film—but scratch the celluloid surface and underneath lurks the same Western myth of “man with violent past coming to the aid of helpless villagers” (in this case prostitutes), using violence to save the community. As I wrote in 1999, “Unforgiven is more complicated than deep—its complexity comes not from a conscious ambiguity so much as a kind of schizophrenia that exists between its intentions and its methods.” Presumably this schizophrenia—or dividedness—exists in Eastwood himself.

If with Unforgiven Eastwood was genuinely trying to make a new start, somehow he couldn’t quite do it. The fact he even tried to, however, makes me wonder if Kael’s protests didn’t get through to him at some level. Maybe at least part of the reason Eastwood was so “haunted” by her calling him a fascist medievalist was that, deep down, he knew she was right? Kael got his attention, and she held it as long as it took for the penny to finally drop. Not all women were only looking to get fucked. Maybe this accounts for his continued anger and disappointment when Kael didn’t receive William Munny’s attempt at “repentance,” and she continued to badmouth him even post-Unforgiven? (Except for the bit about his sexiness.) Unforgiven indeed.

*

Curiously, Pauline Kael used the word “stoned” in reference both to myself and Clint: in “Killing Time” she called Eastwood “the first truly stoned hero in the history of movies.” Twenty-five years later, in her generous response to The Blood Poets, she referred to my sensibility as “only slightly stoned.” Naturally this caused me to question exactly what Kael meant by “stoned.”

One obvious meaning is being “out of it,” out of touch with reality, dissociated. This fits with Kael’s description of Eastwood as being somehow disembodied. (“There’s an odd disparity between his deliberate, rather graceful physical movements and his practically timberless voice. Only his hands seem fully alive.”) Kael saw Eastwood as lost in a narcotized, “nihilistic [Godless] dream world” of his own creation—a kind of movie trance state. Eastwood may even have acknowledged this, in an oblique way, when in Unforgiven William Munny admits that the only reason he was so dangerous was because he’d been half drunk the whole time: his “stoned” state slowed down his movements and allowed him to keep his cool, while the other guy panicked and fired off shots blind.

Kael was probably the only movie critic to equate Clint’s coolness with being stoned, or dissociated. Eastwood’s movie characters are usually associated with autonomy (even to the point of rebelliousness), individualism, uncompromising integrity, and ruthlessness. His public persona is also associated with these qualities, as well as with phenomenal worldly success and high social status (and latterly, artistic integrity). All of these are superficially masculine qualities. Yet throughout his career—up to and including his breakthrough “artistic” film Unforgiven—violence, and the implicit or explicit glorification of male brutality—has been the predominant ingredient. This was Kael’s main “truck” with Clint.

If, as Slavoj Zizek and others have argued, violence is a show not of strength but of weakness, then maybe something similar can be asked about Eastwood’s apparent creative independence and achievements as a film artist? How much has his stonedness, say, allowed him to be used as a celebrity-tool for parapolitical agendas, and how much has that usefulness been instrumental in his success as an actor and a filmmaker? If Eastwood’s output implicitly reveals a lack of authentic autonomy, it would have been this, and his “truly stoned” quality that allowed it, that Kael was reacting so violently against.

Her rejection of Eastwood as a suitable role model for the young would have been fired not only by this awareness but, less consciously, by her own experience of being let down and deceived by such a man. Was it this (and not just Eastwood), that Kael was implicitly, and of course indirectly, warning me against? Eastwood seemed to have all the desired qualities, both in his film roles and in his life, of a manly (fully embodied) sort of man, and maybe that was what Kael saw in him at first—his spaghetti sexiness. If so, she quickly changed her view of him, and with such ferocity that there was almost certainly something personal—some feeling of betrayal or at least disappointment?—behind it.

Kael’s identification of the corruption of the art form centered around the movie star as a western hero; her implication was that it wasn’t just that playing western heroes made an actor a movie star, but that, by playing the western hero, movie stars kept the western ideal alive. It was a two-way trade and it was 100% illicit. It was a lie, because the idea of the western hero is completely at odds with the idea of a movie star. The western ideal is that of an independent man, unshackled or burdened by the constraints of civilization, unsocialized.

The movie stars who played these heroes were men of culture whose status, whose livelihood, required they be shackled to the social system. They were like kept horses, trained and saddled to be ridden, and the cowboys they played were equally saddle sore. It was the sneaky sleight of hand of capitalism in Hollywood microcosm: the movie ideals of masculinity and independence, by being associated with social status, wealth, and influence, were part of the implacable machinery which “civilized” the West, and by which the “heroes” (including Kael’s father) were emasculated, tamed, and “broken in.” The ideal of the free man was central to the ideology that enslaved all men.

*

Kael’s famous statement about how her film criticism was also her memoirs can be read two ways. It could indicate that Kael went so deeply into movies that she revealed everything worth knowing about herself. Or it could suggest that she kept such a tight lid on her private, inner life, that she lived so much for and through movies, that there wasn’t much else to know about her outside of her critical responses. In a way, the two statements are the same, but I think both are inaccurate, which is why I found Kellow’s biography so disappointing. Kellow took Kael at her word, and even then, he didn’t dig up many bones from the official burial ground of her “memoirs.”

My own view is more like this: following in her father’s wandering footsteps, movies were Kael’s “dream landscape.” Like so many of us, she buffered herself from the tawdry corruption of the real world by escaping into movies. As she grew older, she opposed the tawdriness of the movies themselves by approaching them critically, as a writer, hoping to somehow redeem them through her passion, her attention. If the movies captured her father’s attention so deeply that he went missing from her life, she would give the movies that same level of attention, the attention she had wanted—needed—for herself.

By writing about movies in the way she did, she imbued the act of moviegoing with an almost religious (definitely sexual) depth and meaning. By adding her own energy and attention to the light-stuff of phantasy, by attempting to rescue them from the tawdry corruption of men like Wayne and Eastwood—the “cowboy killers” she both scorned and unconsciously emulated—and looking to people like Peckinpah and Beatty as “rescuers,” she gave movies a third and fourth dimension. By adding the images taken from her own dream or interior life, she temporarily redeemed the landscape, and her own dreams into the bargain.

A longer and more autobiographical version of this essay first appeared in Seen & Not Seen: Confessions of a Movie Autist.

Jasun Horsley is an existential detective, cultural commentator, and author of several books, including The Secret Life of Movies, Seen & Not Seen, Dark Oasis, Prisoner of Infinity, and The Vice of Kings. He hosts a weekly podcast called The Liminalist, and runs a thrift store with his wife in Canada. His website is https://auticulture.com

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or click on the icon below:

Get Cinephilia & Beyond in your inbox by signing in

[newsletter]