December 6, 2015

By Sven Mikulec

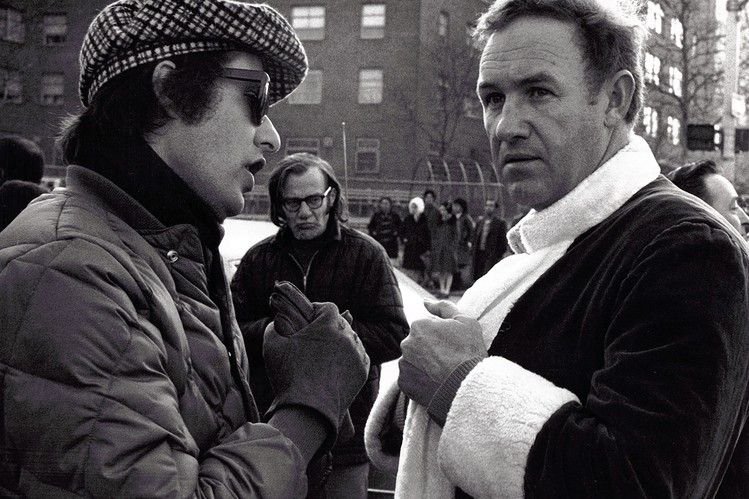

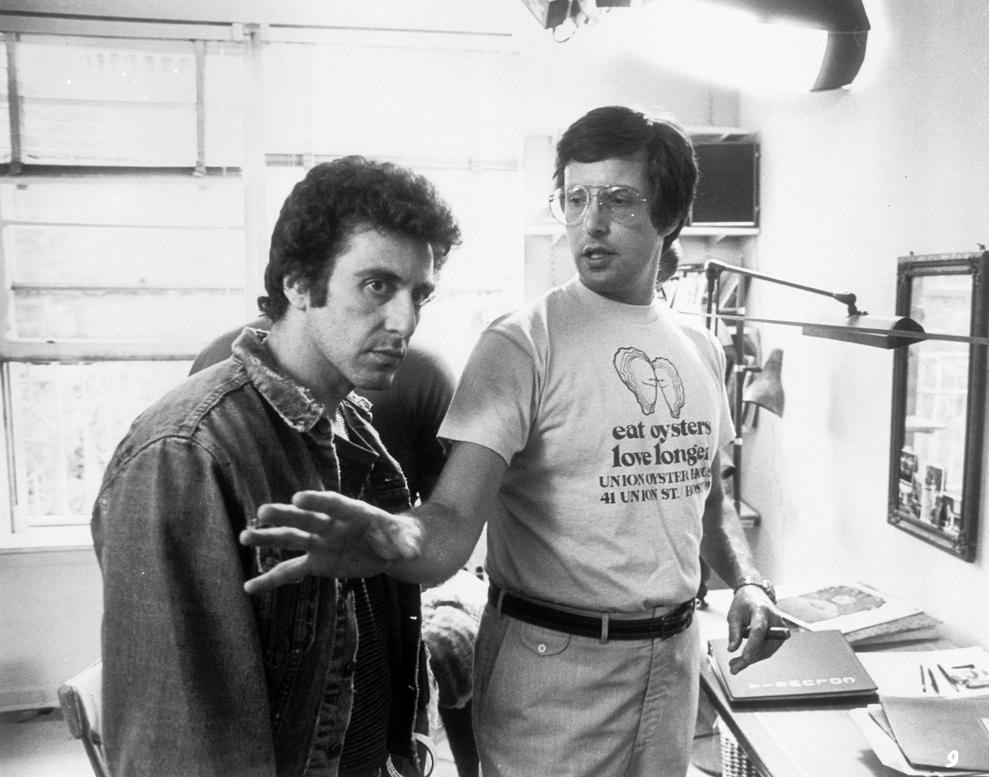

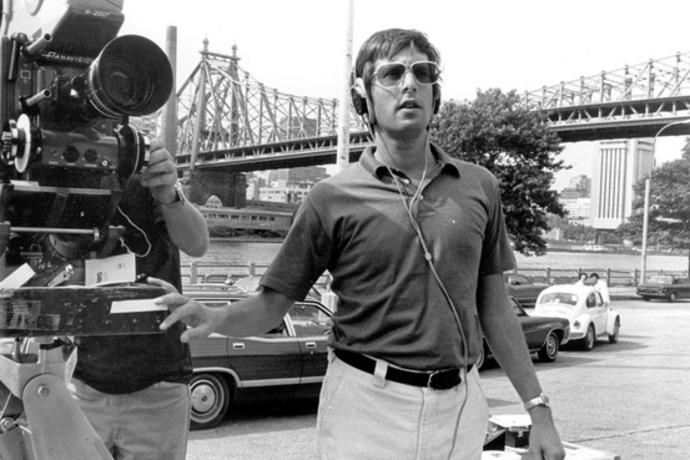

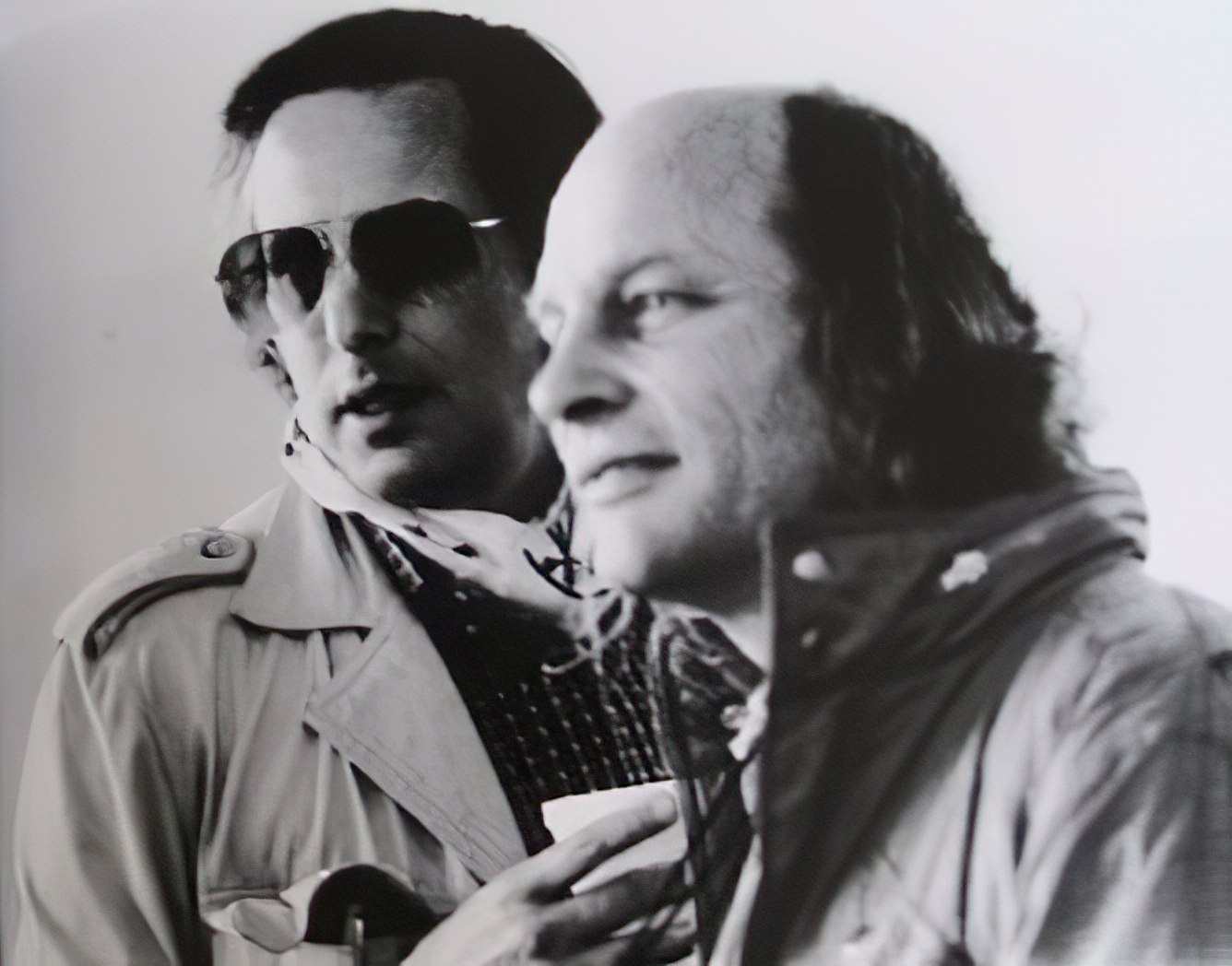

It was The Exorcist and The French Connection that put William Friedkin on the cinematic top of the world, but the attention-worthy films in this filmmaker’s dossier are too many to mention in this clumsy little introduction. When we found out Mr. Friedkin followed our website, we realized there was a solid chance of having a chat with him, which, we thought, would be the best possible award for the effort we put into building this little cinema haven in the endless chaotic jungle that is the Internet. Luckily for us, Mr. Friedkin proved to be a very friendly and open, albeit busy person, who agreed to (metaphorically) sit down with us for a while. With a desire to hear his thoughts on some of the landmark films he made over the years and the projects he currently has in store for filmlovers around the world, we embarked on this adventure without daring to suspect the conversation would stretch enough to discuss subjects like the contemporary degradation of art, the importance of film criticism and the position of women in the film industry. All I can say is, it’s been an honor and pleasure to pick the mind of one of the most significant filmmakers of the last half a century, and hopefully, the pleasure will not be mine alone.

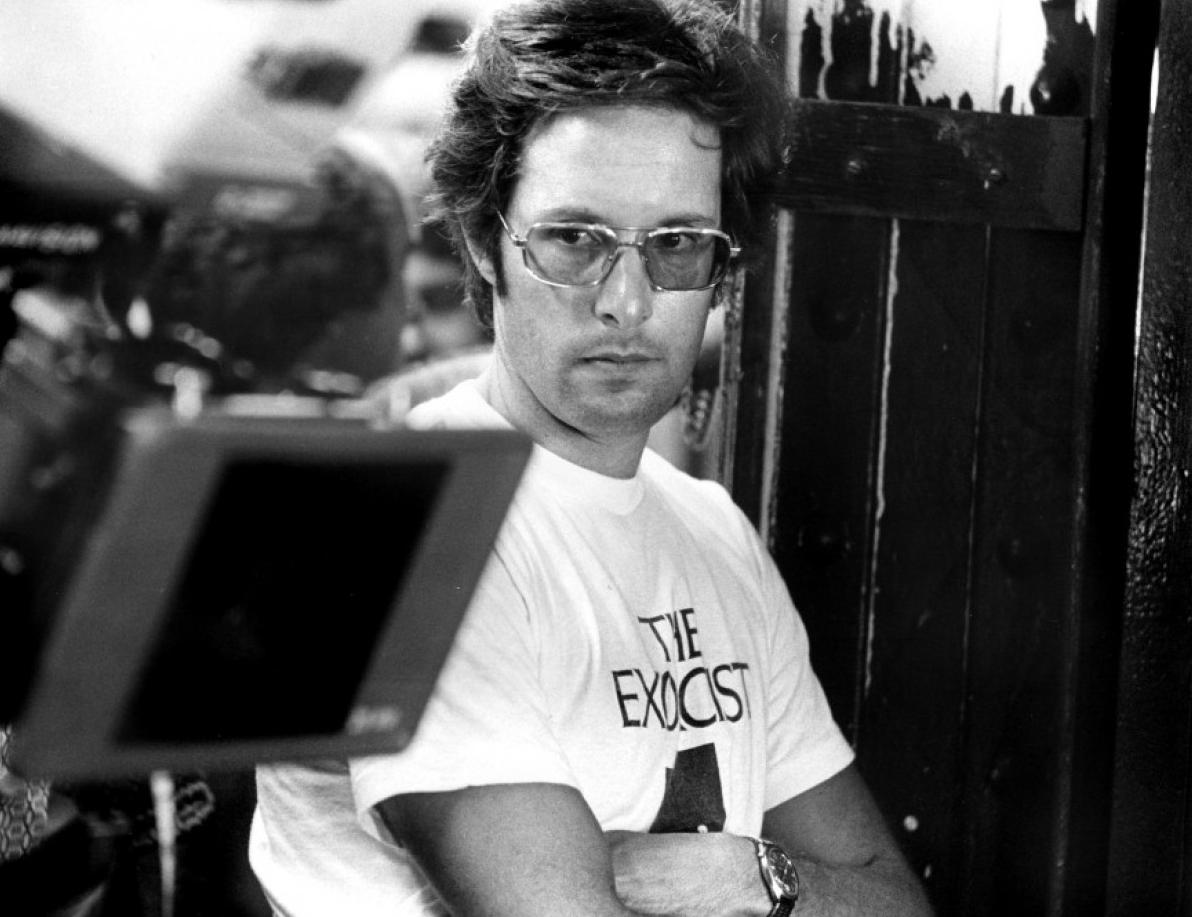

You stated a couple of times that, when you made The Exorcist, your intention was never to make a horror film. The fact that people consider it to be one of the best horror films ever made says quite a lot about how frightening exploring the nature of human beings really is.

Well, by now, obviously I recognize that audiences for generations have considered it a horror film. I won’t deny that, but when I set out to make it, the writer and I never had any concept of it as a horror film. We thought of it as a powerful, emotional, disturbing story. But we did not think of it in terms of a horror film, let alone a classic horror film, or a lot of the stuff that passes for horror films. We just both found this story, which was inspired by an actual case, you know, to be very powerful, and I thought would be cinematic. But I never thought in terms of horror films, like the ones that I appreciated, like Psycho and Diabolique, and Onibaba, and a handful of others. They are clearly horror films, and I didn’t think of The Exorcist to be one of them when I made it. Now I understand that the public thinks of it that way, so I don’t dispute it.

And what do you think scares the public the most?

Well, why bad things happen to good people. An innocent 12-year-old girl, who goes through extraordinary symptoms that clearly represent a disease that medical science is unable to deal with. That’s extremely disturbing to people. Because most people either have a child, or have been a child or are a child. So whenever your child goes through the sort of illnesses that are depicted in The Exorcist, it’s of great concern to everyone. And I think the fact that I made the film in a realistic way is what ultimately gets to people. It’s not done as though it takes place on a planet far, far away or something like that, or in an intangible world—it’s set in the real world, with characters who are portrayed as humanly possible. So I think that the fact the story is portrayed realistically is what disturbs people about the events in it. It was a very productive and exciting period to work with William Peter Blatty on his great creation.

The characters in Sorcerer are forced to cooperate to save their asses, without fully trusting each other. They are thrown together in one hell of a mess, and getting out of it requires trust, faith and collaboration. Would you draw a parallel with the world today? Especially in the last couple of years?

Yes, it’s even more relevant today. But at the time I made the film, in 1977, I felt that way, the way you just described. That the world had come to a crossroads, where the major powers would all blow apart if we didn’t pull together. And I thought Sorcerer was a metaphor for that idea. I think it’s much, much more dangerous today. I think the world is on a precipice today. I don’t see any strong leadership to counteract the terrorism that exists in the world, as well as various other problems. I think if the world does not pull together, it will blow apart. And it has now affected innocent people sitting at an outdoor café somewhere, who have no politics, you know, no particular philosophy that would be disturbing to someone else. There is just evil in the world, and that’s what relates Sorcerer to The Exorcist. There is a force of evil in the world that causes all these problems. Life is actually a beautiful gift, but people regard it not as something that is vulnerable, but as something that they take for granted. The major powers in the world just keep threatening each other, attacking each other, and there’s going to come a point where there’s enough nuclear proliferation to destroy the world. So yes, that is the metaphor behind Sorcerer.

Back to a brighter topic, I was certainly glad to learn about your attitude towards contemporary streaming television like Netflix.

Oh yeah, there are much more interesting things being done, unfortunately, in streaming and on cable television than there are on movie screens. In this country, anyway, but in many other countries also. The whole idea of the art film, or experimental films, receiving an audience in theaters has virtually disappeared from the United States and so many other countries, except in fringe areas. And when I was growing up it was a staple of cinema.

You said that everything that Hollywood produces these days is just Star Wars, that the film completely shaped what we considered the American movies since it got out. How heavy is Star Wars’ responsibility for the current state of American filmmaking?

Well, it was hugely successful, beyond anyone’s wildest dreams. Including the filmmaker’s. There are occasionally films that present a complete change in the zeitgeist, and nothing more than Star Wars. It became the goal of every studio—to make another Star Wars, or a version of Star Wars. And then they started to analyze, well, what is Star Wars? Well, it’s kind of a comic book. So now, the mass production of films from the Hollywood studios are comic books. Batman, Superman, stories like The Hunger Games, so many, Iron Man… I’m not saying this in a negative way, this is what audiences want to see. Everywhere. These are the most popular films, and they very often crowd out other kinds of films. I imagine that’s true in Croatia, isn’t it?

It’s the same here, yes. But what makes television the suitable home of quality visual storytelling these days?

Cable television and the streaming services have to come up with an alternative to what people want to see in the cinema. And what they turned to, fortunately, for the most part—not totally, is well-written stories, with believable characters in situations that are both tense and dramatic and believable. Now, this is not true of all television certainly. But the kind of television that resonates with me are shows like 24, and Homeland, and X-Files, and The Sopranos, and many, many more example of things that could not be produced for the cinema in this country. And there’s great television that I’ve seen from other countries! Like Israel or Sweden, England and France. A lot of these films come over here now, and they come as television series. That’s why television represents an alternative to the basically mindless experience of going to a cinema today. With rare exceptions, though. There are exceptions—I can’t say there are no good films being made. There are, but they are of a far fewer variety and number than they were made, let’s say, over thirty years ago.

But there must be a good chance this superhero comic book assembly line will die out soon, the market must become saturated at some point.

I don’t see that. I don’t think it will die out, I think that’s the new zeitgeist. If it isn’t these particular films, it will be copies of them. It will be something else, that is completely unbelievable, and supernatural, and whatever. Just these fantasy comic books. That, I’m afraid, is the future of cinema. Until I see some change at least. When you say you think it’s going to die out—it doesn’t look to me as if it’s going to happen. This is what the audience has become conditioned to. And the audience in the United States is for superhero movies, which to me are almost completely mindless.

The small, independent movies today are the closest we can get to what was used to be made in the seventies.

Yes, but they are very marginal now. It was possible to get a much larger audience for serious cinema not only in the seventies, but long before that. I’m sorry it’s that way, but that is what people want to see in a cinema today. Because largely the people who go to the cinema are in a much younger age group. The largest number of moviegoers here are between the ages of 15 and 25. That’s what they want. Even college graduates, or serious people, want to see that.

But besides television, can you name a couple of films that you enjoyed over the last couple of years?

Well, I can tell you I have not enjoyed many. But I recently saw Creed, which is another version of Rocky. And I thought it was terrific, I thought it was really good. Well-written, well-acted, great story. They reinvented that genre. I thought it was sensational. I’m trying to think of any other films that I’ve seen at the cinema that I really enjoyed to the extent that I enjoy films from the past, and I can’t think of anything to compare to the films that I really love. But Creed was very good. And you probably know that I saw the little Australian horror film called The Babadook?

You wrote about it on Twitter, yes.

Well, I like that picture! It took me completely by surprise. That’s a little horror film, but I thought it was just beautifully made, very convincing and very disturbing.

What about other contemporary horror films?

Nothing! Nothing. Zero.

The box office results tailor the careers of all filmmakers, and yours was no exception. But it must feel great to see Sorcerer, Cruising and others get the recognition they deserved, even after all this time?

Look, I’m very happy when films that I’ve made are still recognized by whomever, decades after they were made. Of course I’m very happy about that. But for most part you make films for a contemporary audience. The reason I haven’t made more films since then is simply that I haven’t found anything that interests me enough. It’s not that I haven’t been looking, but I’m not just going to do any film that I have no real passion for simply to make a film, and then ask people to buy tickets to see it. If I don’t want to see it myself, I have no interest in making it.

And what attracted you to Don Winslow’s The Winter of Frankie Machine?

I think it’s a very interesting character, in an environment that I know and understand well. I like his writing. I like his work very much. I think he’s much more than a thriller writer. I think there’s a depth to his work and a kind of realism that comes from his own experiences in life. He was a private investigator at one time, you know? It’s rooted in reality. It’s a character I think that I understand. It will have to be very well-cast. The ideal actor would’ve been Paul Newman, but unfortunately he’s not available now. But when we get the script, you know, it’s something that I would give to Matthew McConaughey.

One close-up of Steve McQueen is worth far more than the photograph of the most beautiful landscape in the world. Your quote. There are no studio stars today like it was in the past, but taking charisma, talent and charm into consideration, who would you say could fill the shoes of actors like McQueen or Newman?

Nobody. And not only those American actors, but also people like Lino Ventura, and Jean Gabin, and Marcello Mastroianni, and so many others. So many others from past generations who represented a kind of movie magic. And many women, as well. I don’t think there are any women anywhere near as interesting as the female stars of the past. And certainly there’s no Orson Welles around. God knows I could name so many actors, not just movie stars, but actors whose light doesn’t exist anymore in the English speaking world. You know, Alec Guiness, and Peter Sellers, you could go on and on, it would just be name recitation. But for example, everything I’ve seen that Humphrey Bogart did was interesting in and of itself. Actors like Peter Lorre when he worked in Germany, and did things like M for Fritz Lang. We don’t have actors and actresses like that anymore.

On occasion you see some obviously good performances. I watch basically the same films over and over again, like reading a novel again, or listening to a piece of music again. I never tire of listening to the Fifth symphony of Beethoven conducted by Carlos Kleiber. It’s a masterpiece from which I get something new, some new detail, every time I listen to it. Or the Ravel string quartet in F. And God knows, if there was anywhere else that I wished to live, it would be in the Netherlands, across the street from the Rijksmuseum, where I could walk in every day and see a Vermeer or a Rembrandt. And that’s not easy to do where I live (in Los Angeles). If I lived in New York, I could walk into the Metropolitan Museum and see about five Vermeers and more than a dozen Rembrandts. But nobody paints like that either today! I see a diminishing of all the art forms. Are you gonna tell me that painting has moved upward since the times of Rembrandt and Vermeer, and the 17th century? Has painting advanced today in terms of craftsmanship and interest of the viewing public? I really don’t think so. I just don’t think so. And the same thing is with cinema, and the same thing is with music. Who writes music like Beethoven? Or Bartok? Who plays jazz like Miles Davis? Who is as good of a popular music singer as Frank Sinatra? And when I give you these honest answers about my feelings about art, I sound like somebody who’s stuck in the past. But I’m really not, I am looking to be inspired by the work of today. I don’t see it in a museum, I don’t hear it in a concert hall, and I certainly don’t see it in cinema.

So you’re saying there’s a tragic situation since with the rise of technology art can be presented in the best possible way, but there’s a constant diminishing of the quality of artists?

I think so, but that’s just my opinion. Yes, the technology affords you the opportunity to create almost anything, and to create it in three dimensions, or in a widescreen… There are certainly more ways to paint and ways to compose music than there ever were. And there’s a larger audience available. You know, Beethoven basically composed music in the 19th century for Europeans. And yet these works live on. I don’t know how many musical works are going to live on into the future, I certainly can’t predict that, but there’s not a lot that has caught my attention. And I’m not complaining! These are just facts. I’m always hoping and looking for something that will inspire me. Well, like the film The Babadook, which was completely unexpected, or this film Creed, which is a kind of reinvention of Rocky, which is now 40 years old. It’s a damn fine picture, very well-made, with wonderful acting. It’s the best thing Stallone has done since he did the first Rocky.

I’m still waiting for the film to come to Croatia.

I’m sure you’ll get it, and boy, did it take me by surprise! Because I try to see a lot of things, I try to watch as much as I can. There are some things I’m not attracted to, but there are a lot of films I do want to see, and very often I’m just disappointed. But I listen to new music, and I look at new artwork, and I look at new plays. In America, there are a lot more interesting things happening on stage than there are in cinema. There are certainly not many works that are in the category of what was done by Arthur Miller, Tennessee Williams, William Inge, Clifford Odets and others. But Tracy Letts, who wrote Bug and Killer Joe, is a playwright who I would put in that category, with someone like Edward Albee.

You said it’s easy for you to work with Tracy Letts, since you share the same worldview.

We have a vision and a view of people and society that is rather similar. Neither one of us is particularly political, which is an odd thing to say to someone from Croatia, where politics is vital. But right now in the United States of America I don’t feel that politics is series or vital. I don’t think a lot of people are really paying attention or give a damn who gets elected to the highest or lowest offices in the land. And unfortunately, because of the press, the best and the brightest people don’t want to run for political office, because the media would immediately pounce on them and find any number of things that suggest that they are unfit for office. There’s not a lot of people that would want to go through that. This wasn’t the case many long years ago, when you had some of the best people in society running for political office. Unlike your part of the world, we don’t come from a place where there have been dictatorships. The progress, for example, that the United States made during the Civil War is amazing. Forget the Revolutionary War, when the US broke away from England. But the Civil War was run by a bunch of guys wearing big, heavy, woolen suits and military uniforms, they were smoking tobacco, smoking cigars in small, un-airconditioned rooms, drinking whisky straight from the bottle. And these guys were making decisions about things that reverberate to this day in our country, like civil rights, for example. And they fought and died for civil rights. 750,000 people died in the American Civil War during those five years. The guys who made this happen were almost backward in their knowledge and intelligence, but what they had was a passion and a fire, a belief and faith that I just don’t see today. Today we’ve got a bunch of well-dressed guys in two thousand dollar suits and beautiful ties eating off the finest china and drinking the best wines, and they are gentlemen, they sit around rooms and discuss things for which there is no solution.

Since you mention civil rights and how the society changed over time, I want to ask you about the position of women in the film industry. There has been a lot of talk about the inferior position of women filmmakers. What are your five cents?

Well, I’ll give you my thoughts on that. I’ve been in Hollywood for fifty years and I have never met an executive of a television or movie company, or a talent agency, that was prejudiced against people of different colors or against women. I’ve never met anyone. Now, why there are more men directing films than women, I can’t answer that. But it’s not because of prejudice. I think the very best director of action and other films is a woman named Kathryn Bigelow. She’s a great filmmaker, period. It’s a question like why there are more white basketball or football players in America. Most of them are black, or from another country. Why is that? The only answer to that is that they compete and that they’re better! Wherever women can compete, they get the jobs. I don’t know anyone who’s prejudiced against African-Americans or women, I’ve just never seen it. Why is that there are more black athletes? Because they’re better. So what should we do? Should we get some legislation or pass some rules that there have to be more white players? No, you can’t do that! Why are the greatest painters that ever lived mostly white men? I don’t know! Women are free to paint. But you cannot pass diversity laws in an art form.

If you could choose to do an exhibition of Vincent van Gogh or a woman painter from the same period, what are you going to choose? Why is that, I don’t know. I’m not a woman, or an African-American, so I can’t speak to that experience except to say that I know it’s an open playing field. And today there are many, many women in the entertainment business here who are in charge of everything. You know, my wife was the head of a studio thirty years ago, and ten years ago she ran two studios. Why? Not because she was a woman, but because of merit. When somebody auditions for an open chair in a symphony orchestra, they audition behind a screen for the general manager of the orchestra or for the conductor. The manager or conductor don’t know if they are a man or a woman, or what color they are—they just play behind the screen the pieces they’ve prepared, they don’t talk. So today, for example, if you go to a concert by the Los Angeles Philharmonic, you see a great many Asian women in the orchestra. The growing number of people in a symphony orchestra around the world are women, and in fact they are Asian women. I can’t explain why that is, but that is an open playing field, and I believe that cinema is too. I have never heard of a man running a studio, talent agency or a network saying, oh, I don’t want to hire a woman for that job. But women have to put themselves forward. I mean, just today, or yesterday, a law was passed in America saying that women will now be present in all areas of combat in the military. There will be women on the battlefield, if there is one, equal to men. So that, among many other things, means there has been progress for women. All I can say is that I’m certain people have faced obstacles in trying to work in all the art forms or in sports. I was a pretty good basketball player when I was a kid in high school, but I could never play on a professional basketball team. There was no way anybody could pass a diversity law so that I could. I just wasn’t good enough. And that’s hard for people to face. If you’re good enough, you’re gonna work. All this other stuff to me is just smoke screen.

The fellow who directed the movie Creed and was one of the writers is a young African-American man. He’s talented, he’s made only two feature films, he’s basically recently out of college. But he’s got the talent, and nobody gives a flying fuck what color he is. I had people work on my films who are African-American, who are women, and not because they are African-American or women, but based on what I thought was their merit. I don’t know anyone that wouldn’t do that. Anyone who would do that, anyone who would deny a talented woman, or a talented member of a racial minority, a job, is just an asshole, and not fit to be in a position to hire. Are there assholes in every business in every industry, in every country? You bet. But that doesn’t mean it’s going to be cured by some kind of diversity rule.

Meryl Streep recently stood out and warned that female film critics are extremely inferior in number to their male colleagues.

Oh, fuck that! Jesus H Christ! I can’t even comment on that stuff. She is a very successful actress who works all the time and can work whenever she wants. Unfortunately, not every member of her gender is as talented as she is. And that’s all you can say about it. And who the fuck is counting the gender of critics?! What is that? Are we now asking for diversity among film critics? Oh my God! What is the world coming to? Let me just say this to you. I guess in the United States, which is all I can speak about, I think there are probably now more women than men. So the whole concept about how many women will be critics or directors or whatever is bound to change. In terms of African-Americans, there are fewer African-Americans in this country than white people, and as their numbers grow, there are bound to be more African-Americans in all facets of the art. Just by sheer numbers.

What do you believe is the importance of film criticism today and how would you compare it to what was being written decades ago?

Let me just say this. And let’s just stick to film for the moment. There are many more good film critics today because of the Internet. I’ve seen reviews or appreciation of films—a lot of them on your site! And many other sites. There’s a proliferation of interesting writing about cinema that I’ve seen in recent years since the Internet. I wish there were better films to warrant this growth of film criticism. And there are far more film critics who are knowledgeable today about cinema because of the dissemination of information about all kinds of cinema, including classic cinema. There are far more, and more interesting critics than I can recall when I started. There are also idiots writing about film, there are idiots making films. You know, it’s the usual number.

I think right now the mainstream critics in this country go out of their way to praise some of the films that are made and that don’t compare at all with the classics of the past. But as a film critic, you’re just exercising your opinion. There’s nothing finite about it. A review from the New York Times is no more actually important in terms of its overall impact than a review from you name it. Rotten Tomatoes or Cinephilia and Beyond. They simply represent the opinion of the writers.

Do you read reviews of your films?

Yes, I do. I mean, not all of them certainly. I generally read what gets sent to me or comes to my attention. Good or bad. And I’ve read a lot of negative reviews on occasion that I find interesting, if not insightful. And I’ve read a lot of positive reviews that are just, you know, not that helpful. But there are very good writers writing about cinema today. All over the world. I didn’t realize you, for example, were in Croatia. So there you go. You’re writing about cinema thousands of miles away. You write essays. You write long think pieces about films. And that, in essence, is a review. It’s not likely, is it, that you would write a long piece about a film you hated? What is the point? Why waste your time or the characters on an iPad, or a computer, or an iPhone, or whatever the hell you’re writing on. Why waste your time if you don’t like the film?

Writing about films is as varied as making them. There are good films made, and there are bad films made. There are good pieces about films, and then there’s unintelligent stuff. To me, the motivation and purpose of a reviewer should largely be to try to get people to see the film. There’s a guy who writes in the Wall Street Journal, and some of his reviews are so negative and so personal that they are worthless to me. Whenever I see somebody write very personal attacks on the works of filmmakers I just wonder what the purpose of that really is. And the conclusion I’ve come to is a kind of, well, jealousy, of somebody who wishes they were doing it themselves. And aren’t, because they can’t. But then there are other reviews that you would have to say make you want to participate in cinema. If I was writing a film review, I would only review those films that I felt had merit. For me, the purpose of film criticism is to interest people in the art of cinema. What good is it to criticize a film that you absolutely don’t relate to, that you hate and that you want to attack? Very often those films are beyond the reach of the critic. I mean, somebody can write the worst imaginable crap about Star Wars, and it’s not going to affect the audience at all.

So writing horrible reviews is a waste of space and time that could have been used to turn the spotlight on a film that deserves attention?

My point exactly. Why waste the space? Why would I have to sit and read a piece about a film that the reviewer loathes? No, that I don’t do, that is a complete waste of time. The reviewer’s time and my own.

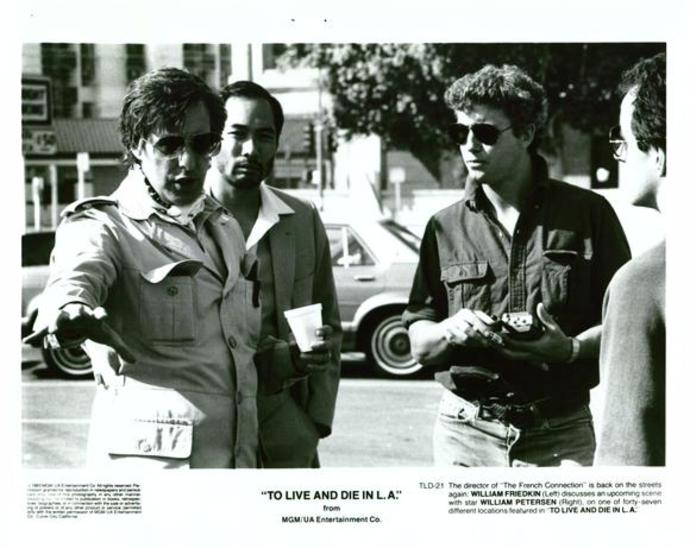

To Live and Die in L.A. is coming to TV soon. At what phase is the project?

We’ve just finished the first script. The script is written by a guy called Bobby Moresco, who wrote the movie Crash, won the Academy Award, and he wrote Million Dollar Baby.

Are you happy with the script?

Oh, very much. I love the script. My opinion is that it’s one of the best scripts I’ve ever read.

You’ll be directing the episodes?

I plan to, but I’ve already asked a couple of friends of mine to direct a few of the episodes, like Walter Hill. I’m gonna ask Nic Refn to do one, maybe a couple of other guys. Not that I don’t want to do them all, but these are friends of mine whose work I respect and I’d love to see what they would do with this material. There will be ten one-hour episodes.

Are you looking forward to returning to TV?

Well, I wouldn’t call it returning to TV, I’ve done TV periodically throughout my career, not a lot though. But the kind of television that I did before I did cinema was live television—variety shows, dramatic shows, sports, all kinds of things. But not dramas for television. I mean, I did direct a Hitchcock Hour, which, in my opinion, is terrible. That was the first thing I did on a sound stage, one of the last Alfred Hitchcock Hours made, and I don’t think it’s very good.

But regarding the stuff you think is good from your filmography, you explained you were never bother by box office results, but that you valued your films according to how close they came to your original vision of them. Based on this criterion, which of your films do you consider most successful?

Well, a few. I’m very happy with Jade, Rules of Engagement, Killer Joe, Bug, The Exorcist… I would have to say Sorcerer, and The French Connection. Those come immediately to mind. And To Live and Die in L.A. And it’s not that I achieved them, or realized them perfectly, but I did come very close to my vision of them in the execution.

Mr. Friedkin, it’s been a real pleasure to talk to you.

I think your site is great and I was very happy to do the interview.

An interview conducted by Sven Mikulec. Photo credit: Josh Weiner; Owen Roizman; Tony Friedkin; Jane O’Neal; Sam Emerson & Skip Bolen. All original photographs are copyright to their respective owners.

If you find Cinephilia & Beyond useful and inspiring, please consider making a small donation. Your generosity preserves film knowledge for future generations. To donate, please visit our donation page, or donate directly below: